For the naturalist keen to explore on the macro and microscopic level the fauna and around them, insects can provide a wealth of studies for a lifetime. In the past few decades my brother Ian and I have noticed an alarming decrease in both the variety and population of insects local to us that were previously common—beetles, butterflies, larger moths, bees and other flying insects. For this reason I'm very reluctant to kill any insect found just to study—but there is no reason to because there are invariably a variety of insect casualties found throughout the year, whether indoors such as on windowsills or outside.

The Petri dish shown below contains the variety of insects found pending study, these include lacewings, bees, wasps, small house moths and flies. I was on a recent urban walk when a flash of red caught my eye on the tarmacked footpath—a dead red admiral butterfly. Microscopists are easily pleased and this made my walk and brought it home. Although very tatty and no doubt desiccated there will still be a wealth of features to study where cosmetic issues are not important on the macro and micro scale. Finding a dead butterfly was sufficiently unusual to promote it to the top of my list to study, partly because I have an interest in insect scales and their past use as test subjects for microscope optics.

The red admiral is a striking butterfly, one our largest, and unlike some of 'the little brown jobs' is not mistaken for any other species. In the past we have seen it regularly but in recent years only a handful of sightings locally. Our go-to book on British butterflies is The Butterflies of Britain and Ireland with informative, engaging text by Dr. Jeremy Thomas and stunning colour paintings by the natural history artist Richard Lewington (publisher Dorling Kindersley 1991). The entry for the red admiral notes that it is not native to Britain but migrates to Britain from central Europe in spring and summer to breed. It always amazes me how such seemingly delicate insects have enough energy to make long journeys.

The macro shots with larger fields of view below were taken using an Olympus TG-5 compact camera. I bought this a few years ago and find its built-in five image stack with its super macro 'Microscope' function very useful for folk like me who have little patience to manually stack. It has a 30 image focus through function for external stacking but have not tried that mode. The LED clip-on ringlight accessory was used.

A collection of Nature's casualties waiting to be studied. The Olympus Tough TG-5 shown with the LED ringlight fitted which can work at very close working distances. An optional ring flash accessory also shown which distributes the built-in flash, two intensity settings can be selected with a lever. The TG-x series is popular with underwater photographers as it's waterproof to 15m and has camera settings to correct for those lighting conditions. Its weakness is the small sensor 1/2.3" (6.17 x 4.55 mm) often used with super macro cameras for the matched optics to achieve such close working distances. Its noise performance above the base ISO 100 reflects this.

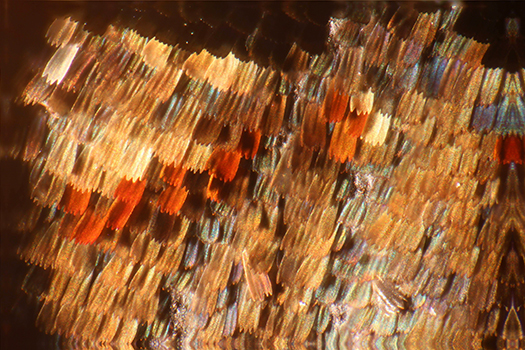

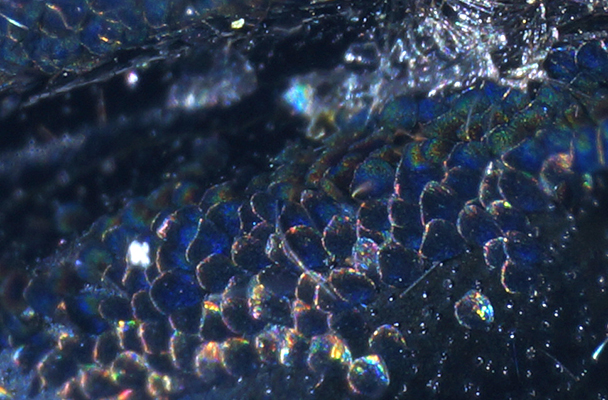

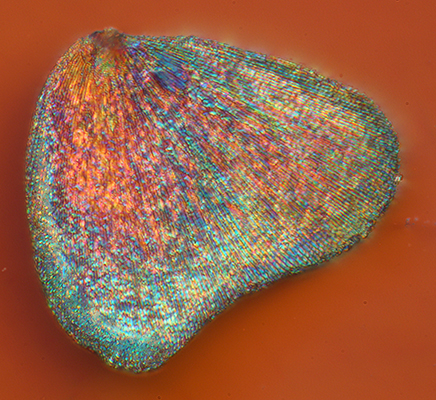

The wing scales both on the upper and underside of a pair of wings are always of interest and how their shape, size and colour vary to build up the patterns and colours. The patterns are built up by scales of varying colour and not by the physical structure of the scales reflecting light as found in iridescent butterflies such as the striking blue Morpho species of S. America.

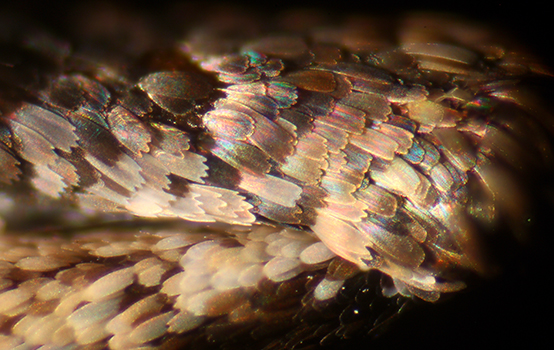

The upper wings use primarily solid blocks of the same coloured scales to build up the pattern. Underside at the macro scale there is a more subtle range of coloured scales some of which are somewhat iridescent.

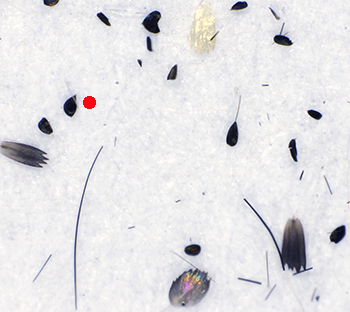

The tiny body scales remarked on below has an example marked with red spot compared with the variety of wing scales shown.

While studying the underside of the dark black body—now desiccated, under the low power stereo, I was intrigued by some black scales that were noticeably smaller than the typical wing scales. Transferring some with a brush to a microscope slide they were completely opaque under the transmitted light, even with near infrared which can sometimes penetrate dark insect exoskeletons. I rarely use the on-axis incident light accessory on my Zeiss Photomicroscope III as find on-axis light invariably flat. The scales looked reflective on the body so worth a try. The righthand image used DIC with the Zeiss 40/0.85 epi objective. A ca. 20 image stack using Alan Hadley's CombineZP freeware. I'm a beginner at stacking and learning the best stacking protocols so some stacking artefacts present. The scale is 87 µm wide.

The proboscis, palps and hairy compound eyes can be explored.

Underside of the head.

Intrigued why the legs and antennae have scales in addition to the wings, do they serve a purpose?

A close up of scales on the joint of the leg shown above.

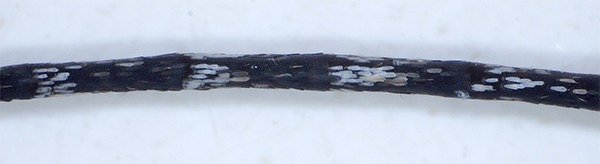

The white banding on the antennae on closer inspection are clusters of white scales.

Two of the palps.

Comments to the author David Walker are welcomed.