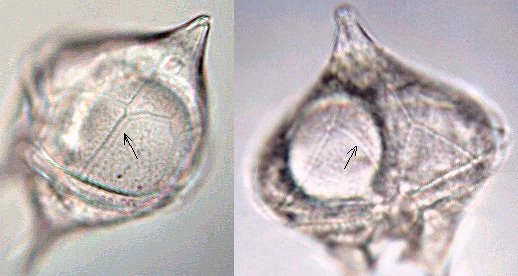

I have witnessed a serious bloom along the southern coast of France, but it wasn't visible except by microscopic observation. The guilty party was a species of dinoflagellate called Alexandrium tamarense, with a size around 20 µm. This organism produces a toxin (domoic acid or PSP : Paralyzing Shellfish Poisoning) which is poisonous for man and paralyzes the nervous system. Toxin is concentrated by filter feeding molluscs which are immunized against it and they became unsuitable for eating. In 1998 the bloom occured in October which was unusually late in the year. Many mussels and oyster breeders were very annoyed, because they didn't sell their products during the two months leading up to Christmas and the New Year.

Note the two rounded chromatophores in the top right hand side image.

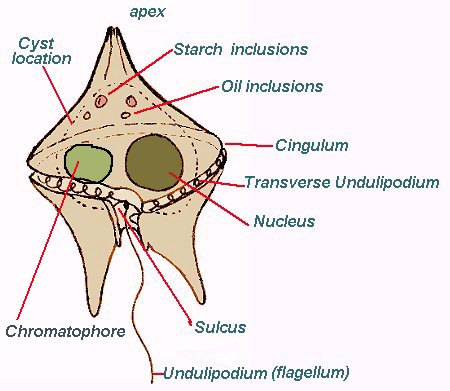

At first sight, to an inexperienced observer, critters which are quickly moving under a coverslip are 'necessarily' animals, mainly those which cross the field of view like tiny torpedoes! But if you can see a flagella whirling behind its body it's possibly a dinoflagellate. See schematic drawing below.