|

19th Century Slides Reconsidered by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

I have written previously about older slides and some of the problems with them, of which there can be a wide variety. Rarely does one have the opportunity to examine the slides before purchasing and so one has to do the best one can to insure that the seller is reliable and will accept returns, if the items are not as advertised. Insinuating that you have Mafia connections and could put out a contract on them if there is a problem, is effective, but this has to be done discreetly. Occasionally, a dealer will claim that a problem was with the shipping when there is no evidence for such a claim at all. (This lack of evidence trick is known as the Trump gambit.). Another claim that I have experienced personally is that the shipping company stored the slides improperly and so the damage to the resin was a result of excess heat in one of their trucks or planes. In the instance I encountered, the slides had clearly been stored improperly, but for a very long time and the problem certainly was not recent. On attempting to return the slides, I was told that they didn’t accept my judgment that the slides were in any way defective, but they would give me a 20% refund. I then informed them that this was unsatisfactory and that I was filing a claim against them. The next offer was for a 50% refund. I ended up accepting that, in large part, due to the fact that this was a wooden box of 50 slides which I would have to pack and send from the U.S. back to England. That is expensive, especially with insurance. I was not happy, but I did get the 50% refund and was informed by the seller that they would not accept any future bids from me, as though I would consider making such a mistake a second time. Most dealers, however, want repeat buyers and so are generally honest and fair, but it never hurts to check for evaluations from others when possible.

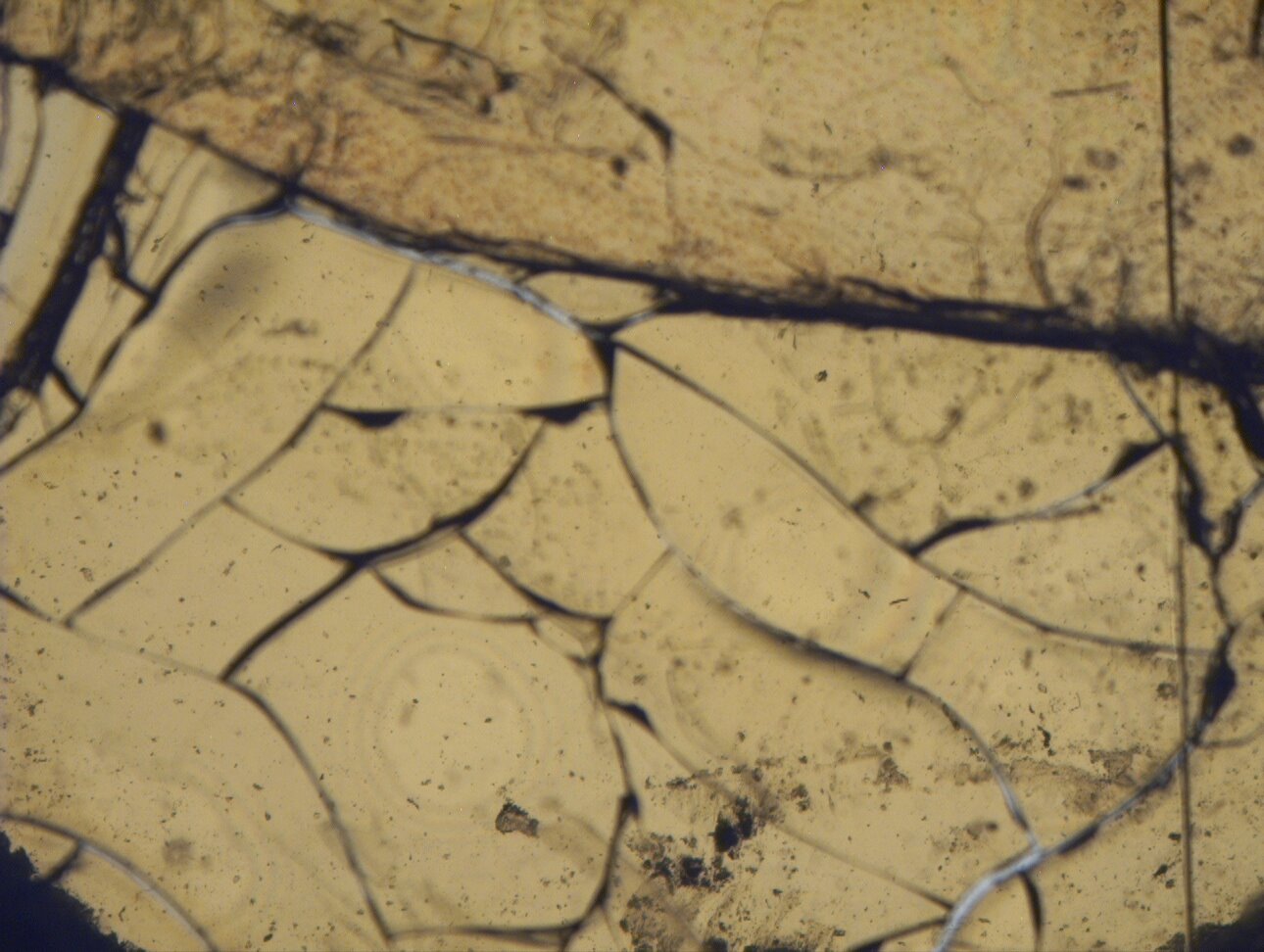

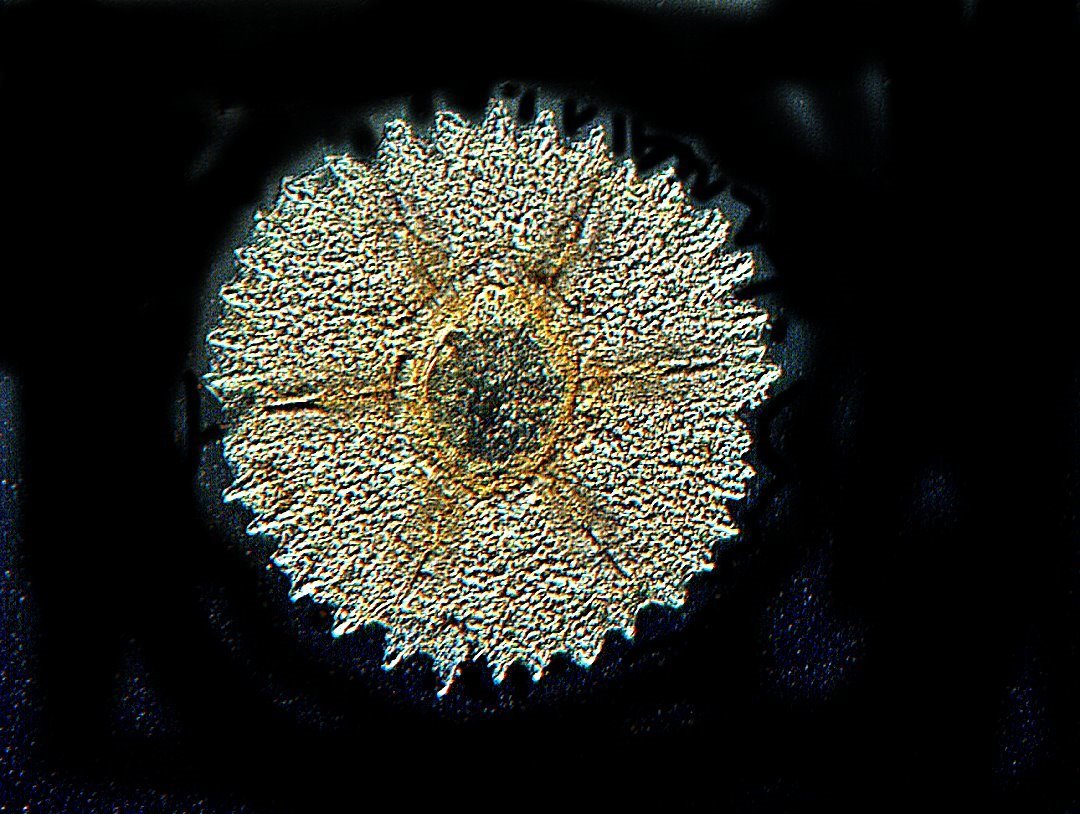

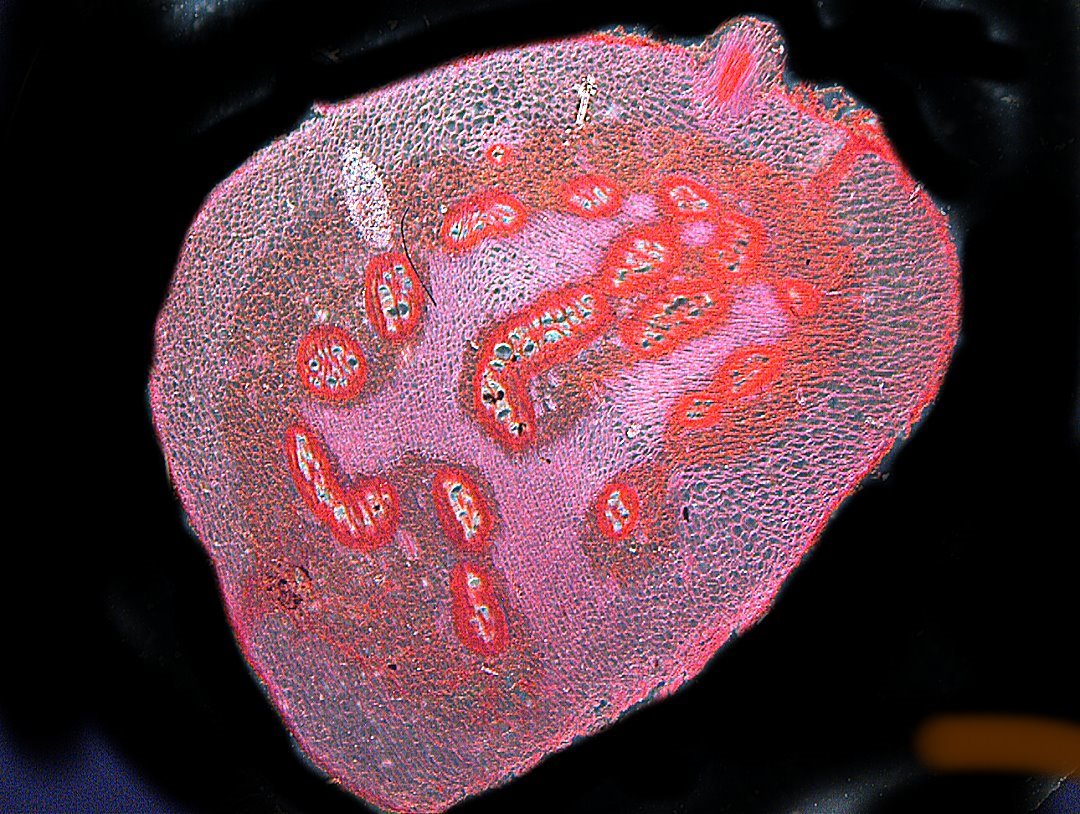

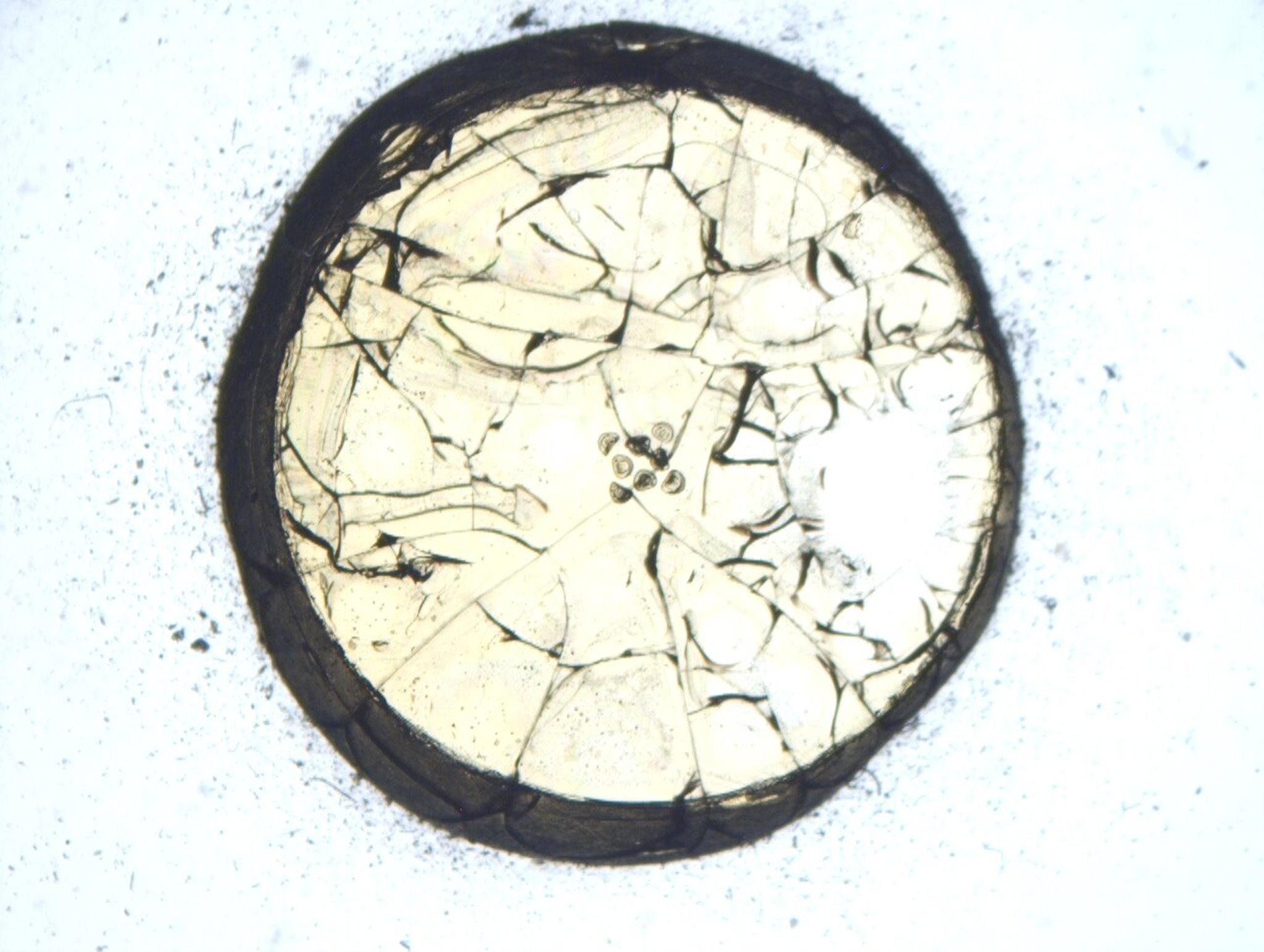

A major issue with old slides is the mountant. If the slides are stored in a place where they receive too much heat, it can cause the mountant to soften and only one tiny gap around a cover slip can allow air to enter in a fashion that will create nice patterns throughout, often ruining the specimen(s). This can cause cracking of the cover glass and even the invasion of filaments of mold. The slide from which the first image below was taken has a printed label stating that it received a Prize Medal. The portion of the label where the nature of the specimen was hand-written is no longer legible.

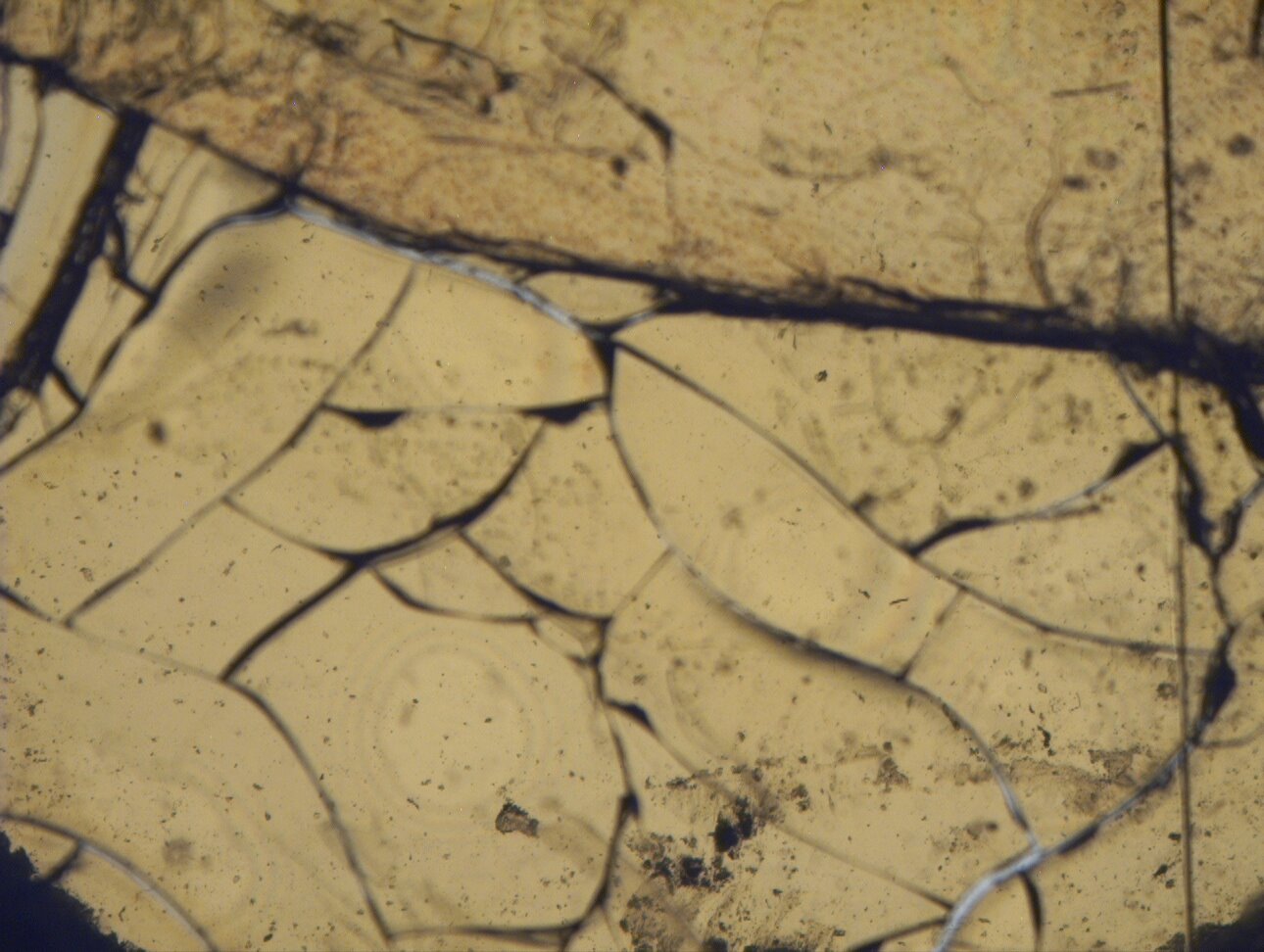

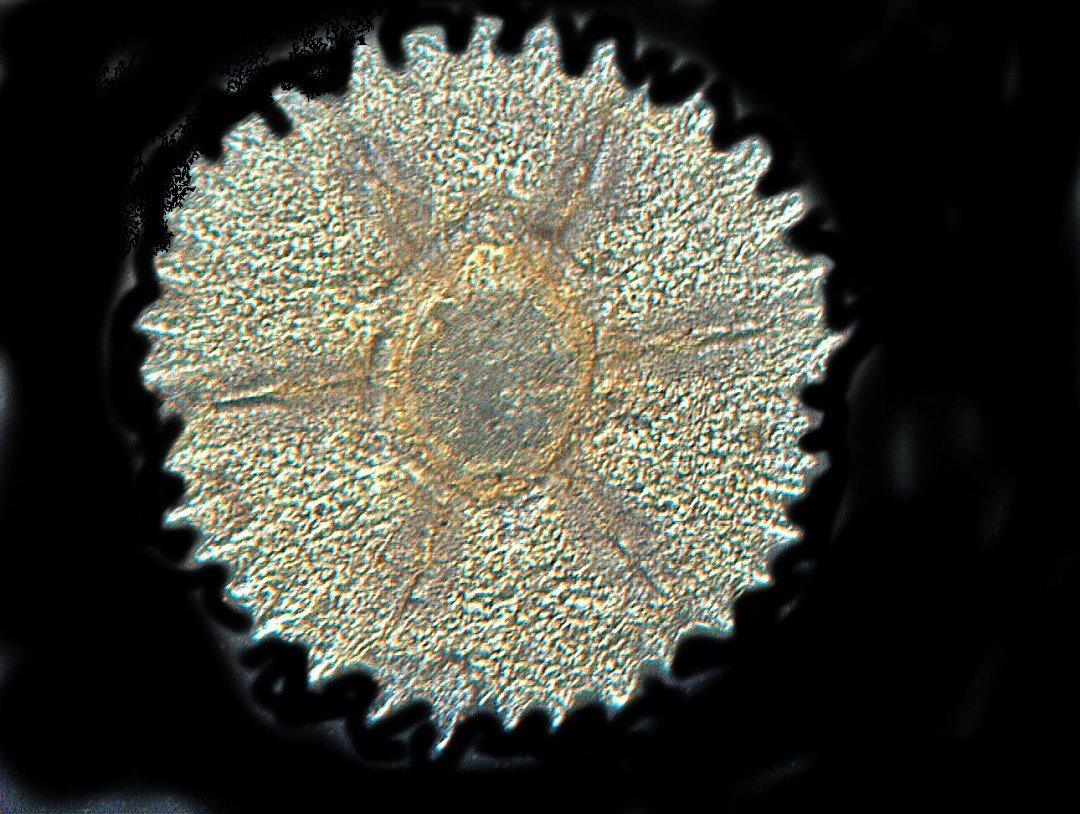

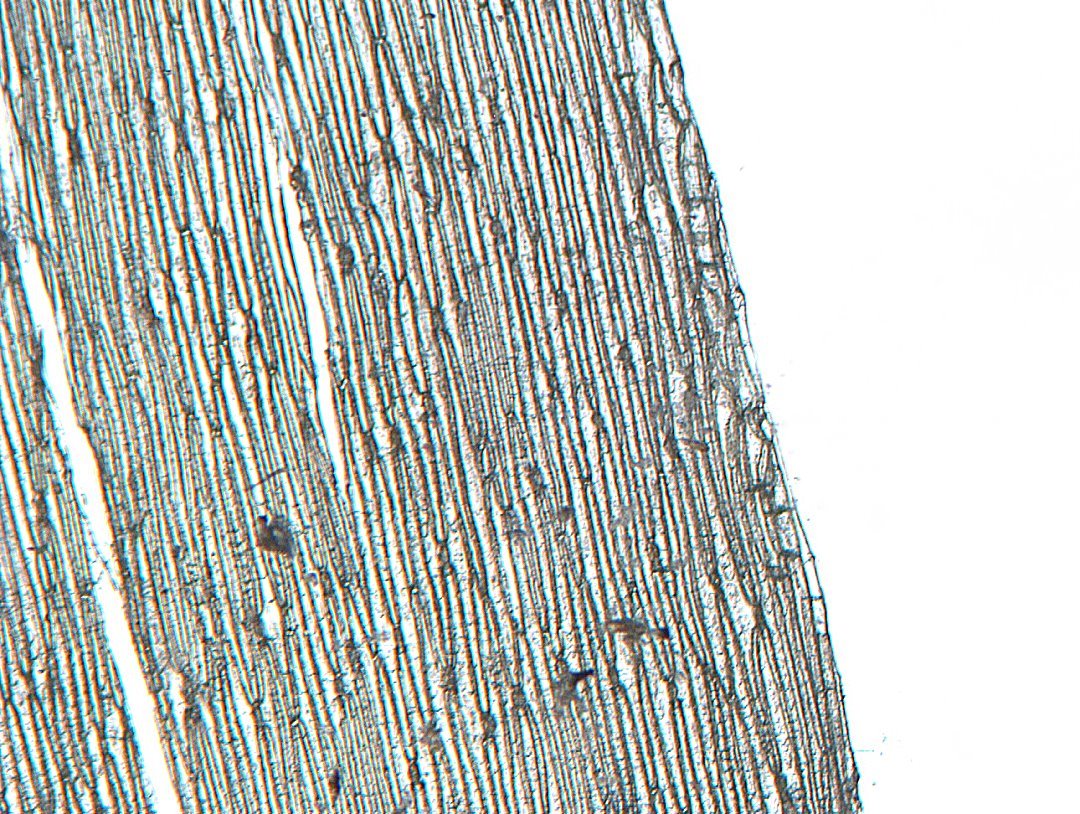

Air can seep in in such a fashion as to create intricate and sometimes interesting patterns. Sometimes, if the patterning hasn’t reached the specimen, one can, with some graphics manipulation, still obtain a reasonable image of the specimen and even “repair” small imperfections resulting from the invasion of the air. Below is an example where the specimen is a fish scale.

The most common mountant during the period we are concerned with here was Canada Balsam, which can be excellent, but which never completely hardens and so is always susceptible to environmental factors. You don’t need a thermostatically controlled storage room; it’s just a matter of taking commonsense measures.

Another consideration when trying to photograph old slides is the glass slides and cover slips. Before thickness of slides and covers glasses was standardized, you find enough variation to create some real problems. Different mounters would have different sources for their glass mounting materials and these could vary considerably, not only in thickness, but in the quality of the glass. In fact, there are some instances where the thickness of a single slide can vary such that one part of the area under the specimen is thinner than another–very optically frustrating.

I am going to show you some examples of 19th Century slides, some of which have seen better days, but still have some interesting material on them. These are from two of those marvelous old boxes which had twelve thin wooden trays, each containing six slides which are easily removed to get to the lower trays. For this article, I am going to use only slides that can be examined by transmitted light at relatively low magnification (80x or less). There are a fair number that are opaque mineral slides or slides that have an opaque backing thus making them suitable only for reflected light examination. These will have to wait for a future article.

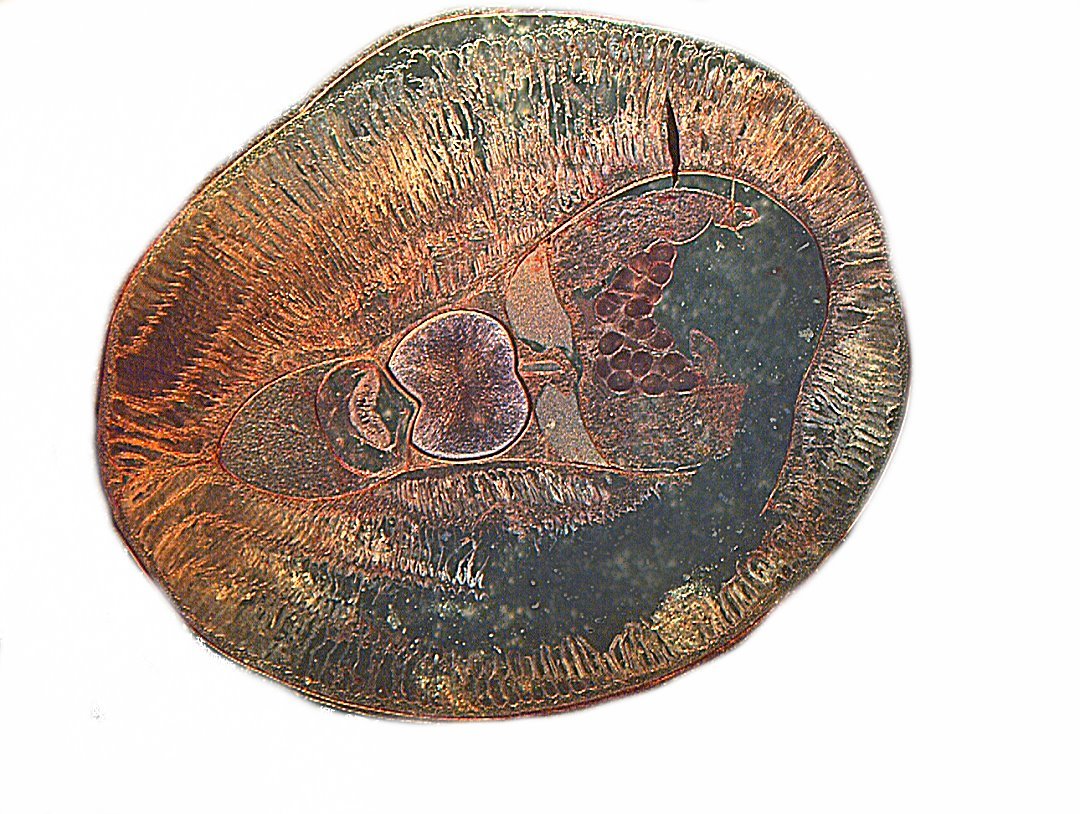

First off, let’s begin with a cross section of a lamphrey. The section was stained, but no information provided about the type or method. The first image is acceptable and shows some of the morphology reasonably well.

However, by increasing the magnification slightly and using computer graphics to alter the contrast and background, a much better image is obtained.

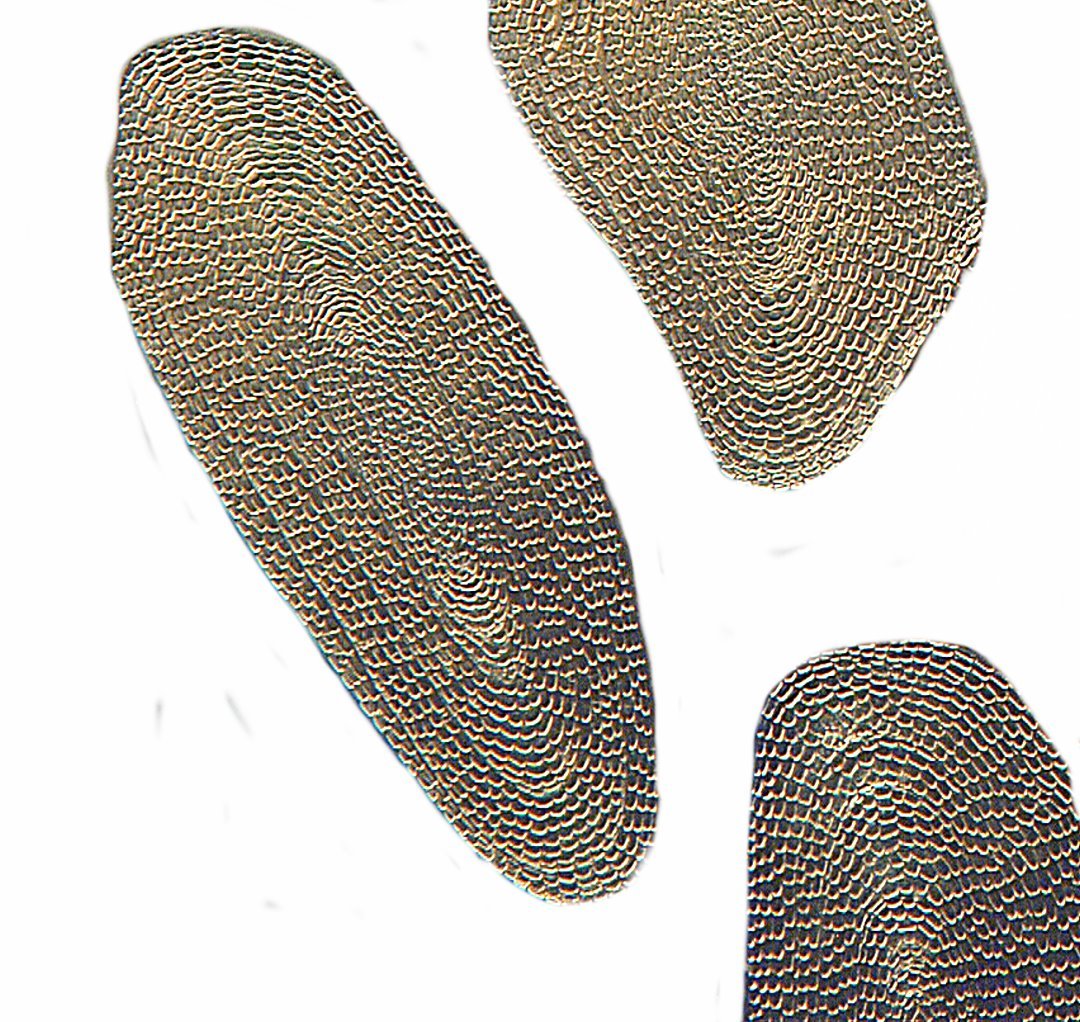

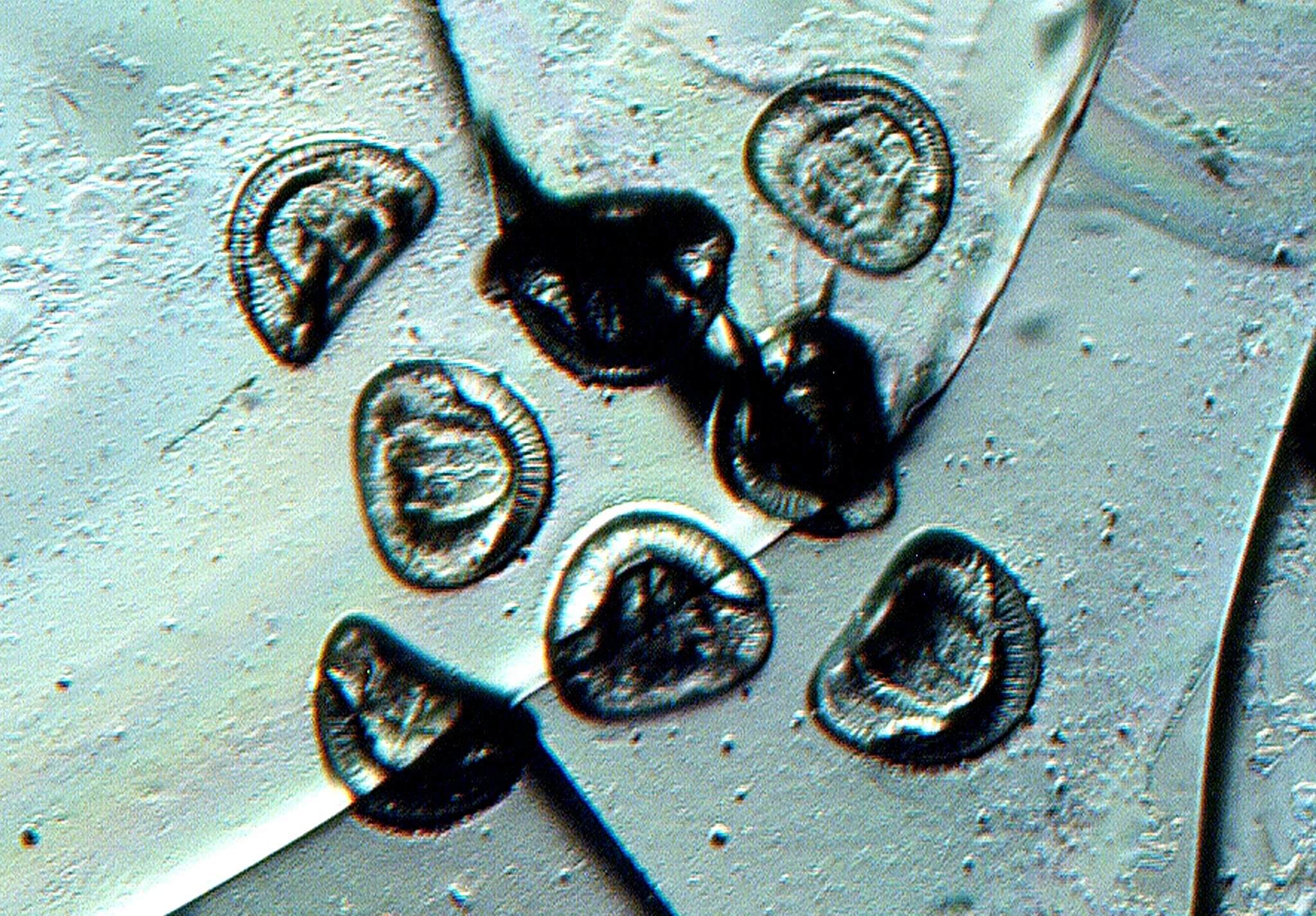

Next, let’s look at the plates in the tube feet of a sea urchin. The slide has 3 plates. The first image shows you all 3 and the bottom one is a bit battered.

Now, let’s take two closer looks. The first one shows more detail and the second one is even sharper and one can get a good idea of the crystalline nature of these plates which are predominately calcium carbonate. These are quite complex structures and provide support when the urchin is applying pressure to a surface.

An interesting botanical slide is the capsule of spores of a moss. I’ll show you two views, both closeups and the second is particularly good in terms of detail.

I’ll show you another botanical slide, this time of a transverse section of a brake fern. As an indicator of the condition of some of these slides (and this is one of the better ones), I’ll first show you the image unretouched and then processed with the computer to bring out some of the remaining detail.

Some slides have labels that suggest a fascinating specimen, but turn out to be quite disappointing. For example, here is an image from a slide labeled “Stomata and Epidermis of a Hyacinth Leaf”. Certainly nothing to write home about.

Fish scales are often of considerable interest and tend to mount and preserve well. The following 2 images are of scales from an eel.

A quite nice slide of a “Zoophyte from New Zealand” shows bryozoa in remarkably good condition.

One should never be in too much of a hurry to reject or discard a slide without careful examination. Sometimes, a slide that a first quick glance at low magnification seems to have no promise can turn out to be quite interesting. I’ll give you an example of a diatom slide that is filled with cracks and seepage into the mountant.

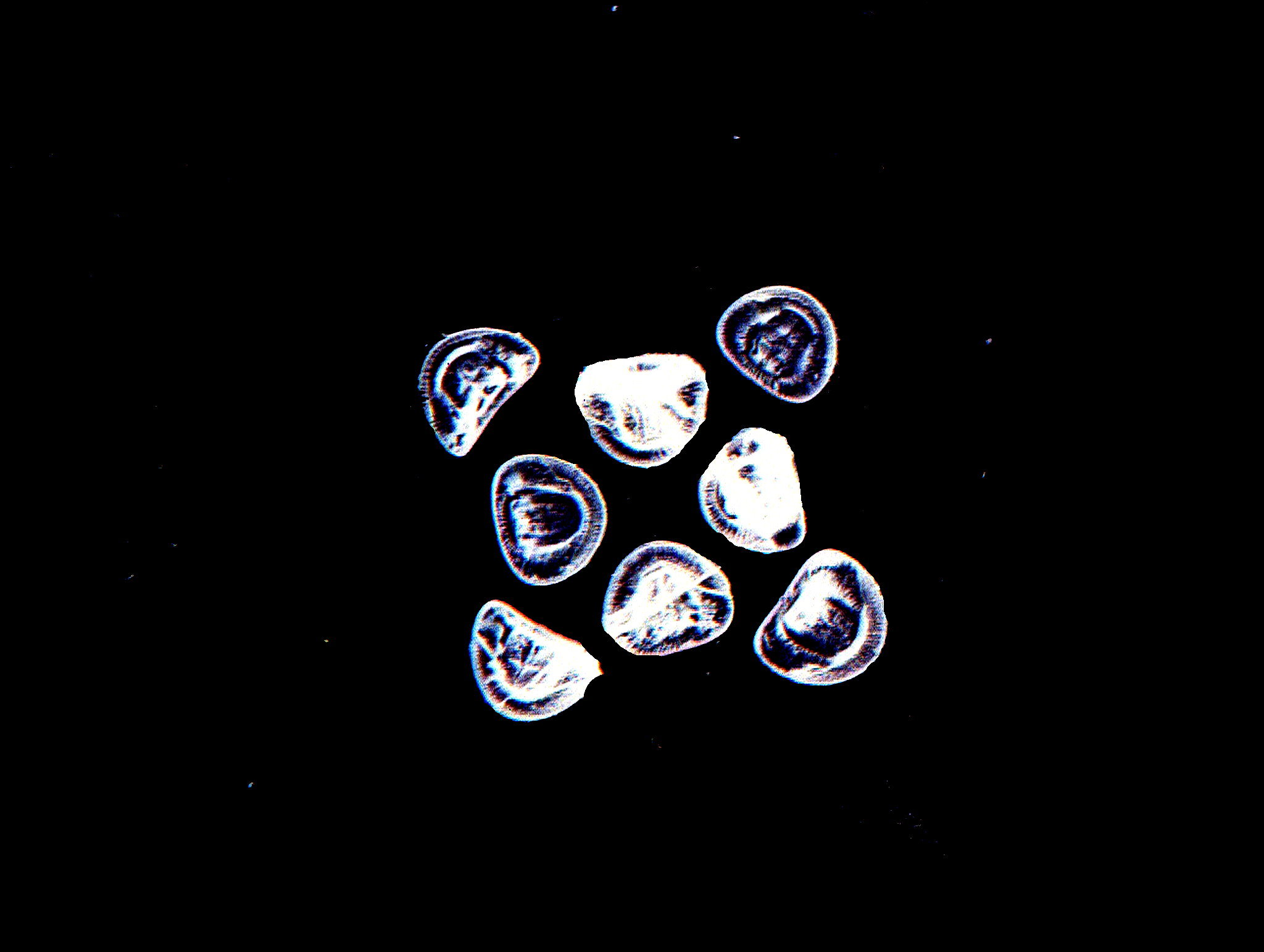

By zooming in on the slide in the central area where this is a cluster of diatoms, I find some specimens that strongly suggest that it would be worthwhile to process some images of this slide. The diatoms are labeled Campylodiscus clypeus. This first image keeps that damaged background.

By zooming out and cleaning up the background, one can get somewhat of an idea of what the original preparation must have looked like. I then took this image and applied the “Invert” function to it.

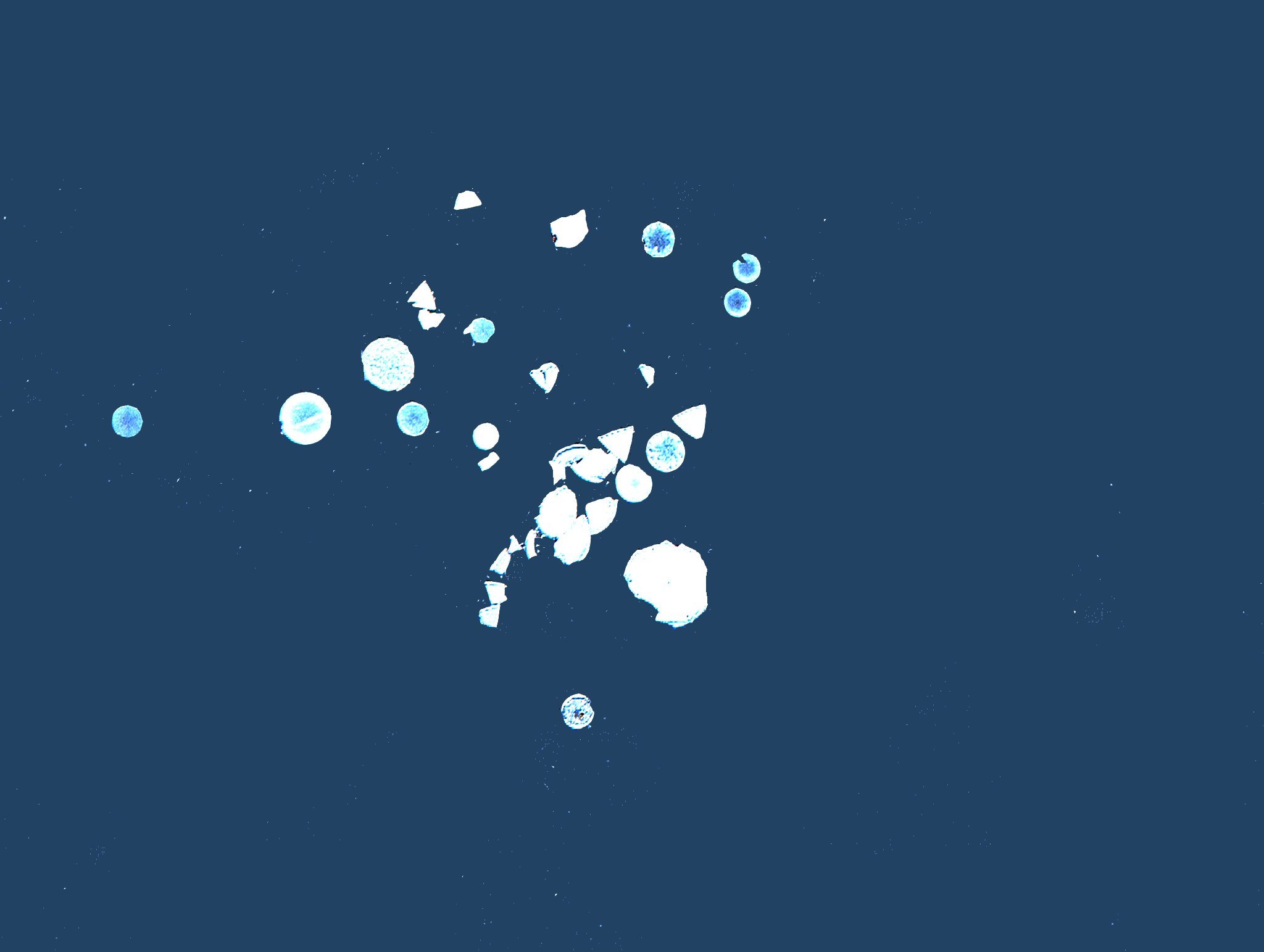

Another diatom slide of a very different character can be seen below. This is a small smear of diatoms from guano of Palos Island. Perhaps more interesting for its source than for the diatoms themselves. I have cleaned the background of this image and altered the color to increase contrast

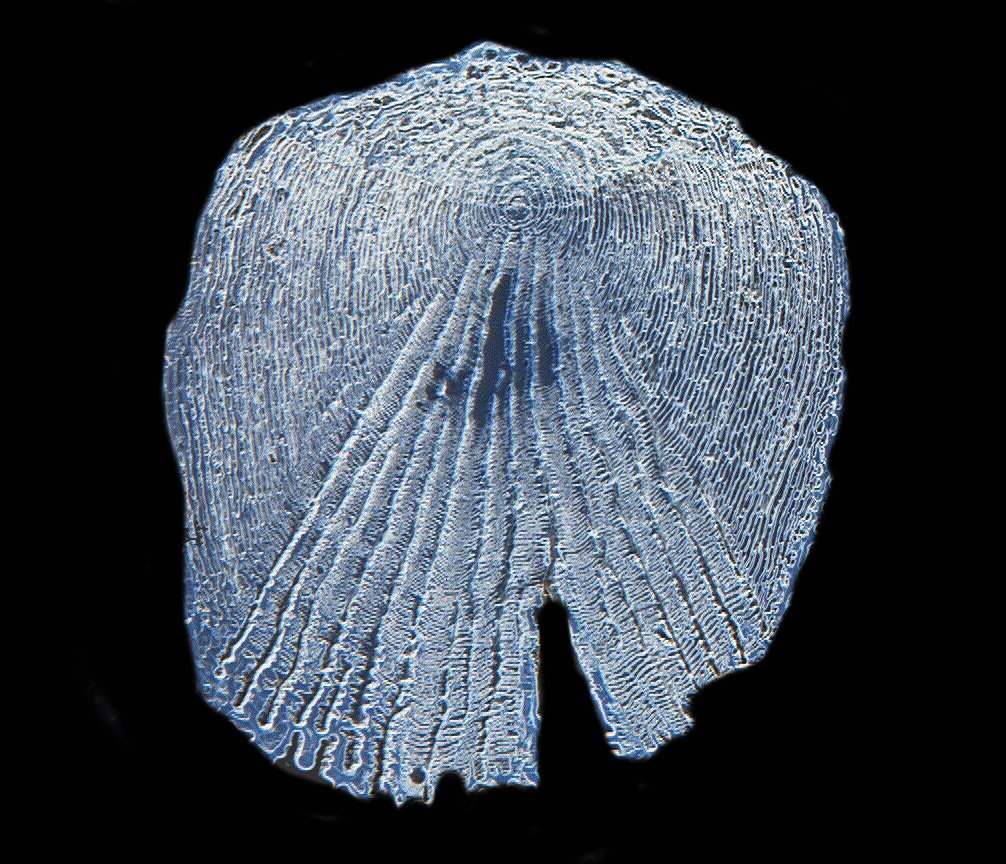

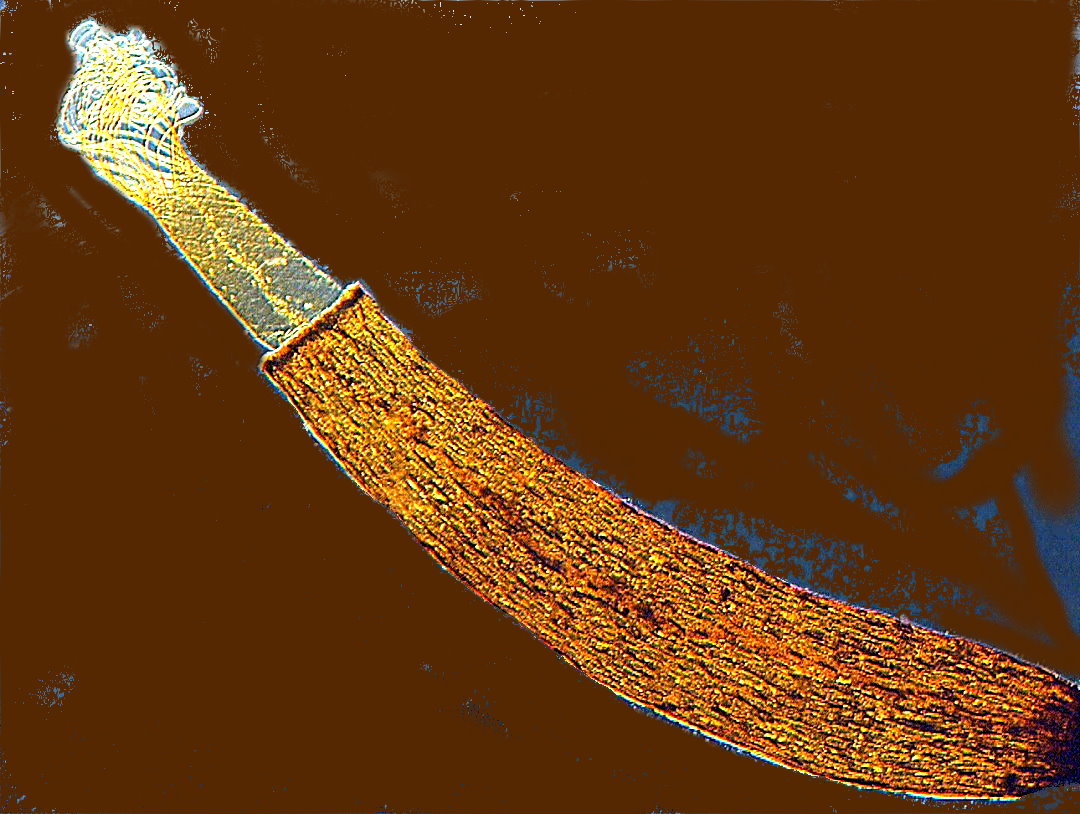

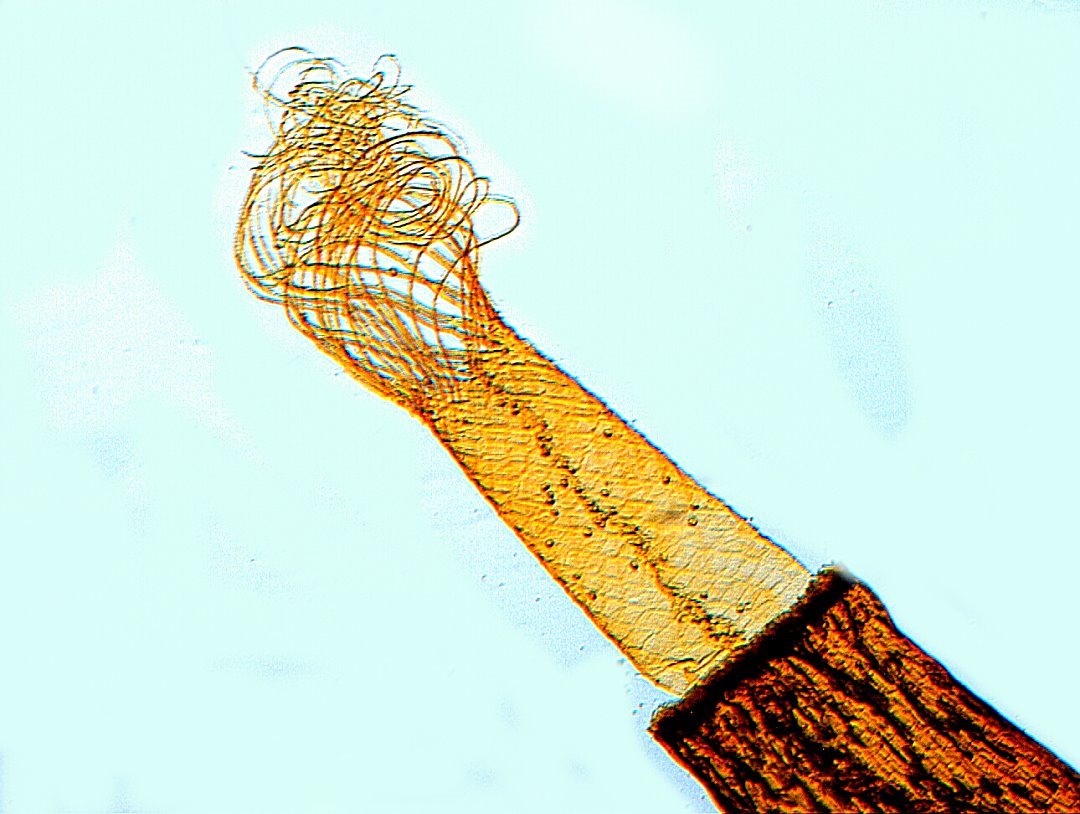

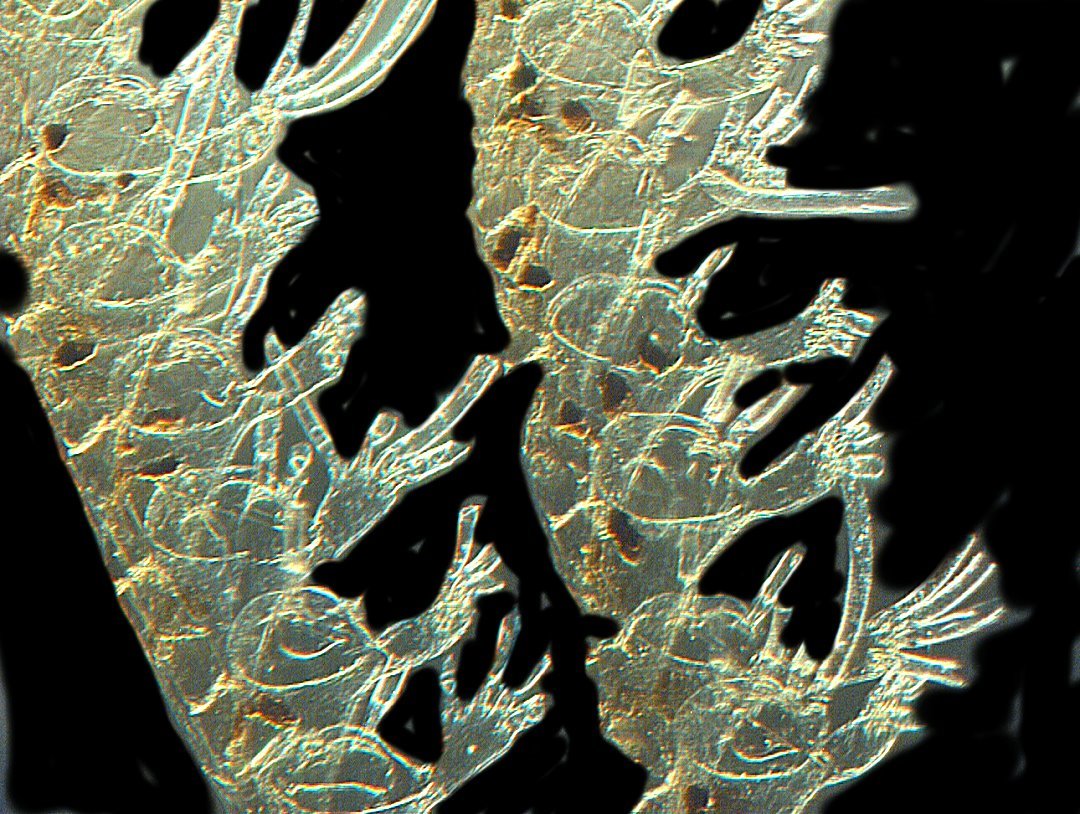

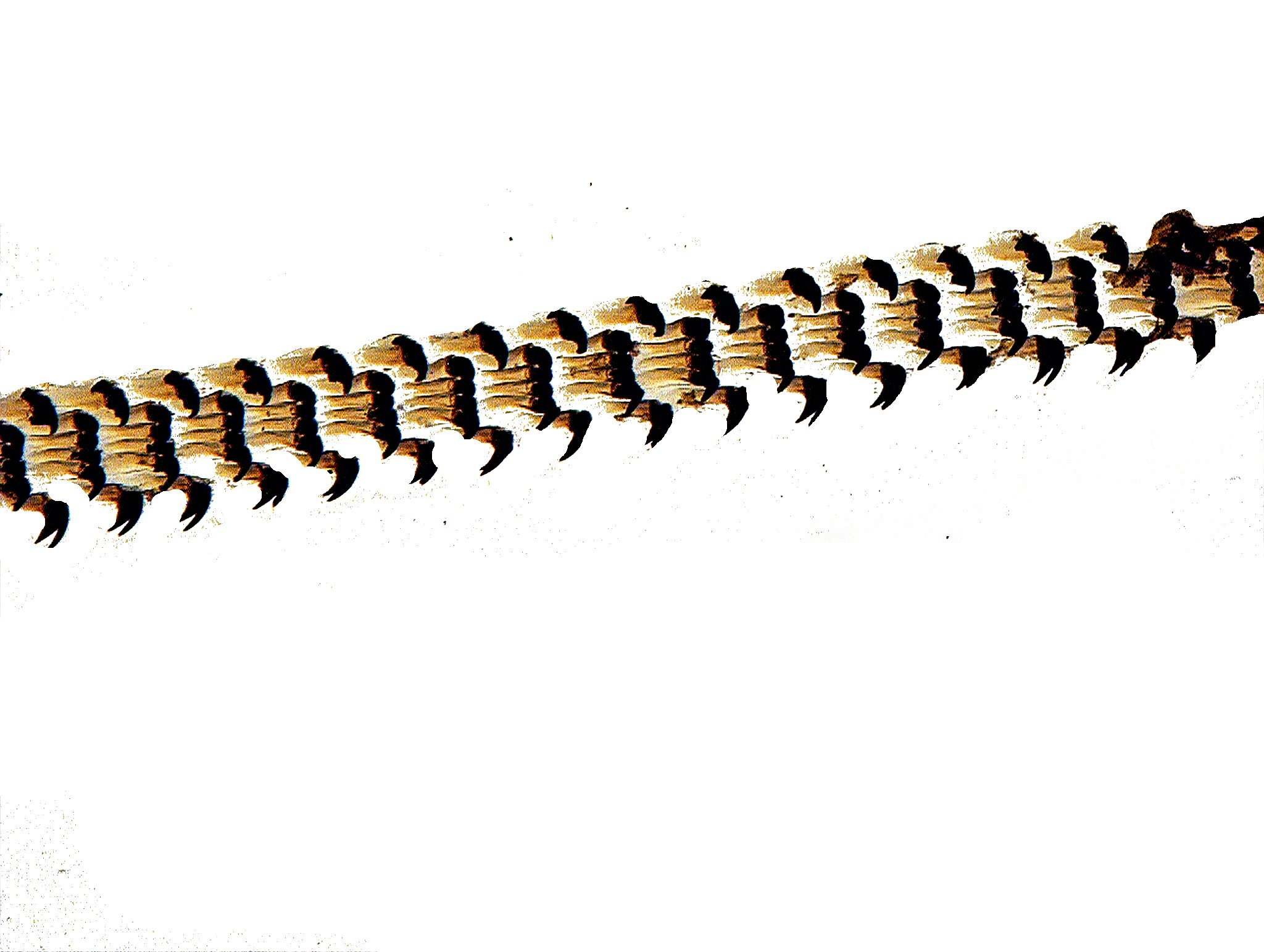

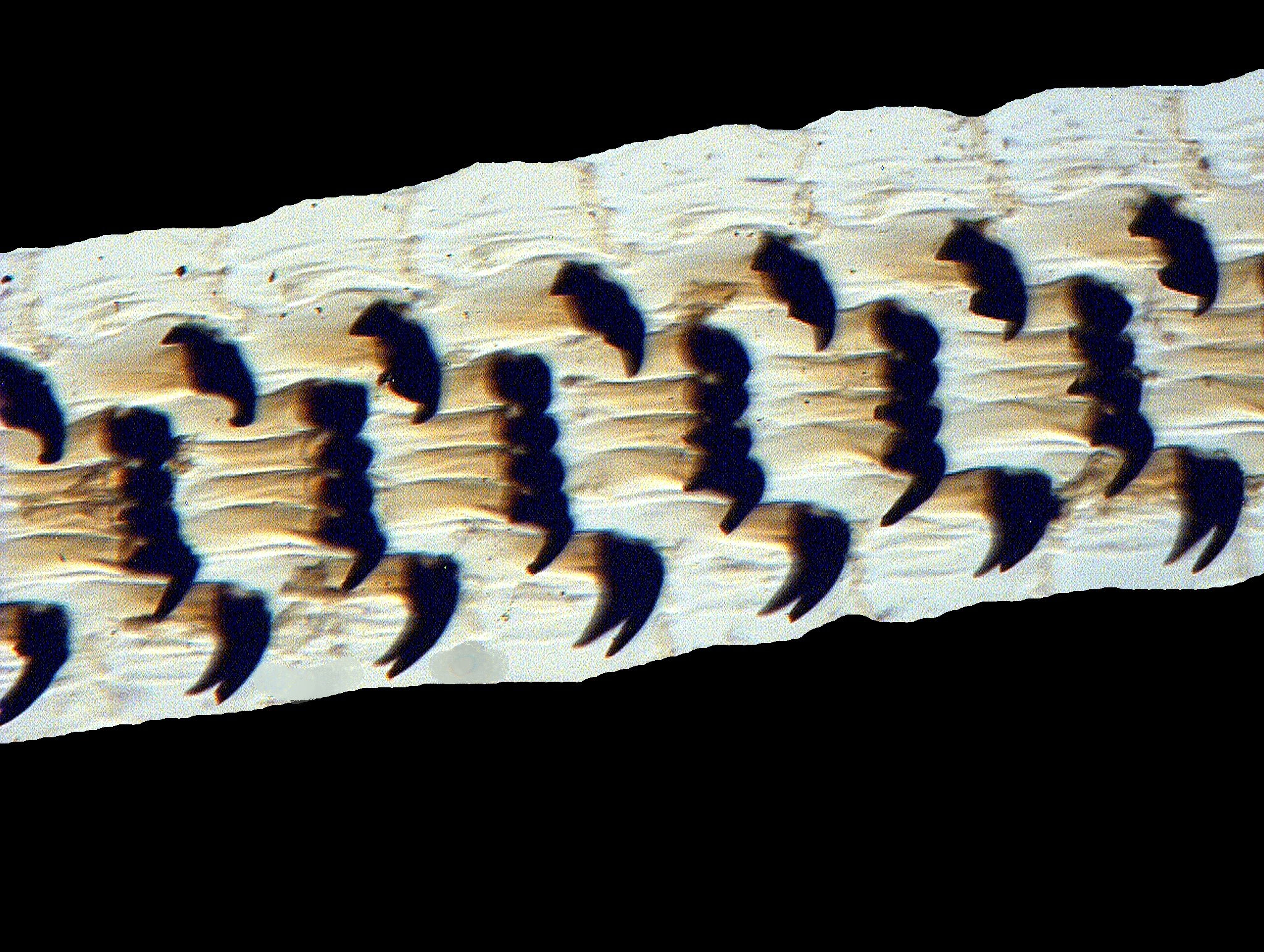

Finally, let’s look at an example of another very popular subject with 19th Century microscopists, the palate of a mollusk showing the teeth; in this case, Patella vulgata, a limpet. Palates or “tongues” of snails, whelks, limpets, chitons, and other mollusks were coveted by some collectors and one can see why; they can be quite impressive. I’ll show you a view at low magnification and then a closeup.

As I browsed through these boxes of old slides, I discovered many fascinating subjects and some surprisingly good specimens given their age. This is just a sampling to whet your appetite. Clearly, I need to do, at least, one followup to give you an even better idea of the range of these little wonders.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Microscopy

UK Front Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK