|

Another Look at 19th Century Slides or Old Slides Part 2 by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Old Slides Part 1, March 2023 issue.

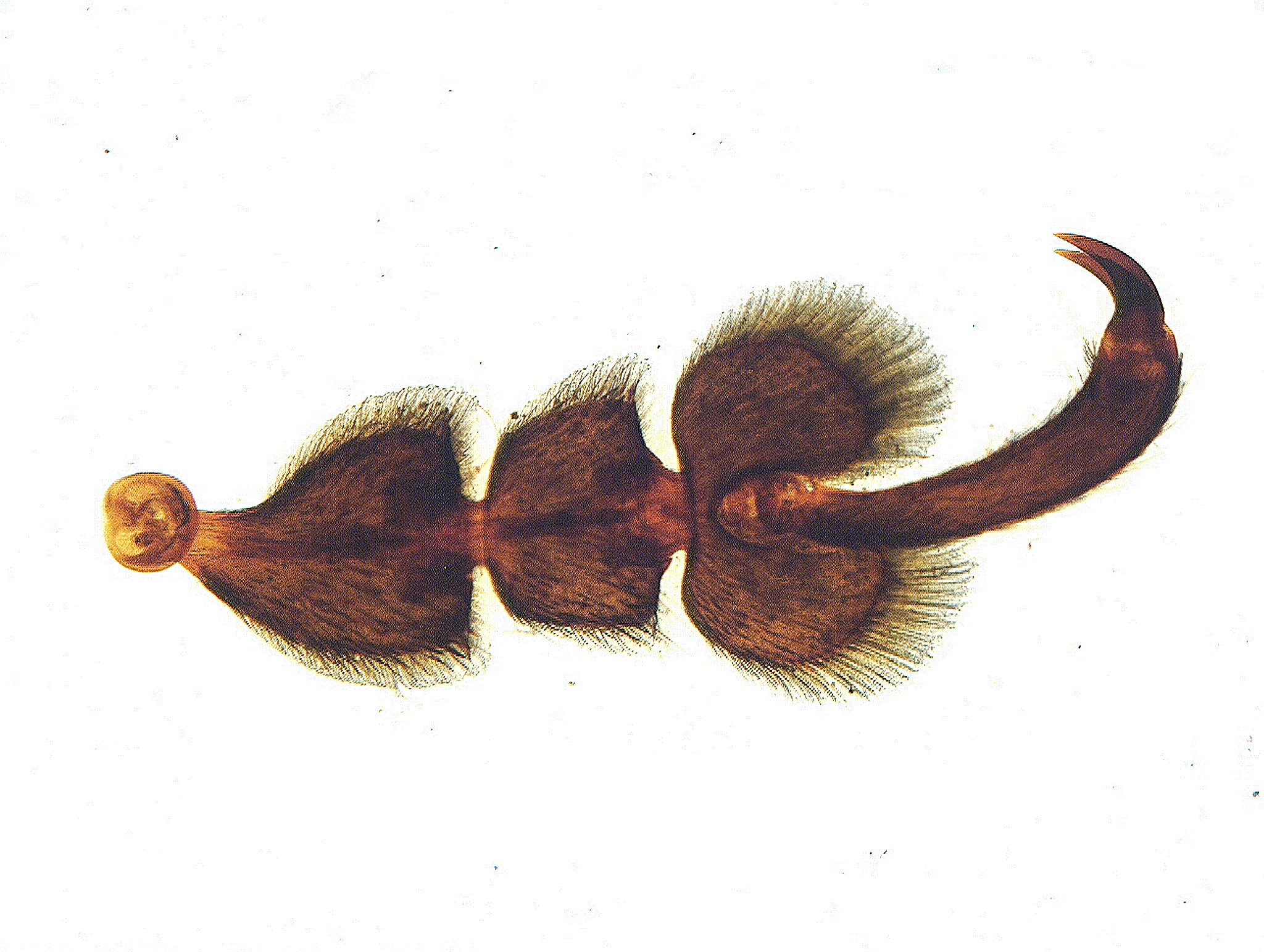

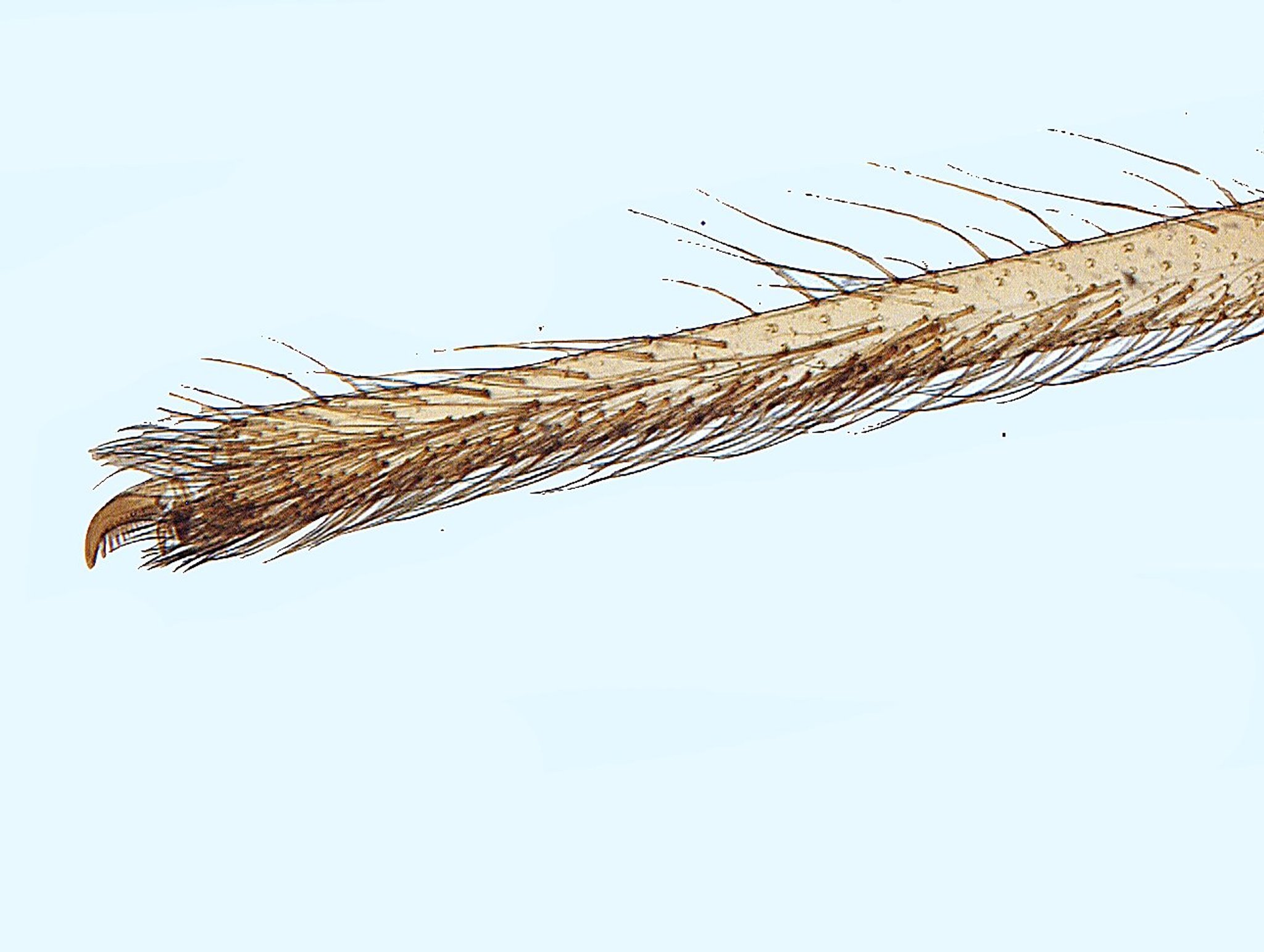

Let’s begin with a rather impressive specimen, namely, the foot of a diamond beetle. I’ll show you two views; first brightfield and then oblique. Notice in the second that the hairs are more distinct.

However, before we get too sanguine, let me show you three slides where the damage is so bad that no usable image of the specimen is possible. The first slide is labeled “Antheridia” which are found primarily in ferns and bryophytes. These are reproductive structures. As you can see, nothing of interest is salvageable here.

The next slide is of an ivy cross section. One can see the round section, but any further detail has been lost.

Next, again, a badly damaged slide. There is a printed label that states: “Medal Award”. However, the handwritten label that describes the specimen is not decipherable. So, here’s something that at one time was a distinguished something, that is now only worth discarding.

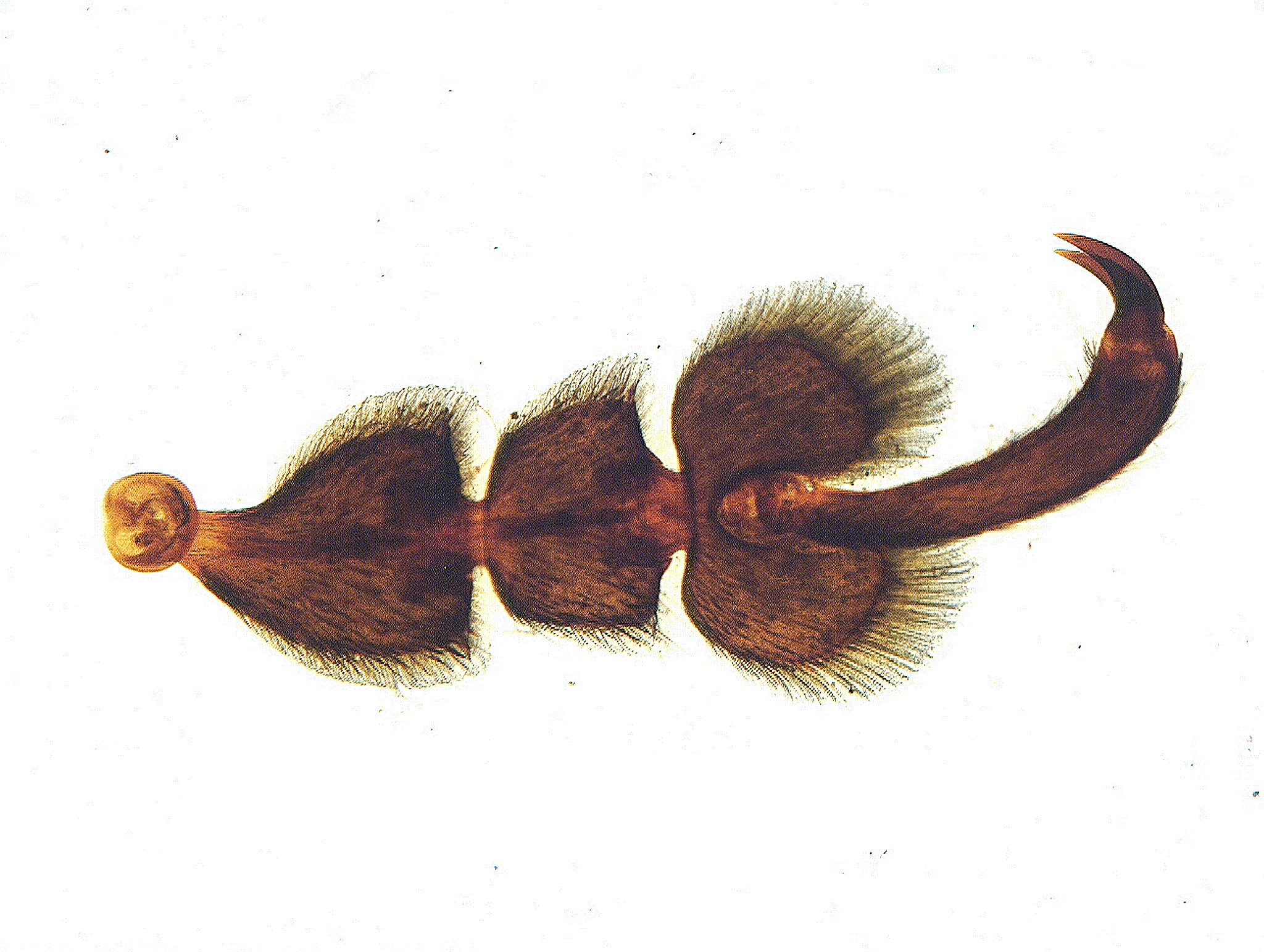

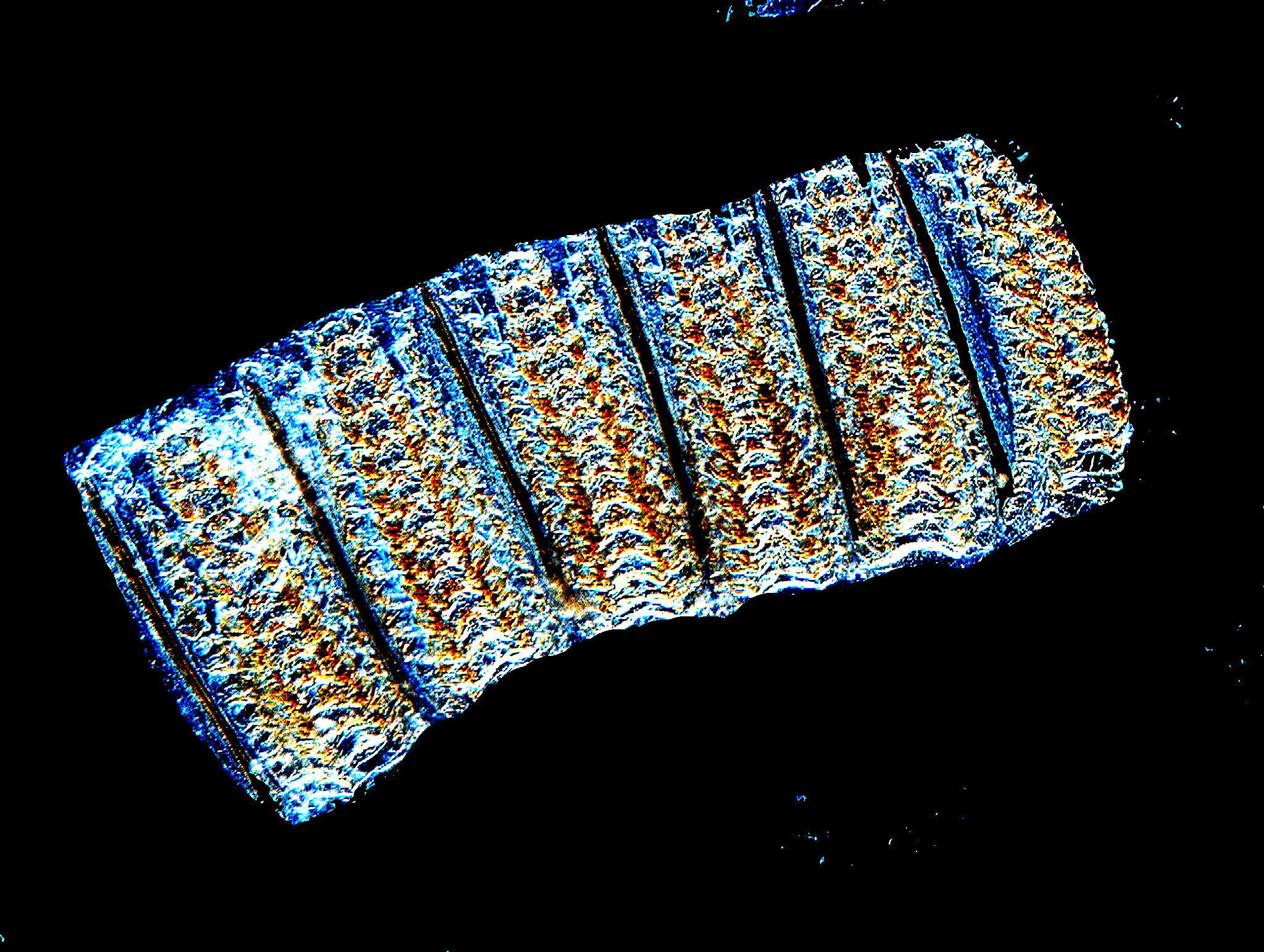

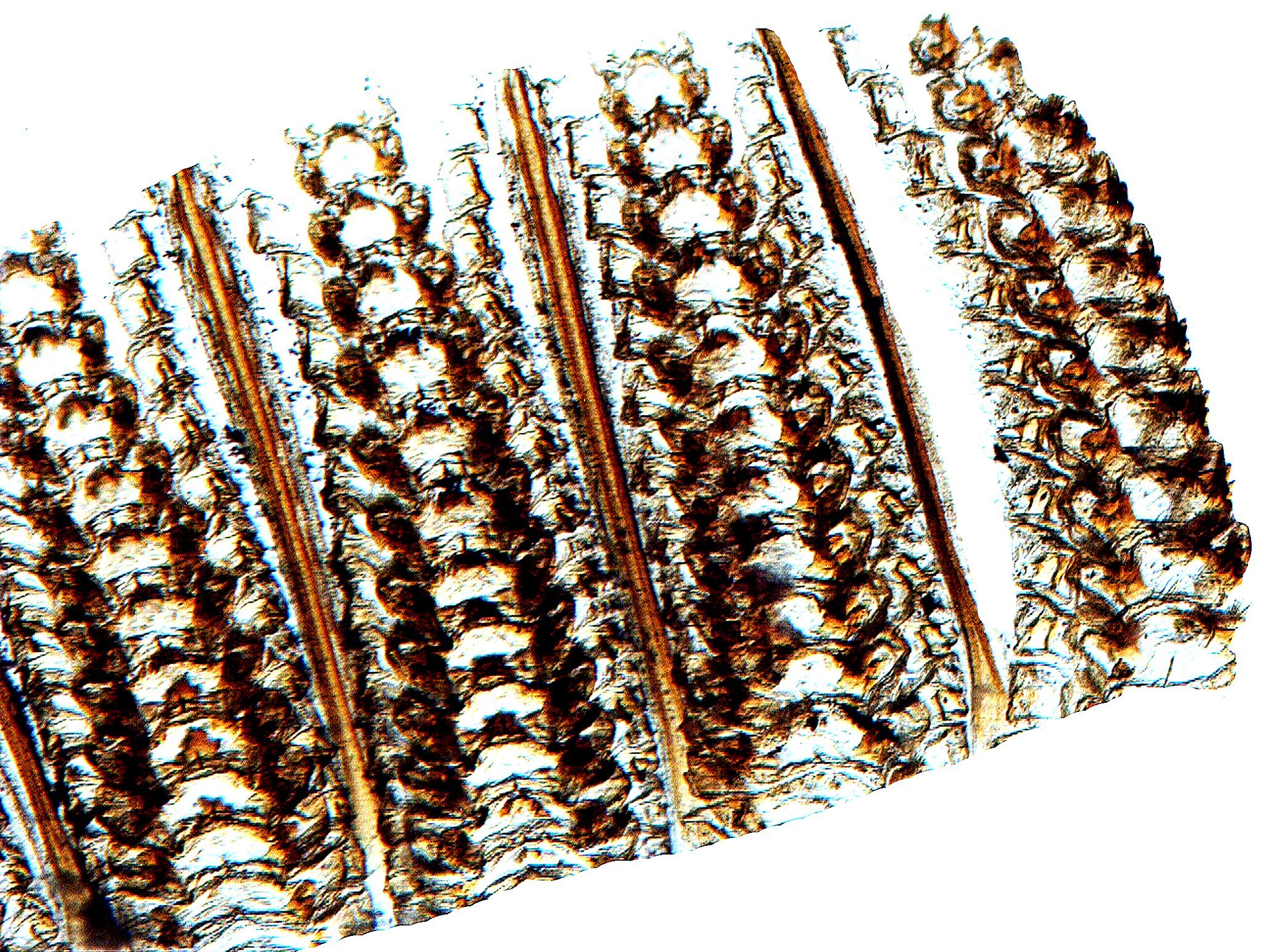

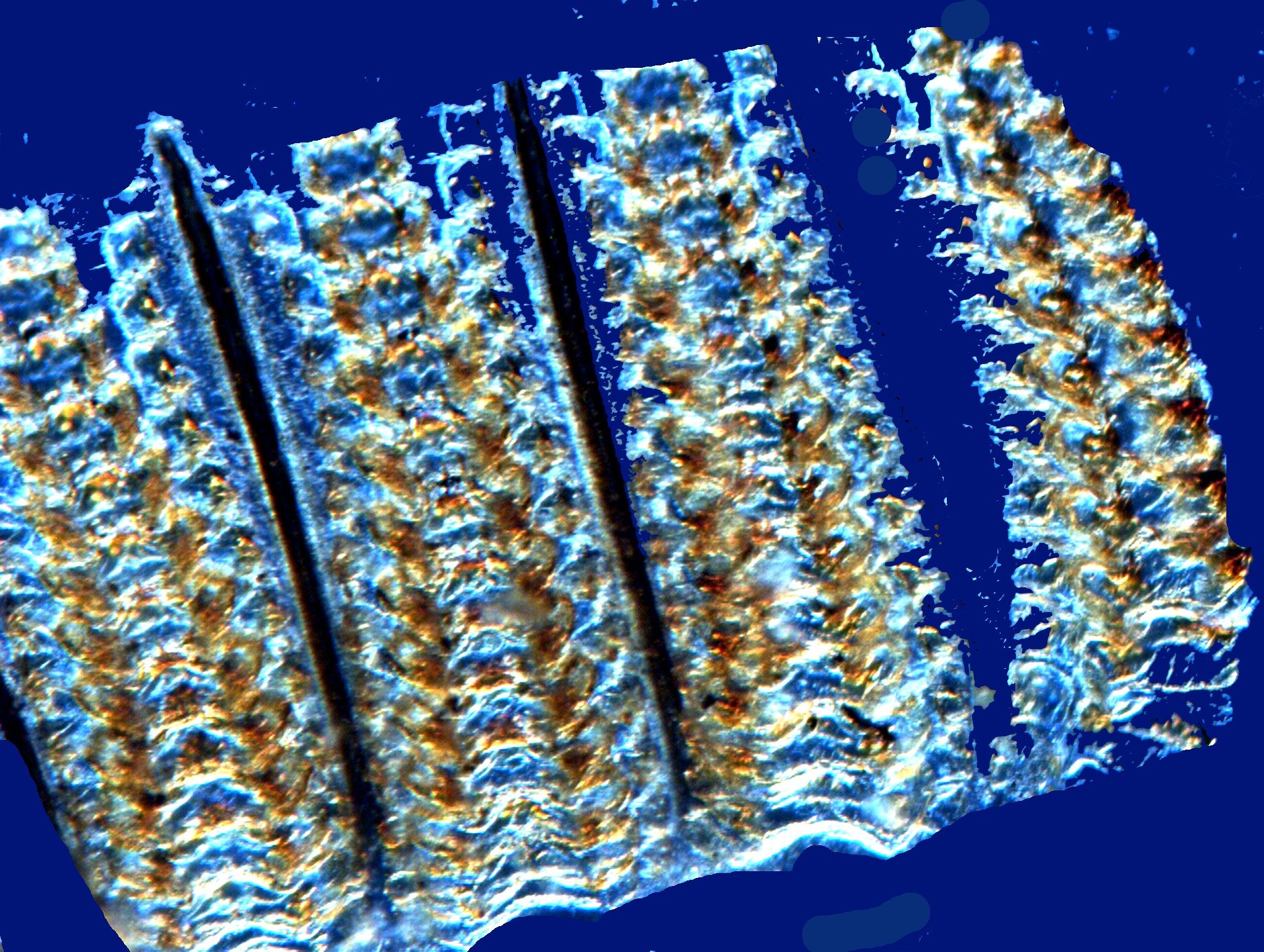

Well, let’s proceed to something that can produce desirable images, in this case, a slide of the gizzard of a cricket. The gizzard in insects is a sort of gastric grinder or mill consisting of “teeth”. First, I’ll show you an image of the entire structure on the slide, using oblique illumination.

This is followed by two closeup images; the first is brightfield and the second oblique.

While we’re on the subject of insects, I’ll show you images from a nice slide of the foot of a water spider. Yes, I know that spiders are arachnids and not insects, but I want to include them here, so there. Both images are brightfield, the second is a closeup.

Onward to another non-insect image, a tiny red spider. The appendages are quite clear, however, the body has not preserved as well. First, an overview and a closeup of the front appendages.

O.K., now let’s go to real insects starting with a couple of red ants, a treat for the amateur myrmecologist. The first image shows you an entire ant, one which apparently is all curled up for a nap. The second is a closeup of the head showing off the eyes nicely.

