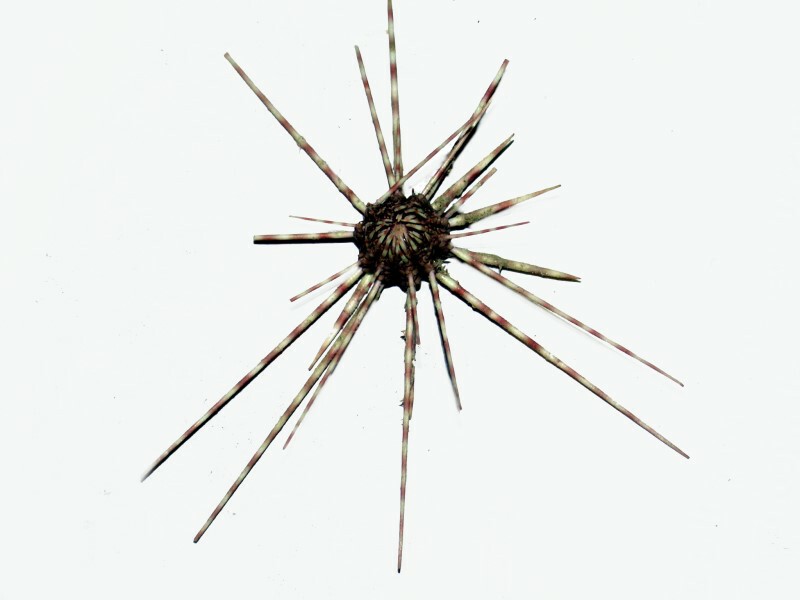

In Part 1, I mentioned sea urchins so, let’s look at a few which I have on display. One of the many special delights of echinoids is that when they are nude they are often strikingly attractive, unlike most human beings. I’ll show you an example: first, the urchin with its spines and then the same species denuded.

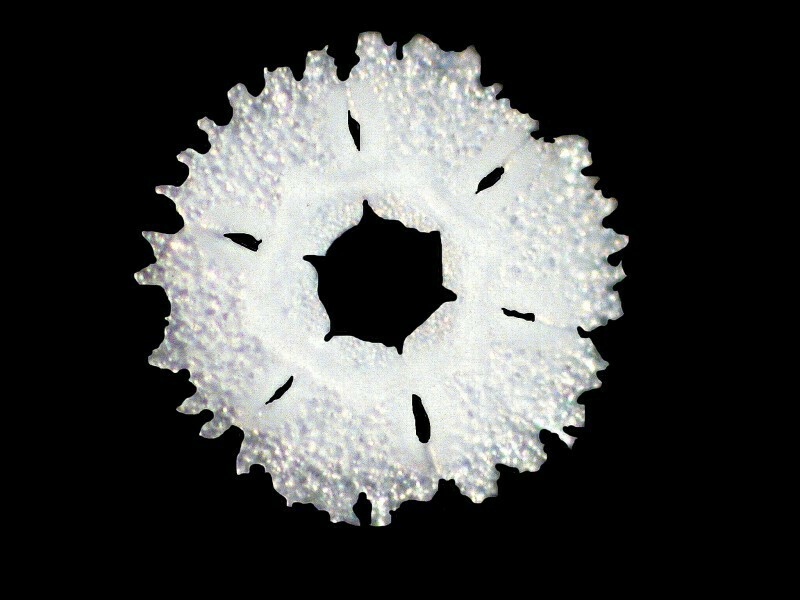

If you want to build up a collection of these marvelous creatures’ “skeletons”, here is an excuse to indulge yourself in purchasing 3 specimens of each species (price permitting, of course). Shop around on the Internet, for some dealers charge exorbitant prices for specimens which you can find much more reasonably elsewhere. So, if you acquire 3, you can display one, complete with spines, a second one with the spines removed, and then you can outrageously vandalize the third one by taking it apart bit by bit to discover its splendid architecture and in some species, even in the case of dried specimens, you can reveal such bizarre features as elegant calcareous plates in the pits of the tube feet or see in the stalk the “jaw-like” structures of the pedicellariae hiding down under the spines near the surface of the test or “shell.” Below is an image of a tube foot plate.

And here is an image of pedicellaria which is a remarkable defender of the surface of the urchin since its jaws can grasp and crush larvae of other organisms that are trying to establish territory on the urchin.

There are 2 basic groupings of echinoids: the regular and the irregular. (Don’t’ you wish that all of our classification criteria were so clear and straightforward.) The regular urchins are the spiny ones that you usually think about as something you don’t want to step on in bare feet. The irregular urchins are generally flattened and have an enormous number of very small, thin spines. This is the group that contains sand dollars and their relatives, such as, sea cookies, sea biscuits and heart urchins. I’ll show you a few standard types of both regular and irregular echinoids from my cabinet.

Let’s start with some possibly familiar examples of regular urchins.

1) Strongylocentrotus purpuratus which is quite common in U.S. West Coast areas.

2) A large tropical “slate pencil” urchin which also has an intimidating scientific name–Heterocentrotus mammillatus.

3) Now, we’ll move on to some more unusual types beginning with an urchin with very strange spines. This is Psychocidaris.

4) Another one with bizarre spines which look rather like inverted umbrellas is Goniocidaris clypeata.

5) And then there is the well-known “Sputnik” urchin, Phyllacantus.

6) A fascinating and beautiful group of small urchins is the genus Coelopleurus. I’ll show you one with spines and then the test of C. exquisitus, a specimen dredged off New Caledonia.

7) Another urchin with a strikingly colorful test is Stereocidaris grandis rubra.

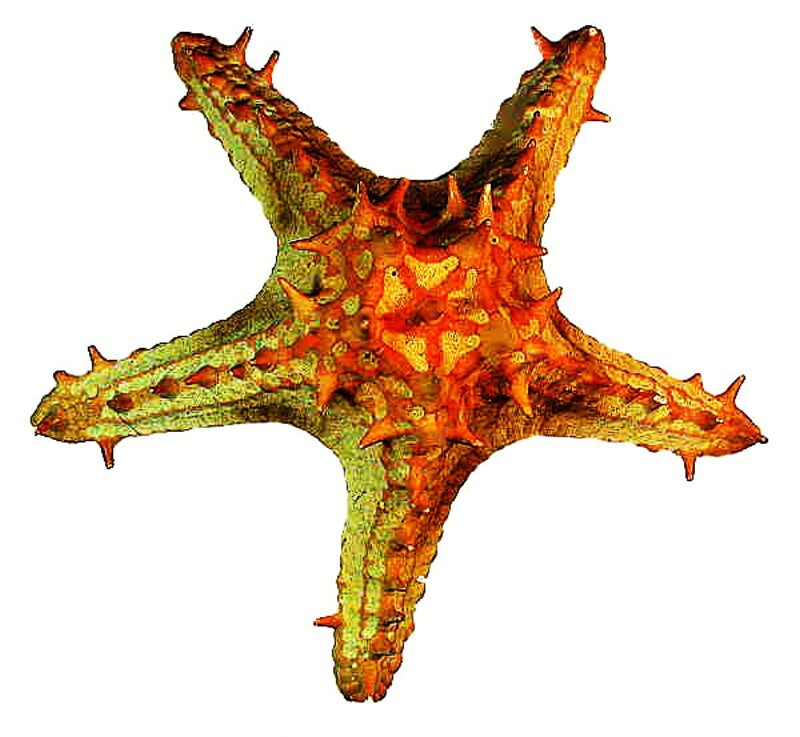

While we’re in the realm of echinoderms, let’s look at some starfish. One that I find impressive is the spiny starfish from the tropics, Protoreaster nodosus. When alive, the colors are much more intense with the creamy disk sporting the vividly red knobs. Nevertheless, even dried, they are very attractive.

Most of the dried starfish sold to consumers tend to be a rather bland tan color; however, there are striking exceptions but, you must exercise a bit of caution; if you find green ones with bright yellow smiley-faces lined up along the arms, the chances are that they’ve been altered a bit. There are purveyors of craft materials that indulge in the rather extreme kitschy sorts of alterations to sell items to the gullible and/or tasteless. This applies not only to starfish, but also to various sorts of shells which are sometimes dyed or cut or both. Depending on how the cuts are made, the results can be instructive regarding the morphology of the mollusk or they can simply be an attempt to enhance its appearance as an “ornamental” object. Below is an example of the latter.

However, as we noted previously, a sliced Nautilus can be instructive regarding the way in which the shell is formed and this is true also for other specimens when cut in proper sections.

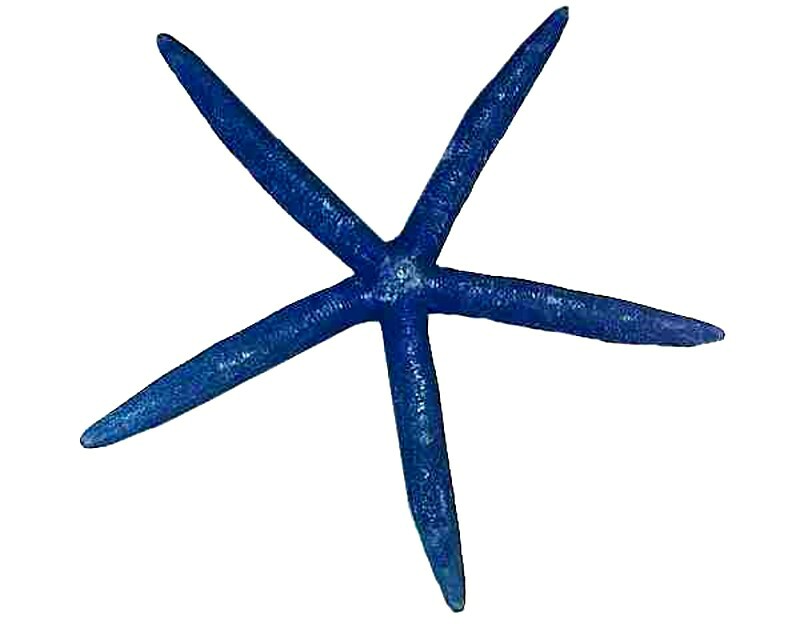

Dyed starfish, however, in my view, are an abomination. Below is a blue Linckia.

Surprise! This is NOT dyed; it’s the real thing. However, you should in general be suspicious of any solid pastel starfish that you find in a craft shop. Linckia is an amazing genus and has extraordinary regenerative powers. Most starfish can produce some spectacular regeneration but they virtually always require a portion of the central disk and an arm to perform their magic. There are however, reports of Linckia regenerating from a single arm. Echinoderms in general possess impressive potentialities for regeneration and much more medical research should be devoted to investigating and trying to understand these phenomena. Think of how wonderful it would be if, instead of having highly invasive surgery, such as a hip transplant, we could induce the body to undertake repair, regeneration, and restoration of the function without having to introduce alien metallic, porcelain, or acrylic substances into our bodies.

Starfish are not, however, always loved. Oyster fishermen hate them; reef enthusiasts and environmentalists hate certain species especially, Acanthaster planci, the Crown-of-Thorns starfish, which preys upon coral polyps and is responsible for having already destroyed enormous areas of tropical reefs in the Pacific. Here is a look at a dried specimen.

You can’t just chop up starfish and toss them back into the sea, as the oyster fishermen discovered to their dismay in the 19th Century–for some of those pieces will regenerate and form a new starfish to prey on the oysters. The same is, of course, true for the Crown-of Thorns. One of its major predators a large mollusk called Triton’s trumpet (Charonia tritonis) has been radically over-collected by shell enthusiasts thus helping to set the stage for a population explosion of this starfish. To make things worse, when divers go down to try to clear a section of the reef, they must take special precautions because the spines of this starfish contain a powerful toxin.

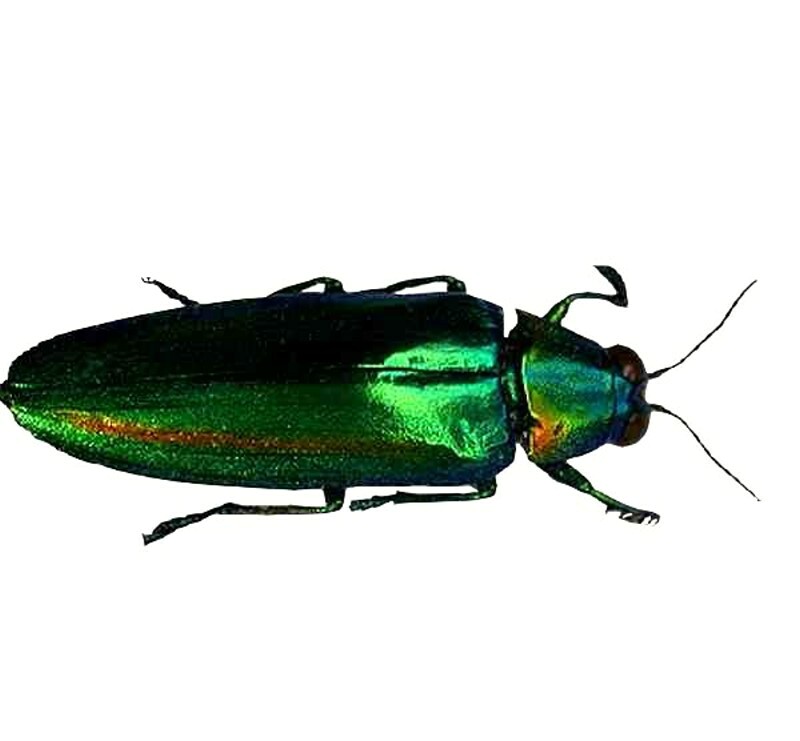

My cabinet also contains a few specimens of beetles and I’ll show you 2 of them here. First, a specimen from the brilliantly colored genus Chrysochoa.

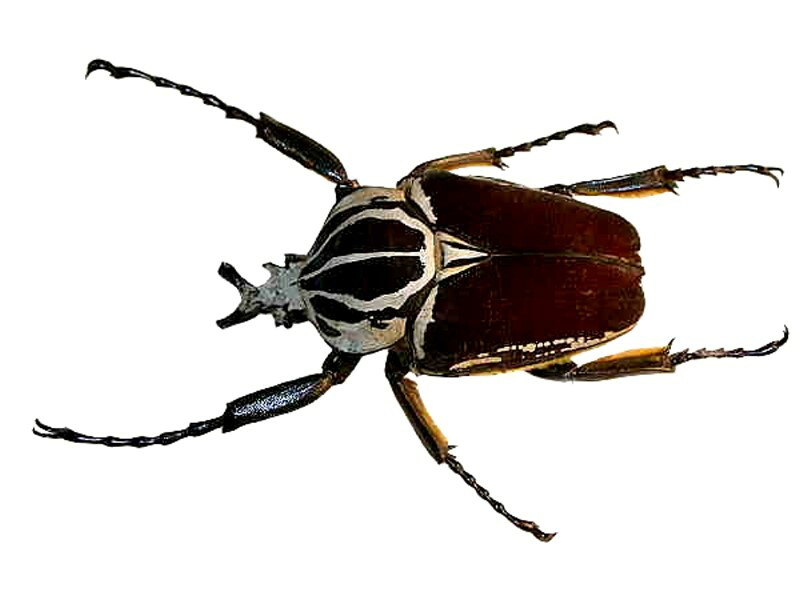

And next, a splendid specimen of stag beetle (Lucanidae) of the genus Cyclommatus some specimens of which look like they are miniature metal sculptures and then this one which looks like it was delicately carved from a piece of fine wood.

There was a period when I collected 50 or so specimens of tropical beetles, along with a large centipede, and 3 or 4 leaf insects and a couple of stick insects. I put these in Riker mounts and am now in the process of mounting them on the walls of my computer room–no more room in the cabinet.

The beetles range from the small Phaenus which looks like it was carved out of jade to a 6 inch giant–a Goliath beetle.

My cabinet also contains several specimens of selenite, a mineral often used as a compensator with polarized light in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. It is a form of gypsum and is still used today in certain types of compensators. If you find a German one marked “Gips”–that’s a gypsum one.

Selenite is one of those enigmatic substances that can take on a wide variety of forms, some of which are readily obtainable and even have garnered popular names. For example here is a “Ram’s Horn Selenite”.

And a “Fish Tail” Selenitie.

And the very popular “Selenite Rose”.

I also have a specimen which I especially prize, though it doesn’t have any economic value. Its form is especially pleasing to me and I think of it as a small piece of natural sculpture

I realize I haven’t documented everything in my cabinet, but I don’t want to get tedious, so I will conclude with yet another example of a glass sponge which is also rather like a small sculpture. It tends to occur frequently on the shells of the mollusk Xenphora–a fascinating creature which I quite like because, like me, it is a collector and one can find not only these elegant sponges but, other mollusk shells, tube worm shell, bryozoa, etc.

On another occasion, I shall share some additional items from my cabinet.

It is, I think, very important for the amateur naturalist to have such a cabinet, even if it is a small and modest one, for it is a place to house a few very special treasures which, while they may have little intrinsic worth, may be worth a fortune in terms of memories and as objects of contemplation.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the October 2015 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .