|

Surfaces: Part 2 - Specimens. by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

As some of you know, I am obsessed with invertebrate skeletal structures and whenever I get a new specimen, the first thing I do is examine its surface both for its structure and to see if there are any interesting critters which have attached themselves. This time, I want to look at the surfaces of some specimens and also the surfaces of some of their substructures. After all, all we every really see is surfaces according to some analytic philosophers, such as, H.H. Price (who was something of a minor loon). If we slice a tomato in half we are still just seeing a surface. But then as Cicero said: "There is no opinion so absurd but that some philosophy will express it." However, for my purposes here, we shall look at the surfaces of some things that are inside organisms or slices from structures inside organisms.

Let’s begin by looking at the shell of a heart cockle. The upper surface is delicately colored in pastels and has a lovely shape.

The under surface is also intriguing for it has a stark white background with greenish-gray splotches scattered around it. Cockles are a popular food in certain coastal areas. They are boiled and served with vinegar and pepper.

This next item is not edible, at least, not in its present form. It is a strip of native copper which has, as you can see, oxidized in vivid ways.

Next, back to the ocean. Starfish have 5 arms–right? Well, not all starfish. I have specimens with 4 arms and 18 arms and 24 arms. There are also some that might appear to have no arms at all. These are the cushion stars and below is an image of the upper surface of one.

However, if we turn it over and look at the underside, we see the five grooves for the tube feet and indeed we do have pentagonal symmetry.

Now, if we go back up to the image of the upper surface and look carefully, we can see 5 points where those grooves fold up over onto the top thus hinting at what we will find below.

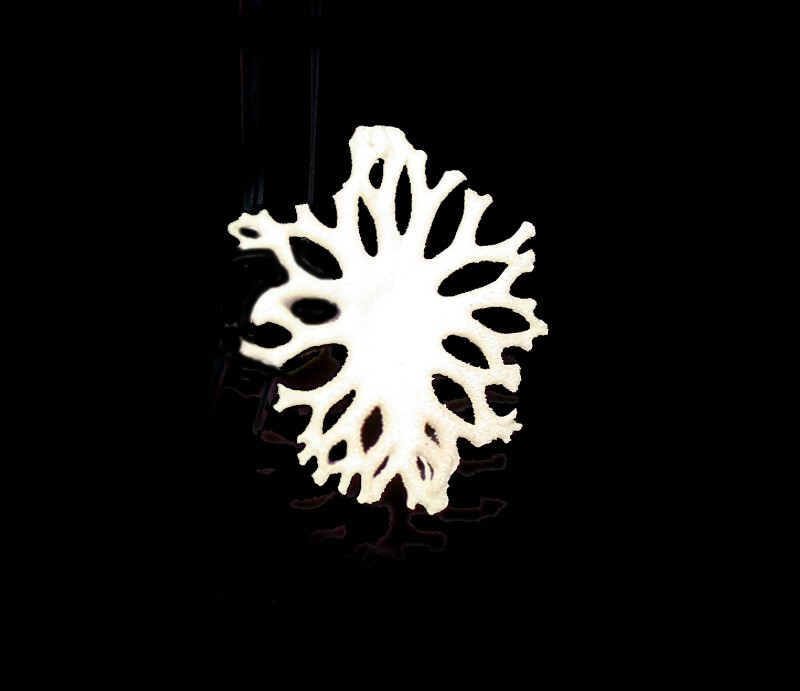

While we’re out wading around in tide pools, we remember that a bit of caution is called for because there are some very spiny relatives of starfish which, if stepped upon can cause a nasty puncture wound. These are, of course, sea urchins, although not all species have sharp spines and some have very eccentric spines indeed. I will show you an example from a tropical urchin Goniocidaris mikado. First, 5 spines, which lets you see them from several different angles. Definitely not your ordinary urchin spine! The top looks like a rather fanciful, if not very utilitarian umbrella and also intriguing is the ring around the base just above the round joint which fits into the socket thus forming the ball and joint structure that anchors the spine.

A top view shows us just what an unusual structure this is.

And, a view from the bottom reinforces that notion.

If you want some additional examples of weird sea urchins spines, you can find some real gems here:

Almost anyone who collects shells is tempted by the nautilus which is extraordinary not only in its outer appearance, but also because of its intricate internal symmetry which is very beautiful. Here is a view of the shell intact.

It has an almost otherworldly appearance and the organism which lives in this marvelous construction most certainly looks like an alien being.

You will notice that on that page, the title is “Chambered nautilus” which you might find somewhat puzzling if you have never seen the sections that have been cut revealing the internal structure which is simply amazing. Here is an image of one which has been sliced.

What is most striking is the beautiful spiral formed by the chambers. This is known as the Fibonacci spiral and is mathematically described as a logarithmic mapping of the numbers 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 etc. where beginning with 1, 1, all numbers afterwards are formed by the addition of the two previous numbers. This pattern has been argued to occur not only in the nautilus shell, but in everything from sunflowers to spiral nebulae. As the animal grows it adds new chambers by forming a septum which seals off the small chambers. One specimen which I acquired was sliced into 3 pieces and the center section shows the spiral very dramatically and also the siphuncles or ducts that link the chambers.

I also tried a little computer magic on this center section using the INVERT function in my graphics program and here is the result.

Next, we go from the Sublime to the Beauty Impaired.

This unlovely creature is a dried, wrinkled, freeze-dried nudibranch and it’s quite unfair to observe it in this pathetic condition. It belongs to the family Chromodoridae and here is a link showing you how vibrant and splendid they can be when living. In fact, nudibranchs are some of the most beautiful of all creatures on this planet.

So, you might well ask–why acquire such wretched remains as this shriveled thing? Well, morphologically it is still of interest even in this condition. Nudibranchs often munch on hydroids and manage to do this without triggering the nematocysts or stinging cells. However, they don’t digest them, they move them up through their own bodies into the cerata or dorsal projections and they then use them for their own defense. And these are of sufficient interest in themselves to isolate and examine them.

Another freeze-dried marine denizen is a small octopus and from this view we can readily understand why they are called cephalopods (head-foot).

Octopi are amazing contortionists and can move through spaces that seem impossible for them to navigate. The suckers on their feet (arms) are intriguing and are used for food capture among other things. Speaking of food, octopi have a sharp two-part chitinous beak which they use like scissors to rend food and fight off prey.

The suckers are very powerful and can hold prey firmly while the octopus attacks. Here is a closeup of some of the suckers on the arms.

Hidden inside many shells is another dimension of beauty which can only be discovered by slicing the shells into sections. These days such shell slices are produced in quantity and in wide variety. They are often found in craft stores and if you are ambitious and creative you can use them, along with lots of other tiny whole shells, to make Sailor’s Valentines which have a fascinating history which you can check out here and here.

I’ll show you a few sliced shells which I got recently and made a couple of small arrangements of.

Years ago, I cut some small shells by hand using a jeweler’s saw. It is very slow, tedious, and demanding work, but the results are pleasing. However, now you can get a packet of ready-sliced ones of 25 pieces for $3 or $4. Of course, they now use slick power tools with sharp blades and can do in a matter of seconds what it used to take me hours to do.

On the ocean bottoms, one can find small and medium-sized monsters. One such is the sea bat. This term is one which has been applied to a variety of unrelated creatures, but I’ll show you one which certainly fits the description; this is a small creature but quite fearsome looking.

Here is a closeup and it is, as you can see, quite spiky.

If we turn it over, we get another yet another view of the oddity of this little monster.

A closeup reveals books of gills that look rather like bellows.

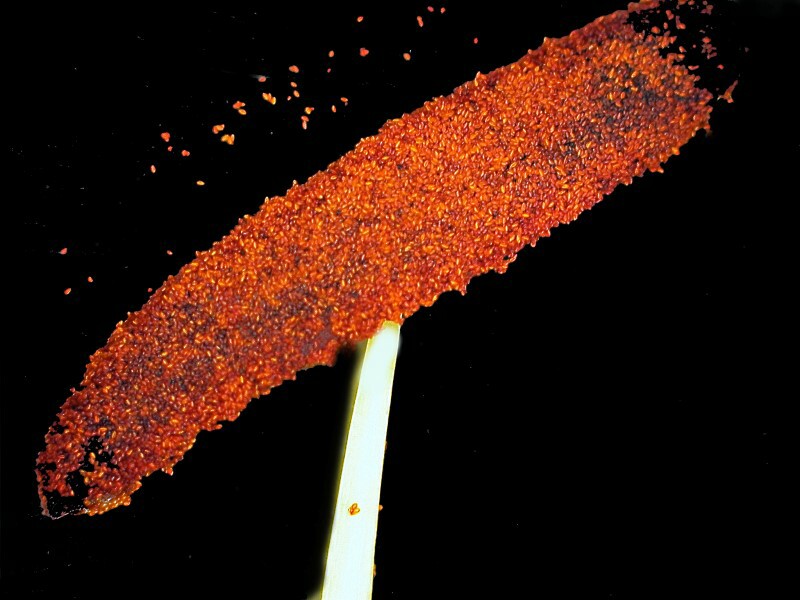

“Now”, as Monty Python says, “for something completely different.” As I was coming upstairs to my lab after lunch, I noticed that a couple of my flowers in a vase were shedding some bits and pieces, so I collected a couple of stamens one from an Alstroemeria or Peruvian lily and the other from a daisy. The pollen on the anther of the Alstroemeria is a brilliant red and looks quite festive.

The pollen on the anther of the curved stamen of the daisy is a rich yellow and makes me think of turmeric.

Well, I made it back up into my lab and found a potato. No, it’s a cucumber; well, it is a sea cucumber! It is a member of the family Stichopodidae and has a ring of 20 tentacles. It tends to live on soft sandy substrates.

And, you must admit, it does look a bit like a potato! The “bumps” on the surface have me curious and it looks like each one sits on a pentagonal area of tissue. This makes me want to start dissecting to see if perhaps there are some dermal or subdermal calcareous plates. But, for now, we’ll stick with the surface.

What we will look at next is highly curious, complex, and califragilisitic; it looks rather like someone dropped a small porcelain container that had some saffron in it. Amazingly, this structure has been known for over 2,000 years and was first described by Aristotle and so, is known as Aristotle’s lantern.

But why a lantern? Well, this was the first specimen of a group that I unwrapped and it fell apart in this interesting fashion. It permits us to see lots of intriguing detail including rows of striations and the tips of teeth? Teeth? Lanterns? Well, look at an intact specimen. First, a top view.

Then, a side view.

This incredible structure is the feeding mechanism of the sea urchin and usually consists of about 40 parts. Go back up to the broken one and you can clearly see the tips of the teeth. In the other views, you see structures which support muscles attached to the lantern structures and the teeth and move them allowing the urchin to scrape up algae and other detritus for food.

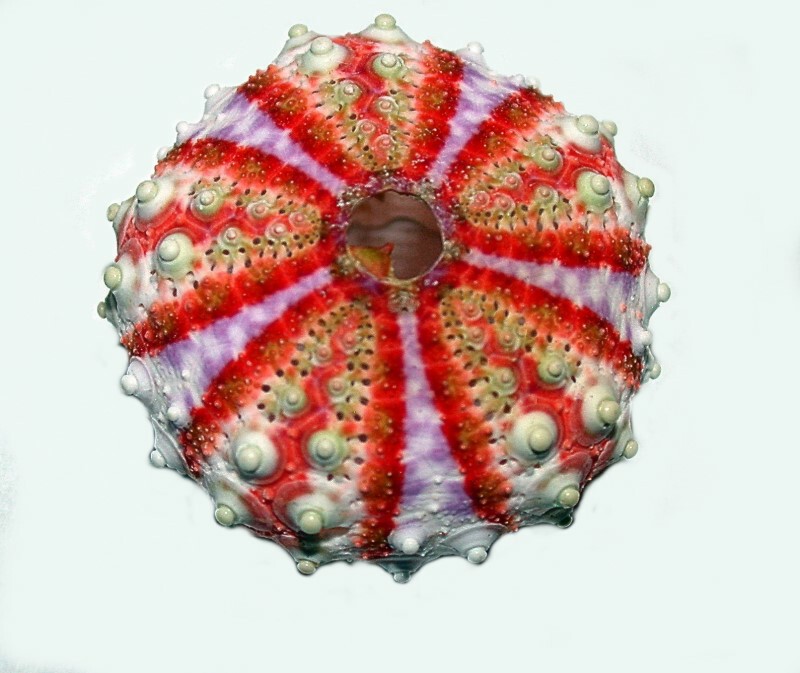

Finally a view of the “test” or shell of a small, lovely, brightly colored sea urchin, Coelopleurus maillardi. When still covered with its spines, you would be unlikely to guess what a magnificent pattern lies hidden below and so the removal of what constitutes one surface (the spines) reveals another surface (the test). All of which should teach us that a multiplicity of perspectives is necessary to even begin to understand the morphology and character of the natural objects which surround us.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the April 2016 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .