If you like to take small risks with possible payoff of fun or frustration, then hunting for old slides on eBay may be just the ticket if you also know when to exercise restraint and call it quits when bidding. In the past year, I bought 3 small sets of slides and so far, the fun has outweighed the frustration. Now, I'm not talking here about slides with a pedigree from a major mounter offered by a dealer with a sterling reputation who often starts with an asking price of $45 for a single slide. Recently, some specialty slides have been going for between $200 and $400–for 1 slide! Curse you Wall Street amateur microscopists!

Of the 3 sets I bought, one consisted of 5 slides, one of 7 slides, and the most recent of 26 slides. The highest price was for the set of 5 which consisted of cross sections of sea urchin spines–a real bargain at $50.50. Do the math; 1 hour with a cheap psychotherapist costs about $75 and for that you can find some small collections that will include at least one sea urchin spine cross section. The Gemmary often has sets of six slides, including a spine section, and sometimes for less than an hour of therapy. These are objects of great beauty especially under polarized light. So, let me show you a few examples along with one that involves a bit of computer magic to create a multiple image.

The second set of 7 slides was not so satisfying and one of the slides arrived broken as a consequence of poor packaging. Overall, the slides were mediocre and not in very good condition, but digital photography coupled with the extraordinary power of graphics software can still allow one to isolate areas which will produce interesting images.

The third set consisted of 26 slides, only two of which were a complete disaster. I will note, however, that all of these slides were very dirty–calm down, calm down, not in the pornographic sense, just in the ordinary sense of grime, grit, and dust.

Some, in fact, are so grimy that, in the condition of their arrival, it would be difficult even with marvels of modern technology to get any good images. So, how to clean them? First, take a can of air, such as that used for computer keyboard dusting and, holding the slide in a horizontal position, quickly dust off the surface. Then I take a cotton swab and dip it in lens cleaner, squeeze it gently to remove any excess and then gently wipe the cover glass, avoiding as much as possible any contact with the ringing cement, if there is any. Take a second dry swab and using the same circular motion, dry the cover glass; then repeat using a third swab.

Now, I will give you a virtual inventory of this set of slides with a preliminary note that 5 of the slides were mounts of segments of butterfly wings and didn’t have cover glasses and that one slide was a larger than standard size and had mounted on it an entire hellgrammite (about which, more later).

I will present these slides in the random order in which I examined them. However, before I do, I would like to admonish any and all dealers, sellers, or collectors who bind groups of slides together with masking tape or put it on the bottom of a slide to provide a kind of “background” for observing the specimen. This is despicable and masking tape is a relatively recent product which certainly has much value and many good uses but, to those guilty parties I say—KNOCK IT OFF! Don’t use masking tape on slides!! If you put such a slide on the glass stage of your dissecting microscope, even though you have peeled off the tape, the remaining adhesive sticks to the stage making the slide difficult to move and deposits a sticky micro-mess on the stage plate. This means that each slide, so contaminated, must be carefully cleaned on the bottom with a solvent that will remove the adhesive. This is time-consuming and annoying, especially when many of these old slides have already been neglected and stored in conditions such that they are very dirty and may have slight to severe damage to the rings, the labels, and the mountant to begin with. So, even if you’re a risk-taker, I would still caution Caveat emptor! For these 25 slides, I paid the princely sum of $10.50 plus a few dollars shipping, so I wasn’t concerned that I might have to refinance our house.

One of the delights of obtaining such a collection at a reasonable price is the sheer fun of getting them into a decently clean state for viewing, examining the specimens, and then taking some photomicrographs. For me, one of the cardinal rules for the amateur microscopist is to have fun, to enjoy the challenges, and to share one's excitement with others. (Or maybe that’s three rules, but who’s counting?) So, I’ve decided to share this collection with you regarding both its strengths and its weaknesses, but you need to realize that modern graphics programs offer the chance to cheat a bit regarding the weaknesses. (Not that I would do that but, to paraphrase Plato: All philosophers are liars. He said poets but, it applies to philosophers as well.)

So, I have decided to present you with a gallery of images of the slides and I’ll make an heroic effort to keep my comments to a minimum. Keep in mind that the primary goal here was to get decent images and not to restore the slide beyond the necessary work to get a clear image of the specimen where possible.

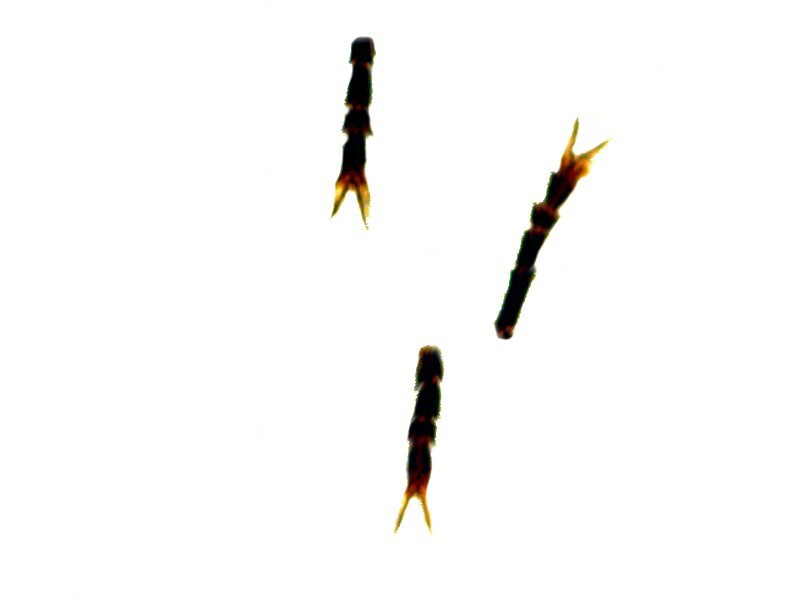

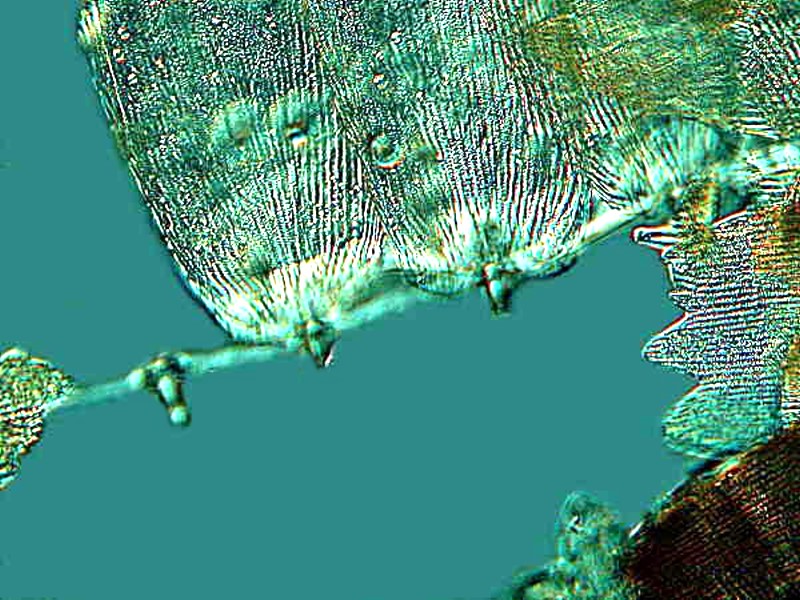

1) Three insect feet.

And a close up of one.

Insect appendages were favorite objects of many 19th and 20th Century mounters. With a bit of practice, they become relatively easy to mount and they are almost invariably morphologically interesting. Just look at all the little hairs on these and the interesting structure of the joints.

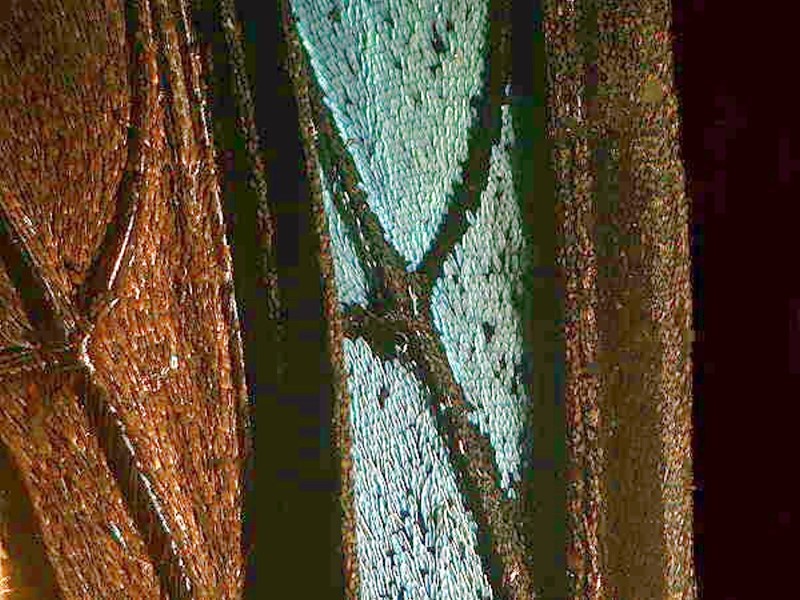

2) Butterfly wing.

Even people who profess an utter disinterest in Nature, have at times been captivated by the splendor of a magnificent butterfly winging past them, for many of them are miniature works of art. Here are 3 closeups of wings from a collection of dried butterflies that I purchased some years ago.

Some, of course, are more spectacular than others, but even some of the drabbest reveal marvels when examined under the microscope. This example in the collection is by no means stunning but, it is, nonetheless, interesting. Here you can see the venation and the scale patterning.

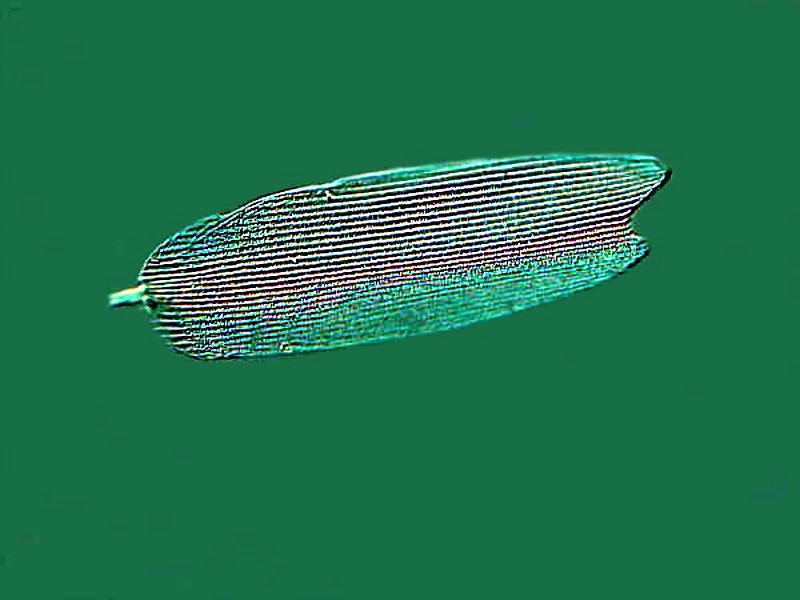

Only a couple of years ago, when I was scraping some scales from a wing, did I discover something surprising, to me at least, about the architecture of these wings. Consider an individual scale.

In looking at it I began to wonder about the function of the terminal rod or projection. I went back, to look again at the wing itself and found something very impressive. The ribbing on the wings is not merely venation. As you likely already know, when a butterfly emerges from its chrysalis, its wings are folded and wrinkled and have to be “inflated”. This is accomplished by pumping fluid into them through the veins and, thereafter, the wings have to sit and dry in order to function and it turns out that these terminal “rods” on the scales are inserted into minute orifices in the ribbing.

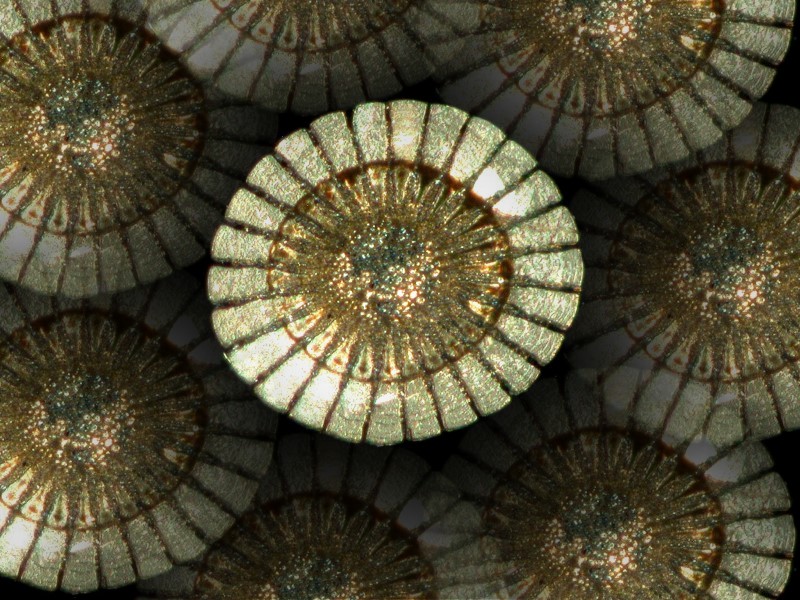

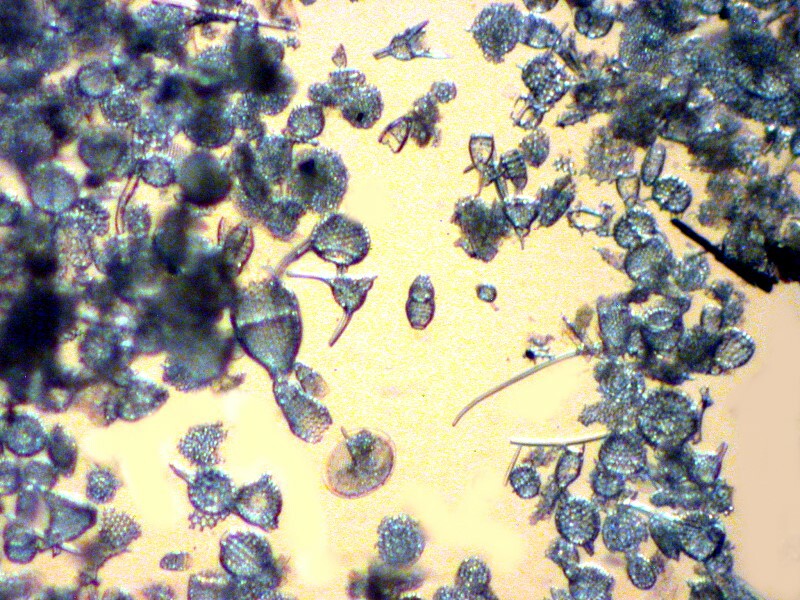

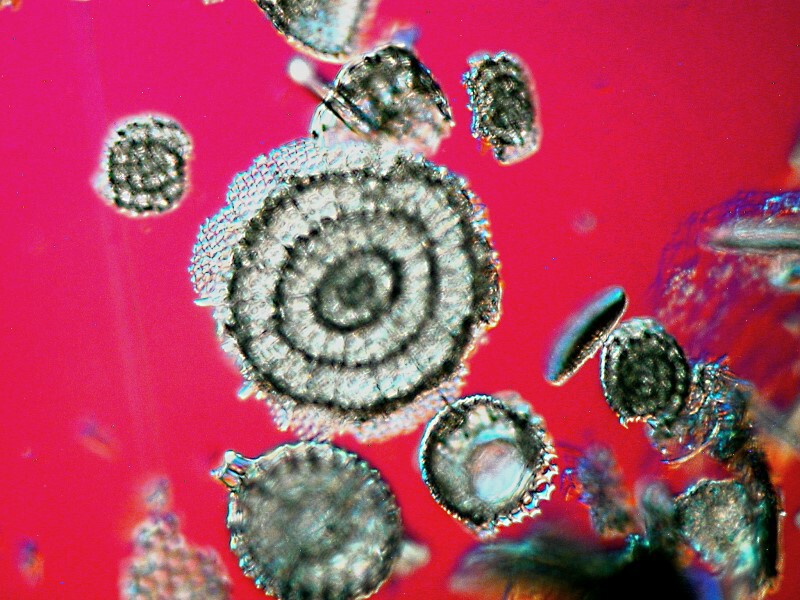

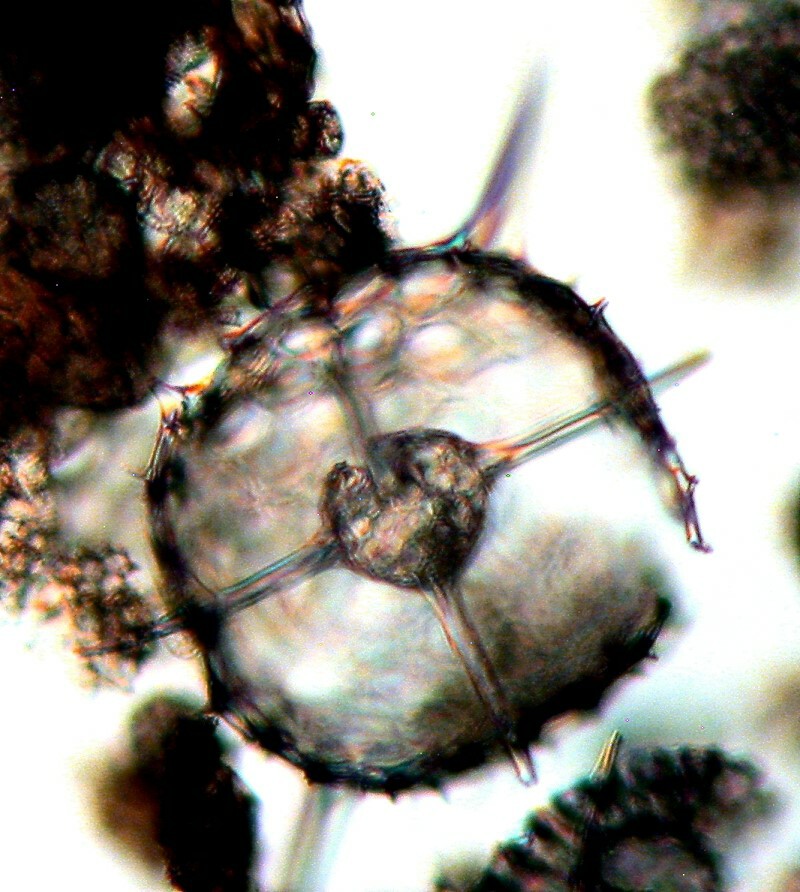

3) Unlabelled, but clearly a strew of shells of radiolaria or as they were called in the 19th and early 20th Centuries–Polycystina.

This is a fair slide with a much too dense concentration of shells and a considerable variety of forms. I would hazard a guess that this sample is probably from Barbados. When so many shells are crowded together, it becomes nearly impossible to get a good view, let alone image, of individual forms.

A couple of closeups are moderately acceptable, but by no means what they could be. These were taken using Nomarski Differential Interference Contrast, but without the use of any stacking software which could improve the images by providing a better 3-dimensional perspective.

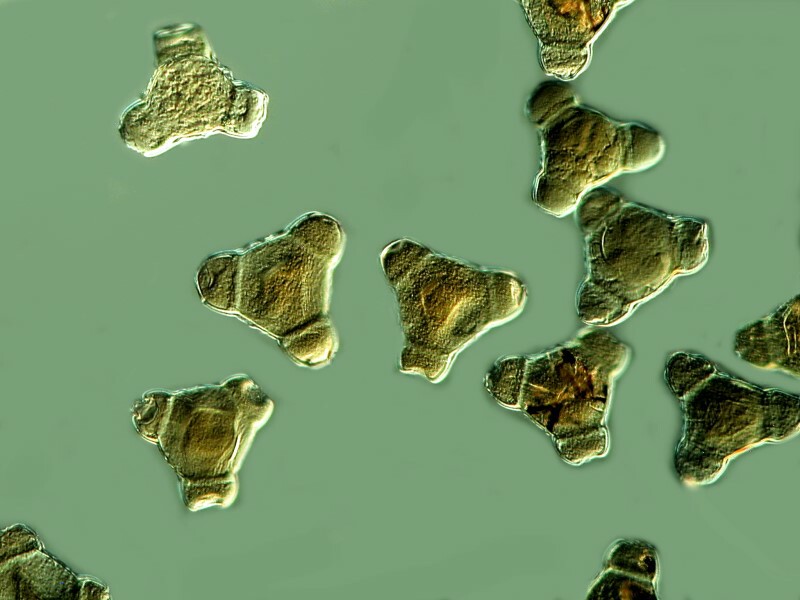

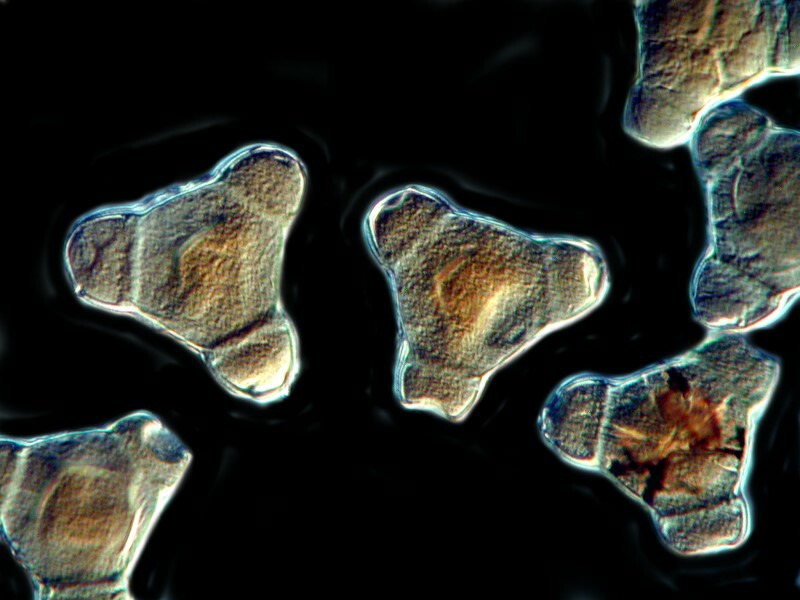

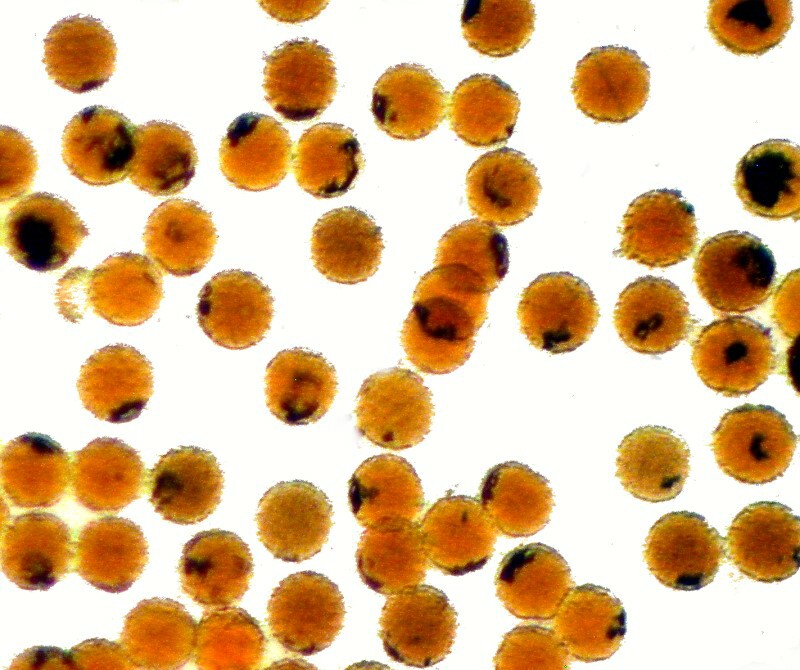

4) Pollen of Evening Primrose. (Oenothera bifrons)

Pollen experts (Pollenographers?) could, I suppose, wax poetic about the objects of their study and fossil pollen does play an important role in paleobotany. However, I suspect that most people think: if you’ve seen one pollen sample, you’ve seen them all. Well, if you think that, this slide should disabuse you of such an attitude. Pollen strews are generally not going to compete with Polycystina or diatom strews but, some are quite lovely, as this slide demonstrates.

And here is a closeup.

In fact, these rather look like diatoms.

5) Ah, the challenge of unlabelled slides!

I am going to make 3 not very educated guesses regarding this slide. 1) It is an insect part. 2) It might be a stinger. 3) It might be an egg case of an insect, since it looks like that extension off to the side might be the top of a capsule. If you have some better guesses, please let me know.

6) No cover glass, specimen lost. At first, I thought it might be a plastic or neoprene ring which would suggest it’s not very old, however, after scratching it with a dissecting needle, I concluded that it’s a glass ring with lots of mountant on it.

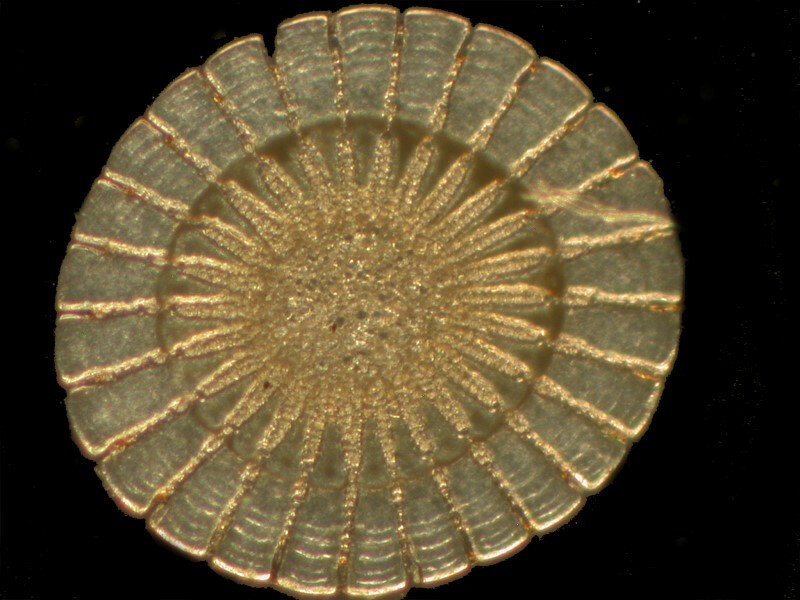

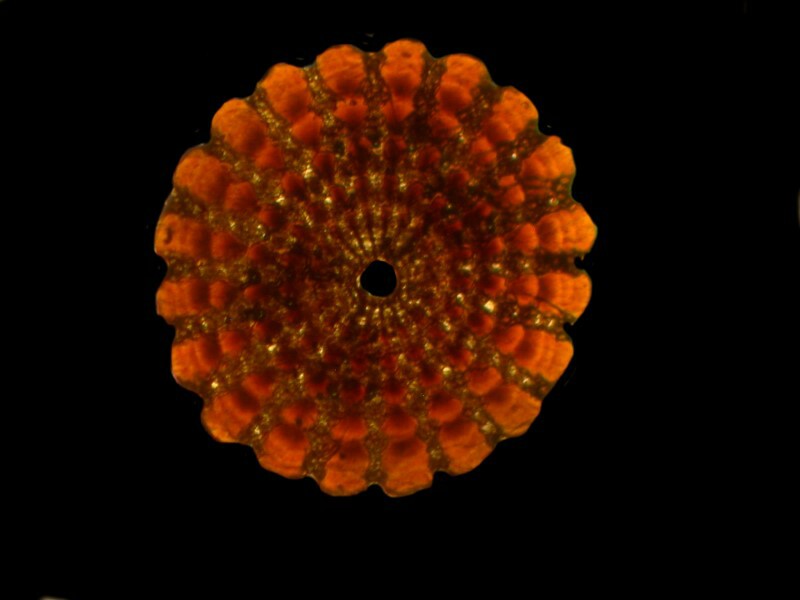

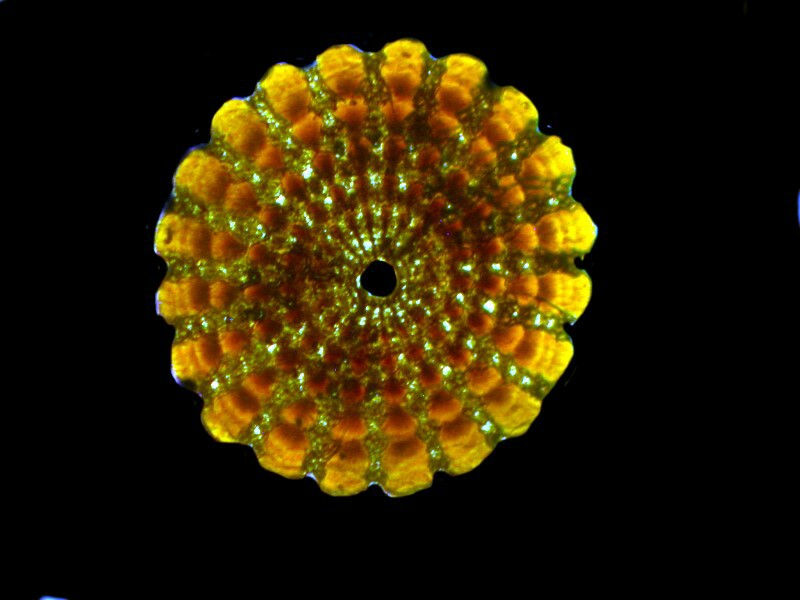

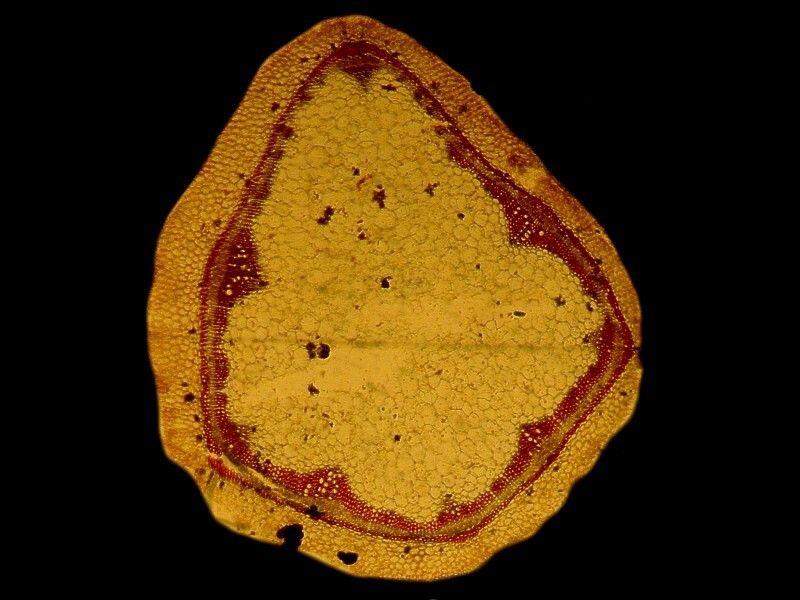

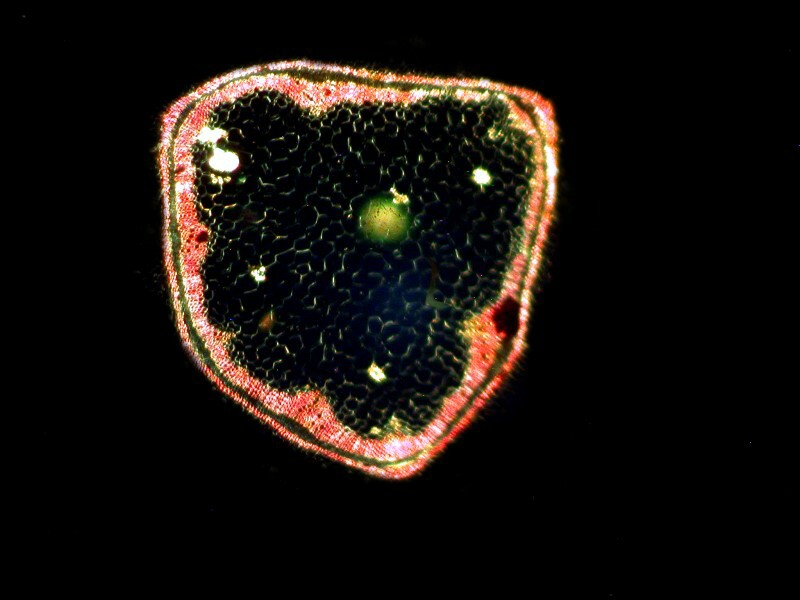

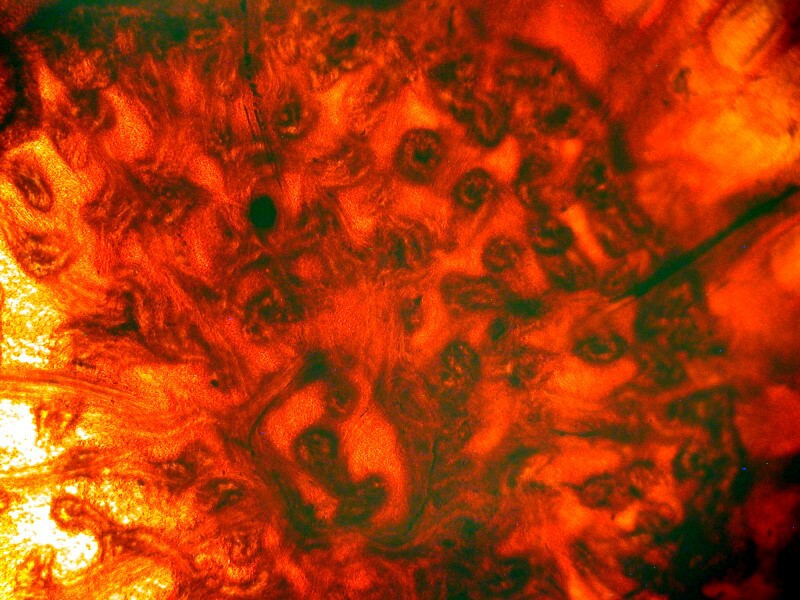

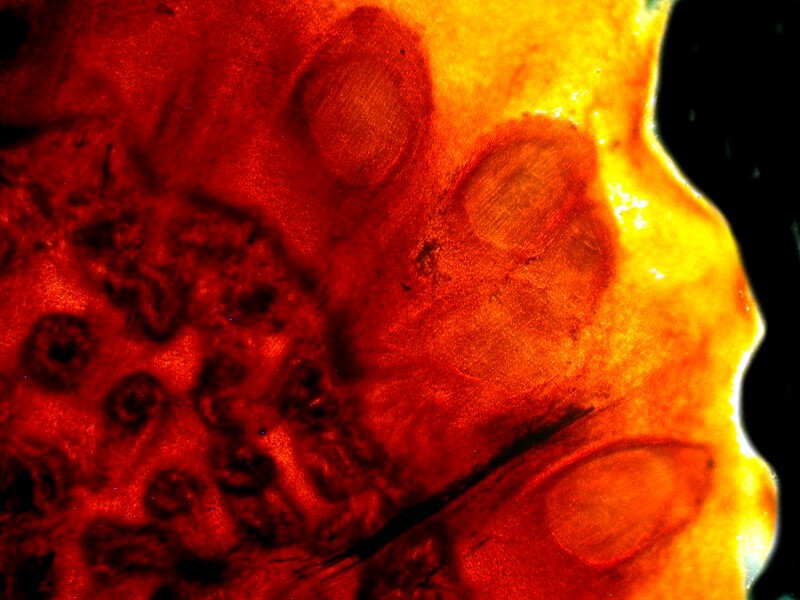

7) A cross section of a sea urchin spine. In many instances, old slides of this type were labeled as cross sections of a spine of the genus Echinus but, in fact, it was often the case that the mounter didn’t know the genus and so ironically Echinus became the generic genus. Nonetheless, this is a nice example.

An image with polarized light:

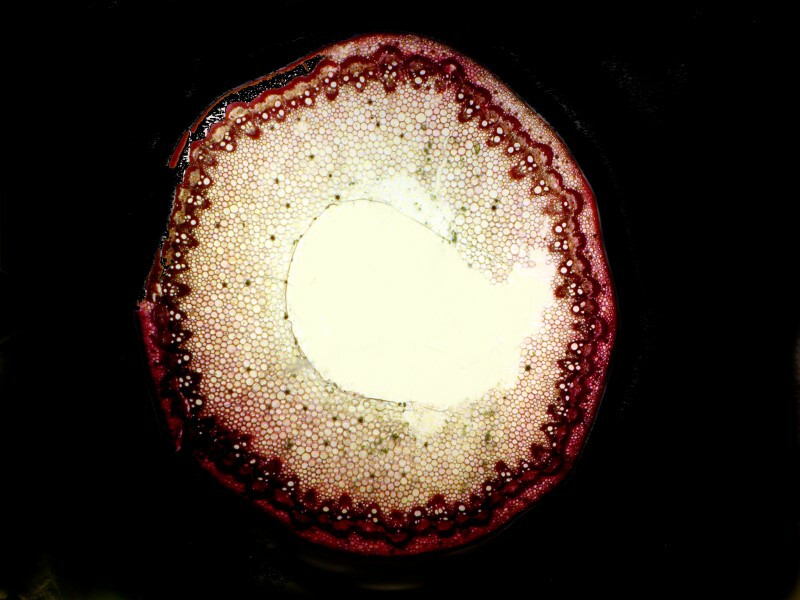

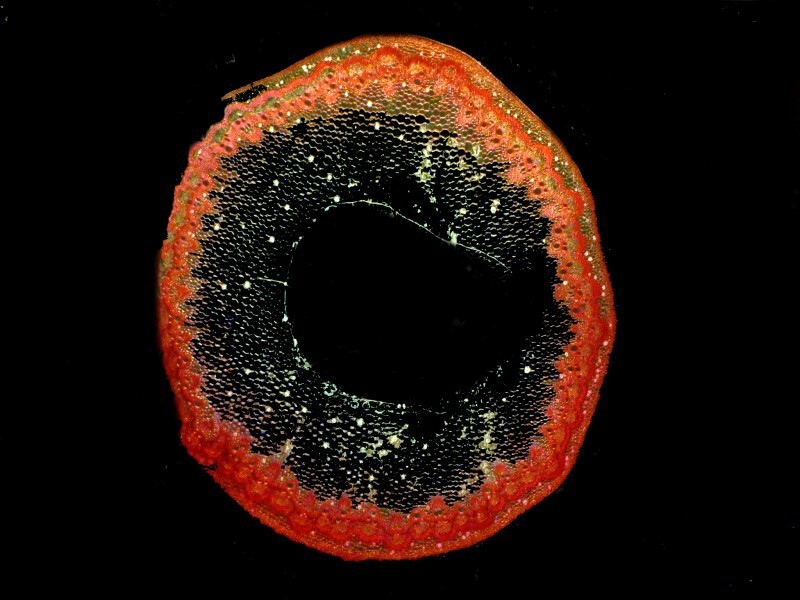

8) Pelargonium (Geranium) transverse section of a stem.

Sections of stems when properly prepared and stained are miniature wonders and have long been favorites of mine. When done with care, they are not only aesthetically pleasing, but provide a great deal of information. These are modestly interesting and not very well prepared. The first image is brightfield and the second is with polarized light.

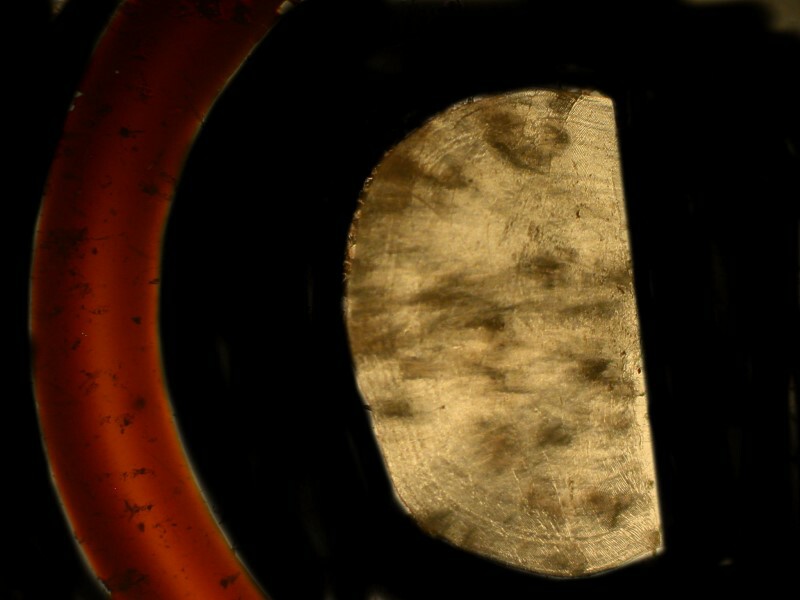

9) Fish scales

There are 3 basic types of fish scales and some marvelously eccentric variants. The three basic types are cycloid, ctenoid, and ganoid. Sharks and rays have placoid scales. This scale fragment is from a cycloid scale since the margins are smooth; if it were ctenoid, then the margins would have spiny projections.

From a different collection of slides, I took an image of ctenoid scales of a sole.

Some are birefringent and some aren’t and with those that are a compensator plate can often be used to advantage. Many fish scales show growth rings analogous to the annular rings of trees.

However, not all scales are created equal. There are calcareous ones which look like a bit of coral. They are embedded under the surface of the skin on the dorsal side and come from a Batfish.

This odd creature has modified appendages which allow it to “walk” along the bottom of the sea bed.

A highly bizarre type of scale can be found on a large fish from the Amazon. These are sometimes sold in curio shops as fingernail files.

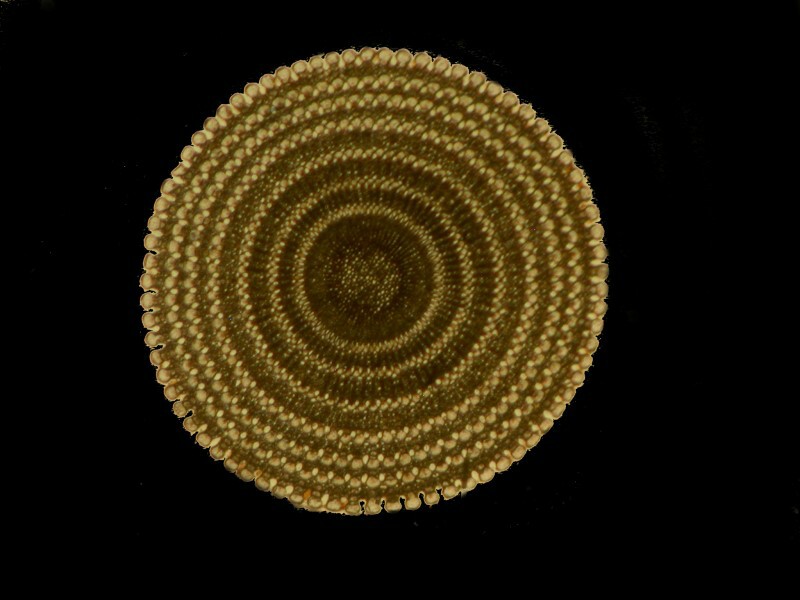

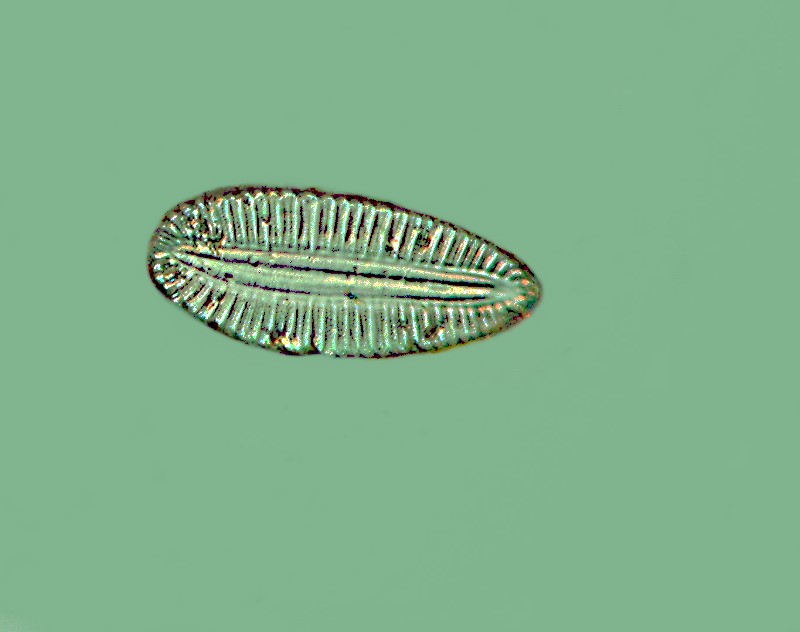

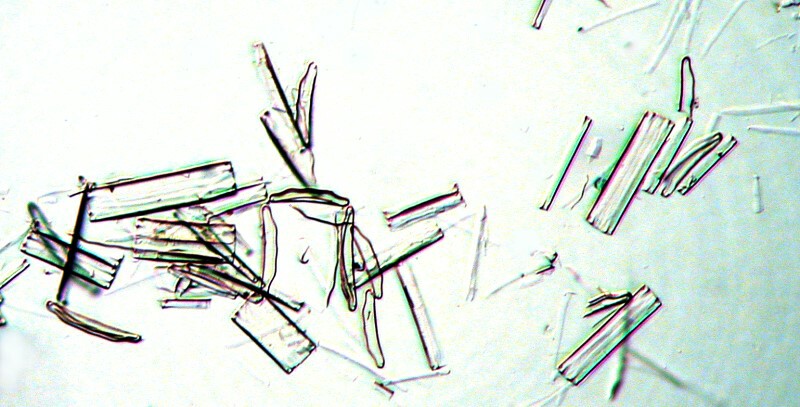

10) Two diatoms

Every microscopist’s collection should include some diatom slides. If you don’t want to buy them, you can make your own with a bit of practice, patience, and care. These are from the genus Surirella.

These were photographed using Nomarski DIC.

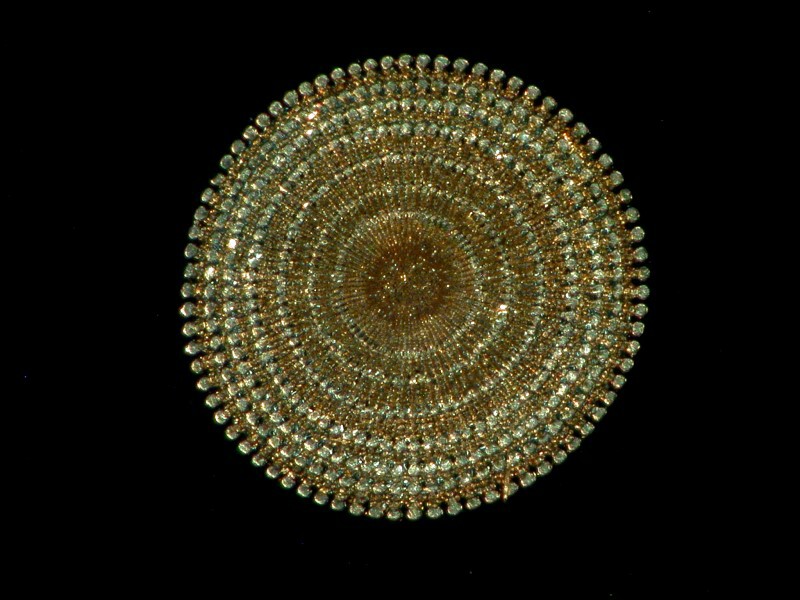

Diatoms, because of their delicate detail, have always attracted microscopists and many went to enormous effort to make arrangements of them. Here is a slide which compared with some is quite modest, yet strikingly beautiful.

11) Peristome of Funaria.

Funaria is a genus containing about 200 species of moss. These are commonly known as “cord mosses”. The peristome is a cap-like structure of the sporangium which allows gradual dispersal of spores.

12) Cross section of ?

If you have any clues, please let me know. It certainly has lots of ridges which suggests that it is organic.

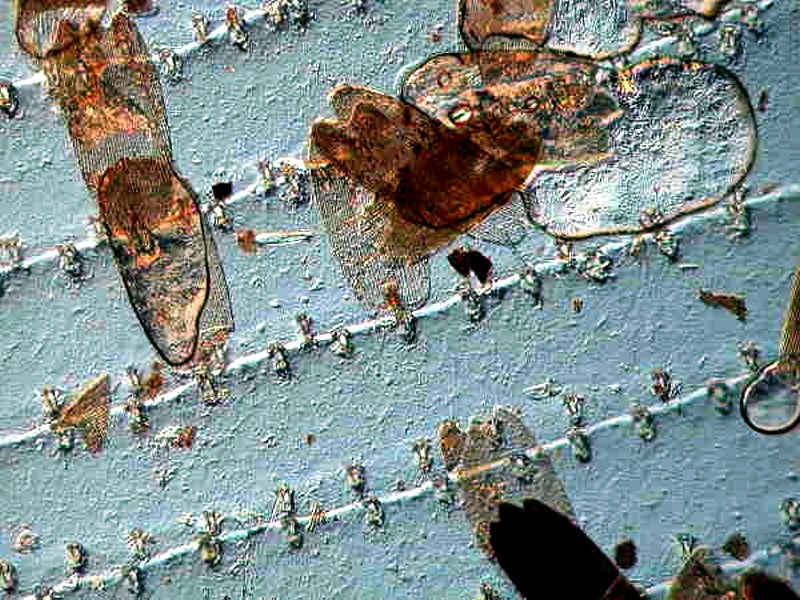

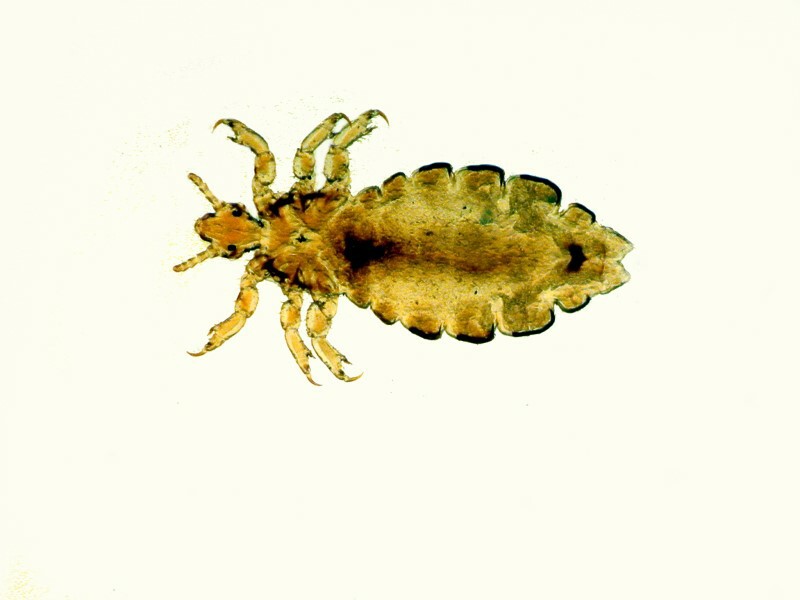

13) Four lice.

These are neither pleasant creatures nor attractive ones, but they are another illustration of the incredible adaptability of life forms. Who would image that such creatures could find sustenance living on the human scalp?

14) Transverse section of a Clematis stem

A pleasant, but undistinguished botanical preparation. (Doesn’t that sound pompous and professorial?)

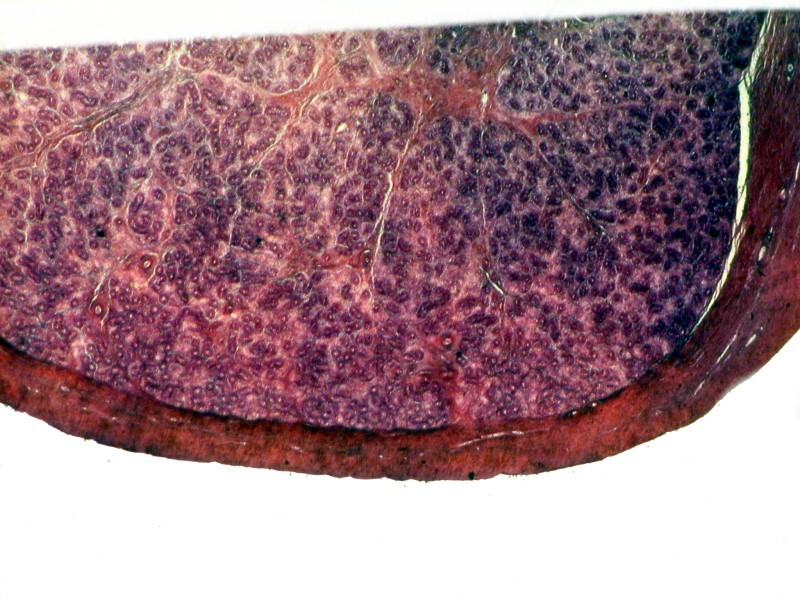

15) Section of testicle.

I am reminded of the story of a young coed who was complaining about her professor’s difficult little quizzes. The girl she was talking to replied: “You think those are difficult; wait until you see one of his little testes.”

There is no information as to whether this comes from a pig, a bull, or a human. Nonetheless, the very idea makes many males a bit queasy when they are discussing diatoms over a meal of Rocky Mountain “Oysters”.

16) Polygonium. Transverse section of stem.

This is an interesting section because one can see some crystals in the tissue. Here is a brightfield image.

And here is an image using polarization to see if the crystals are birefringent.

17) Urtica dioica. Transverse section of a stem.

This is the common or stinging nettle. It has been used to treat allergies but, of course, it can be very unpleasant if you unwittingly encounter it.

This botanical preparation is of interest, for one reason among others, because it shows a tiny hair attached to the stem. We often tend to forget just how hairy plants can be and in this case it is the hairs that inject toxins into the skin of the unwary.

18) Cobaea scandens pollen. Popularly known as the cup-and-saucer vine, cathedral bells, Mexican ivy, monastery bells.

19) Himantidium. This is a diatom strew slide.

If you find or buy some really nice diatom material and want to make a strew slide, the cardinal rule is not to put too much on any single slide. Getting the right sort of density requires a bit of practice since you don’t want to have only 10 diatoms scattered over a 22mm by 22mm area, but even worse is the situation when the diatoms are in clumps and pile up obscuring one another.

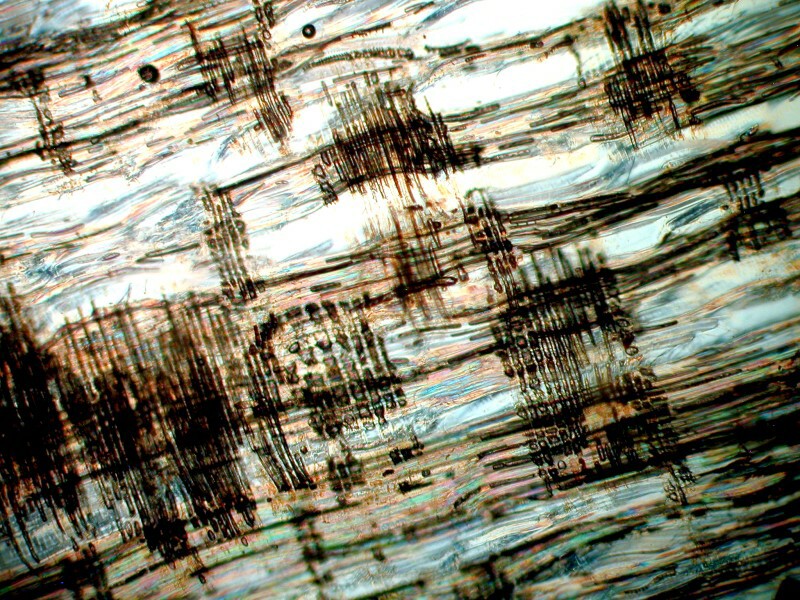

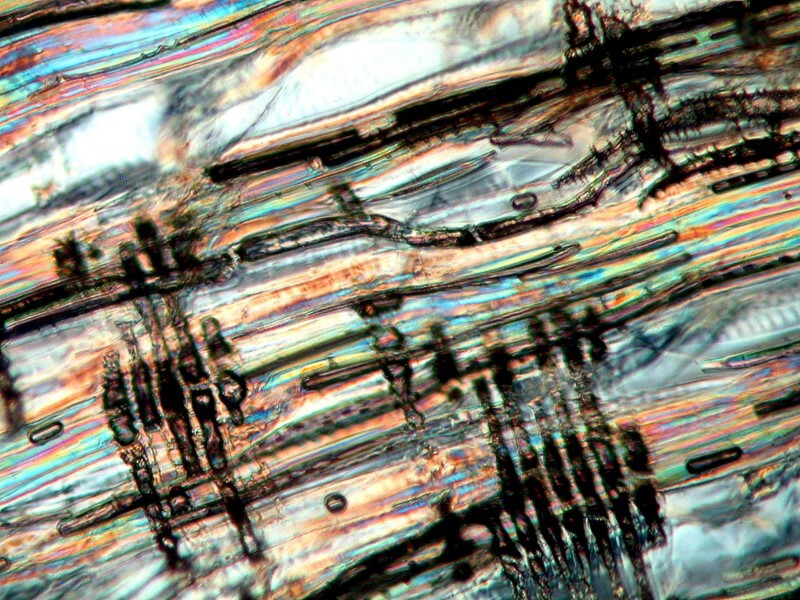

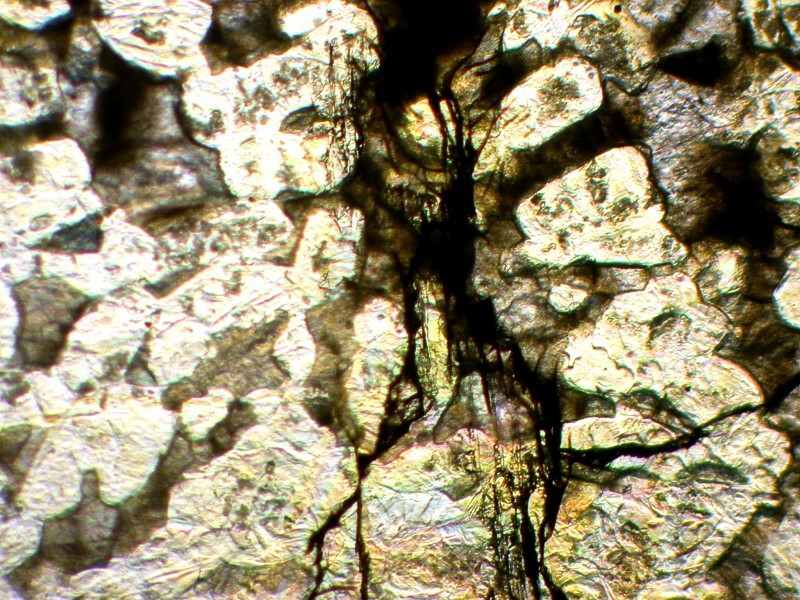

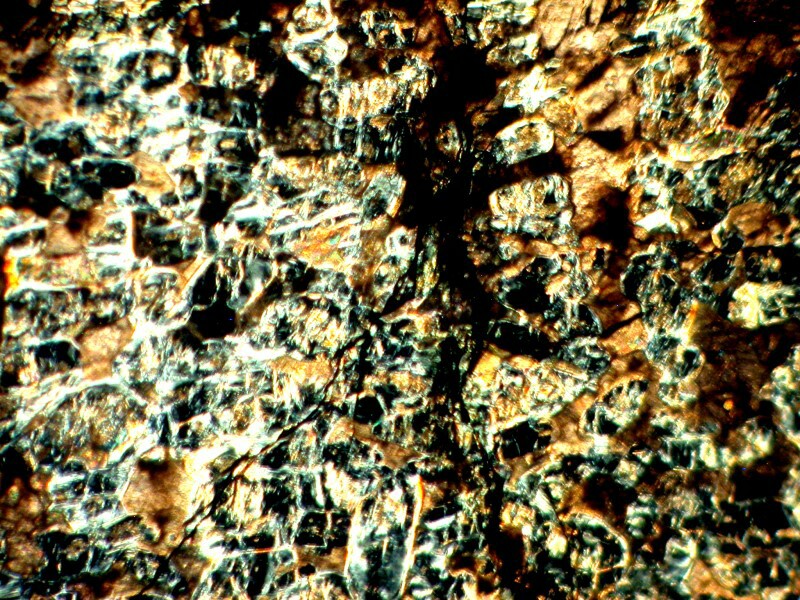

20) Cross section of wood?

Could be, but frankly, I don’t know. First, a Nomarski DIC image, then a polarized image.

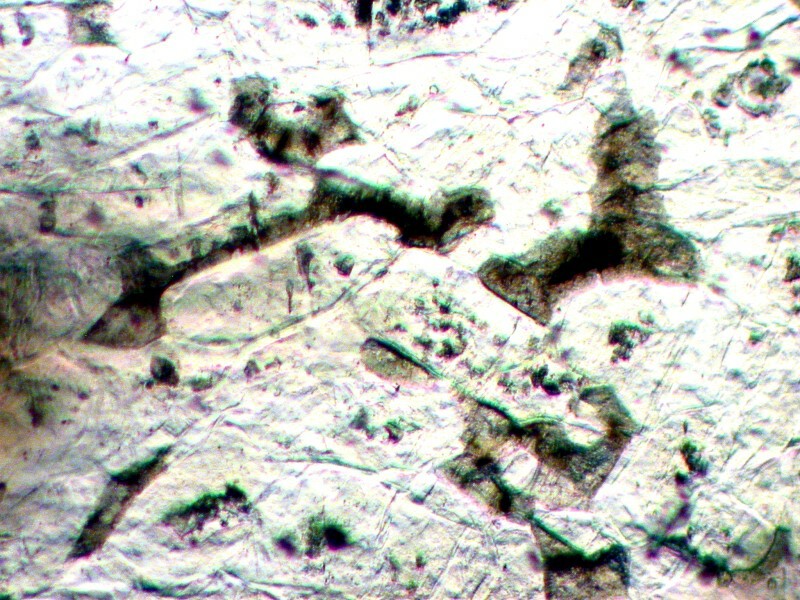

21) Eozoon canadese (Petrology) (Transmitted light or Polariscope)

Unfortunately, this slide arrived broken and is just hanging together (with masking tape, of course).

I was immediately curious about the fact that it is labeled as being a Petrology slide, but the description “Eozoon” suggests that the specimen is of animal origin. It was first thought to be a large foram and later discovered to be a crystalline mixture of calcite and serpentine. It is unclear whether there are any remnants of a specimen here; I’ll let you decide.

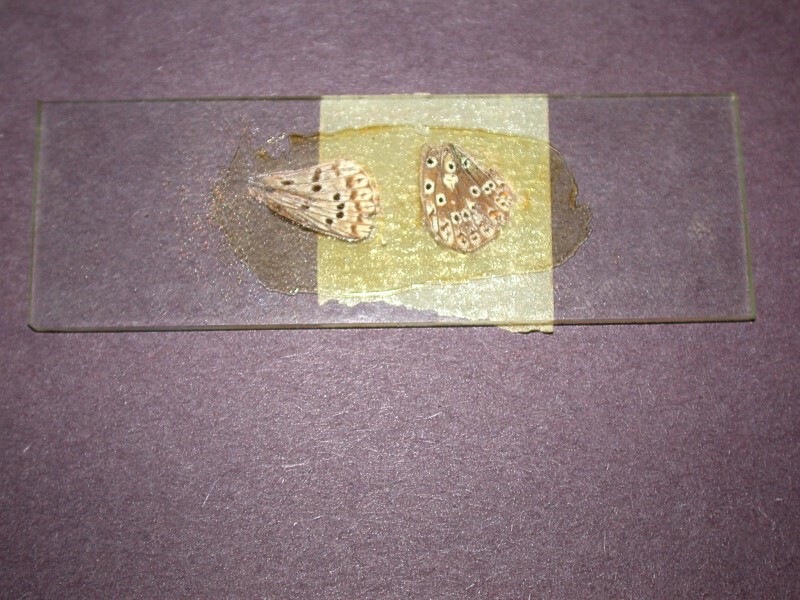

22, 23, 24) Butterfly wings

To paraphrase Gertrude Stein: “A wing is a wing is a wing is a wing. The world began with a wing.” Well, we all know that that’s not so, neither with roses or wings. However, if you think so, I have some splendid pterodactyl wings I’ll be happy to sell you.

Butterfly wings are always of interest if they are mounted in such a way that they allow one to investigate and determine their structure. These are almost decent, but not exciting preparations. One major drawback is that no cover glasses were used, but rather merely a layer of mountant painted over the specimens.

25) ?–Again, I haven’t a clue. Perhaps you can make some suggestions. If forced to guess, I suspect it may be a section of some plant tissue.

26) This last slide is not standard size, but somewhat larger than usual and the specimen justifies this. It is a hellagrammite or larval form of the dobson fly.

And when “cleaned up” with the help of the graphics program, we get a result that looks like a wall painting from an ancient pyramid.

These are fierce predators and if you collect some in your pond samples to take back live to your lab, be sure to keep them in separate containers away from other larvae you might wish to study and away from each other–they are cannibalistic! Here is a look at the jaws.

And, finally, here is a closeup.

The price of the collection was worth it for this single slide, but along with it came a number of very nice bonuses such as the section of the Echinus spine, the radiolarian strew, and the pollen of the Evening Primrose. A very nice surprise for a very modest cost. Would that I could find more such bargains but, these days even in a severe recession, there are, for my taste, too many aggressive collectors who are willing to spend too much money. Of course, I say this every time I get outbid.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the March 2016 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .