An Early Victorian Microscope.

By Joseph Casartelli, Manchester.

By Ian Walker. UK.

Introduction.

For some time I have owned a Victorian microscope manufactured by Joseph Casartelli, this name will be to many an 'unknown' regards historical importance in microscope manufacture. Over the years I have owned, refurbished and sold a good number of microscopes from various makers some of early manufacture and others of mid to late 20th century but I would be hard pushed to say they have given me as much pleasure as this scope. Joseph Casartelli was described, as many were of the time, as a scientific instrument maker and his main output was of measuring instruments for industry, the microscope side was, from what I can discern from the records in books, mainly limited to relatively simple microscopes for checking the quality of cloth known as linen provers.

Along with Ross and sixteen other microscope manufacturers he entered the International Exhibition of 1862 held in London which was a show piece of the time for manufacturers but with a definite aim to publicise the skills of British engineering around the globe at the time. It will come as no surprise to see Ross, Powell & Lealand and Smith Beck & Beck being pre-eminent in the microscope section whilst Joseph Casartelli received no special mention along with a number of the other smaller manufacturers some of which are better known such as W. J. Salmon. I do wonder if this had an affect on him since as far as I know there are very few of his scopes such as this one in existence, he may have decided to concentrate on his main output and give up making large scopes. It is quite possible that this type of stand or similar was submitted to the exhibition since more than likely it would have been his No.1 stand and would have been like the other makers, to illustrate his manufacturing skills to best effect.

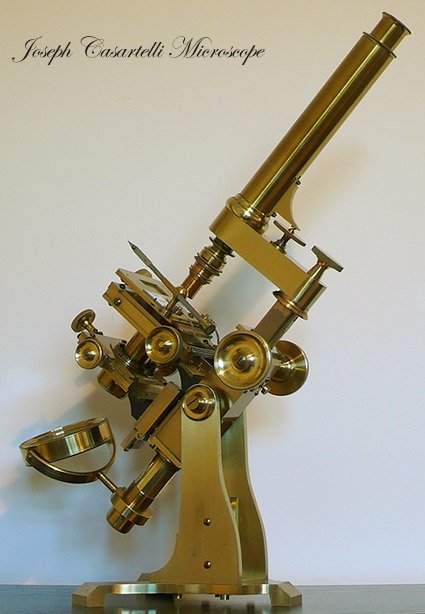

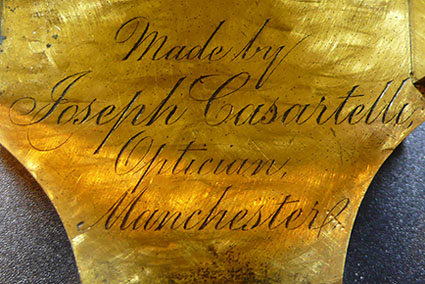

Fig 1.

The complete microscope with 'claw foot' bar-limb design introduced by Andrew Ross.

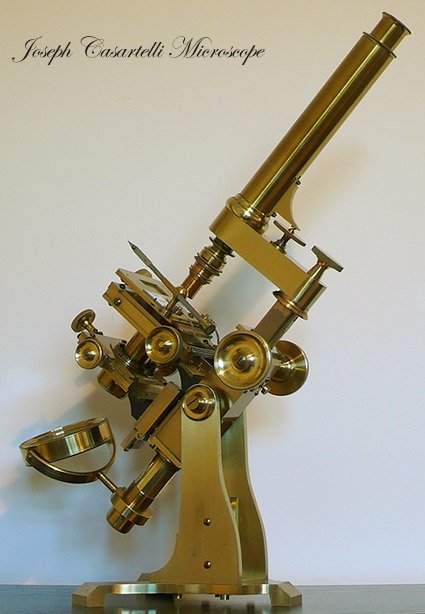

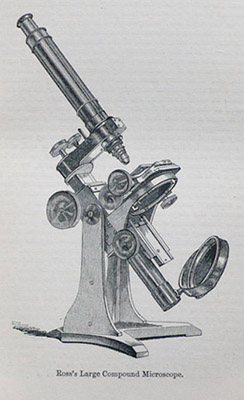

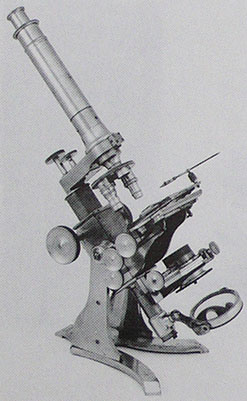

Fig 2a.

On the left in Fig 2a. a Ross large compound microscope illustrated in Carpenter 2nd Edition 1858. Andrew Ross died in 1859 passing on part of his business to his son Thomas, no sub-stage condenser is shown fitted. On the right is a later Salmon microscope which also has similarities with the Casartelli including rotating top plate of the stage, chain drive in this case for the 'Y' motion on the stage and a four position flat plate nosepiece rather than Casartelli's three as shown in Fig 2b. below and the sub-stage has a similar layout too.

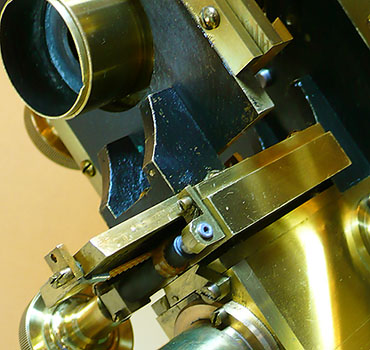

Fig 2b.

Casartelli three position click-stop nosepiece.

Fig 3.

Script by Joseph Casartelli, Manchester inscribed on the 'claw foot', he bought the Manchester premises in 1851, the same year as the Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace, London where early microscopes from Andrew Ross and Smith & Beck took the major awards for design quality and finish of manufacture. Barometers and other measuring instruments by the Casartelli family that I have seen have all been made to a good standard regarding engineering and finish.

Some Notes.

You will not find mention of Casartelli in Bracegirdle's book on Microscope Manufacturers, different editions of Carpenter, Hogg or other microscope books suggesting either his output was very small in this area or he did not submit any models for review. There are some interesting features on the scope like chain drive for the 'X' control on the complex rotating stage and chain drive to the condenser focus of the sub-stage, a mistake I believe due to the substantial weight involved. indeed this is no longer used because the chain has worn over the many years, slipped and then snapped and I have manufactured my own replacement belt which has worked well for the time I have had it. In the future I will try and get a replacement chain made by a small specialist company in the UK who can make-to-order. It was not unusual at this time to find chain drives being used by some manufacturers in the course focus and stage controls of the 1850-1860's but the idea was dropped in the next decade in favour of the universally adopted rack and pinion.

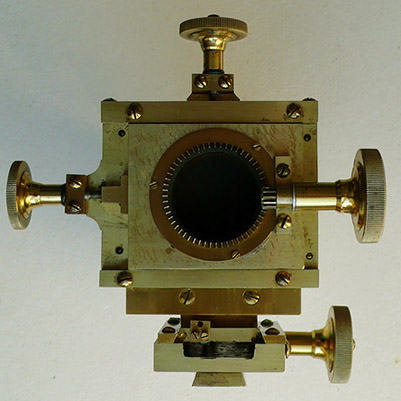

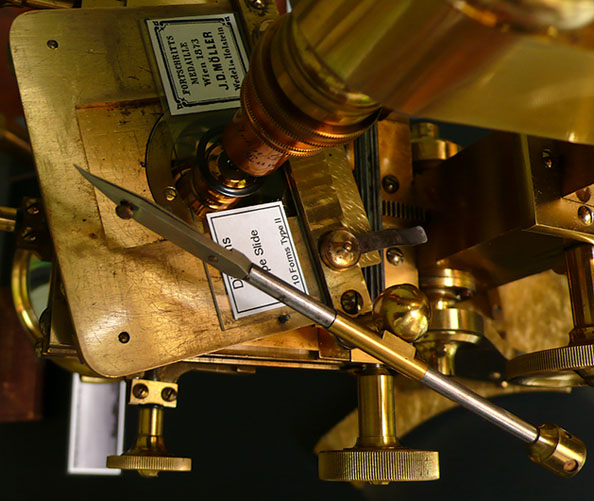

Fig 4.

Home made replacement for the chain that operates the condenser focus, this was built from crimped and glued solder tags bent into position and a strong none stretching toothed belt from a defunct VHS video recorder where many useful parts can be obtained. To provide more grip the steel shaft has been enclosed in a heat shrink rubber sleeve, the basic operation is exactly the same as the original chain drive. In the future if a replacement is available it can be put back without any sign of the work I have done, this is the case with other slight modifications carried out all of which can easily be removed to restore the microscope to its original build. The sub-stage is mounted on a dovetail and can be removed from the stand easily by turning the single screw operated lever shown centre bottom in Fig 4. above.

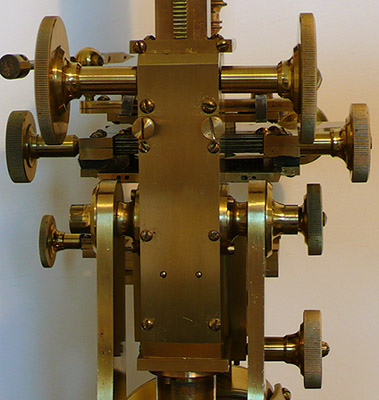

Fig 5.

Heavy sub-stage with condenser removed, wear [screw] adjusters are just visible for the 'X' motion at the top left and right corners of the square plate which pull in the dovetail slides together with the standard screws for holding the brass slides in place provides smooth control with adjustable tension. These are not that easy to set up and take time since a total of six screws need careful adjustment to obtain the same tension across the full travel of the slide together with different lubricants for 'X' and 'Y' directions to obtain the same feel.

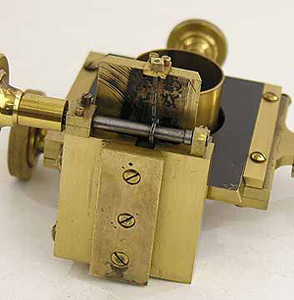

Fig 6.

Push-in condenser holder for the sub-stage which in this picture is housing an adapted Watson 1/6" objective rather than the original screw-in condenser. A fixed stop beneath the condenser also allows small filters to be placed on top where I normally have a green one in situ. No adjustable condenser diaphragm is fitted, the fixed stops on a turret can only be fitted to the sub-stage separately but this was not un-common at the time. For the low power objectives I haven't noticed a discernible improvement when fitting home made stops made from circular card but I have a choice of two for the 1/4" and immersion objectives. For the lowest power 2" objective the condenser can be removed and the concave side of the mirror used to good effect.

Fig 7.

Original chain drive to adjust condenser focus fell apart.

Also featured are a Ross style single objective carrier, 3 position 'click-stop' detachable nosepiece and adapter for taking R.M.S. objectives, fully centrable rotating substage with achromatic condenser and adjustment for wear on most sliding surfaces through the scope although not as well implemented as some of the best makers. The scope is housed in a well fitted mahogany box with red felt lining to two of the four accessory drawers.

Fig 8.

Ross style nosepiece with Casartelli R.M.S. adapter ring allows the use of objectives such as this John Browning 1/4" with correction collar presently racked up, also shown are the stage clips swung out of position, the 'Y' stage controls can be seen and part of the large course focus control to the bottom right. A single steel pin on the stage allows very precise replacement of the slide which sits on a well machined ledge. The stage is complex allowing partial rotation as well as an extra sliding surface to make large excursions of the top plate which also has holes to accept stage forceps, not shown, this together with the standard 'X' and 'Y' controls.

Fig 9.

Detail of the complex sliding stage assembly with the top plate partially rotated, together with stage forceps and showing the left 'Y' stage and 'X' sub-stage controls. The general quality of engineering is to a good standard. Just seen beneath the slide is an accurately centred Watson 1/6" NA 0.87 objective acting as a condenser, the precise and fine control of the substage allows easy centring at all powers or off axis oblique if desired.

A little history.

Joseph Casartelli was born in 1823 in Tavarnerio in northern Italy and emigrated to Liverpool with his family when Joseph was just 11 years old. After Joseph was seen to excel in the instrument making trade of his family he was allowed to buy out Joshua Ronchetti's instrument making business in Manchester and in 1851 he had taken over, the same year as the Great Exhibition held at Crystal palace, London. The Ronchetti's were known to Casartelli's back home in Italy and Joseph married Joshua's sister, Harriet. Joseph expanded the business and became an important figure in Manchester manufacturing optical instruments, surveying equipment and engineering instruments.

As well as manufacturing Joseph became involved in civic projects including sending rainfall data to the press and recognition of his work by his election as a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1858. Joseph was innovative and made patented improvements to instruments of the time including steam pressure gauges and pyrometers. Joseph had a son Joseph Henry who at the age of 20 joined his father in Manchester which in 1882 was based at 43 Market St. although through the long life of the firm the premises changed a number of times. It is possible this early scope was built at the smaller workshop of Robert St, Cheetham. After a long career Joseph died at the age of 77 in March 1900 but his son continued in running the business and thereafter his son in turn continued with later years manufacturing which diversified into instrumentation for the mining industries. The firm finally ceased trading in 1989 after 144 years of continuous manufacture, along the way the Liverpool branch run by Anthony Casartelli & Sons was taken over by the Manchester firm in 1929 which was started in 1845 but in 1933 finally succumb to the Great Depression and was closed down due to financial difficulties ending 88 years of instrument making.

I contacted the Museum of Science & Industry in Manchester some time ago to see if they had any information about Casartelli regarding microscopes but unfortunately the Senior Archivist could offer little information, the above notes are from an article written for the Powerhouse Museum Collection based in Sydney, Australia.

Some thoughts on the microscope.

I have never seen another Joseph Casartelli microscope so cannot judge whether this was typical of his design but the similarities between this stand and a large Ross of the same vintage is interesting. Andrew Ross set the 'blue print' in design of large stands of the mid 1840's which continued in various form all the way through to the 1870's with the 'claw foot' bar-limb copied by several manufacturers in Britain and it is no surprise to see many of the elements of the Ross here, a look at early Ross, Baker and J. Swift microscopes of the period in G.L'E Turner's 'Great Age of the Microscope' show similarity down to the complex centrable and rotating sub-stage and substantial height and weight of the instruments. There is no doubt that Ross finished and manufactured to a very high standard and was the one of the leading manufacturers of the time but Casartelli should not be under estimated, it is a well finished microscope in a light golden lacquer of good quality and as mentioned before most parts are adjustable for wear, making it as usable today as it was over 140 years ago.

I cannot date the scope exactly, it cannot be earlier than 1851 and my best guess is either:

[1]. Before 1858 when the R.M.S. [Society] thread was officially introduced to gain uniformity and inter-changeability of objectives between makers which for the most part from the sources I have seen was taken up very quickly by English makers or:

[2]. A little later say around 1862 since the objectives supplied by S. Highley marked 70 Dean St. London is from his 1860's premises rather than the earlier location of 32 Fleet St. in the 1850's, also included are two from Casartelli marked on the containers and a James Swift all have been fitted for the drawer that contains them, the makers containers are not inter-changeable within the drawer due to the different diameters suggesting they may have been fitted up at the time of manufacture as a set which would have been a 2", 1", 1/2", 1/4" which is logical although by 1862 the society thread had been in use for four years and it is possible the later Highley and Swift have been adapted to work with the Casartelli [Ross] thread to make the microscope more versatile although close inspection of the objectives all parts I would say have been made at the same time.

The objectives themselves are a little confusing since some of the containers originally marked have later scribed inscriptions for 'magnification' [in inches] but the J. Swift is unaltered and dated 1862 1/4" with cover slip adjustment [this is early for James Swift since he only set up business after leaving Ross in 1857 5 years before] and as mentioned above been adapted for the Ross internal thread. The two lowest powers, a 1" and 2" are by Casartelli but quite possibly made by another optician and supplied to him as often was the case and are quite plain and unmarked on the objectives however they are both competent optically.

Fig 10.

Objectives by S. Highley [1/2"] and James Swift 1862 [1/4"] with correction collar.

Fig 11.

Further objectives used with this stand include from left to right an early Reichert 1/18th NA 1.18 water immersion with internal Ross type thread, Spencer ca. 1890 3mm NA 1.10 water immersion and two Zeiss Jena objectives. The first a 3mm apochromat NA 1.40 with script on the barrel putting the likely manufacturing date between 1897 and 1904 since the third series of Zeiss apochromats were introduced in 1897 [many of the first used unstable glass and became useless in hot climates, the 2nd series didn't include this objective] and the logo changed from script to the 'achromatic doublet' logo so well known over most of the 20th century in 1904. A 3rd quarter 20th century 'A' is also used, the magnifications will not be as stated for use with the Casartelli.

Although spherical aberration due to the objectives being designed for the continental 160mm tube length will be apparent I'm happy with the images obtained and prefer using them on this stand rather than more modern stands and I have done several comparisons of the effects of spherical aberration when used on the Casartelli compared to a Zeiss stand fitted with Abbe condenser and to my eyes, acceptable. The Zeiss 'A' being of only around 8x [160mm] no difference in image quality can be seen when used on the Casartelli other than the stated magnification. The Zeiss 3mm apochromat like so many of their output is delaminated on several planes which affects the contrast too whilst my favourite is the Spencer, an easy to use objective with good working distance to make observation fuss free.

Casartelli decided to use a stage where the 'X' and 'Y' controls are at right angles to each other rather than the common 'one above the other' on the right hand side [See Ross and Salmon in Fig 2a.] and initially this seems to be a nuisance but I find it useful for searching a slide quickly to find the subject with medium powers like the 1/4" objectives since I can use both hands at once and go in any direction, diagonally included. The reason for this layout is the use of the chain drive for the 'X' motion which due to the small link size provides a 'fluid' movement free from the rack and pinion 'cogging' where meshing of gears is not always perfect and deterioration of feel due to slack because of wear can occur over years of use. His method was a sound one since he probably used common fusee chains of the time and easily replaced by post by Casartelli to the customer, a made to measure rack or pinion damaged would need the scope sent back to the firm.

Fig 12.

The 'X' motion of the stage is controlled by friction fit chain drive on a steel spindle, simple adjustment is available for tensioning or removing the chain, you would think the grip might be poor but given the right tension it is surprisingly good and provides smooth operation.

The 'tube length' is an intermediate length with no draw tube, an error on Casartelli's part since the predominant makers at the time included this facility to compensate for cover glass thickness if objectives were not fitted with correction collars. The fixed 'tube length' measures 8" rather than adjustable above and below 10" adopted by English makers using the standard measurement points but this was probably due to the attachments like the special centring single objective carrier or 3 position nosepiece which added extra length. In daily use this intermediate tube length doesn't cause any problems without the above accessories and I have used low power objectives of later period by Zeiss and English objectives designed for 10" [250mm] tube length as well as water immersion and oil immersion for both English and Continental tube length as shown in Fig 11.

Fig 12.

The course focus rack is straight [seen at the top of Fig 12.] unlike the diagonal or spiral introduced later by other leading makers and because of this does have inevitable 'slight play' even with wear compensation screws but with careful use of the very large focus controls and appropriate lubrication to the sliding surfaces I can easily bring into focus the 1/18th Reichert water immersion with this control only. A clever design of a heavy solid rod running in a close fitting tube [part of the mirror tube] attached below the course focus mechanism provides a damped light action and precise focus with appropriate grease. Adjustment to course focus stiffness is by the uppermost screws on the long brass cover plate shown followed by rack and pinion adjustment on the larger screws below, removing the plate provides access to the rack work.

Maintenance and repair.

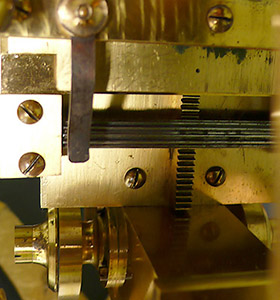

I have completely dismantled, cleaned and re-lubricated a good number of microscopes over the years and after a while get an intrinsic feeling for what lubricant is best for different mechanisms but over the time I have had this scope this has been an interesting problem to get right, due to the approximate 60 degree angle of operation on my table I have found different lubricants are needed for 'horizontal' and 'vertical' motions of the various moving parts so the chain 'X' drive for the stage has a lighter lubricant than the 'Y' motion, a heavier more viscous lubricant was required, this is reflected throughout the microscope with different lubricants on each surface being used for best feel due to all the various angles and gravitational effects. Initially and for some time after I bought the scope I tried various lubricants not always getting it right but after several months of use with some experimentation I have found a good setup with a microscope that is a pleasure to use after nearly one and a half centuries with smooth and precise operation on all controls. Tightening the two screws at each end of the pinion for the 'Y' control [the left pair on the small plate can be seen in Fig 13. below] requires just the right amount of torque, stiff and the adjustment can affect the focus slightly as the 'Y' motion is carried out, too loose and it drifts down under gravity, using the right grade of grease is also needed to obtain the best effect without drift.

Fig 13.

Rack and pinion 'Y' control, with one of the 'swung-out' stage clips.

The fine focus shown in Fig 14. below is a direct acting screw on the objective holder with spring return within the main tube assembly, although a hardened steel insert was used on the underside of the focus arm the conical screw end piece does not appear to have a hardened tip so wear is inevitable and causes slight motion of the object under observation as it is turned with medium to high power objectives which is a shame, for lower powers the fine focus is not needed. The action of the screw itself feels very good using a trace of Kilopoise 0868 lubricant on the very fine screw thread. Ross used a double counter-sprung fine focus screw and lever mechanism on his microscopes at this time providing isolation between the screw and focus action and adding a mechanical advantage providing less wear on the screw.

Fig 14.

Direct acting screw fine focus notice the hardened steel insert on the underside of the brass focus arm, Early Ross used a lever mechanism of which a schematic can be found in an interesting article in the Quekett Journal July-December 1972, 'A critical comparison between the No.1 microscopes from Ross and Powell & Lealand' by P.K. Sartory.

Slight wear on the steel 'ball' running between the fixing plates within the sub-stage centring controls was eliminated by specially filed out and sanded down rubber 'O' rings which act as cushioners and slip rings and then lubricated to provide an excellent feel from the controls, although wear adjustment is incorporated I prefer to have the screws a little looser and use my slip rings, they are discrete and allow a very free movement to centre my 'achromatic condenser' provided by a Watson 1/6" objective replacing the supplied one for higher power objectives which has insufficient NA to obtain good results from the immersion objectives. To use an objective as a condenser is not ideal situation as the optics were never corrected for use under a slide and the working distance insufficient but it works well considering and obtaining early high NA achromatic condensers that could fit a stand like this is almost impossible to source.

Fig 15.

Adjusted rubber 'O' ring fitted to sub-stage control, the two screws allow adjustment of the tension on the internal 'ball' on the screw between the plates, as with many of the instruments of the time you must remember the orientation and position of each hand made part [in this case the two brass plates] since they fit well in only one position.

Although the Watson objective acting as a 'condenser' cannot be focused for some slides of greater thickness it works well and is of higher NA than the supplied condenser which is about 0.5 although well corrected. This fairly low numerical aperture is not surprising since the supplied objectives only went upto 1/4" [40x on a 10" tube] and would be well matched to this figure. The John Browning 1/4" is marked 86 degrees [NA 0.68] although rather optimistic as it can only just resolve Pleurosigma angulatum with some oblique applied. Filters can be placed below the condenser if required on the fixed stop and I have made various colours. With the addition of easily off-setting the condenser using the sub-stage controls and varying the large 3" mirror, different degrees of oblique can be achieved with ease. For the lowest power objectives no condenser is needed just the concave mirror. The condenser holder is a tight push fit in the sub-stage with larger excursions in height by 'push-pull' as well as using the finer control by the focus control.

Accessories.

Fig 16.

Shown above are two good quality compressoriums of differing style, the right providing fine control of pressure, an adapter to allow centring of an objective on the nosepiece, variable diaphragms for the sub-stage and one of the four drawers enclosing the objectives supplied in cans and a 3 position 'click-stop' nosepiece. Note the sub-stage diaphragms cannot be used at the same time as the condenser which is a shame. All the accessories fit neatly into cut-outs specially made for the purpose in the drawers. Also included are stage forceps and polar attachments some of which are shown in the left drawer of Fig 17. below.

Fig 17.

The two felt lined drawers house the four eyepieces, Lieberkuhn for the Casartelli 1" objective, simple Camera Lucida and the accessories shown in Fig 16. Also included are the original polarization attachments but only the push-in sub-stage polarizer is shown here, the analyzer is in another drawer which included various small boxes of cover slips of the time.

Fig 18.

The mahogany box is substantial, beautifully crafted and finished, here shown with the microscope out and enclosing some general microscope accessories, a sliding tray at the base allowed easy access to the fitted microscope whilst a large 3 1/2" diameter auxiliary condenser on a brass stand could be dismantled and fitted within the box, not shown but supplied with the microscope. On the top of the box is a heavy duty brass handle within its recessed lacquered brass plate but unfortunately the lock and key are missing.. quite common.

Regular use.

The microscope is imposing standing over 17" high to the eyepiece at a typical operating angle but this is one of the reasons I like it because all the parts are nice and 'open' unlike many of the later continental designs of the early to mid 20th century. One draw back of a quite shallow operating angle comes about using immersion objectives since the oil has a tendency to thin out where it is applied specially with modern immersion oil but with a bit of practice and quick descent of the objective I have got round this.

The 2" and 1" Casartelli objectives provide bright, sharp images on plant sections and so forth and can also be used for simple polarization experiments with appropriate accessories whilst the John Browning 1/4" dry bought separately and Spencer water immersion objectives provide pleasing images and ease of use with Victorian and modern slides of diatoms. The Swift 1/4" although been checked throughout is somewhat disappointing with rather 'milky' low contrast images regardless of cover slip adjustment.

An afternoon experimenting with a Sony P200 digicam at the eyepiece didn't work successfully mainly due to difficulties focusing, camera shake and the very limited flatness of field typical of the objectives of this vintage when successful shots were taken, however to me this does not detract from the original purpose of the scope which is for visual observation.

The imposing auxiliary condenser also known as a 'bulls eye' is not a doublet and therefore poorly corrected but can be useful under certain circumstances but it can easily be swung in and out of the light path for experimentation. The precise method of off-setting the condenser and large mirror provides oblique illumination on low contrast prepared slides and both are a pleasure to use. I like this microscope, like an old sports car it needs lots of loving care with a bit of lube here and a tiny adjustment there on a fairly regular basis but given its age it provides an enjoyable accompaniment to reading books of the same age.

The quality of light used bears a significant part in obtaining the finest images, of the time the edge of a flame was often used to illuminate a single area just wide enough to illuminate the subject specially diatoms this reduced glare from the objectives. I use a low power daylight corrected fluorescent lamp which can work well but in the future I want to do experiments with clear filament bulbs, the pearl surface of opaque lamps I think reduce fine detail like straie of diatoms.

Ending thoughts.

It is a shame that a good number of early leading make microscopes like Powell & Lealand, Andrew Ross, R & J Beck etc are bought ..sold.. bought again [the cycle goes on] through auction houses whether it be Christie's of London, Sotherby's or auction houses around the world and perhaps rarely used for their original purpose being purchased by collectors wanting 'show piece' items for their homes.

To leave these microscopes for very long periods without use, especially as it is quite possible they will have much of the old lubricants in situ, is to have a microscope which will eventually seize and malfunction to a point where in the long term future it will be difficult to restore them to a good working state, this together with a number of the objectives that will have growth of fungus, finger marks and detritus within the body and on the front element of the objectives, which is certainly the case with most of those I have bought will, if left for long periods, destroy its optical qualities. Some are beyond repair, others like certain of the objectives of Powell & Lealand were not designed to come apart but others if carefully and thoughtfully refurbished both microscope and objectives can be brought to life in most cases and perhaps once again the observer can see many slides and objects as Victorian microscopists' would have seen them well over a century ago.

It is quite possible if you spoke to an antique dealer or professional restorer, 'leave alone' would be the answer but I'm amazed just what a difference some sensible renovation can make, I have seen objectives and eyepieces transformed from poor to competent just by careful cleaning and the beauty of many of the simpler achromat designs like the Spencer water immersion and low power objectives is they dismantle into manageable sections with the glass elements securely placed by screwed retaining rings. Some, like the apochromats by all manufacturers are complex with several sections of which exact spacing's are critical and best left alone in most cases but others like the Reichert front element of the 1/18" was covered in hard opaque deposits probably from old immersion oil from years past impairing the image but careful cleaning brought it to a very acceptable condition with fine gloss on the glass and the results, a substantial improvement of contrast and resolution. Each case must be considered.. whether to clean or leave it comes down to common sense most of the time and whether you have the right materials for the job, areas I leave are original lacquers which I only gently clean without rubbing with a dampened fine cloth and mechanical parts of the scope where it is impossible to refabricate the part without specialist knowledge and indeed if it is of great historical importance whether to leave it to history and don't touch it at all.

Just how smooth were the controls on a Powell & Lealand No.1 and how good were their apochromats, is it an easy microscope to use, was the fit and finish on a Ross as good as they say, how does it compare to a top stand by R & J Beck and what about the achromatic condensers, how do they compare to modern stands and optics.. for the most part we will never know except for notes in books written at the time from Carpenter, Hogg, Spitta and van Heurck but rarely in an up to date and modern context. These microscopes should be used today as they were when they were built to be written about, experimented with through day to day observation and their qualities shared good or bad. Few can ever obtain a Powell & Lealand or early Andrew Ross but hundreds of interested folk can share the beauty, workmanship and optical expertise of these early stands if the microscopical societies, museums and collectors who own them are willing to share their knowledge—not just a glossy photo and entry in a book or website but to be written about in detail and comparisons made whether by book or microscopy websites—anything else is a loss of optical and mechanical engineering of a different age gathering perhaps not dust but certainly going to waste.

Comments to the

author,

Ian

Walker

, are

welcomed.

Published in the October 2007 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd,

Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All

rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk

with full mirror at

www.microscopy-uk.net

.