NOTE: A plea for patience. I do take some time to set the stage, but I will get to some interesting aspects of microscopy (with some images) and I hope you will stick with me, because I think, in the end, you will find some things that are interesting and provocative.

Science, for all its extraordinary methodology, equipment, and pain-staking probing, examining, and testing, also depends upon trust. Unfortunately, in recent years, we have seen, on the part of the public, increasing mistrust in the results of scientific research and in scientists themselves. This is perhaps most evident now regarding the issue of climate change. Powerful economic and political forces want to radically downplay the significance of any change and attribute whatever change they are willing to admit to as natural, cyclic causes which go back millions of years. The most vociferous opponents deny in stentorian style any human contribution to the process and are particularly vehement in the denial of any role which coal, oil, or gas might play.

Thousands of scientists have been looking at climate change issues from a very wide range of perspectives, utilizing a vast array of techniques and over 90% agree that human beings are a primary contributor to global climate change through, especially, but not solely, the staggering overuse of fossil fuels.

Why then is there so much mistrust of the published scientific research? Well, if you were part of the system that harvests billions of dollars annually from fossil fuels, it is probable that you would be deeply distressed by such reports. Furthermore, you wouldn’t even have to be one of the multi-millionaires or billionaires to not want these reports to be true; you might be a coal miner or a worker on an oil rig and recognize that this science threatens your livelihood.

Vested interests are, of course, nothing new, but here we have issues which, if the scientists are correct, may affect the survival of the human race on planet Earth, possibly within 100 years or even less. What’s really scary though is that a significant number of scientists are saying that the radical upheavals of glacial melting, the breaking up of the polar ice caps and coastal flooding, the lssue of major food sources from the ocean, severe droughts that could lead to “water wars” might begin to happen in as few as 30 years. This means that you need to be concerned about possible impacts on your own children and grandchildren.

However, there are those who will spend staggering amounts of money to convince you that you can’t trust the science. Remember those old advertisements in which “doctors” and well-known actors (including one who was later to become President of the United States) recommended various brands of cigarettes?

The tobacco industry spent billions over decades combating the idea that there was any link between cigarettes and cancer. Well, we know how that turned out. I smoked cigarettes for about 30 years and I loved them; I was addicted–I liked the way they heightened my mental activity, helped me be more at ease in social interactions, and boosted my energy. Then, one November, after a severe bout of bronchitis, I quit and never touched another cigarette. I am a reasonably intelligent person, but cancer was never the issue for me. I knew it was a possibility, but I was simply too hedonistically oriented; more bluntly put, I enjoyed the hell out of smoking, screw the consequences.

It’s not that I doubted the science rather; in some respects, it was the crassest form of egotism in that I believed I would somehow be exempt. Thankfully, I never put that to the test. However, climate change isn’t like that; it isn’t that you can choose nor even that there is a possibility that some people will be exempt–this is, after all, global climate change and the deniers are involved in a massive deception.

Climate change is just one example; the mistrust in science has become epidemic–vaccinations are dangerous and cause autism, pollution of air and water are a necessary byproduct of progress–if you’re concerned, wear a mask and get a water filter (tell that to the citizens of Beijing and Flint, Michigan). Coal, we need coal, we just need to “clean” it up–a current political fiction driven by economics and, then there’s methane–well, yes, there is a bit of carbon dioxide associated with it and perhaps a smidgen of sulfur dioxide. And then there are those nasty scientists who think nuclear power is too risky–never mind Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima. One problem is what do you do if there is an accident? Another is what do you do with the tons of waste? the “byproducts”? The plutonium from Fukushima, PU-239, has a half-life of 24,100 years and remains radioactively dangerous for 10 to 20 time that long; in other words, at least a half a million years. (Perhaps we should just be grateful that it’s not Plutonium 244 with a half life of 80.8 billion years!!!) Oh, but apart from a few piddling mishaps, we get nice, reliable, clean energy–so these nit-picking scientists are just unnecessary trouble-makers.

Today, we face a catastrophically poor educational system compounded by a very large segment of the population that remains fundamentally uneducated. These difficulties are compounded by complex technologies that cater to ignorance and stupidity and constitute a pandemic of cyber transgenic disease through what is blithely called “social media” and should more accurately be understood as “asocial and anti-social media.”

What students (and indeed adults) desperately need is to develop their abilities to reason critically. Some years ago, some trials were carried out teaching grade schoolers basic techniques of critical thinking and logic. Its brief history indicated that it was successful in helping to develop these crucial skills. Why it was discontinued is unknown to me, but my naturally cynical nature leads me to suspect the primary reason may have been political and, secondarily, that insecure teachers and administrators didn’t like encouraging these “spawn of Satan” who had learned how to challenge their authority and hypocrisies. Scattered around the country are a few brave souls who still struggle to teach their students how to think and reason, I applaud them. However, it is not enough: not nearly enough. We need massive efforts, supported by extraordinary amounts of money (perhaps, the Pentagon could spare a little), and the support and encouragement of the brightest individuals in every dimension of our social, scientific, and cultural life. The trust in science and reason must be restored and made an essential part of our cultural identity, otherwise we are doomed to wander aimlessly in the realm of pixels and tweets.

So, finally, to some issues in microscopy. When we are presented with images and information, we need to be able to trust what is presented. This is not to say that we treat everything as gospel. I have encountered images of protozoa which were mislabeled and sometimes that is an historical problem where the identification has shifted over time. On other occasions, it may simply be an oversight or confusion. However, in general, we expect the supportive material to reinforce our acceptance and comfort with what we are told. In the area of microscopy, this is especially important because what is examined may involve familiar objects and substances which under microscopic magnification take on a “wholly other” appearance. This is even more the case when we are presented with images using sophisticated, innovative techniques and/or specialized modes of illumination. So, often some descriptive detail or information which provides a larger context is very helpful. Unfortunately, much of technical scientific writing in journals and narrowly focused books demands concise discussion and severe editing as a consequence of “page charges” for production costs. This can lead to some very bad writing and page after page of jargon-laden discourse that only the most patient specialist can relate to.

What I want to do here is present to you some examples of items which appear very strange but, in fact, are not really esoteric. Part of the issue is that we may just have never taken time or made the effort to take close-up looks at these things.

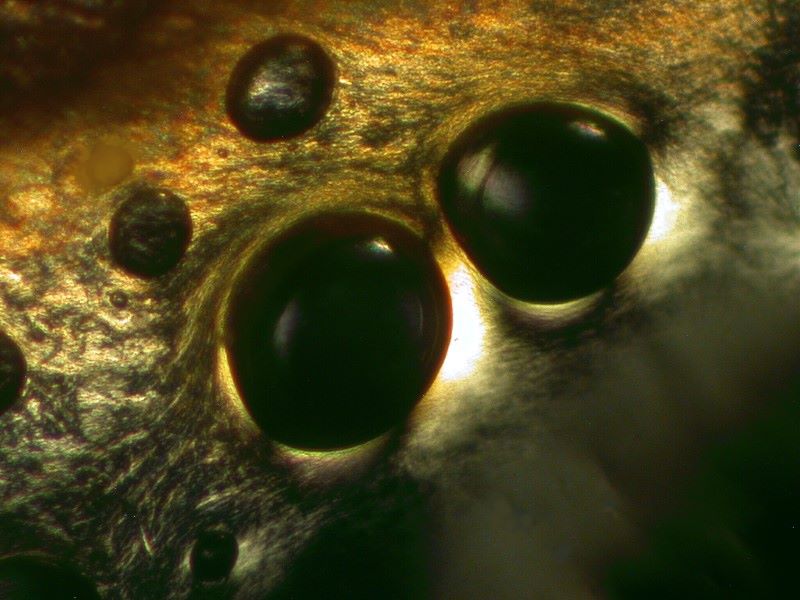

The first case is a perfect illustraion of the point. How recently have you looked closely at spider eyes? Those of you who are not arachnophobes have likely noticed that spiders have 8 eyes. This image capured only 4 of them, but they are nonetheless quite distinctive.

To many, it is disconcerting to imagine being observed by so many eyes at once and very keen eyes they are. We used to have some tiny jumping spiders who liked to hang out around the door bell to our side door. Every time, I attempted to capture one to observe, it would go leaping off out of reach and out of view. Frustrating!

Feathers have always been especially intriguing to me because of the extraordinary variety of shapes and colors. Peacock feathers under the microscope display extraordinary characteristics both in color and morphology; individual strands can appear as though they were wound with fine, micro-thin wire and, as is the case with many structures in nature, some of the colors are pigments, whereas others are the result of refraction. The image I’m going to show you is neither very colorful nor subdivided as a consequence of its being a fossil imprint. It is a fragment of an unidentified bird. However, it does share the typical characteristics of the central shaft and attached to that are the branches or barbs.

The natural world especially at the micro level is rich in geometric forms as one can easily recognize just by a cursory glance through some radiolaria, foram, or diatom samples. Let’s take a peek at a little cluster of diatoms.

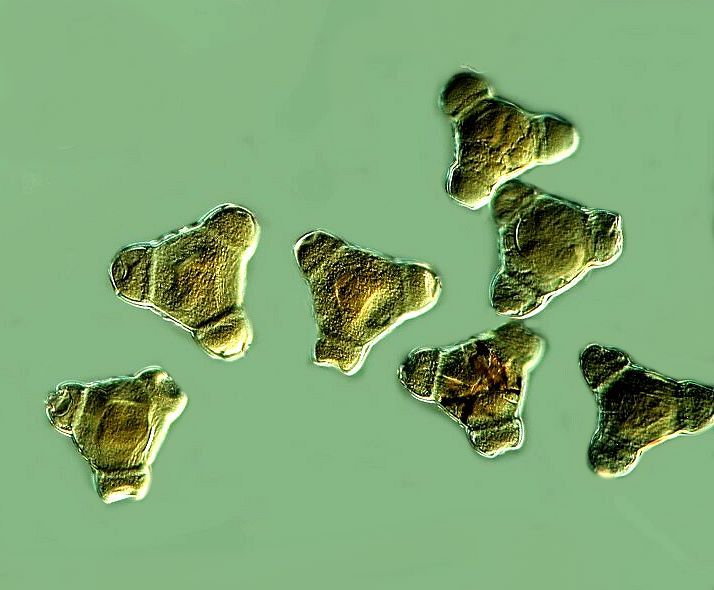

We need to keep in mind that nature doesn’t feel bound by the precepts of Euclid and so we will find all sorts of variants of “classical” geometric forms. In this case, we might think of these diatoms as truncated triangles or as hexagons with 3 alternating domes. In any case, they are quite attractive objects.

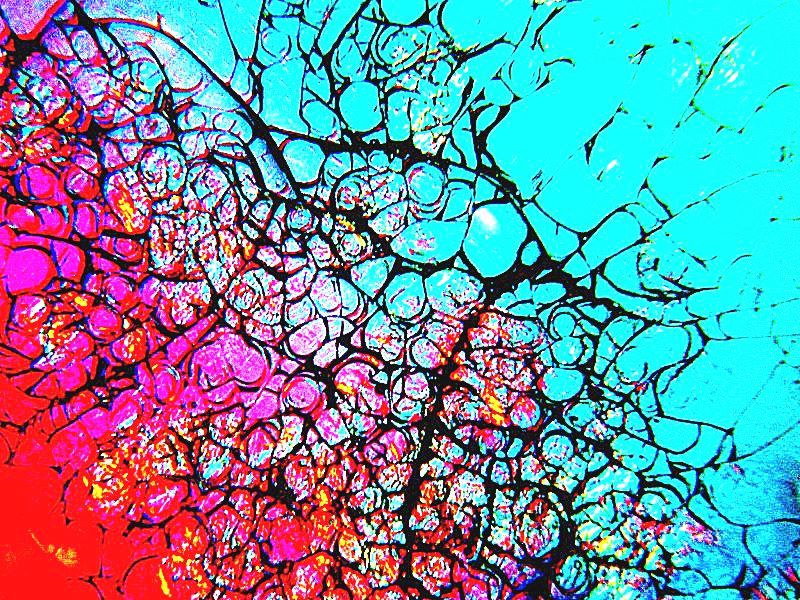

Another display of hexagonal (and sometimes pentagonal) forms is to be found in the freshwater alga Hydrodictyon. There are a number of species and a species introduced to New Zealand has become intrusive. The image of the species shown below demonstrates the branching, almost dendritic, character of certain types.

The background colors were achieved with a combination of oblique and Rheinberg illumination.

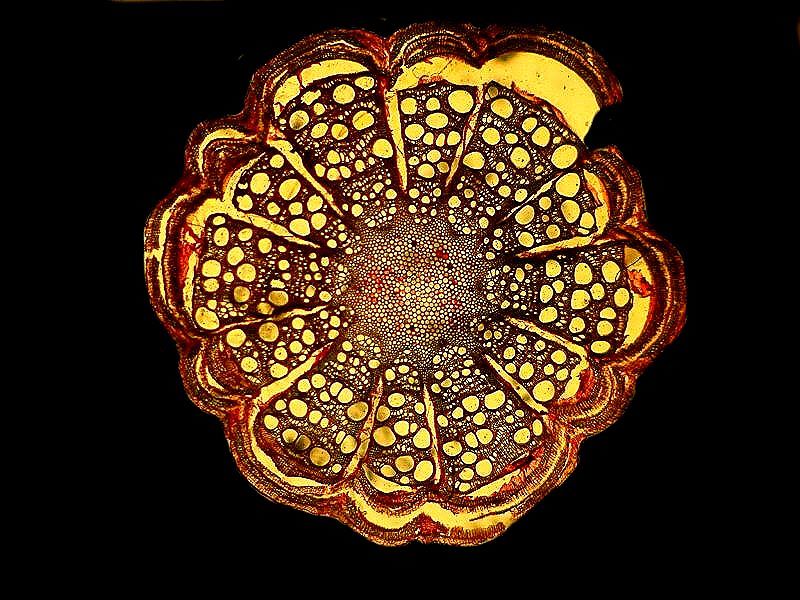

Some forms in nature are so distinctive as to be unforgettable, especially if one has tried to make ones own slide preparations of them. A case in point is cross sections of sea urchin spines. The nightmare of making such preparations is that the procedures are complex, complicated, repetitive, tedious and, if at any stage, one gets careless or simply has bad luck, a specimen can be ruined and hours of work lost. However, successful preparations are splendid and “a joy forever”. Large spines tend to be heavy and compacted and the sections are dense with calcareous material. Smaller spines tend to be less dense and, as a consequence, reveal the crystalline structure of the spine more readily by allowing us to see the spaces between the crystalline areas very clearly and unmistakably.

These interstices are essential, since they reduce the weight; a completely solid spine would be unwieldy and grossly inefficient, although as we know Mother Nature is not always efficient

Nature is full of creatures benefitting at the expense of other creatures ( and I’m not just talking about Wall Street bankers), some of them through predation, but many as parasites (like politicians). Here is an image of 2 lice that remarkably were removed from a live wolverine, granted, in a zoo, but nonetheless, not a task I would want to undertake.

Clearly, these are 2 healthy specimens who are thriving in the association with the ill-tempered and ferocious beast.

We want the same sort of assurances regarding accurate information and the trustworthiness of the person presenting the material to us whether the subjects be microscopic or macroscopic. Let me conclude the image section of this discussion with 2 more examples, this time with macroscopic images and rather impressive ones.

First off, I’ll show you 2 images of a relatively uncommon and little studied coral that was first described by Hirchenfeld in 1826 in a collection from a German expedition. The vase-like appearance in the side view is striking enough, but the 5 apertures visible from the top have provoked much speculation regarding the kind of polyps that extend from them. Samples of these organisms have been obtained only through deep sea dredging and all of the soft tissue has always been so badly damaged and distorted that the appearance of the polyps remains a matter of speculation and further research.

First here is an image of the side view of the “vase” which has an elegant simplicity.

And then the image of the top view with it’s 5 open apertures allowing us to get glimpses down into the “vase”. I was fortunate enough to obtain this specimen through a friendship which developed with Dr. Holz Heinhauer, whom I met at a conference in Leipzig when I was doing research in philosophical biology one year.

The last image for this section is one provided to me by a former student, Mark Jenkins, who is a traveler and adventurer and cycled across Russia from Vladivostok to Moscow and wrote about the trip in Off the Map: Bicycling Across Siberia. He also went down the Niger river and wrote To Timbuktu: A Journey Down the Niger. He has climbed many mountains, including Mt. Everest before it was a tourist fad. He is a contributing writer of the National Geographic Magazine. On one of his trips, in Peru, he came across a stunning tribal mask and brought it back to Laramie and kindly presented it to me. I took some photos of it and I’ll share one with you here. The basic primitivism and the striking color contrast, along with the thoughtfulness of the gift, have made this one of my prized possessions.

Now, you may wonder why I was making such a fuss about the issue of trust. Originally, I titled this article DECEPTIONS, but then I decided that I didn’t want to give things away too quickly. I felt it was important to set the stage to show just how crucial this issue is. All of the 9 images above are misdescribed and were intentionally designed to mislead you. Oh, I can already hear your howls of protest: “I was fooled for a second.”, “Of course, I knew these were deceptions; they were so obvious.” Well, good for you. But in case there were one or two of you who were taken in, I’ll give you a brief tour telling you what the images really represent.

1) The first image that was supposed to be spider eyes is in fact bubbles. I was attracted to the grouping precisely because they did indeed look like eyes.

2) The image that was supposed to be a feather was in fact a radula from a mollusk, but there were distinctive resemblances which led me to represent it as a feather.

3) The third image is a bit trickier and the forms are indeed suggestive of diatoms, but these are, in fact, pollen grains. Isn’t Nature grand?

4) What is purported to be Hydrodictyon isn’t organic at all, but is a mixture of the sweetner (well, that might be regarded as organic, if you want to pick nits) and Ascorbic acid. And regarding the illumination, I’m no longer sure just how I achieved it; it could have been filters or simple polarization.

5) The cross section of the sea urchin spine is in fact a cross section of a plant stem. What appear to be the interstices between “crystals” are actually vascular tubules for transporting fluids up to various parts of the plants.

6) These are indeed lice and photographed from a 19th Century slide. However, it is highly dubious that they were obtained from a wolverine.

7) and 8) This lovely coral “vase” is first the side view and then the top view of a large and wonderful Aristotle’s lantern from a sea urchin. This is the fascinating structure which supports the muscles which slide up and down and produce the scraping movement of the 5 teeth.

9) This splendid mask is in fact an image of the back of a beetle and the first time I saw it, I knew that it had to be incorporated into an article as some kind of tribal mask and so here it is.

Well, so much for trust! How do you know that my second set of explanations are to be trusted? I may be prevaricating again. I can offer you assurance that I am not and that what I have given you in the second account is indeed the truth. When I give you my word, I’m as trustworthy as Honest John, your local used car dealer.

Now that I’ve perpetrated my prank, it’s hard to restore confidence so that you will once again believe me.

Science and knowledge in general have a great deal to do with trust. When we read an account of an historical event, we have an expectation that we are being given a set of facts or, reasonable interpretations, of data that can be substantiated. However, such trust depends very much on the person involved in presenting the account. Especially with regard to historical events, we can expect bias depending on the author. If we read an account of World War II by someone who was an enthusiastic member of the Gestapo, we can anticipate propaganda, fact-bending, omissions, and distortions. A neo-Nazi might make the very same charge against Churchill’s account of WW II. Who one sides with as having the “truth” is often a matter of cultural perspective, the extent of ones access to information, and, in the case, of conflict, who won and who lost. Or, as one wit put it, after listening to two accounts of an automobile accident in court testimony, “I now doubt all history.”

Science, however, is supposed to be different, in that it is based on facts. That issue opens up a Pandora’s box. Well, we all know a fact when we encounter one–right? Well, not according to D.J. Trump and his cohorts who claim that there are “alternate facts.” However, that nonsense apart, there are plenty of problems about the concept of facts.

1) It is a fact that there are no unicorns. Here we run into the thorny thicket of trying to prove a negative. A critic might ask if you have looked in all the places where there might be unicorns?–the wildest areas of Borneo, the hidden valleys in the Amazonian Basin, the lush, dense rain forest of southern China? Not to mention planetary systems in the Andromedean galaxy; you haven’t looked there! So, there!

I might respond by telling you that unicorns are mythic beings created by inventive human minds. You might counter that what if in the years prior to 1798, someone had claimed that there existed an animal with a body like a beaver, with a broad flat tail, a bill like a duck, and that it layed eggs, was covered with fur, lived in the water, and that the male had venomous spurs on its hind legs. Also, since it’s reportedly found in Australia, you might well accuse me of having one or two or three too may Jagerbombs, an alcoholic abomination. However, they were discovered, platypuses, that is, not Jagerbombs, in 1798-99. And as it turns out duck-billed platypuses , fortunately and wonderfully exist and are now a protected species.

So, it is a fact that these marvelous creatures exist. (Maybe they were raised by unicorns.) One of my favorite examples is one used over and over by logicians, namely: “All swans are white.” It wasn’t until the end of the 17th Century that Europeans encountered black swans and prior to that time, they were regarded as “mythic’, since everyone “knew” that “All swans are white.”

So, knowledge is a living, developing “thing”, but that doesn’t mean that we can just arbitrarily out of psychological need, religious reassurance make up “facts” or principles (or beings) of explanation. Bishop Berkeley got that much right; if we can’t hear, see, touch, smell, or taste it, then we are not is a position to say that “it” exists. However, we do need to add a crucial extender. We can also assert the possible existence of certain kinds of “entities’ on the basis of careful reasoning from what we do hear, see, touch, smell, or taste provided that the experience is repeatable and can be confirmed by multiple observers. Think of the electron. We cannot “see” one in principle, because in order to illuminate the electron we would need a source that is a ½ a wavelength shorter and, as far as we know that this point, no such source exists.

Now, we have handfuls of sub-atomic particles with all sorts of weird properties and then the even stranger quarks and yes, one of them is named “strange”. As the oddness escalates, so does the dependence on esoteric, abstract mathematics and, as a consequence, the ontological status of the “deduced entities’ becomes “thinner”; that is, more remote from any direct sensory encounter. And, at the other end of the scale, there are “blackholes”, “cosmic singularities”, “dark stars”, etc. This seems to place human knowledge in a highly precarious situation.

The knowledge that we have amassed is so overwhelming and yet relatively so little and in the long term insignificant. This means that we need to recognize that knowledge is “organic”; it is something that develops and changes and we are constantly in the process of refining and expanding it. Knowledge and facts are, after all, human inventions and though it may seem very odd to assert the following, it is nevertheless the case. The odd assertion is this: Prior to the end of the 17th Century, black swans did not exist. No human had encountered one, so no existential judgment could have been made. So, that black swans did not exist is true in a foundational sense and not merely in a contingent sense. So, even if 50 Australian aborigines knew of black swans, had seen them, that did make them part of the community of knowledge and thus there were only 50 people for whom black swans existed.

Let me take an even more provocative example, malaria. Malaria has been recognized since ancient times and its very name “bad air” tells us much, for it was thought that noxious air from swamps could cause the illness. Of course, no one had the slightest inkling that a microscopic organism, Plasmodium, was the real cause and (boldly I assert), Plasmodium did not exist until 1880 when it was discovered in the blood of malaria patients by Laveran. At that point, we can, of course, retroactively say, mais oui, Plasmodium existed inthe time of Hippocrates and Galen, but they couldn’t have known that or anything about it being a couple of thousand years shy of the invention of the microscope.

We, as humans, are limited by a number of factors in terms of our access to “reality”. Our most powerful tools are our senses and our brains and nervous systems which do the information processing. By using our brains creatively, we have been able to accomplish extraordinary feats by expanding and extending our senses in a multitude of dimensions. Through very clever experiments and sophisticated instrumentation, we have been able to learn that other animals have access to aspects of reality that are outside of the ranges of our sensors. The number and kinds of examples are staggering; echo-location in bats, ultraviolet vision in insects, the ability of birds to “hear” earthworms crawling along underground, sharks extraordinary ability to detect blood in water over considerable distances, whales capacity to detect the songs of other whales many miles away, the ability of lizards to strike and capture prey with such rapidity that we need special apparatus to record and observe it, and the list goes on and on.

What we call reality is a radically dynamic system of judgments and some individuals can live quite successfully and contentedly with a very limited concept and knowledge of “reality”. Others want enough more understanding to be able to fulfill often elaborate ambitions and then there are the extreme cases like Faust: “Zwar weiss ich viel, doch mcht.’ ich alles wissen!” (Indeed, I know much, but I would know all!) A passion to be omniscient, to fully grasp reality in its completeness and richest totality. To me, a being who could achieve that is unimaginable (given the name of God, I believe), which is, I suppose, why I am an atheist.

So what can we conclude from all these rambles?

1) Knowledge and what we call Reality are dynamic systems.

2) As our consciousness evolves, we understand the cosmos and nature in ever more substantive and sophisticated ways while realizing that this is an endless process.

3) And in case, we get too proud of our achievements, there is Nietzsche’s reminder:

“In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering among innumerable solar systems, there was once a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the most mendacious minute in ‘world history’–yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star grew cold and the clever animals had to die.”–On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense.

4) Finally, never trust a philosopher.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the November 2019 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .