Zoologically speaking, true worms or annelids are segmented. There are a number of small phyla which contain worm-like organisms that are not segmented, but most of them don’t possess weapons, rather they depend largely upon defensive strategies to avoid predators. However, a notable exception is the nematodes and this is a large group of diverse creatures with some extraordinarily interesting characteristics. There is an important group that preys upon plant roots. Their weapon is called a stylet and is like a microscopic hypodermic needle. They puncture cell walls and feed on the contents. They can be found in the watery coatings around plant roots or even live within the root itself. If you think that’s amazing then, hang on, and consider the carnivorous fungi that feed on nematodes. This is a strange and distinctive group which has evolved a variety of techniques for trapping nematodes including various sorts of sticky substances, sometimes rather like webs and, most intriguing to me, tiny rings which once the nematode is moving through them are capable of constriction. Here’s a link to Google showing some of the types of nematodes.

There is one of these worm-like creatures that is of special interest, Caenorhabditis elegans (hereafter C. elegans). This organism has been singled out as a model research critter for some special reasons and has proved to be a source of large amounts of important and promising information. It is one of the most primitive organisms with a nervous system and the patterns of its structure have been virtually completely mapped. It is a lesson to us as to how complex “primitive” organisms can be. C. elegans displays responses to reagents, heat, mechanical stimulation and is capable of learning and remembering. There are hermaphroditic as well as male and female forms. Its various stages of development have been completely mapped at the cellular level.

It has shown resistance to radiation and has been sent into space to further study its reactions. On a terrestrial level, it has been used to study nicotine addiction. So, we are beginning to get an idea of the remarkable potential of C. elegans.

And finally, as a tour de force, C. elegans has been used to study ageing and telemeres, sleep (yes, remarkably it has somnolent periods), Alzheimer’s, and even light sensitivity; it doesn’t have eyes, but it does possess a light-sensitive protein.

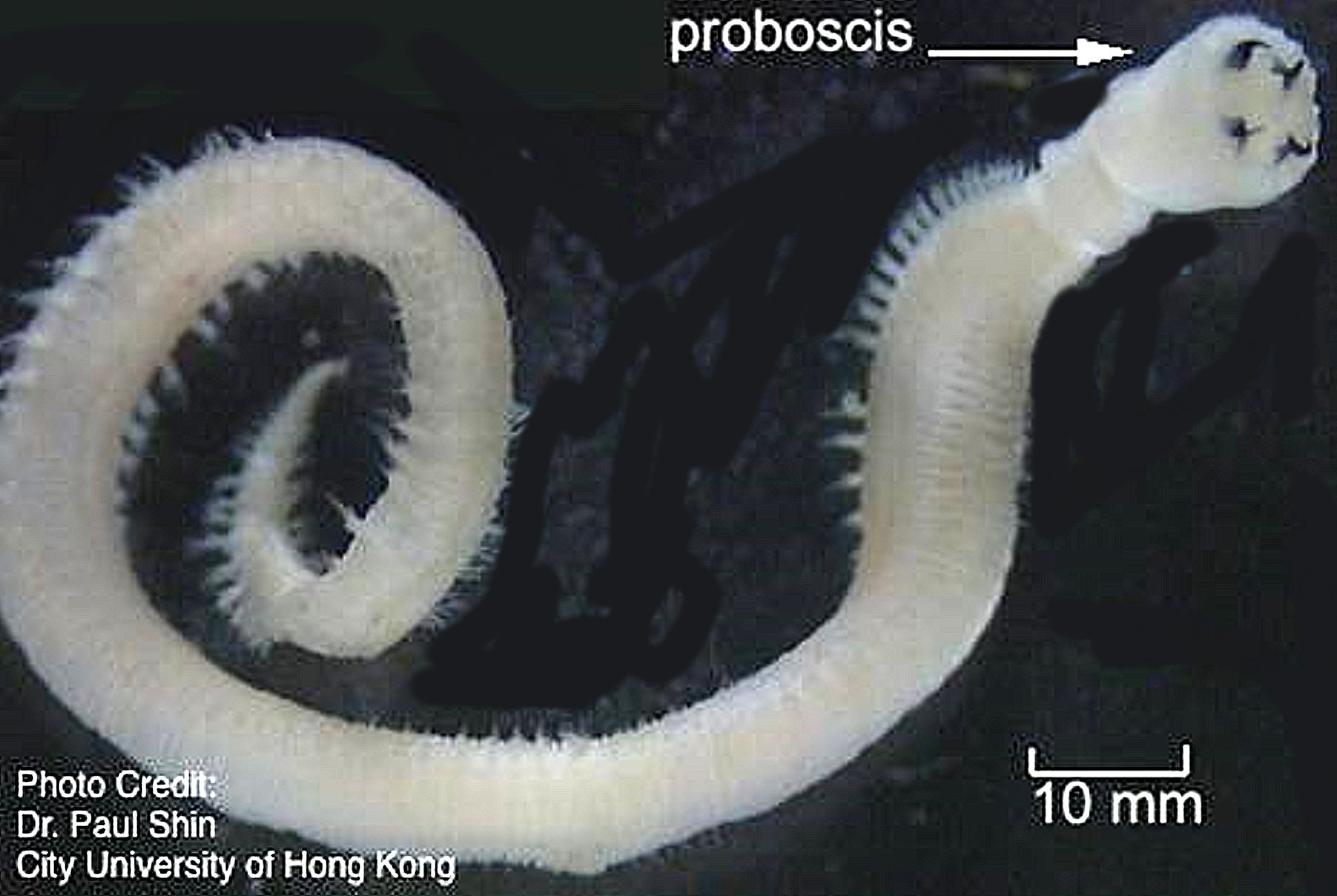

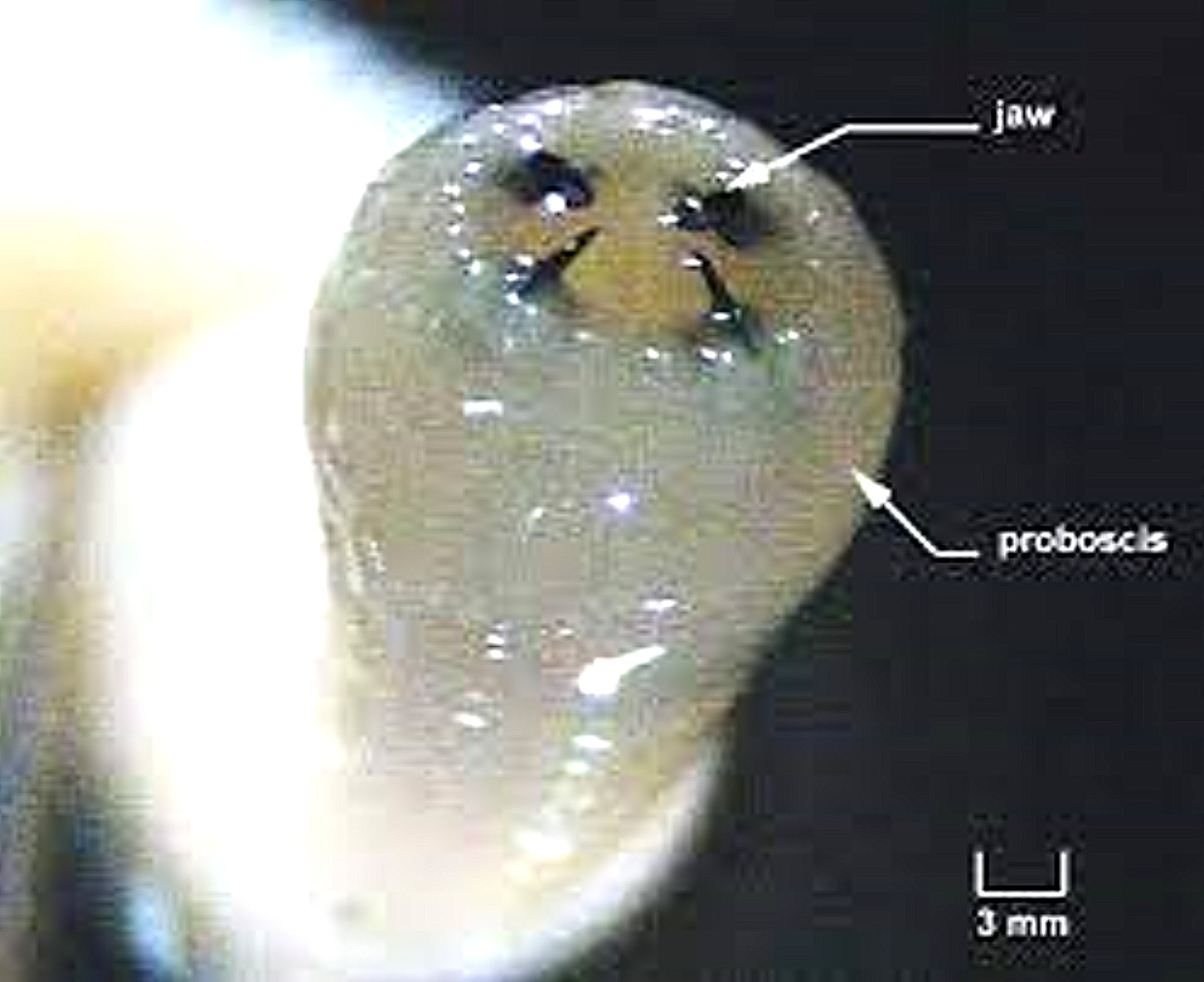

Moving on to the annelids or segmented worms, I will give you a couple of examples. As it turns out, this will be one of my shortest essays of all times, for two reasons: 1) it seems that annelids have relatively few weapons and 2) relatively little research has been done on any toxins or structures other than a few which I will mention. A rather intriguing example is the so-called “beak-thrower”, Glycera, also known as a bloodworm. It is able to evert its proboscis at a rapid rate and capture prey with its four poisonous fangs or jaws. I’ll show you two images from Google; the first is a view of the whole worm and the second is a closeup of the proboscis showing the jaws.

Some of the polychaetes, such as, Nereis can get up to a foot long and can burrow with unbelievable speed. One summer, on the coast of Maine, I went one day to an area of mudflats when the tide was out. I had a shovel to see what wonders lay buried in this special environment. I turned over lots of worms, many bright red, some a lovely blue and gold. However, when I tried to collect them, cautiously because they looked rather like they could deliver a painful nip, they would disappear before I could get them into a bucket. After several futile efforts, I managed to collect 3 or 4 and felt exhausted from the effort. I learned that my caution was indeed worthy, as you will see from two closeups (SEM) of the jaws of these burrowing polychaetes.

This is the stuff that nightmares are made of. Let me show you one more; here are two images of the “Bobbit worm” which is known for its unpleasant “bite” and an accompanying toxin to round off the fun. Notice how the jaws are spread in a welcoming fashion.

These types of polychaetes have jaws whose teeth are composed of chitin.

Although this was a very brief tour, I hope it gave you at least a glimpse of another dimension into invertebrate weapons.

In the next installment, we’ll begin looking at Arthropods, starting with caterpillars of butterflies and moths.