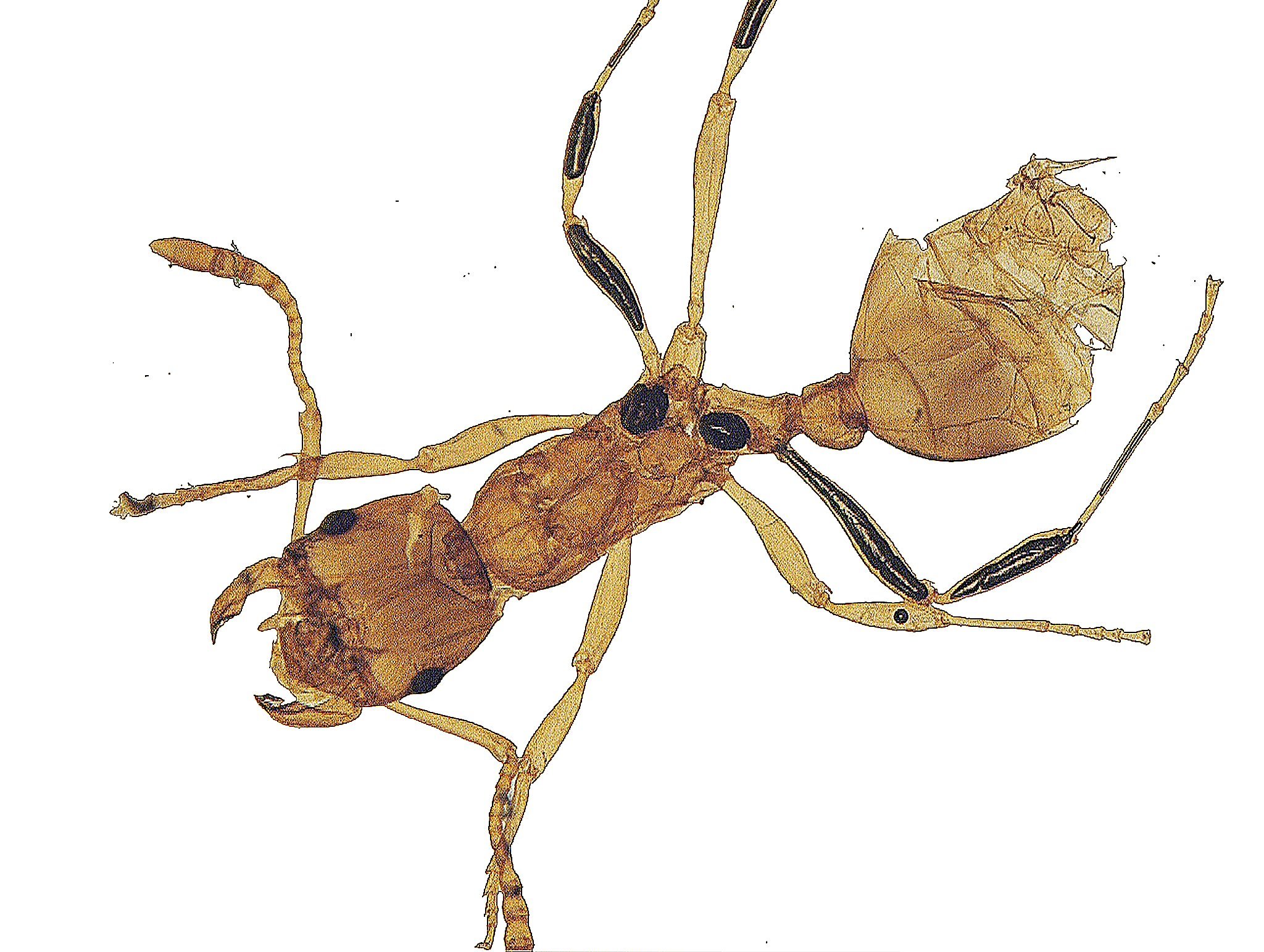

The second specimen is somewhat different and around the head area particularly, as you can see. This ant has mouth parts that look quite formidable, so are these fire ants? Well, as it turns out not all fire ants are red and not all red ants are fire ants. How’s that for helpful? A bit of a check on the Internet and one is told that fire ants have “a 2-segmented pedicel, which looks like two bumps on the 'waist' of the ant—the area between the thorax and abdomen”. So, this seems to fit our star attraction. I’ll show you three images. First, the specimen in its mounting ring on the slide; this is not retouched.

Next, a close view of the whole ant with the background cleaned up and altered in color to improve the contrast. You can see the two “bumps” clearly. And the third view is of the head and the mouth parts which can administer a stinging bite.

Next up is the head of a wasp (probably, some mad amateur scientist guillotined the poor thing). This is also known as the European hornet and has a smooth stinger allowing it to sting multiple times.

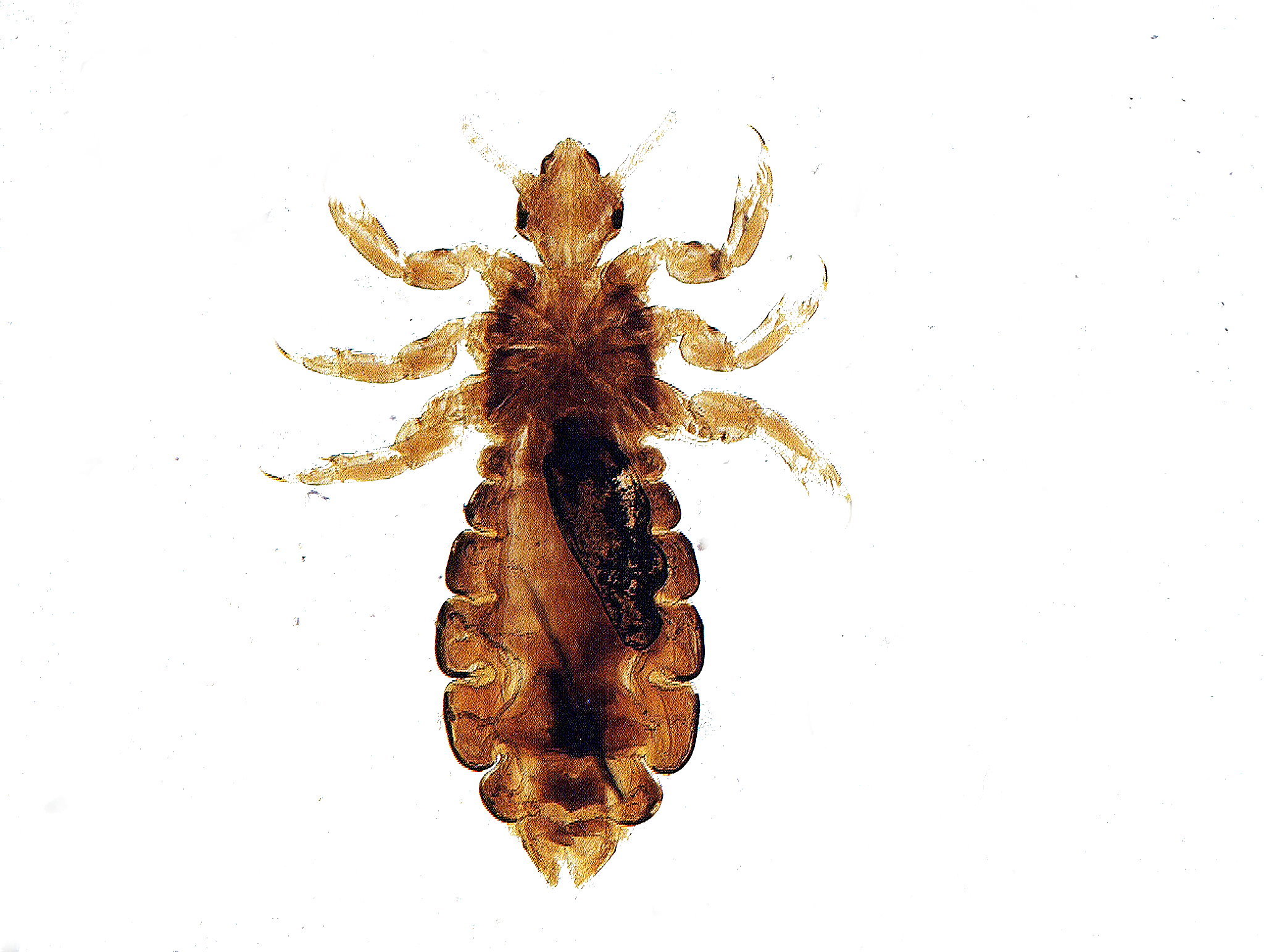

Now we come to a lousy picture, not that the image is lousy, but the specimen is of a human head louse. Thoroughly unpleasant little critters!

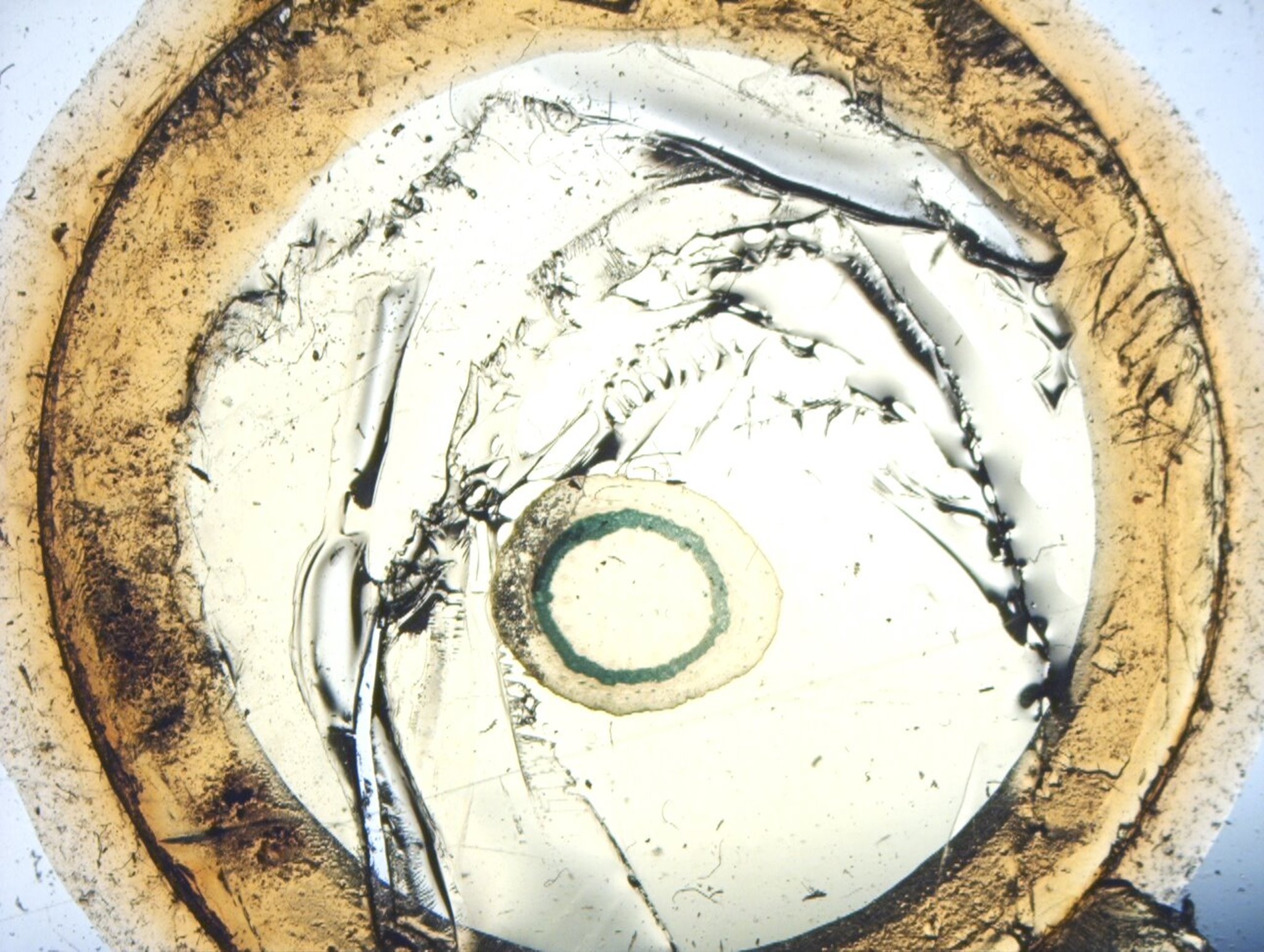

And as the Monty Python crew would say “Now For Something Completely Different”–teeth. Ours, given some of the alternatives that Mother Nature came up with are pretty pathetic. According to the American Dental Association, 90% of American adults have cavities, 25% have untreated ones, and also have an average of three or more missing teeth. Of Americans between the ages of 65 and 74, 57% wear some kind of denture. We’ll begin with a look at the cross section of a human tooth.

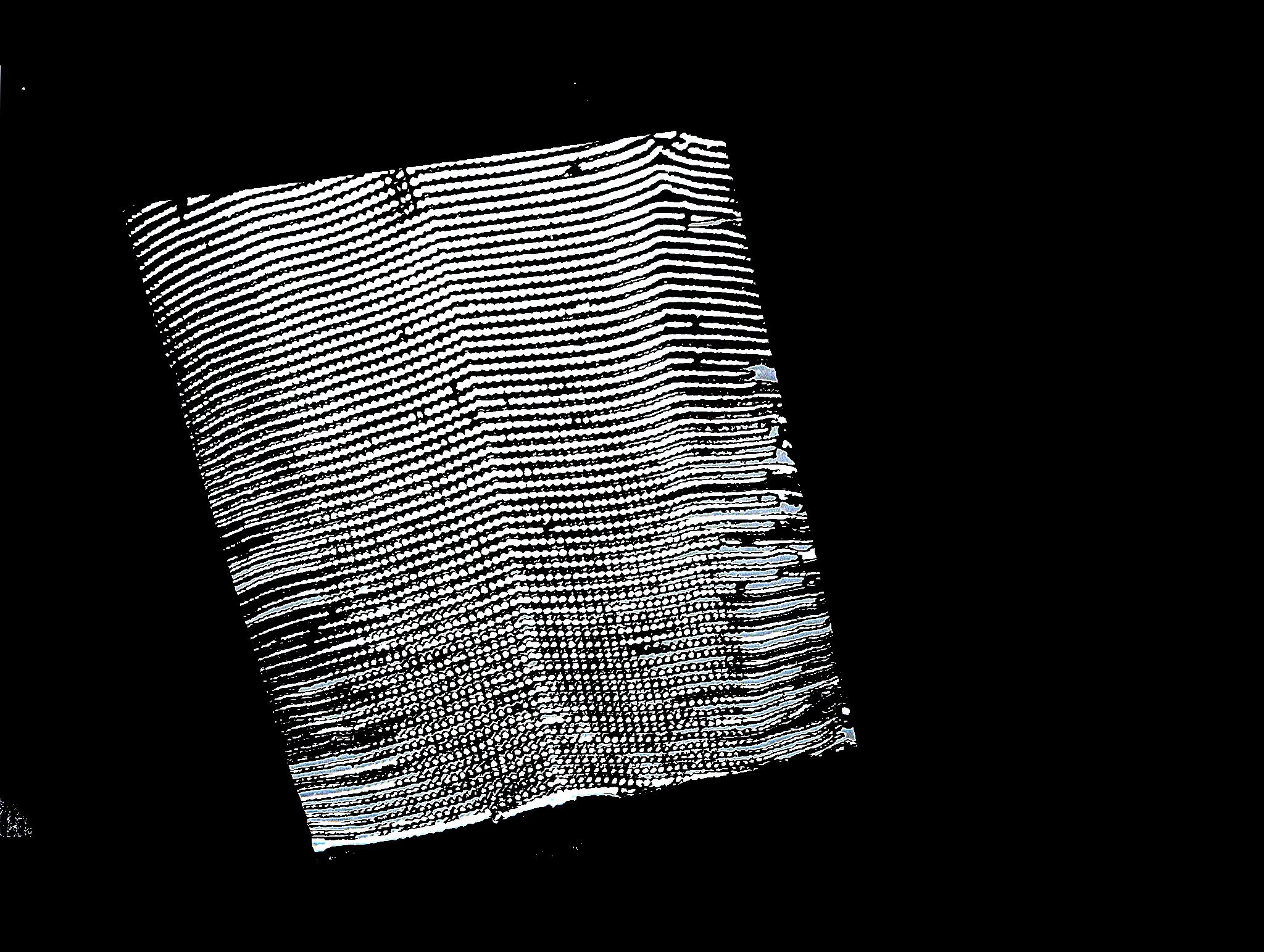

Now, of course, there are alternatives to dentures, the most common one being implants. Even so, I think, we might find some alternatives we could prefer if we are both open-minded and open-mouthed. For this discussion, we will limit ourselves to some example from mollusks beginning with Helix pomatia, also known as the Roman snail. You didn’t know that some mollusks have teeth? You don’t know what you’ve been missing! In this case, a portion was cut into a rectangular section; I have altered it to a monochrome image and added a black background for contrast.

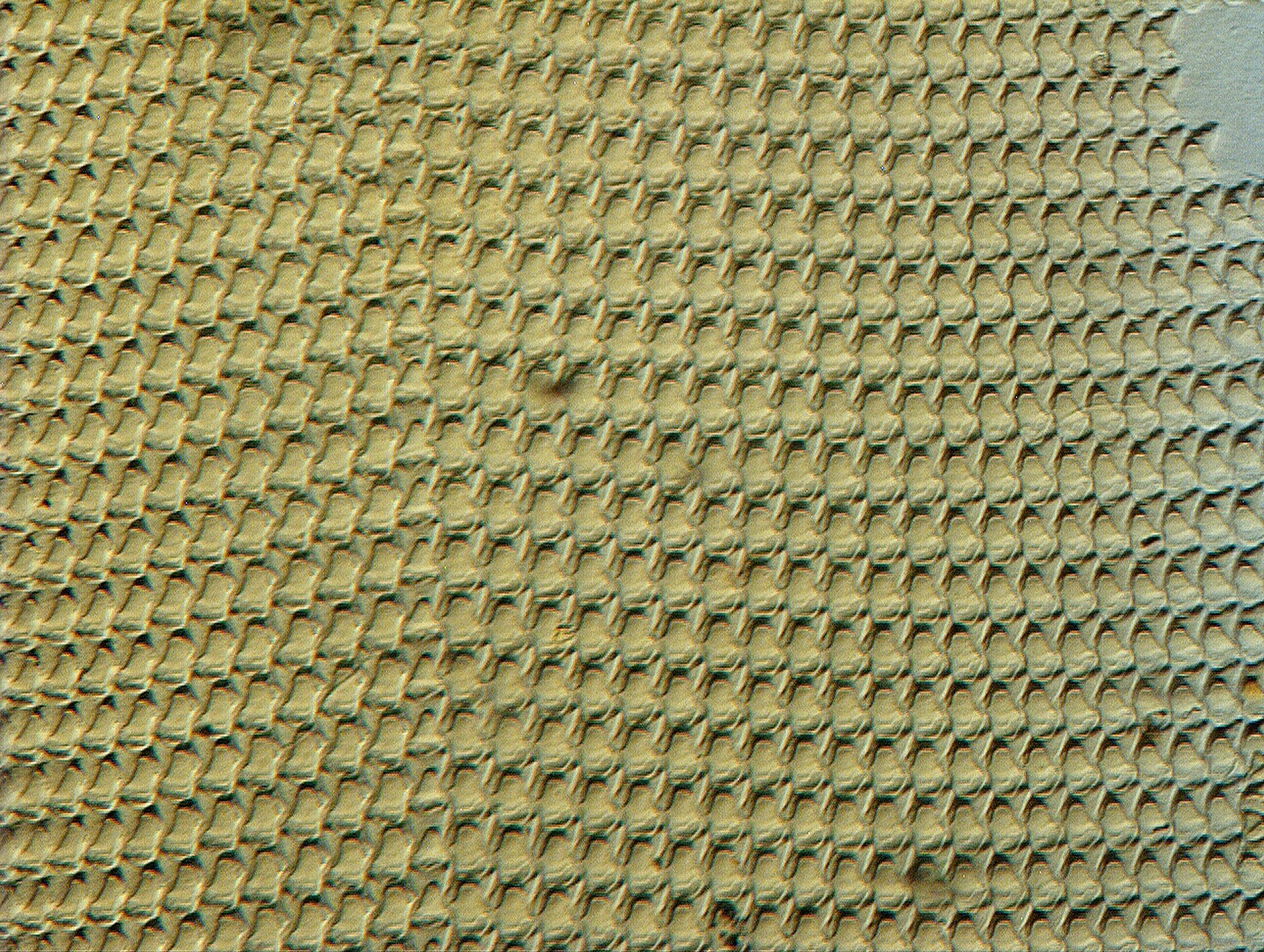

A closeup shows us an incredible array of teeth. The band of teeth or radula is attached to muscles that push and pull it back and forth in a scraping motion thus loosening up food particles, such as algae which are then ingested. This scraping motion causes wear on the teeth, but don’t worry about cavities, the teeth are replaced regularly.

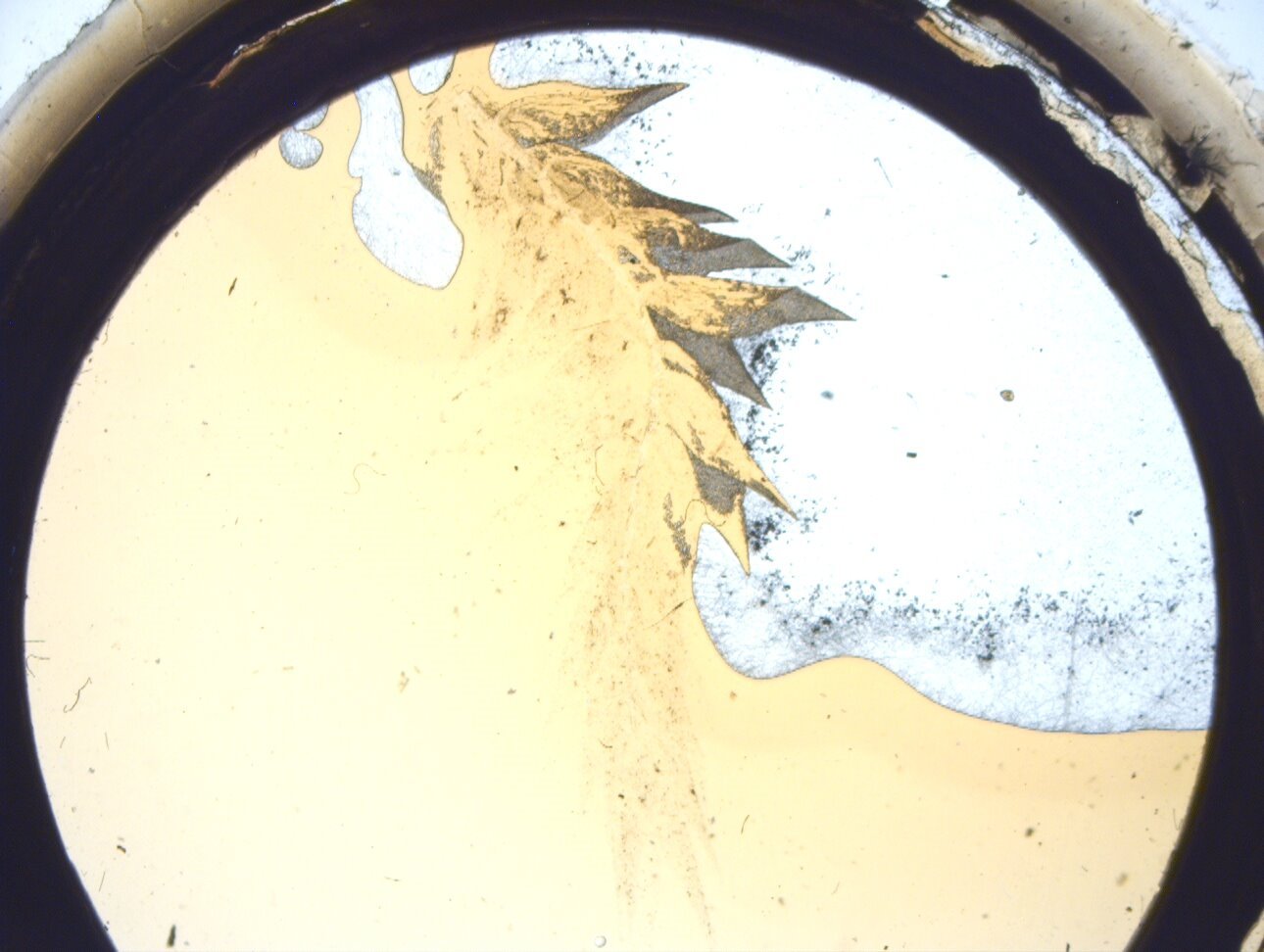

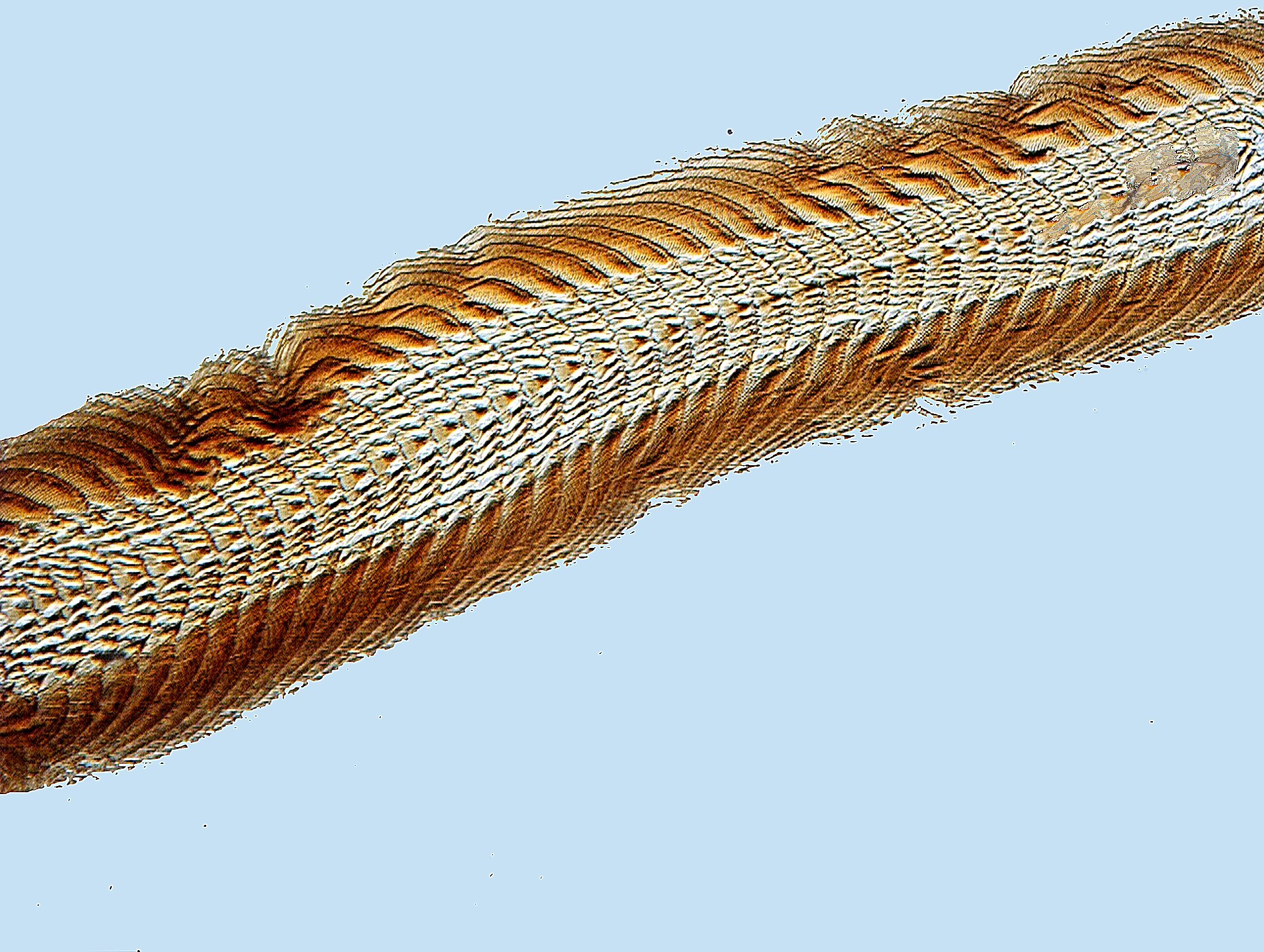

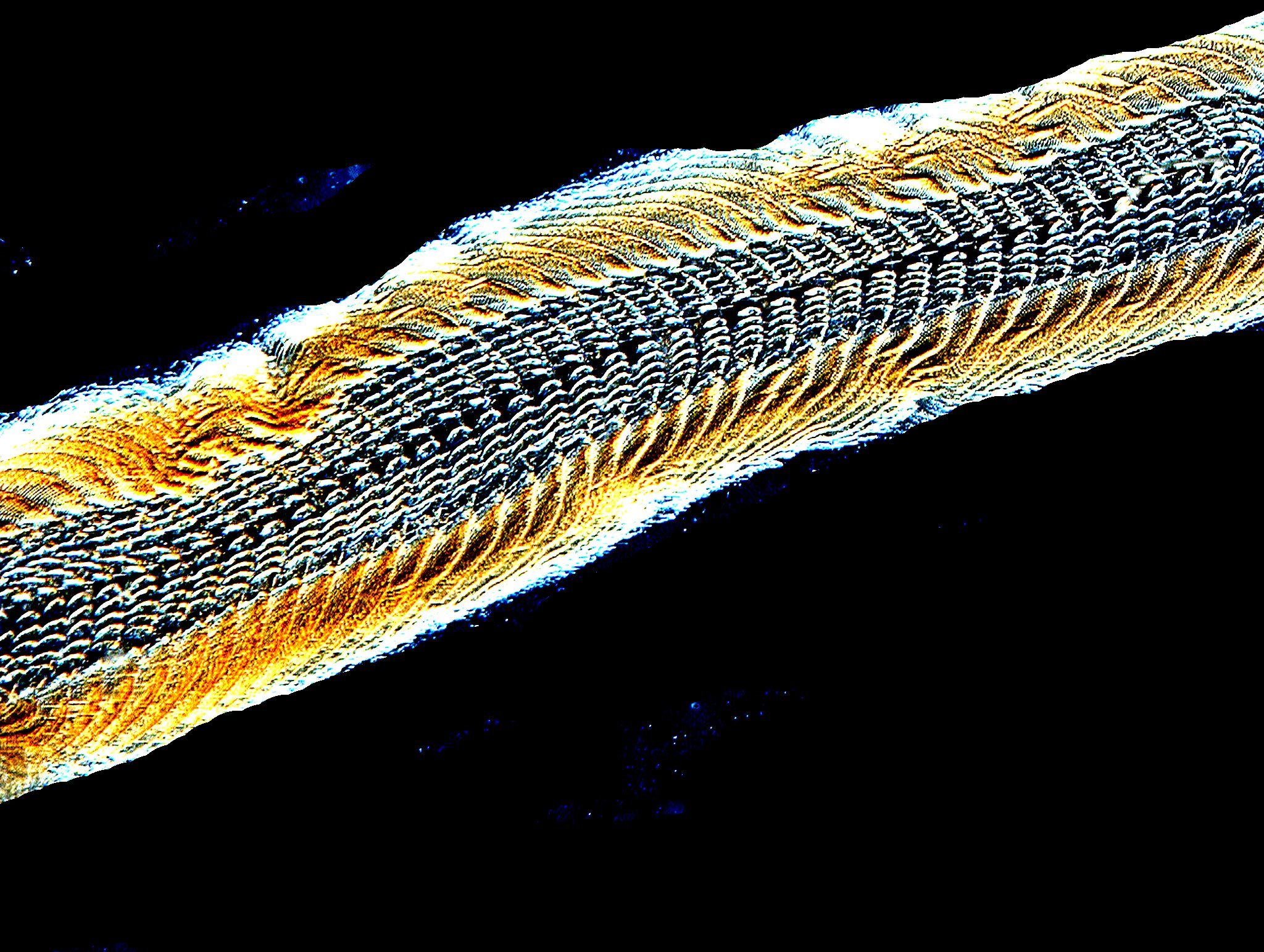

There are even more elaborate and lovely arrangements of teeth and I suspect that Hollywood stars would pay a lot of money to have such arrays if it were practicable. Here are two impressive images of the palate of a whelk.

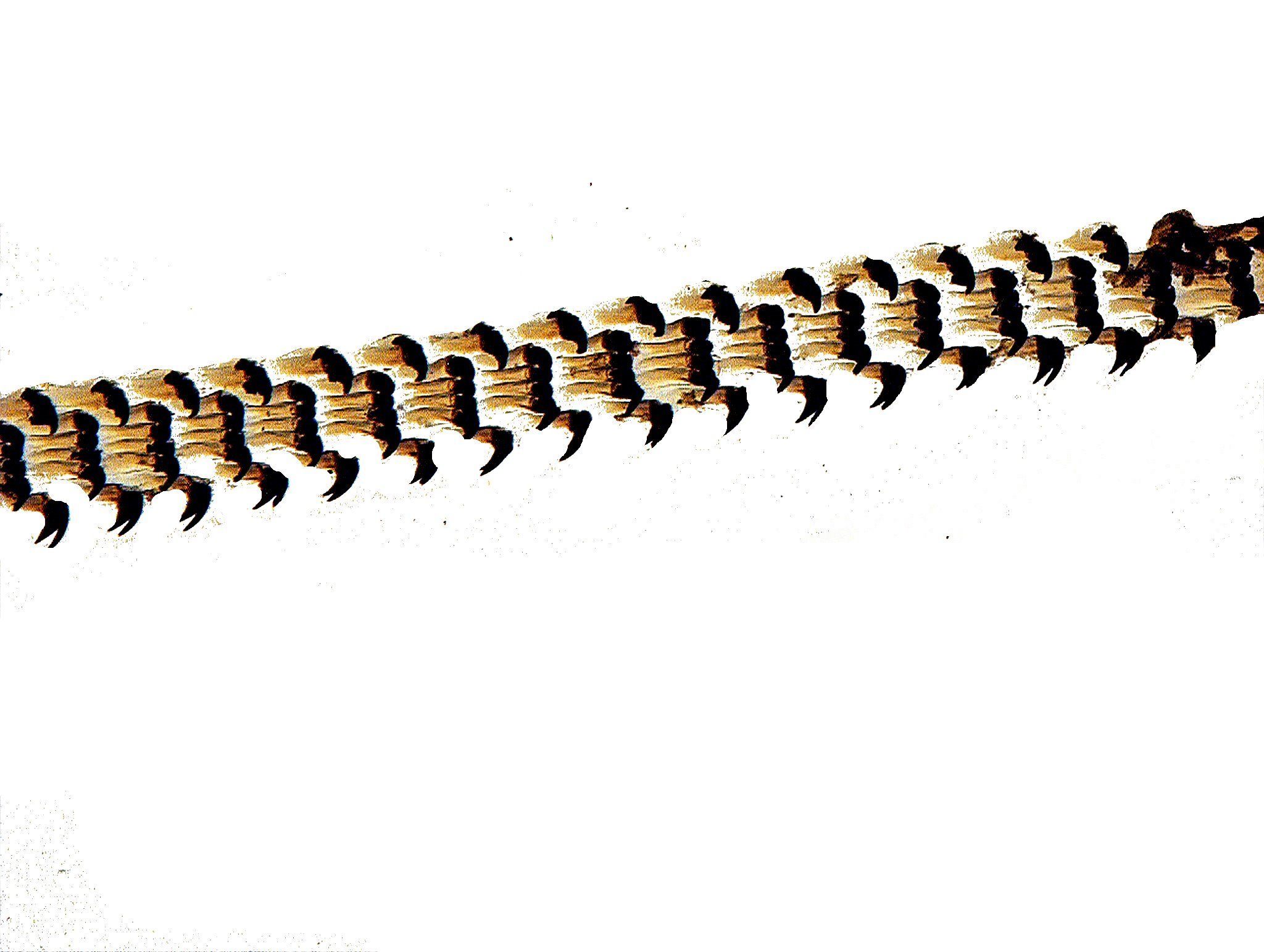

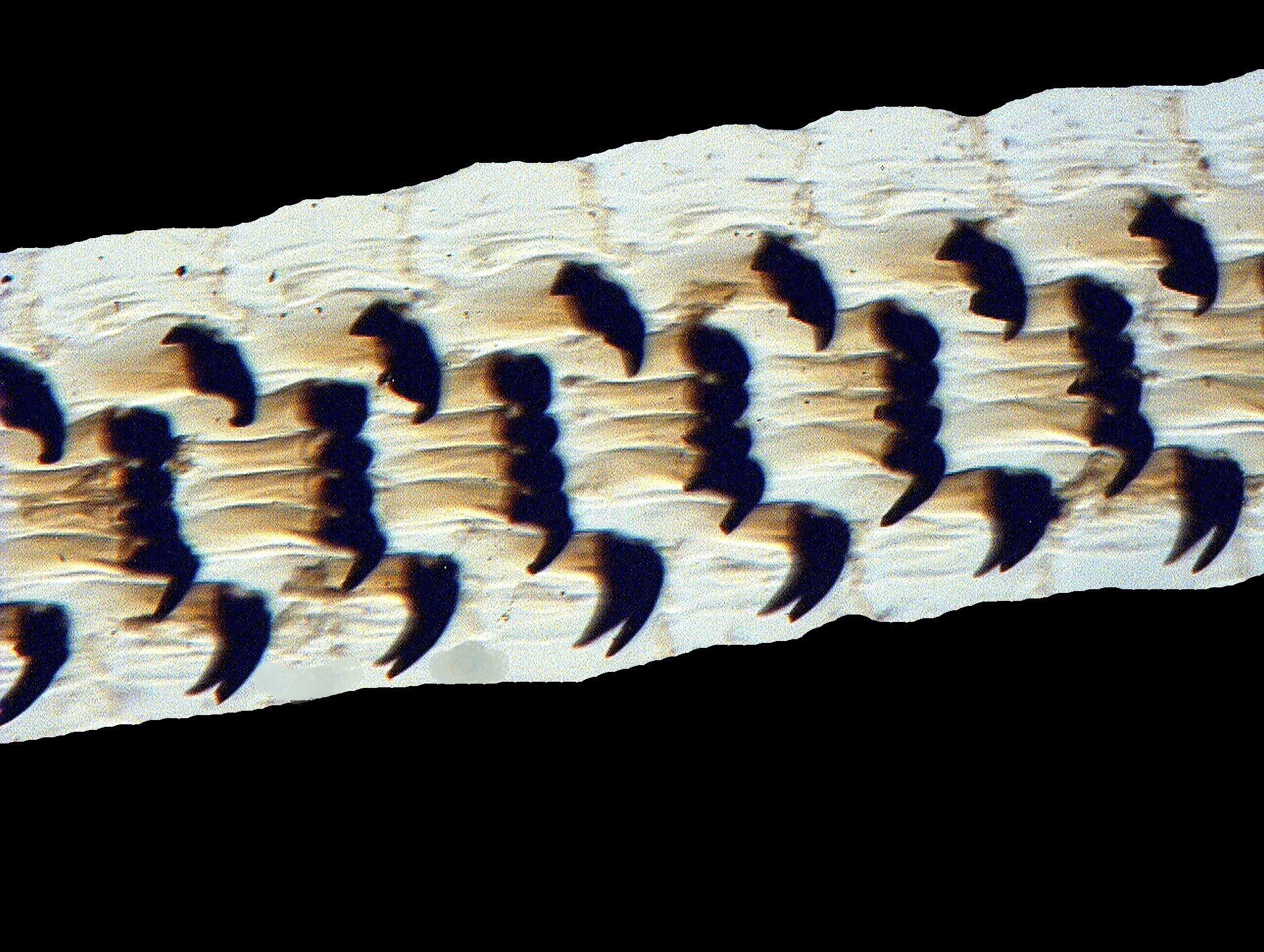

There are also versions which are more suited to the ruthless autocrat type who wants to intimidate. I’ll show you two images of teeth from a limpet Patella vulgata. Calcareous structures such as these radula tend to preserve well but, nonetheless it is remarkable that they are in such fine condition after a century. The second image is a closeup and shows you what look like quite formidable weapons, but you have to remember that these creatures are basically vegetarians–so another myth exploded. We can let the tyrants have all such teeth they want.

As usual, this is getting rather long, so I’ll save some other nice images for a possible Part 3 and conclude here with the hope that you found this little tour through the realm of old slides helpful.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Microscopy

UK Front Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK