We’ve been discussing calcareous material and structures in marine invertebrates but, so far, have only touched on the asteroids or starfish (sea stars), all of the names being misnomers, if you want to get picky about it. Asteroids are one of the greatest violations of pentagonal symmetry along with crinoids, comatulids, and some irregular echinoids. Some starfish rarely have only 5 arms and some have over 30. Nature just loves to mess up our attempts to classify and put things in neat order.

The amount of calcareous material in a starfish is, in general, relatively high. In some species, it’s clearly visible as spines, whereas in others, it’s largely subdermal and so only barely visible, if at all, as is the case with the so-called leather stars (and no, this doesn’t have anything to do with the famous Hell’s Angels). But, let’s start with a showy spine kind.

Just take a look at this chap with abundant protruding red spines. This is a specimen of Protoreaster lincki.

In the process of drying and preserving such specimens, the color is often greatly diminished or even lost completely. This one is a rather pale version of the living organism, so, I’ll provide a link to a photograph of a living specimen–spectacular!

We can hope that with all of this captured carbonate that these critters are trying to help us out in terms of saving the planet from global warming and radical climate change.

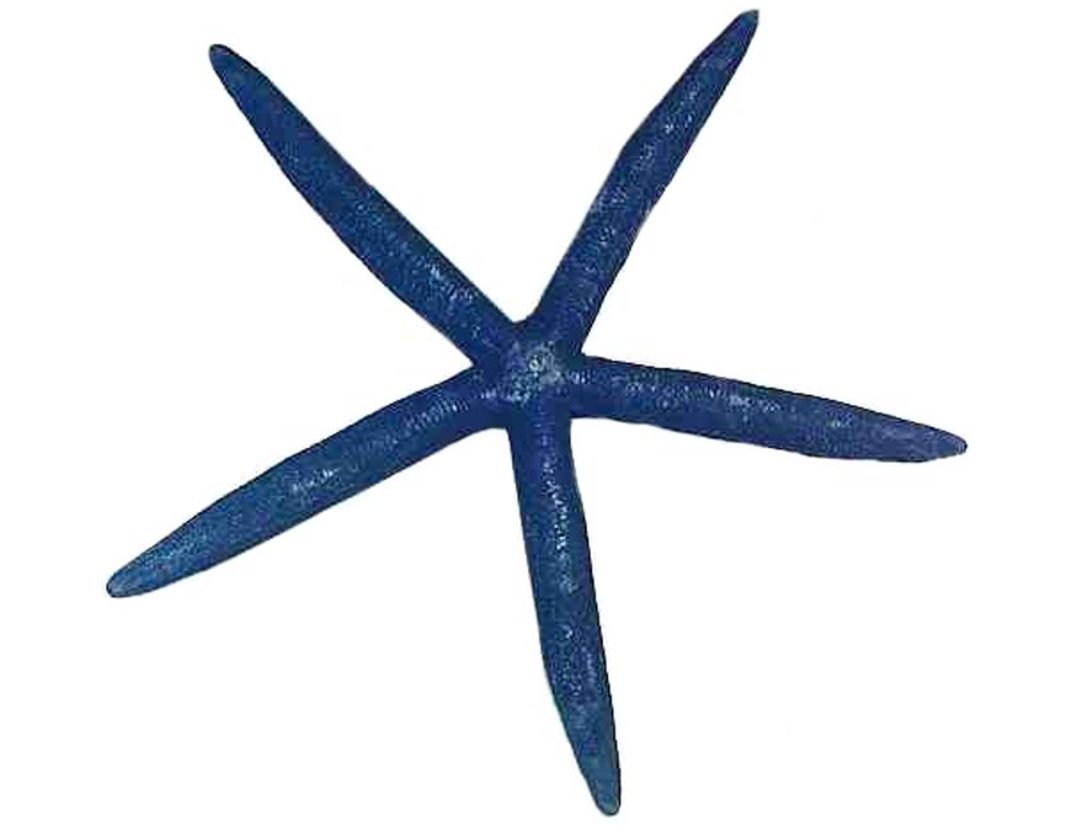

A starfish which does keep its color quite well when dried is the blue Linckia.

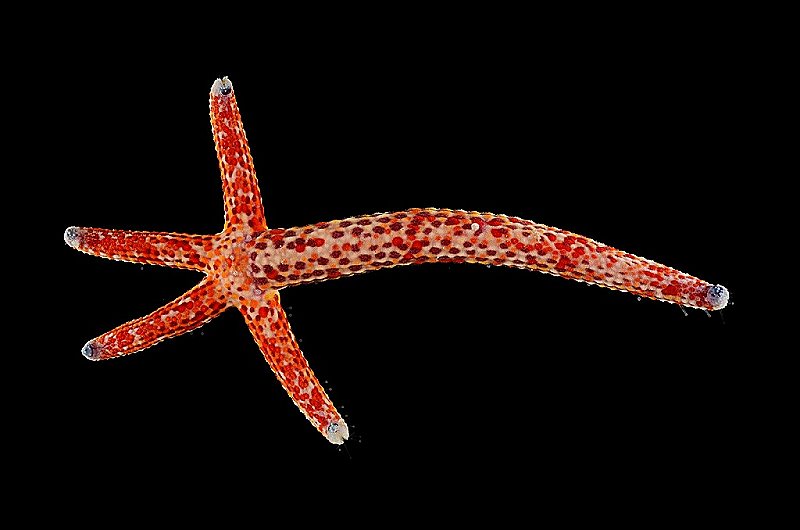

Some species of this organism are also known for their extraordinary ability to regenerate as you can see here.

The calcareous material in this genus is not immediately evident as it is in the Protoreaster which we looked at above. However, if you cut sections and dissolve the tissue using Sodium hydroxide or household bleach, which is mostly Sodium hypochlorite, you will find an abundance of small calcareous structures.

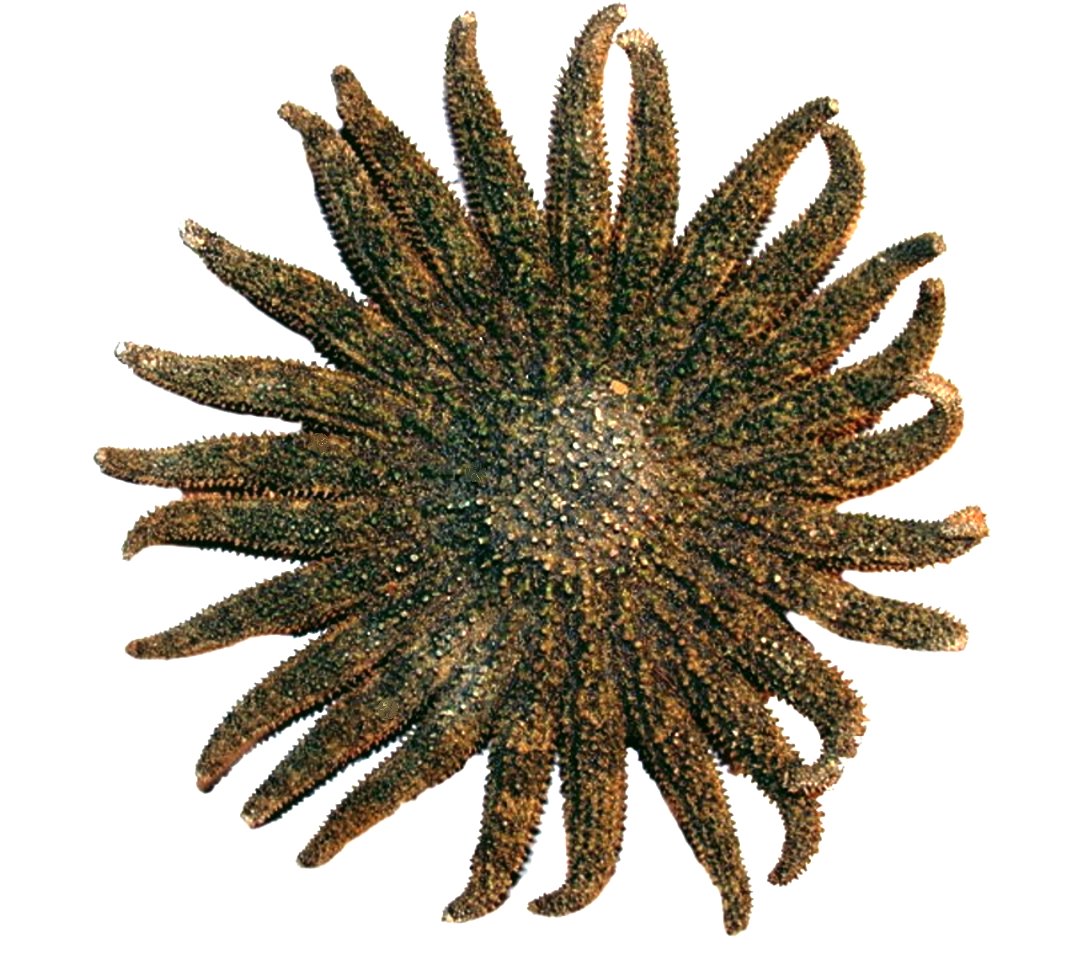

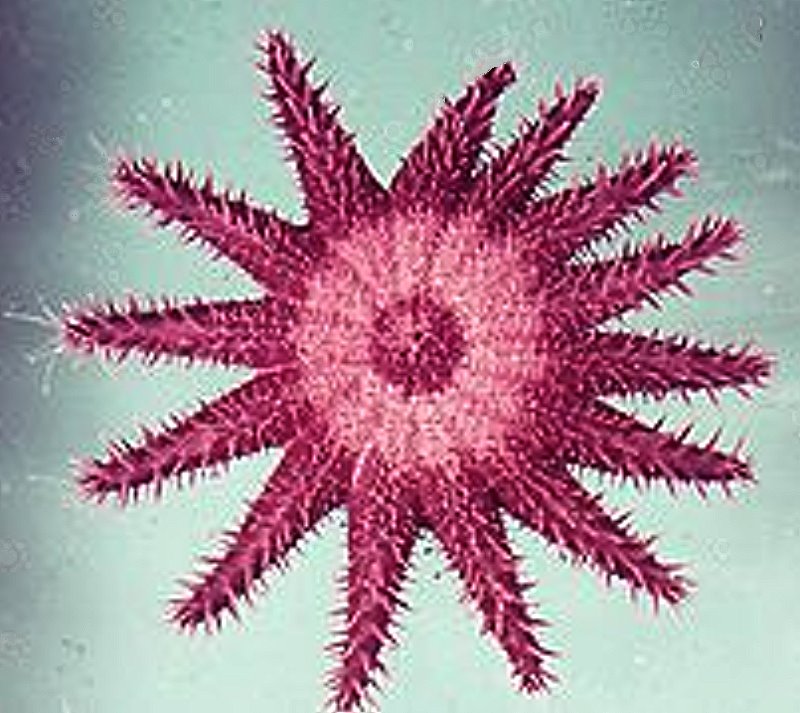

As I mentioned above, some starfish are well-armed and Heliaster is a marvelous example. It usually has from 25 to 50 arms in which there is an abundance of calcareous ossicles. This is a large organism and typically has a diameter of up to 10 inches.

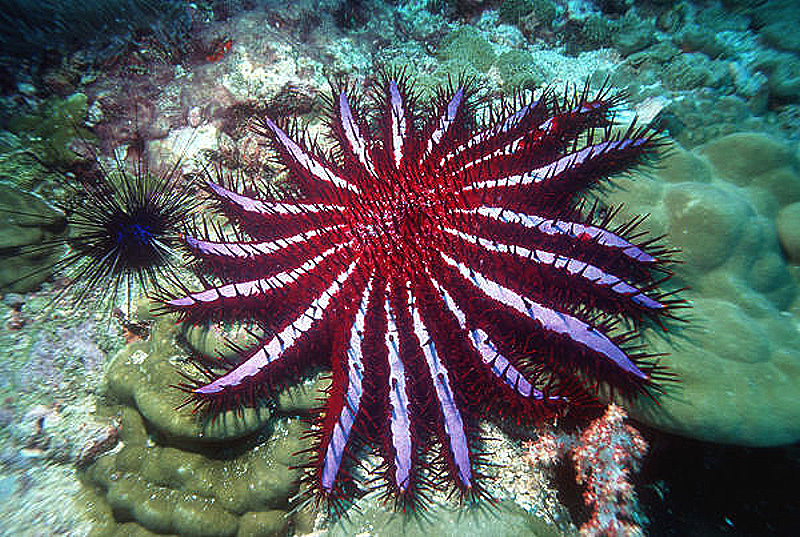

Another large asteroid is Acanthaster or the notorious “Crown of Thorns”. These are “beautiful monsters”; they’re often very brightly colored in striking patterns, can be up to about 15 inches in diameter and have around 20 arms. Why are they monsters? They are ravenous coral eaters and not only devour the polyps, but remove considerable chunks of the calcareous structures in which the polyps reside. So, they have lots of spines, thus lots of calcareous material, plus they ingest calcareous material as well. These abundant spines are capable of delivering a toxin which is highly irritating and potentially dangerous. These starfish are significant contributors to the destruction of sub-tropical reefs and notably parts of the Great Barrier Reef. They can’t be poisoned, because that would also drastically affect the health of the corals. Because of their toxin, divers have to exercise great care in prying them loose and must protect their hands and skin. Once removed, the starfish have to be raised overhead to a boat for disposal. They cannot be simply chopped up and the pieces thrown back in, because these are organisms that can regenerate from a portion of the central disk and an arm or two. In the photographs below from Google, you can get an idea of the variation and beauty of this strange and destructive critter.

Starfish show immense variety in terms of the number of arms, size, color, texture, and patterning. Let’s look at a few more examples of pattern diversity, again from Google.

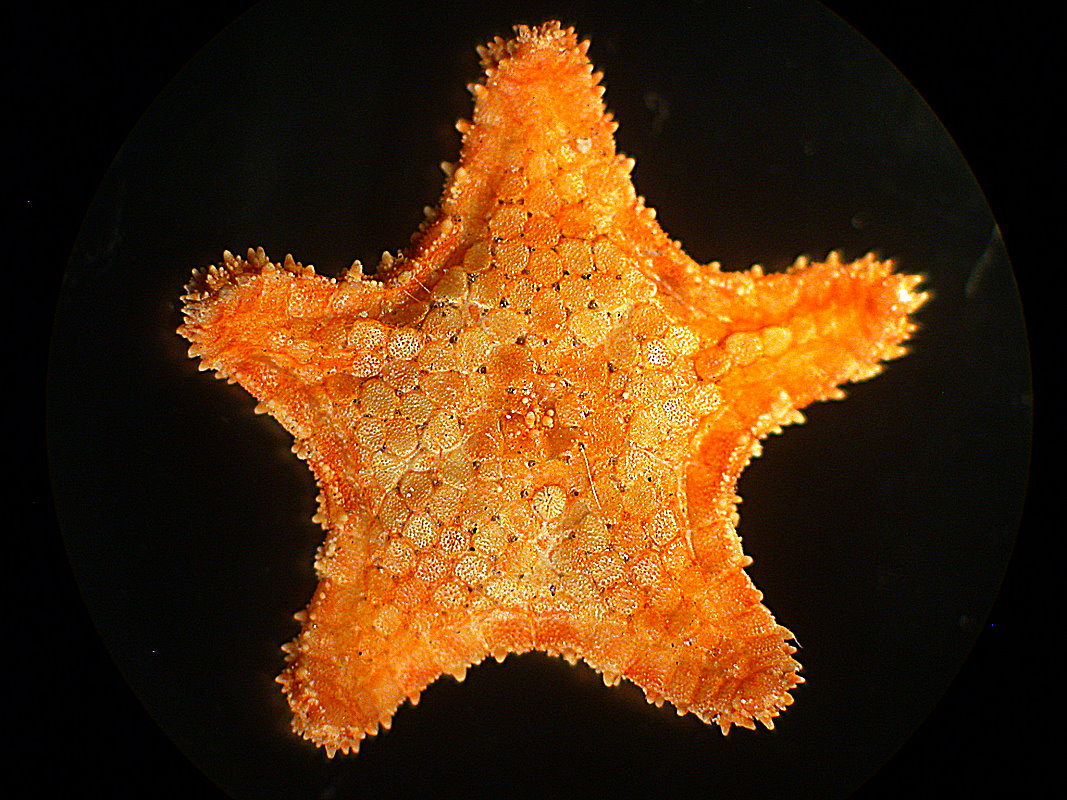

This last image is of a cushion star and illustrates not only diversity of form, but of texture as well. Here on the central “disk” and around the edges, you can see calcareous “plates” which indicate that this is a calcium heavy critter. Such a crunchy exterior discourages predators and also creates an intriguing puzzle for us poor ignorant humans–why would a creature form a square, armored shape of such wonderful patterns and intricacy? A bit later on, we’ll look at some other examples of tessellation, the covering of a surface with one or more geometric shapes without gaps or overlaps. Mother Nature subjecting us to her clever tricks once again! “Devious Mother Nature”–good name for a rock band.

Next, I want us to take a look at another rather strange starfish, the “leather star”, Dermasterias. No, it doesn’t hang out in aquatic leather bars or ride a motorcycle, but it does smell sulphurous.

This organism is interesting because the odor probably is a deterrent to some predators (however, not the sun star, Solaster, which seems to relish Dermasterias.) The leather star is smooth and slightly slippery as a consequence of a mucous which it secretes. It can get up to about 12 inches in diameter. It doesn’t have spines or pedicellariae (those little pincer-like structures that echinoderms use to keep opportunistic micro-critters from settling on their surface). The only noticeable calcareous structure is the madreporite on the upper surface of the disk. This is the structure that acts as a “filter” for the water that enters to control the vascular system that operates the tube feet. In the image above, you can see it just to the left of center; it is the yellow circle. The smaller such circle, to the right, is the anal pore.

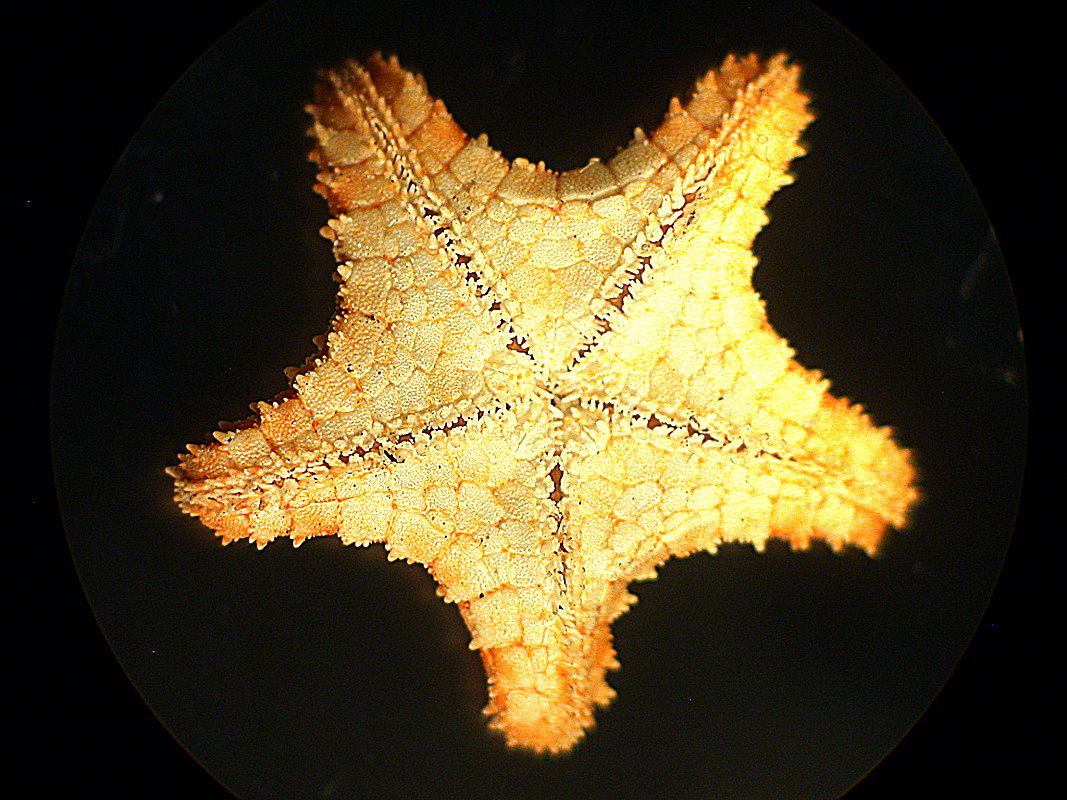

Sometimes, collectors and hobbyists who want specimens for display get frustrated by the difficulty of finding “perfect” examples. In part, this is due to a desire for large showy specimens. Often older creatures, which tend to be larger, show the scars of survival, of having fended off predators or they may have lost an arm or two and are still regenerating or have regenerated a deformed replacement. Some of the most “perfect” specimens are quite small and thus not showy, but are ideal for the macrophotographer. I’ll show you images of 2 small specimens which I got from the Philippines and I mean small; the first one is about 3/4 of an inch in diameter and the second is about one inch. For each, I’ll show you the aboral view and then the oral view.

This is a very nice specimen with clear, undamaged surfaces and we can see the tiny spines, especially around the edges.

This one was not so fortunate and you can see some scrapes on the aboral surface. When there is damage to specimens, one can often not be sure when it occurred naturally or as a consequence of the preserving and drying process or rough handling or poor packing for shipment.

Others live in bays where there is little tidal action and few currents and, as a consequence, there may be a nearly constant rain of detritus down onto them. This spiny little specimen shows how the surface can be almost constantly covered with such debris.

Even the oral side shows scattered detritus and it is likely that the starfish screens it for food particles.

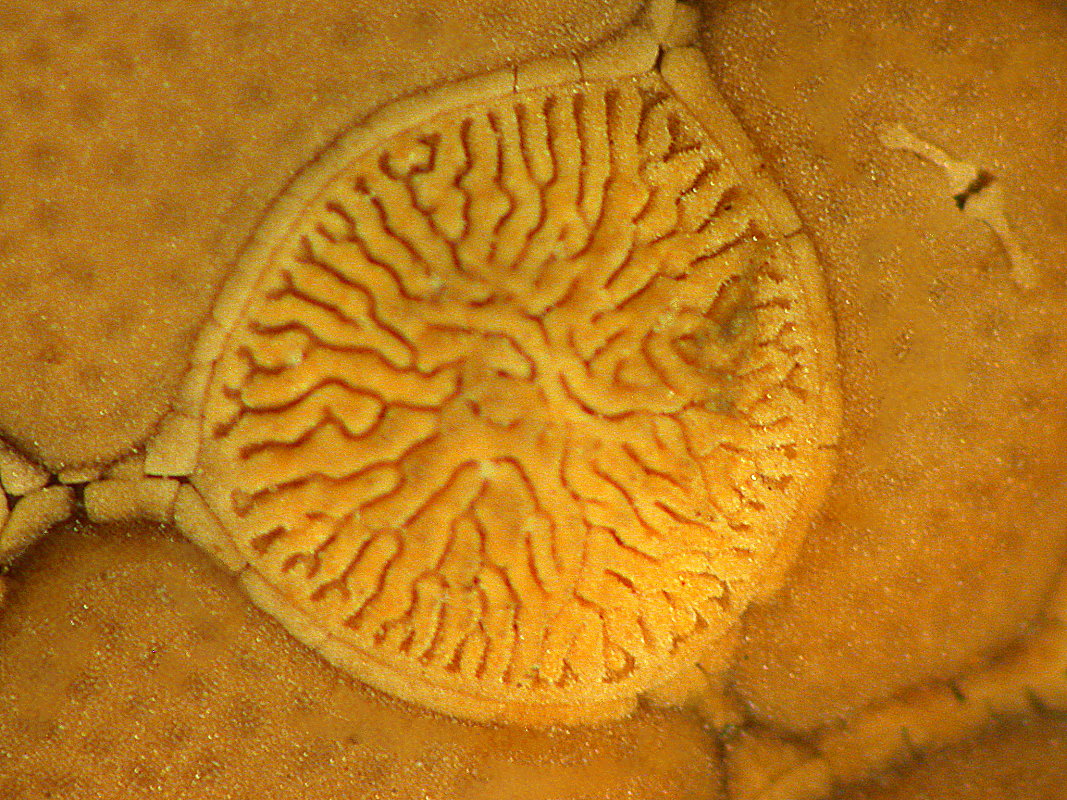

At this point, I would like to leapfrog back to another example of a quite unusually shaped asteroid that certainly, at first glance, one would not think of as a starfish. This is the cushion starfish, Culcita.

This is the oral view and you can readily see the pentagonal symmetry.

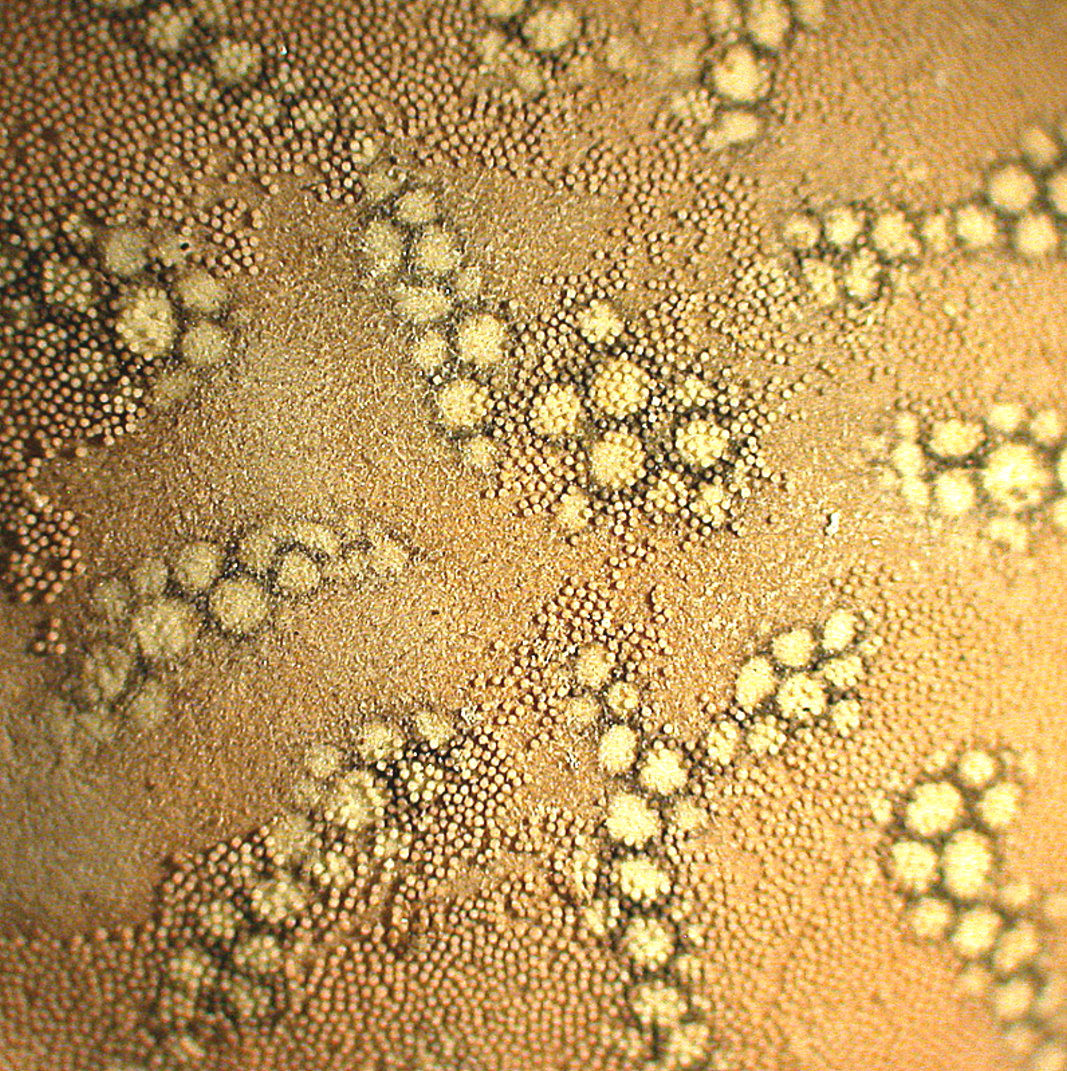

If we take a closeup of the surface, we can see clusters of small, spherical calcareous nodules.

I mentioned earlier that wonderfully clever device of tessellation and I would like now to show you another example or two or three from the surface of a small starfish.

This first image is at the center of the disk.

The next image is of one of the arms which shows the patterning both in the central part and also along the edge. In the upper left, you can see the madreporite.

Here is a closeup of the madreporite and off to the upper left you can see an odd little wing-like form.

This wing-like form is a puzzle. I have no idea what it is and could find no reference to it which, of course, makes it all the more intriguing. Here you can see a scattering of them around the surface.

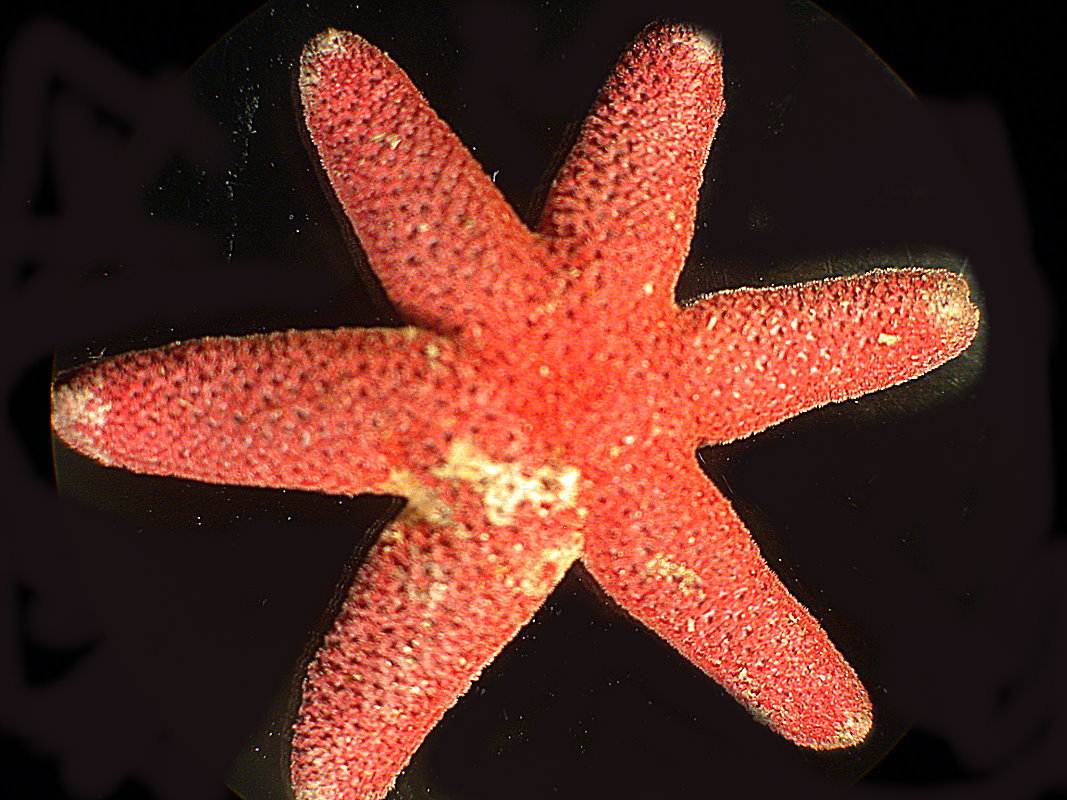

To move toward the end, it’s time to expand our area a bit and take a brief look at the ophiuroids or “brittle stars”. These are amazing creatures and they can move very rapidly with what some have described as a snake-like motion and the Greek for “snake-like” is “ophio-”. With shifts in ice mass in the Antarctic, areas of the sea bed have been discovered which are “gardens” of brittle stars. Here I want to show you 3 different specimens from the Philippines and then we’ll take a close look at one of them. When dried they are quite fragile, because they are after all “brittle”, so some of them are missing parts. This first chap is modestly colorful and banded in interesting ways. No spines along the arms or surface are visible in the view as they are quite small.

The next specimen is somewhat small and clearly needs to shave his or her legs. Some brittle stars have quite long spines that can be of help taxonomically.

The third specimen is the one which we will want to take some close looks at. It is sizeable and distinctly marked as we shall see when we start to look at it up close. This is an oral view of the whole organism and we can see that the madreporite is on the oral surface as we’ll see in the first closeup.

Next we have a close up view of the aboral surface where the spines are clearly visible and on the surface of the disk we have a “Kilroy Was Here” cartoon.

The small structures vary enormously in echinoderms and here in the ophiuroids, we can see some interesting contrasts even to those micro-structures in the asteroids. First, let’s take a look at the central part of the oral disk of a specimen.

In this particular species, the calcareous arrays tend to be small spheres, curved plates, or blunt spines. In the view below, you can see all three.

Obviously, we have barely scratched the surface when it comes to the marvelous intricacies in these wonderfully mysterious animals, but this essay is already a bit too long, so further examination is up to you or you can wait for me to get around to a sequel, but with all my other projects, that may take quiet a while. In any case, keep looking at all the wonderful creations of nature which surround us and hope that they will teach us how to adapt better to our only home, planet Earth.

All comments to the author Richard Howey

are

welcomed.

If email software is not linked to a browser, right click above link and use the copy email address feature to manually transfer.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the October 2021 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .