|

by Wayne Lanier, USA |

|

|

by Wayne Lanier, USA |

|

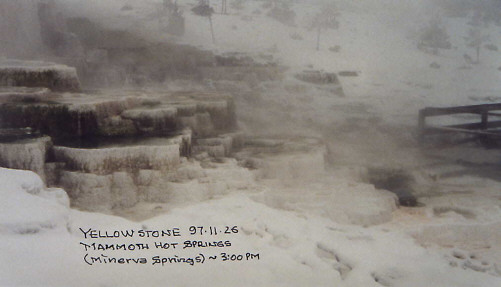

The first snowflakes were falling through the mists of Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park as I packed my field microscope and latched on my cross-country skis.

It was late afternoon in November of 1997 and some miles back to the truck parked near Yellowstone’s north entrance. The heavy winter snow had come and only a short stretch of the north highway was open.

Some folks hunt big game. I hunt small game. Very small game. With a Swift FM-31 I carry in my backpack.

The Swift field microscope is a compact inverted microscope with long focal length objectives. It is available in bright field, dark field, and phase contrast configurations. I started with a bright field configuration about 10-years ago, but recently retrofit to a phase contrast condenser and objectives. It has a simple micrometer-screw mechanical stage, a battery-powered light source, and camera adapter. It comes with a leather case for the microscope.

With achromatic parfocal lenses, the Swift is of quality comparable to the better student microscopes. It successfully combines both coarse and fine focus into one focusing mechanism. The mechanical stage has a spring caliper to hold a standard slide. The long focal length objectives make it unnecessary to invert the slide or to use special slides.

The Swift suffers from the problem all portable microscopes and many lab microscopes - insufficient lighting. On a bright, sunny day, this does not matter. Turning the top-mounted condenser toward the sun* provides excellent lighting for all high powers, even with phase contrast. On a dull day, or in the evening, photomicrography is difficult and observation at high power takes a little fiddling.

[* - Make sure your microscope is properly equipped to use the sun as a light source. Always use caution when looking at bright sunlight through a lens.]

The leather case is nice, but I do not use it. Instead, I use an impact plastic Pelican Mini S case that contains the microscope and small laboratory kit.

Fully loaded with microscope and pocket lab, it weighs about 4-lb. It is waterproof, lockable, and supposedly you can drive a truck over it without damaging the contents. In this case my microscope has survived airplane luggage handlers, falls, and grandchildren.

My pocket laboratory has changed over the years. Basically, you must have slides, cover slips, petroleum jelly, collecting vials, and a pipetter. At various times I have tried other tools, some were discarded and some have been useful. I replaced an eyedropper [useless] with an inexpensive pipetter that holds Pasteur pipettes. I have added a length of plastic tubing to extend the reach of the pipettes.

The interesting stuff in a sample is usually rare, tiny pebbles and silt are not rare. I have tried a small battery-powered centrifuge and filters. Both work, but I am not sure either is worth it.

I have faithfully carried a razor blade and forceps for years, but almost never used them. A 50-ml beaker, on the other hand, gets constant use. I never go out without a pocket full of small, screw-cap tubes for collecting. Plastic film cans will serve in a pinch. I carry neutral red vital stain, but rarely use it.

All field microscopes start as compromises.

The first compromise is portability, and it exacts a severe penalty. Compactness means a folded light path, adding prisms or mirrors to its design. A small turret means fewer objectives with nonstandard threads.

The second compromise is cost. I could write the specifications for a field microscope that would perform as well or better than most laboratory microscopes, but it would be far more expensive than the equivalent laboratory microscope. A specialty instrument with a small scale of production means high costs. Cutting this kind of cost always means reduction in performance. Lens quality suffers. The field is smaller. Magnification beyond 800X is a losing proposition.

So, is it worth it to have an extra, rather expensive, slightly inferior microscope for the field?

I think it is. Without a field microscope, I can only observe samples brought back to the laboratory. I could not have observed the thermophilic organisms in Yellowstone (taking wild life from national parks, even tiny wild life, is illegal without a special permit). Observation from any site more than a day away from my home would be sharply limited. Returning to the USA with a bag full of potential pathogenic fungi, non-native microbes, or just smelly pond water is likely to drive customs ballistic!

Rather than describe alternative portable microscopes, either antique or still available, I will direct you to the Microscopy UK Article Library and to Tony Saunders-Davies’ description of a home-modified Meopta portable microscope kit on the Quekett Microscopy Club website.

I was at Yellowstone because we were visiting relatives who live in Boseman, Montana. This web site says it all.

Yellowstone National Park is south of Boseman. I should confess that I have visited Yellowstone twice, but never in summer. If one is willing to ski in or to take the slow Canadian-designed ski-tractors, you can see Yellowstone in winter without the hoards of tourists that come in the summer. Many animals gather about the hot springs, geysers, and warm creeks that run from them. Geysers tend to be crowded, even in winter. It is much harder to take small samples for observation. The hot springs are the most fertile grounds for the field microscope.

Learn more about the thermophilic microorganisms of Yellowstone on the University of Edinburgh's web site.

Carrying a microscope around hot springs is a chancy proposition. Silicates in the steam can condense on cold lenses very quickly, giving the lens a new shape, permanently. There are restrictions about climbing off the wood walkways built to keep tourists from damaging the ecology around the springs. Be prepared to take samples while lying flat on the wet walkway. This is where the long Pasteur pipettes and extension tubing came in handy.

I did not take photomicrographs at Mammoth Hot Springs. At that time I did not have the camera adapter. Until recently, all my records were in the form of notes and drawings in my field notebook. Below are some examples:

Field microscopy is, for me, an integral part of the wildlife and geology of an area. My notebooks are filled with sketches of plants, rock formations, and morning skies. I carry a pocket camera for the chance animal that strolls by.

Geology is a major show at Yellowstone. I highly recommend Fritz, W. J. (1985) Roadside Geology of the Yellowstone Country, Roadside Geology Series, Mountain Press Pub. Co., Missoula, MT. The Roadside Geology Series covers the western states well, and even some of the eastern states.

Skipping some 2,700-million years, the excitement started around 2-million years ago with a volcanic eruption that blasted 600 cubic miles of ash and rock across the American continent and created the first Yellowstone caldera. A second and much more modest volcanic explosion followed (at 47 cubic miles, it was only about 10-times bigger than Krakatoa). The third volcanic explosion, around 600-thousand years ago, created the present Yellowstone caldera and blasted out another 240 cubic miles of ash and rock. It has been relatively quiet since then. The hot springs and geysers are driven by hot magma bubbling around down below.

Mammoth Hot Springs is in the northwest corner of Yellowstone. It spent the last ice age buried under nearly a mile of ice. It is at the tip of the Absaroka lava flow in the Western Absaroka Mountains. It is cool for a hot spring, around 167-degF. Most of the mineral deposited by the hot spring is in banded layers of limestone, called "travertine". You can see the travertine deposits in the title photograph.

Sierra Pole Creek

To show photomicrographs with the Swift microscope, we skip ahead to May of 2001. Here, also, hiking with a microscope is more a naturalist’s experience. The Tahoe National Forest sign read” “You are a part of the plan.”

About 6-miles from the California town of Truckee, in the Sierra Navada, Pole Creek runs down out of the mountains to join the Truckee River. The Truckee River drains Lake Tahoe. Twelve-thousand years ago Lake Tahoe and the Truckee River were part of a glacier system flowing out of the Sierra Mountains. By now you may have guessed there is a Northern California Roadside Geology.

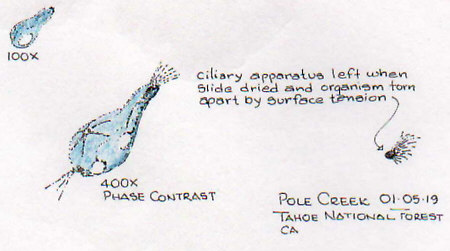

The night before I had sampled Pole Creek near the Truckee River, bagging an unidentified protozoan [shown in a drawing from my notebook and in a photomicrograph].

I was on my way to the High Meadow, up a logging trail parallel to Pole Creek and on the way to Silver Peak. I have been visiting the High Meadow for several year, following the seasonal changes in its normally enormous colonies of Paramecium bursaria.

Two Teal [male ducks] at image centreSix-weeks earlier the high meadow had been frozen under more than 6-feet of snow. Now it was a wetlands marsh, sporting two Teal, probably resting on the way north. Along the border of the meadow, Snow Plants were popping up…

Native to the Sierra Mountains, these saprophytes

come up as the snow meltsAnd the delicate blossoms of Manzanita, another California native.

My GPS read that I was at 6,259-ft. My backpack holds the impact plastic camera case with microscope field kit, a Canon 35mm camera, GPS, compass. The pocket laboratory is housed in a aluminum lunch box, bought in San Francisco’s Chinatown, which fits in the case. I use a hiking cane made from a Louisiana Frog Gig.

I wear boat moccasins with Vibram soles so I can get my shoes wet, yet have the traction and support for hiking. In California and the desert I always wear long pants, since hiking in shorts invites poison oak rash.

I use both brightfield and phase contrast. At first I was uncertain about the extra expense of the phase contrast system, but I have come to appreciate it more and more. An important addition was a 20X eyepiece. The microscope 3-place turret only has 4X, 10X, and 40X objective lenses. Adding the 20X eyepiece increases the range to include 40X, 100X, 200X, 400X, and 800X.

While I was setting up a grass snake swam by the marshy border of the meadow.

Snake at image centreBy the end of June this “lake” will have dried up to a few small spots of damp mud in a thick grass meadow. By August it will be sparse brown grass over cracked dry mud flats.

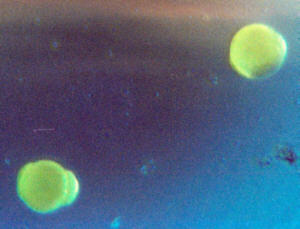

My first sample picked up diatoms, water mold spores, a Volvox-like critter that is probably Gomphospheria, and some nematodes. I did not see any of the paramecium I had come looking for. In previous springs, I had encountered many paramecia stuffed with Chlorella cells. Apparently they enter into a symbiotic agreement with the alga cells, but towards fall the paramecia cancel the agreement and digest the Chlorella. The only Chlorella cells I saw this time were inside a nematode.

You can compare photomicrographs made at the site with my drawings. Setting up for photomicrography takes about as much time as drawing, and I prefer the drawings. I am rarely pleased with my photomicrography in the field.

In a second sample, further up the mud flat, I found some lovely chains of Anabaena, and a gelatinous mass of Nostoc.

I have taken this field kit all over the Western United States and to Europe [England and Austria]. If I go on a weekend day hike, my microscope goes with me. In fact, if I only had one microscope, I would probably spend quite a bit to make it portable.

How to contact me. If you visit San Francisco, let me know.

I live in San Francisco. If you are planning a visit and have time for a field trip, let me know. I am always happy to take visitors out to the local tide pools, salt marshes, or wetlands.

My thanks to Dr. Vojtech Licko, who scanned many of the photographs into electronic jpeg images.

All comments to the author Wayne Lanier Ph.D are welcomed.

Please report any Web problems or offer general

comments to the

Micscape

Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK