|

Adventures in the Berlin Tiergarten

Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

I visited the Berlin Tiergarten (literally “Animal Garden” or in other words “Zoo”) 50 years ago while waiting for a visa to go into East Germany to do research at the Goethe-Schiller Archive. I was exasperated with the Kafkian bureaucratic red tape of the East Germans and needed to relax and unwind.

Before I left the U.S., the State Department had sent me some information on East Germany, including the address of the Visa Office in East Berlin. Before leaving West Berlin, however, I decided to call the U.S. Consulate to confirm the address and yes, I was assured that the Visa Office was on the Friedrichstrasse.

I took the subway line over to the Friedrichstrasse station in East Berlin and there went through the checkpoint. West Berliners had to be very careful not to take that subway line into East Berlin, because at that time West Berliners were forbidden entrance to East Germany and a simple mistake could result in several days of detention and interrogation. Each time one crossed the border, one was required to fill out customs and currency declarations and have ones luggage searched. Then, assuming that there were no complications, one was given a permit for the day to remain in East Berlin, which meant that one had to be back in West Berlin by midnight. On entering, one also had to convert a minimum amount of currency into East German marks and it was strictly forbidden to take any East German currency in or out. So, of course, one had to spend whatever one converted, which is a nice way of boosting any economy. I went to the address I had been given and climbed two flights of stairs to the offices of a small travel bureau. The only person working there at the time was a young woman, who knew no English, and was trying to talk to a middle-aged American couple who knew no German. They were trying to get a visa to visit Dresden and I was trying to get one for Weimar. Since I could speak some German, I offered to help, but the young woman knew nothing about visas. Finally, I prevailed upon her to call to find out where the Visa Office was. After an extended telephone conversation, she rather anxiously suggested that we go to the Police Presidium. This clearly did nothing to calm our nerves, but the three of us took a taxi to the Police Presidium in the Hans Beimler Strasse, a considerable distance from the Friedrichstrasse. As it turned out, the Visa Office was indeed located in the Police Presidium and I helped the American couple get their visa for Dresden. I then turned to the task of getting my own visa and was informed that the relevant papers of my visa had not yet arrived from Weimar.

That was the first of five trips to get a visa. Each day I had to be out of the East zone and back into West Berlin by midnight. After the third trip, I got tired of going through the checkpoint and filling out custom and currency declarations, so I got the telephone number of the Police Presidium and went back to West Berlin, waited two days, and then put in a call from the hotel. I was amazed at how stupid I had been. Instead of all this travelling back and forth, why had this simple idea of calling not occurred to me before? Seven hours later the telephone call was returned to inform me that the paper had still not arrived. I later discovered that, at that time, there were only fourteen telephone lines linking East and West Berlin. By that time, I was beginning to feel like a character caught in the middle of a Kafka novel. I was beginning to think that the U.S. State Department didn't want me to go, since they kept giving me the wrong address. I was also beginning to think that the East Germans didn't want me to visit, since no one seemed to know anything about the papers. The next morning, I decided to take more decisive action. I packed everything and again set out for the Police Presidium. I patiently explained to a police official that I had been waiting for over a week for the papers for my visa. He made a phone call and then suggested that I get a 24 hour visa, take the train to Weimar, and have the police in Weimar issue the visa for the period of my stay. That afternoon, I arrived in Weimar. Now Weimar has for centuries been a great intellectual and cultural center of Germany and in 1975 celebrated the 1000th anniversary of its founding. Johann Sebastian Bach lived there briefly, Goethe's house is there as well as a Goethe Museum, Schiller's house, Franz Liszt's house, the Nietzsche villa, and Lucas Cranach, the painter, Rilke, the poet, Herder, Thomas Mann had all lived in Weimar for a time. There are castles, archives, parks, museums, libraries, and institutes, all under the jurisdiction of an administrative unit with a title that only the Germans could have invented—die Nationale Forschungs-und Gedendstätten der klassischen deutschen Literatur in Weimar—known as the NFG, for short. The story is told that during the period when Hitler was trying to "purify" the German language and get rid of all foreign derivatives, the word "Dynamo", which means the same thing that it does in English, got replaced by "Wassertreibselektrizitätsherstellungsmaschine"! This is sometimes offered as an explanation of the German defeat.

So, there I was in Weimar. I jumped into a taxi, certain that everyone in Weimar would know where such a prestigious institution was located and said confidently to the driver: "Take me to die Nationale Forschungs-und Gedenkst a tten der klassischen deutschen Literatur in Weimar." He turned around and looked at me in total bewilderment as though I had asked to be taken to Mars. I then asked to be taken to the Nietzsche Archives and was again met with puzzlement. Finally, I started to explain about archives and institutes and libraries and castles and when I hit on castles, he said, "Ah, ja! You want to go to the Castle." Now, I really did feel like I was in the middle of a Kafka novel.

As it turned out the main administrative offices for the NFG were indeed housed in the Castle. My arrival created consternation. Professor Holtzhauer, the director, was on vacation and so, his secretary called Dr. Hans Henning, Director of the Central Libraries, who appeared a half an hour later. I explained the visa problem to Dr. Henning, who helped me find a hotel room for the night. The next morning, Dr. Henning picked me up in his car at the hotel and we went off to the police in Weimar to settle the visa problem, or so we thought. Armed with official documents which had not yet been sent to East Berlin, since my arrival date had not been known, we expected every success. A police official listened patiently and then abruptly informed us that visas could be issued only in East Berlin and that I would have to be out of East Germany by midnight. And so I returned by train to East Berlin, crossed back over to West Berlin, waited two days and then packed everything up again and returned to the Police Presidium in East Berlin to get my visa. I arrived to be once again informed that the official papers had not yet arrived. By that time, exasperation had overcome prudence and I lost my temper. I informed the police official that this visit was a result of an official invitation from the East German Ministry of Culture. Ten minutes later I had, in my sweaty hand, an unrestricted visa for four weeks, which meant that I could travel almost anywhere I wanted in East Germany without supervision. Nietzsche despised the bureaucratic machinations of political systems and, in fact, gave up his German citizenship and never took citizenship in another country. From that time on, he described himself, not according to nationality, but as a European. Nietzsche travelled from Germany to Italy to Switzerland to France and now in this day of passports and visas and residence permits, I very keenly felt the irony of having to go through all of this bureaucratic red tape in order to get to Weimar to study the manuscripts of this philosopher without a country.

So, what does all of this have to do with the Berlin Zoo? Well, during the waiting periods, I found comfort and companionship with the animals there. I think it was the 125th anniversary of the founding of the zoo. (My secret agent, Monsieur Google tells me that it was in 1969.) Zoos can be awful places and many an animal has lived out an utterly miserable existence simply to gratify the idle curiosity of us humans. The great German poet, Rainer Maria Rilke (how could one have such a beautifully alliterative name and not become a poet?), wrote a powerful poem expressing the terrible things that we can inflict upon animals by caging them. Rilke had gone to Paris and was suffering a writer’s block. He became secretary to the great French sculptor, Auguste Rodin. When he told Rodin of his difficulty, Rodin advised him to go to the zoological gardens and to write about specific, concrete entities. Out of this period came one of his most famous poems The Panther in which he captures the sense of this noble beast trapped and condemned.

Here is a site where you can find several different translations of this poem. My preference is for the very last one by C.F. MacIntyre.

In the last few decades, major zoos have undergone significant modifications. They are no longer just rows of prisons to exhibit strange animals to the curious. Many have become research institutions and are desperately trying to breed endangered species, study the diseases and parasites that their animals are subject to, and even collect DNA samples in the rather forlorn hope of eventually being able to restore specific creatures should they become extinct. In addition, many zoos have spent large sums of money to simulate the habitats of various groups of animals which allows them to live in a more natural environment. This means that they live a better existence than they used to in zoos and also such contexts allow them to behave more naturally which can provide researchers with important information. The most important issue is that some major zoos are being transformed into genuine scientific institutions. People like Gerald Durrell and Bernhard Gzrimek, just to mention two, have made enormous contributions to transforming the very concept of a zoological garden—Gerald Durrell with his National Trust on the Isle of Jersey and Bernhard Gzrimek at the Frankfurt Zoo. Such undertakings are very expensive and as long as human beings persist in waging war on each other and everything around them, then large numbers of organisms which share this planet will be at risk of extinction. There are also still those trophy collectors who want to go out and slaughter a rhinoceros, chop off the head, and hang it on the wall of their den. If I could afford to have a den, I would adorn its walls with the heads of “Great White Hunters” and also those of various and sundry politicians.

What does all of this have to do with my meditative respites at the zoo? Well, I’m going to tell you about the okapis and capybaras. Okapis are simply splendid animals which look rather like a cross between a zebra and a large antelope but the males have only short horns which are covered with skin. These animals are actually the only living relative of the giraffe. They don’t have the long neck of the giraffe, but have long blue tongues–long enough to wipe their eyes, wash their ears, and bend branches down to reach the leaves and buds which they eat. The Berlin zoo has benches conveniently situated for weary observers to sit at various strategic points and view specific compounds (provided, of course, that one’s view isn’t blocked by crowds of watchers standing at the rails.) I would usually visit the okapis in the very late afternoon when the keepers were trying to cajole them into the building where they would be fed. As it turned out these okapis were very playful and they led the two keepers a merry chase. Just as one of them seemed to be going into the building, it would bound off and the other okapi would join its mate and the two of them would give a goading look as though saying: Come on, let’s play some more.” This game could go on for 10 or 15 minutes and finally the okapis would tire of the fun and enter the building. Our anthropocentrism sometimes leads us to forget that humans are not the only animals who like to play. Of course, we can observe it in cats and dogs, but if we pay attention to animals in the wild we can also see what indeed seems to be play even though some such behaviors may also be associated with learning survival skills or with courting behaviors. When one observes otters frolicking, it would be hard indeed to believe that they are not playing and having an enormously good time.

Here are two photos (from Google) of Okapi; the second one shows one feeding.

My fascination with the capybaras was of a quite different character. They are the largest living rodents and can weigh up to 140 pounds. They strike me, with their large soulful eyes, as contemplative, even philosophical, creatures. Two of them would come up near the railing on which I was leaning and they would look at me and I would look at them and we would have a silent dialogue. They strike me as quite docile beasts, but I don’t think they would make very good house pets. One would require quite a large shovel to clean up after them. Nonetheless, people do have them as pets. They are very gentle creatures and tolerate birds, other small animals, and small capybaras riding on their backs. They derive benefit from the birds who feed on the insects that have taken up lodging in the capybara’s hair. They spend much of their time in water, are powerful swimmers, but are also quite fast on land.

I’ll show you four images (from Google) of these wonderful creatures. The first gives you a general idea of its size and shape.

The second shows one peering over the edge of someone’s swimming pool.

The third show you what is likely someone’s pet and clearly it is a gentle creature.

And, the fourth photo, shows you the wise visage of an ancient sage.

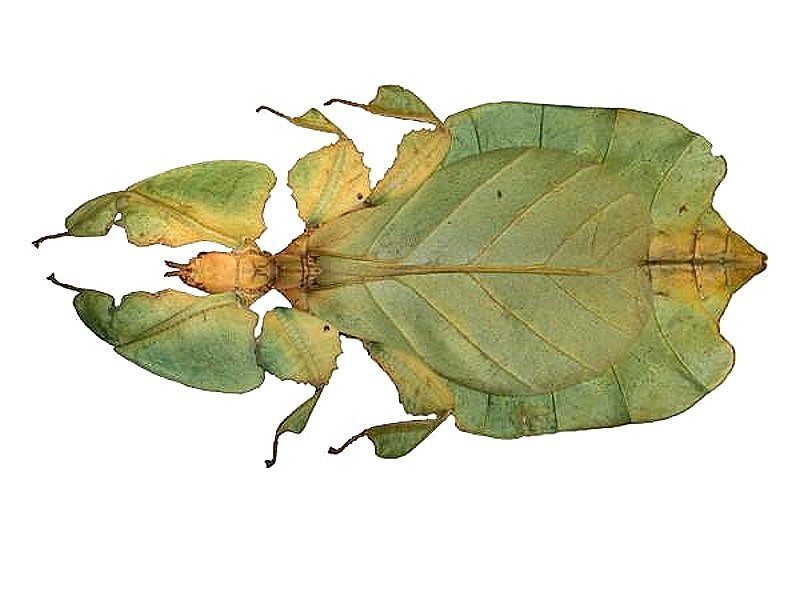

One afternoon, I was walking around the zoological gardens and I noticed a building I hadn’t yet visited which, as it turned out was the Berlin Aquarium which also has an insectarium. I found some large glass cases on the second floor, which would be our third floor, no wonder the world is so confusing, and I wandered over to one of the cases which contained a leafy bush or miniature tree–whatever. I strained my eyes to see what was in the case, I walked around it 3 times–a bunch of leaves–boring as dust. What was I supposed to be looking for? Aphids? Plant mites? In that case, they should have provided me with a magnifier! I was standing there staring at this disappointing case, when suddenly I noticed a slight movement, but it was just a little breeze making the leaves move. But, wait a minute, this was a glass case; there shouldn’t be any zephyrs gusting though it. There it was again, another leaf moved and I suddenly realized that I was looking at a tree branch occupied by some of the most remarkable camouflage artists in all of nature–leaf insects. Take a look.

The first looks like a dried up brown leaf that one might find in autumn after the color had all bleached out of it.

The second is quite like the first but, in this case, a nice healthy green like we might expect in midsummer.

And, the third, is an image of a stick insect. These are remarkable creatures and vary in size from a tiny half-inch species from North America to a species from Borneo that has a torso about a foot long and when the legs are extended is over a foot and a half in length.

Wandering around the Tiergarten was also a wonderful adventure in terms of the lovely gardens and exotic plants. All of this provided me a partial escape from the annoyance and stress of dealing with the East German bureaucracy. Another thing that helped was a very nice restaurant located right outside one of the entrances to the Tiergarten. It was 2 levels and lots of glass which allowed one to sit and watch the passerby, many of whom were headed to the Tiergarten. The restaurant was an island of delight, because they offered everything from a bracingly strong cup of coffee, pastries, sandwiches, complete meals of sausage and salad, or beef, chicken, or pork dishes, and good German beer and very nice house wines. However, perhaps the best part, was that one could take a paper, magazine, or book and sit for two hours and no one would disturb you or suggest that you should move along.

One day, I stayed and wandered around into the evening in the Tiergarten which is open 24 hours; but the Tierpark or Zoo was open from 9:00 to 6:00. However, this meant that one could wander quietly around the gardens, which were well lit and enjoy the air and soothing odor of the flowers. As I was leaving to go back to my small hotel, I noticed across the wide street, below the city train overpass a number of people standing under the immense concrete pillars that supported the tracks above. As I glanced in their direction, a train clattered over their heads making a thunderous noise. However, what caught my attention was that each of the persons standing there had his or her mouth wide open. It was such a contrast from the gardens I had just left that I was befuddled. When I got back to the hotel, I asked the desk clerk about this strange phenomenon and he said: “Ach, ja, people do this to get rid of their tensions. They go down and wait for the strain to rumble through and then they scream as loudly as they can and no one can hear them. It’s a quite therapeutic experience. I sometimes go there myself after a hard day.”

The next day, after my stint with the okapi and capybaras, I went to the restaurant in the early evening and ordered a full course meal with a small flask of wine. Afterwards, I headed for the pillars under the train tracks and prepared myself. I only had to wait about 5 minutes and there was a great roaring which moved toward me and then engulfed me and I let loose with what was perhaps the most satisfying scream of my life. And afterwards, I thought, East German officials “Watch out! Tomorrow, I am going to Weimar.” And, indeed, I did.

All comments to the author Richard Howey

are

welcomed.

If email software is not linked to a browser, right click above link and use the copy email address feature to manually transfer.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the March 2022 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .