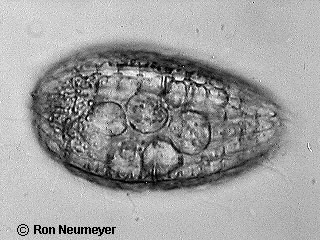

(Image right shows Coleps).

On return the catch must be looked at fairly quickly as some protozoa will only remain alive for a few hours, though this is helped if the bottle is kept cool, especially out of direct sunlight. If left overnight, many of the more fragile species will have died, but others will have accumulated on the bottom, where they are easily sucked up with a teat pipette.

A large volume of an unconcentrated sample is often easily concentrated by centrifugation. A hand-operated centrifuge (see Note 1) is very useful and is easily made from one of those battery operated mini-fans that are available each summer. A couple of plastic centrifuge tubes are fixed to the rotor blades. An alternative is to sieve the sample through a fine nylon mesh.

Protozoa are also abundant in mosses, particularly Sphagnum moss. A small sample of moss can be squeezed into a sample bottle, and this liquor should yield both testate and naked amoebae and some of the larger flagellates.

It is always best to observe undisturbed material for as long as possible. Free-swimming types are most easily observed on glass slides with cover slips supported by blobs of Vaseline at each corner. Cavity slides can also be used, though the greater volume of water can be troublesome. Excessive movement of the organisms can be slowed by using a viscous substance such as methyl cellulose, a drop being added to the slide (see Note 2).

Begin observations at low powers first, making observations and drawings as required, before moving on to higher powers. Both dark-field and phase contrast illumination techniques are useful if you have them available. One useful technique is to make a hanging drop preparation whereby the sample is put onto the cover-slip and then the cover-slip placed on the slide upside-down. As living cells become attached to the underside of the cover-slip they can be viewed with a high-power objective.

Paramecium

Identifying to species level is very time-consuming. However, it is often quite easy to place organisms into one of the higher levels of classification, and this is a more feasible thing to aim for when beginning study. As experience is gained and familiarity with the keys, identification to the level of genus can be reached.

1) A Micscape article describing simple hand centrifuges, their use and construction is planned in the next few months. Return to article.

2) Methylcellulose or an equivalent can often be obtained from laboratory suppliers especially for this purpose. In the UK it is sold by Northern Biological Supplies as 'Solution for protozoa movement studies'. Return to article.

The Micscape Library has built up a number of articles describing common types of protozoa, which we have compiled below. They are a fascinating and varied group for the amateur to study, as we hope our articles show.

Paramecium - one of the largest and easiest to find. A descriptive article with a superb image and annotated diagram.

Stentor - this large protozoan is also easy to find and looks like a trumpet, as this illustrated article shows.

Coleps - a 'comical beastie' but it's the armoured tank of the protozoan world and a voracious feeder.

Coleps - This unique image sequence, entitled 'The Good, the Bad and the Ugly', shows how nasty this 'beastie' can be. It describes Coleps and Urotrichia eating a rotifer egg.

Didinium - this 'master eater' isn't afraid to attack and eat Paramecium larger than itself, as this image sequence and article shows.

Vorticella - the attractive 'bell animalcules' with contractile stalks.

Podophyra - this 'remarkable ciliate' has hollow suctorial tentacles, the 'octopus' perhaps of the protozoan world?

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK