DESMIDS & OTHER ALGAE -

PRIMARY PRODUCERS in the FOOD CHAIN

by William Ells

Coniferae, Walnut Tree Lane, Loose, Maidstone, Kent. ME15 9RG. UK.

I

suggest invertebrates feeding on algae is a good field of study for amateur

microscopists, even those of us with little experience. As you read 'MICSCAPE'

I assume you already have a microscope or are about to acquire one. With

a 10:1 objective to search a slide, (do get a mechanical stage if you can

afford it, it makes searching much easier) a 40:1 for detailed examination,

a 10:1 eyepiece, a few slides and cover glasses, a live sample from a pond

etc., boggy places and moss squeezings are best for desmids, and you are

in business.

I

suggest invertebrates feeding on algae is a good field of study for amateur

microscopists, even those of us with little experience. As you read 'MICSCAPE'

I assume you already have a microscope or are about to acquire one. With

a 10:1 objective to search a slide, (do get a mechanical stage if you can

afford it, it makes searching much easier) a 40:1 for detailed examination,

a 10:1 eyepiece, a few slides and cover glasses, a live sample from a pond

etc., boggy places and moss squeezings are best for desmids, and you are

in business.

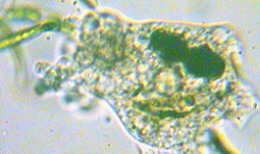

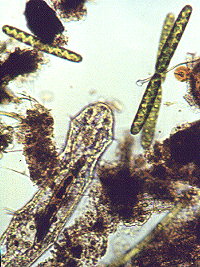

Figure 1. Amoeba eating Closterium.

Take notes of your observations, make sketches of anything

you do not recognise to look up later with measurements if possible (how

this done will be shown later). It is not too difficult to record your

observations with a camera (see earlier article

on photomicrography). Although my main interest is in the desmids I

take note of other algae and its consumers in a sample.

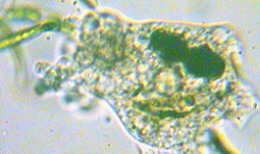

In

1986 I found amoebae feeding on desmids, I sent some photomicrographs to

Alan Brook Professor Emeritus at the University of Buckingham, he made

similar observations of a different amoeba and desmid species, for details

see Brook & Ells (1987). A good example how the amateur can get involved.

Figs 1 & 2 are from the same period.

In

1986 I found amoebae feeding on desmids, I sent some photomicrographs to

Alan Brook Professor Emeritus at the University of Buckingham, he made

similar observations of a different amoeba and desmid species, for details

see Brook & Ells (1987). A good example how the amateur can get involved.

Figs 1 & 2 are from the same period.

Figure 2. Amoeba with ingested desmids

You

may need to study a sample at intervals over a day or two in order to see

what is being ingested, digested and excreted. The method I use is :- Put

a drop of the sample on a slide; spread a thin smear of petroleum jelly

(Vaseline ™) on a spare slide, then drag the edge of a cover

glass along this slide to pick up a continuous strip of the jelly, repeat

with the other three sides of the cover glass, then lower the cover glass

over the sample drop, see Fig. 3 right.

You

may need to study a sample at intervals over a day or two in order to see

what is being ingested, digested and excreted. The method I use is :- Put

a drop of the sample on a slide; spread a thin smear of petroleum jelly

(Vaseline ™) on a spare slide, then drag the edge of a cover

glass along this slide to pick up a continuous strip of the jelly, repeat

with the other three sides of the cover glass, then lower the cover glass

over the sample drop, see Fig. 3 right.

You will need to experiment to get the right size drop of water containing

the specimens and the right amount of jelly on the cover glass. If you

use oil immersion objectives you will find it easier with the cover glass

sealed than with the cover glass floating on a film of water.

After the first examination the slide should be kept in

a cool place, a north facing window sill is ideal, protected from dust

with a watch glass or something similar. You will find algae and protozoa

etc. will keep alive for a week or more using this method. Or you may find

you have bacterial soup or fungal attack renders the sample useless.

I have also kept samples in jam jars (nothing fancy) for

several months dipping into them from time to time. In one such sample

collected from a tarn near the Drunken Duck Inn in the English Lake District

in the company of a group of sober desmid enthusiast on a foray from the

Freshwater Biological Association. The small tarn is not named on my Ordnance

Survey map.

Each mount I examined from the tarn had a few small rods

of compressed debris I knew to be faecal pellets of a small crustacean

or possibly insect larvae. Macerating the pellets on one of these mounts

by applying pressure and a twisting motion to the cover glass, I identified

large numbers of empty semi cells of the desmid; Staurodesmus triangularis

(Lagerh) Teiling 1967, and two semi cells of Closterium costatum

Corda ex Ralfs 1848.

