|

A Close-up View of the Wild Flower

(Dipsacus fullonum) by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

|

A Close-up View of the Wild Flower

(Dipsacus fullonum) by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

Many wild flowers are valued for their colour or scent, but it is the striking architectural character of teasel that initially captured my interest. The plant, which can be up to two metres high, usually dominates the landscape where it is found. Teasel grows from seed in the first year to produce a ring of leaves close to the ground. If conditions are good, the flowering stalks seen in the image above are observed in the second year. After flowering, the plant dies, and the resulting brown stalks and heads may stand for several years before succumbing to gravity.

In early summer, the egg-shaped heads (inflorescences) have a sculptural quality, with the spiny stem supporting a ring of stiff, prickly bracts. The head, with its sharp bristles, is also very prickly. It definitely helps to wear gloves when cutting or handling teasel!

Teasel is unique in the plant world in the way in which it blooms. Flowers form first in a ring around the middle of the head. This ring grows in width over a few days, but since the flowers are relatively short lived, the center of the booming section may die, leaving two rings, one growing towards the top and one towards the bottom of the inflorescence.

A closer view shows the flowers as they burst forth from the pink domes between the bristles of the head.

In the view below, the purple pollen covered anthers are clearly visible.

When viewed head on, the individual flowers can be seen. They are tubular with their open ends having four lobes.

In the image below, the flowering band has grown until it covers almost one third of the head. Notice the extraordinary ring of green bracts that branch out from the stem at the base of the head and curve up to surround it.

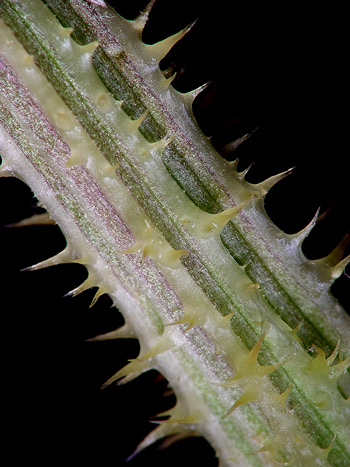

Clear evidence of the hand damaging characteristics of the stem is evident in the image below. The spines grow on ridges along the stem, and between these ridges are coloured bands ranging from red to dark green.

A slice through the head using a sharp scalpel, reveals more of this plant's unique structure. The head is heavier than might be expected, because it is filled with water containing tissue.

With some difficulty, I removed a single flower from a blooming inflorescence using tweezers. The tubular corolla with its lobed end, and the four protruding stamens usually present, can be seen. Both anthers and filaments are coloured a shade of light purple. The total length of the flower is about 12 mm.

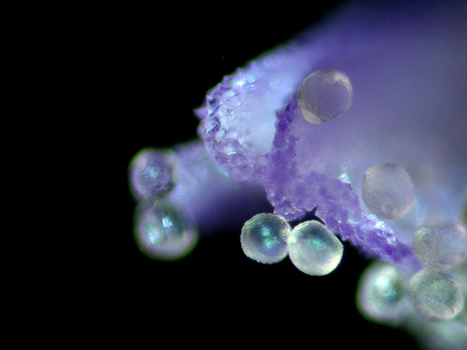

The image below shows some of the anthers in the flowering band. They are completely encrusted with white pollen grains.

A slightly different angle reveals the sturdy filaments holding the anthers, and the stiff bristles that surround them.

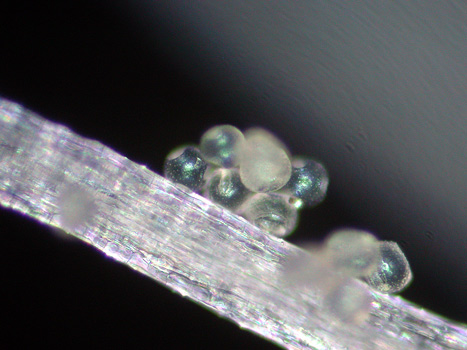

At a much higher magnification, several dimpled, spherical pollen grains can be observed clinging to a filament.

Pollen grains clinging to the rough surface of the anther are visible in the image below.

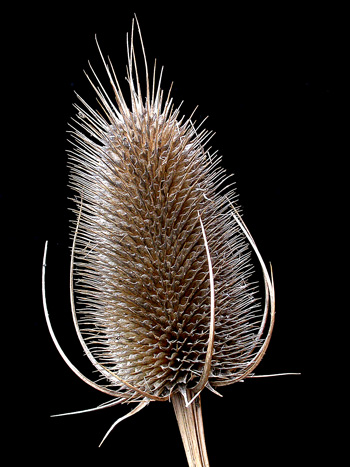

Eventually, the seeds are released from the head, and the plant dies. The image below shows a one year old head that has matured into a hard brown structure encrusted by stiff, sharp bristles. (The first image in the article shows other such heads.) For some years these dry heads were used in the wool industry to 'tease' the cloth and raise the nap.

Photographic Equipment

The low magnification photographs in the article were taken using a Nikon Coolpix 4500 with natural light and the Nikon Cool light SL-1. The higher magnification images were taken using a Sony CyberShot DSC-F 717 equipped with an accessory achromat which screws into the 58 mm filter threads of the camera lens. The two photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using polarized light), and the Coolpix 4500. For more information on the use of the equipment in producing the images please see my earlier article on the wild flower Chicory.

Conclusions

I spent this past summer taking thousands of photographs of wild flowers that grow in southern Ontario. As might be expected, several flowering plants proved to be my favourites. Of these, Teasel stands out because of its unique sculptural and architectural qualities. Both far away, and close up, this plant displays interesting and remarkable characteristics. Its details are as startling as its general form.

I freely confess to having ignored much of the botanical world around me for the past fifty-eight years! Digital photography has provided the impetus, and the means, to study the huge array of wild flowering plants in my vicinity. Photographing wild flowers is not difficult. Why not try it for yourself?

All comments to the author Brian Johnston are welcomed.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy

UK web

site at Microscopy-UK