In the jar containing the tarn sample were two freshwater

shrimps of the genus Gammarus, I removed and examined these under

a low power (35:1) stereo microscope and found one had a pellet in its

anal cavity. After fixing, I removed the pellet, placed it on a slide and

macerated it as before. From this one pellet I found no less than 80 empty

Staurodesmus semi cells, one Euastrum sp. and one Staurastrum.

Note all the ingested Staurodesmus cells were broken at the isthmus

- this agrees with the laboratory experiments carried out by Coesel (1997).

However the desmids ingested by the amoeba were excreted with the cell

wall intact, the protoplasm apparently being taken up by the digestive

process through the pores in the cell walls.

The shrimps having been in the jar six months had little

choice of diet. I could not find any living

Staurodesmus at this

time, possibly they had all been eaten by the shrimps. Other desmids were

still thriving, mostly Closterium spp. and a few of that handsome

desmid Euastrum verrocusum alatum.

Aquatic oligocheate worms are inveterate feeders on algae,

in water collected from Thursley Common, Surrey on the 21.5.88 and examined

on the 18.7.88 there were several oligocheatae that had been feeding on

two species of

Trachelmonas. One of the worms had ten Trachelmonas

which could be clearly seen in its digestive tract, and there appeared

to be even more in a dense mass within which individual cells could not

be easily distinguished. Trachelmonas is one of several micro-organisms

claimed by both the botanist and the zoologist, the smaller of the two

species consumed, about 21 x 11 µm. and the one in greatest abundance

in the sample, had an ochre coloured lorica with no obvious markings and

a distinct collar. The other was larger 36 x 19 µm. with a paler

colour lorica, a granular surface and a distinct collar. More than a hundred

species have been described in texts on algae and protozoa.

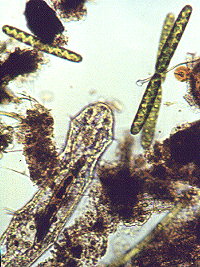

Further

observations made in September 1990 in a sample collected from a boggy

pool near Blair Atholl, Perthshire, oligocheate worms were found that had

been feeding on diatoms and desmids. In one could be seen a diatom of the

genus Surriella, and in another three cells of the desmid Tetmemorus

granulatus. The worms were approximately 1.25mm. long, their head 219µm

broad. The Tetmemorus were approximately 200µm. long by 35µm

broad, so the three were nearly half the length of the worm. The cells

were unbroken, one empty, one nearly so, the other with shrunken chloroplast.

Further

observations made in September 1990 in a sample collected from a boggy

pool near Blair Atholl, Perthshire, oligocheate worms were found that had

been feeding on diatoms and desmids. In one could be seen a diatom of the

genus Surriella, and in another three cells of the desmid Tetmemorus

granulatus. The worms were approximately 1.25mm. long, their head 219µm

broad. The Tetmemorus were approximately 200µm. long by 35µm

broad, so the three were nearly half the length of the worm. The cells

were unbroken, one empty, one nearly so, the other with shrunken chloroplast.

Later in the same year an aquatic oligocheate worm with

a desmid of the genus Closterium in its gut was found in a sample

from Sutherland, Scotland. (Fig. 4. right - note the recently divided cells

of the desmid Spirotaenia condensata). Both these samples were freshly

collected material without the restrictions on diet of the earlier samples.

Lund & Lund (1995) show part of an oligocheate worm with a desmid,

genus Euastrum in its gut (page 275).

In 1997 during examination of a sample of water from Dartmoor,

I found a rotifer that I now know to be Tetrasiphon hydracora, in

its stomach could clearly be seen among a green mass a desmid of the genus

Micrasterias. I sent a drawing of the rotifer to Mr. Eric Hollowday

who identified the animal for me, I quote from his letter :-

' This animal is a real "desmid cruncher" to be sure!

Rus Shiel of Australia showed a remarkable video in Poland three years

ago showing it crunching and munching its way through one desmid after

another with astonishing speed, the trophus seems to be excellently adapted

for this purpose, so keep it out of your cultures.'

This rotifer is probably rare, fortunately for the desmids,

it is the only time I have seen it, Eric Hollowday a rotifer specialist

tells me he has seen it alive only once, from Thursley Common.

I understand that in Japan a species of algae is cultivated

to feed the specially bred rotifers of the genus Brachionus which

in turn are fed to fish fry for the ornamental fish market.

I have seen in a video by Mike Dingley a Heliozoan with a desmid

, genus Cosmarium impaled on one of its spines (axopodia) we do

not know if it is ingested or not.

In spite of all these observations there is still plenty

of work for the amateur. Are there other rotifers that actually take in

alga cells, we know there are some that feed by sucking out the protoplasm?

Do protozoa feed on algae they chance upon, or are these primitive animals

able to select their prey? Do some species of aquatic worms prefer diatoms

to desmids? Why not share anything you discover with us? Send a description

of your observations with a photomicrograph if possible to the Micscape

Editor for possible publication.

Acknowledgements:-

The author is indebted to Eric Hollowday for identifying

the rotifer and for his helpful comments. Thanks to Faith Coates for the

excellent sample from a bog on Dartmoor.

References:-

Brook A.J. & Ells W. (1987) The Feeding of Amoebae

on Desmids. Microscopy Vol. 35 Part 7. pages 537-540. The Quekett Microscopical

Club.

Brinkhurst R.O. (1963 revised 1971) Aquatic Oligocheata.

F.B.A. Pub. No. 22.

Coesel P.F.M. (1997) The edibility of Staurastrum chaetoceras

and Cosmarium abbreviatum (Desmidiaceae) for Daphnia galeata/hyalina

and the role of desmids in the aquatic food chain. Aquatic Ecology 31:

pages 73-78. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Jahn T.L., Bovee E.C. & Jahn F.F. (1949) How to know

the Protozoa. Wm. C. Brown Pub. Dubuque Iowa.

Lund H.C. & Lund J.W.G. (1995) Freshwater Algae. Biopress

Ltd. Bristol. England.

Editor's note: Comments and feedback via email

to Bill Ells

are welcomed.

Please report any Web problems to the Micscape

Editor, via the contact on current magazine index.

First published in Micscape Magazine, May 1998 ( ISSN 1365 - 070x )

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK Web

site at http://www.microscopy-uk.net/mag/indexmag.html

WIDTH=1

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights

reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net.

I

suggest invertebrates feeding on algae is a good field of study for amateur

microscopists, even those of us with little experience. As you read 'MICSCAPE'

I assume you already have a microscope or are about to acquire one. With

a 10:1 objective to search a slide, (do get a mechanical stage if you can

afford it, it makes searching much easier) a 40:1 for detailed examination,

a 10:1 eyepiece, a few slides and cover glasses, a live sample from a pond

etc., boggy places and moss squeezings are best for desmids, and you are

in business.

I

suggest invertebrates feeding on algae is a good field of study for amateur

microscopists, even those of us with little experience. As you read 'MICSCAPE'

I assume you already have a microscope or are about to acquire one. With

a 10:1 objective to search a slide, (do get a mechanical stage if you can

afford it, it makes searching much easier) a 40:1 for detailed examination,

a 10:1 eyepiece, a few slides and cover glasses, a live sample from a pond

etc., boggy places and moss squeezings are best for desmids, and you are

in business.

In

1986 I found amoebae feeding on desmids, I sent some photomicrographs to

Alan Brook Professor Emeritus at the University of Buckingham, he made

similar observations of a different amoeba and desmid species, for details

see Brook & Ells (1987). A good example how the amateur can get involved.

Figs 1 & 2 are from the same period.

In

1986 I found amoebae feeding on desmids, I sent some photomicrographs to

Alan Brook Professor Emeritus at the University of Buckingham, he made

similar observations of a different amoeba and desmid species, for details

see Brook & Ells (1987). A good example how the amateur can get involved.

Figs 1 & 2 are from the same period.

You

may need to study a sample at intervals over a day or two in order to see

what is being ingested, digested and excreted. The method I use is :- Put

a drop of the sample on a slide; spread a thin smear of petroleum jelly

(Vaseline ™) on a spare slide, then drag the edge of a cover

glass along this slide to pick up a continuous strip of the jelly, repeat

with the other three sides of the cover glass, then lower the cover glass

over the sample drop, see Fig. 3 right.

You

may need to study a sample at intervals over a day or two in order to see

what is being ingested, digested and excreted. The method I use is :- Put

a drop of the sample on a slide; spread a thin smear of petroleum jelly

(Vaseline ™) on a spare slide, then drag the edge of a cover

glass along this slide to pick up a continuous strip of the jelly, repeat

with the other three sides of the cover glass, then lower the cover glass

over the sample drop, see Fig. 3 right.

Further

observations made in September 1990 in a sample collected from a boggy

pool near Blair Atholl, Perthshire, oligocheate worms were found that had

been feeding on diatoms and desmids. In one could be seen a diatom of the

genus Surriella, and in another three cells of the desmid Tetmemorus

granulatus. The worms were approximately 1.25mm. long, their head 219µm

broad. The Tetmemorus were approximately 200µm. long by 35µm

broad, so the three were nearly half the length of the worm. The cells

were unbroken, one empty, one nearly so, the other with shrunken chloroplast.

Further

observations made in September 1990 in a sample collected from a boggy

pool near Blair Atholl, Perthshire, oligocheate worms were found that had

been feeding on diatoms and desmids. In one could be seen a diatom of the

genus Surriella, and in another three cells of the desmid Tetmemorus

granulatus. The worms were approximately 1.25mm. long, their head 219µm

broad. The Tetmemorus were approximately 200µm. long by 35µm

broad, so the three were nearly half the length of the worm. The cells

were unbroken, one empty, one nearly so, the other with shrunken chloroplast.