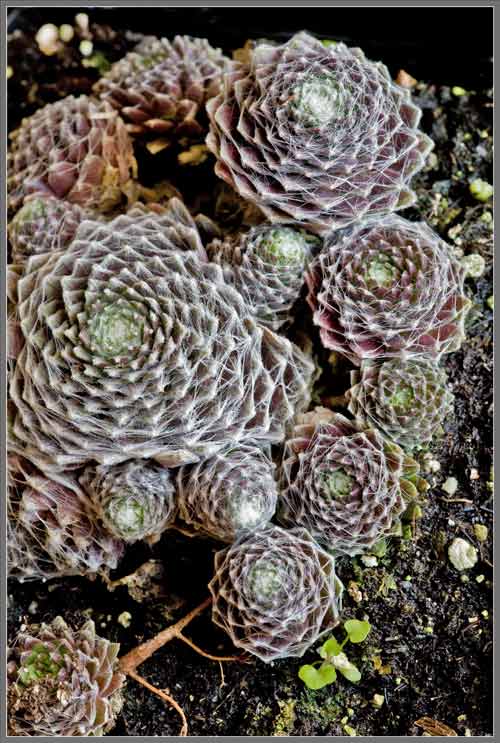

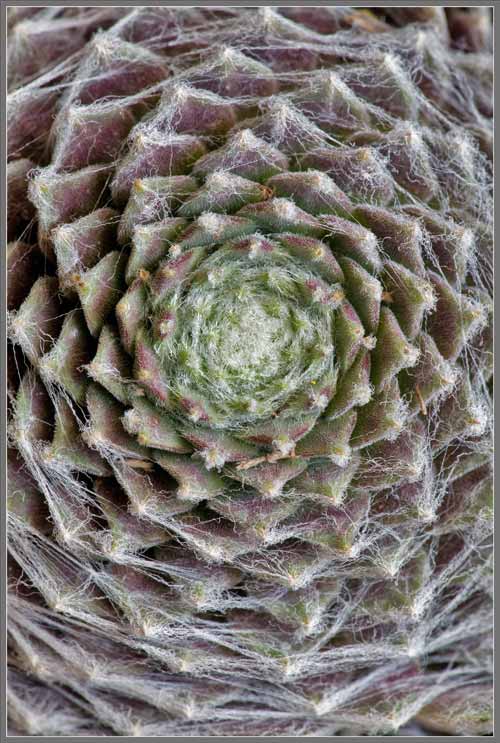

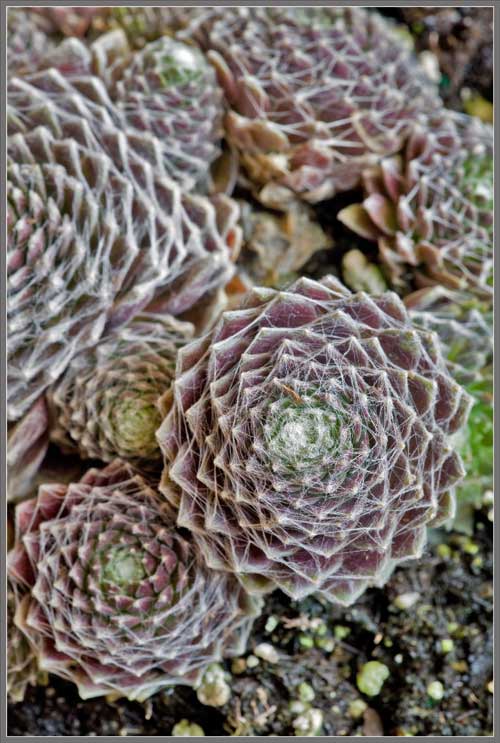

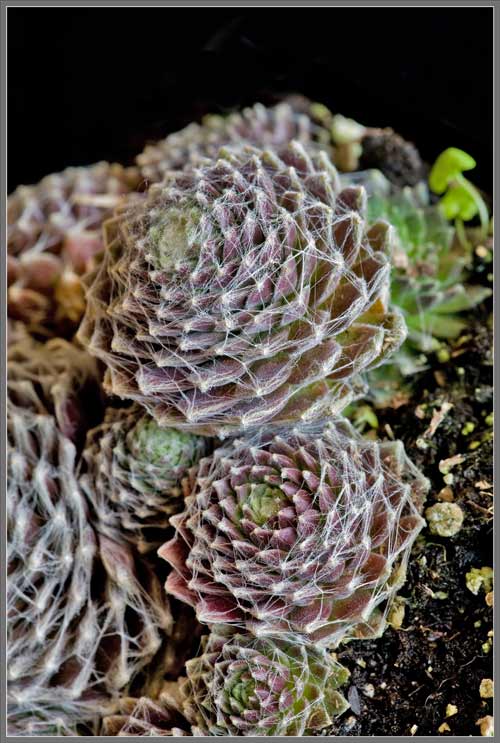

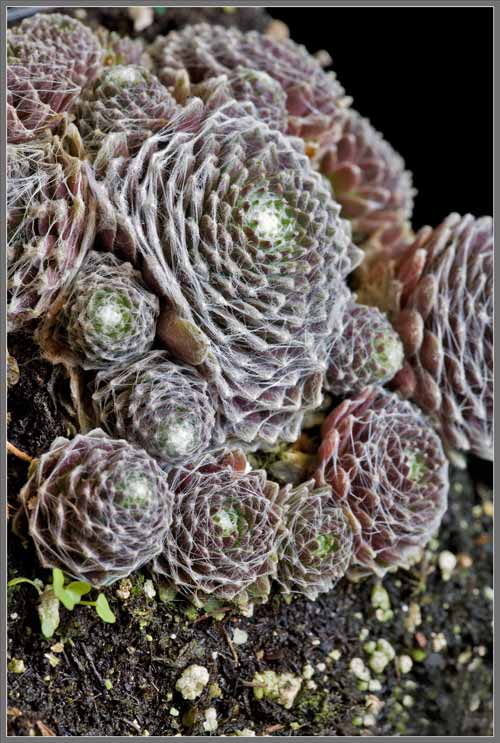

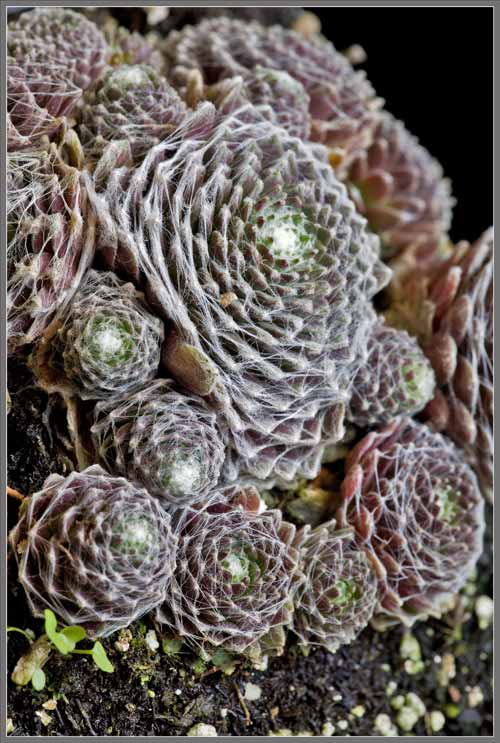

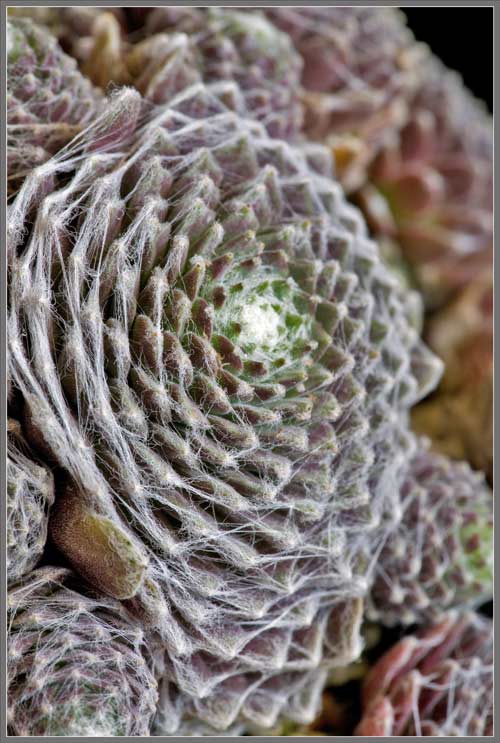

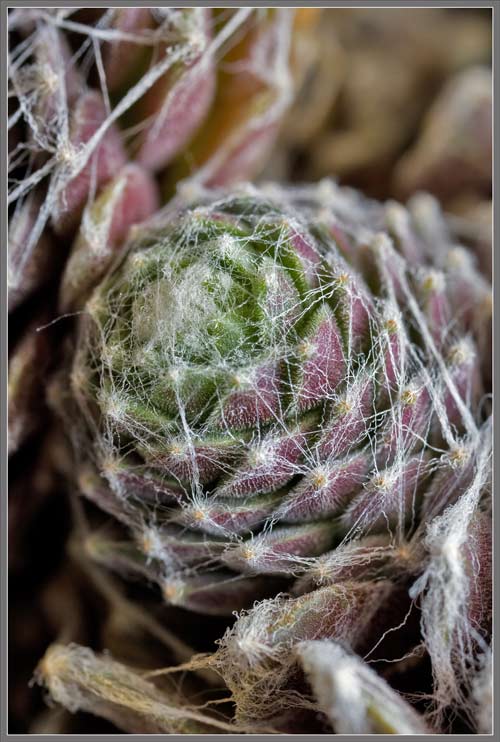

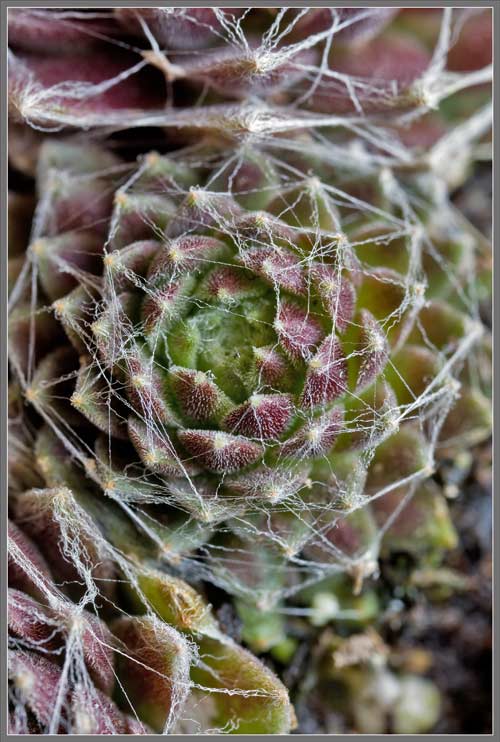

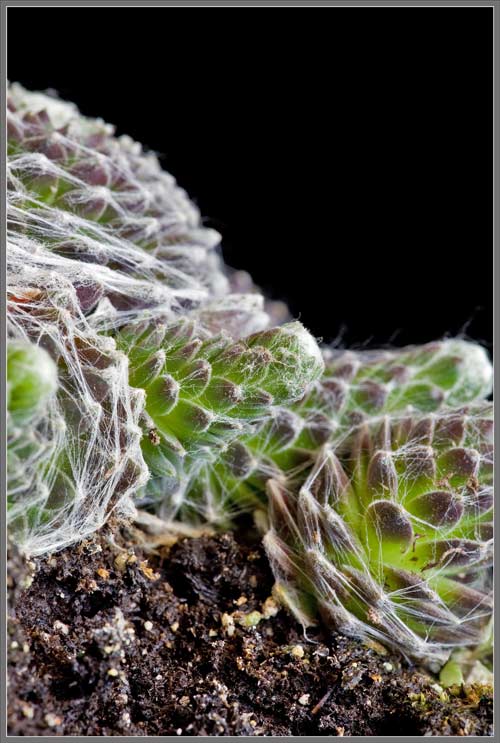

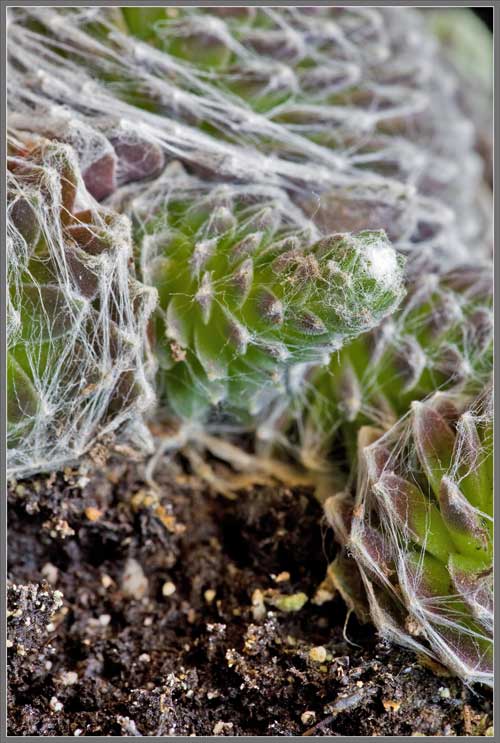

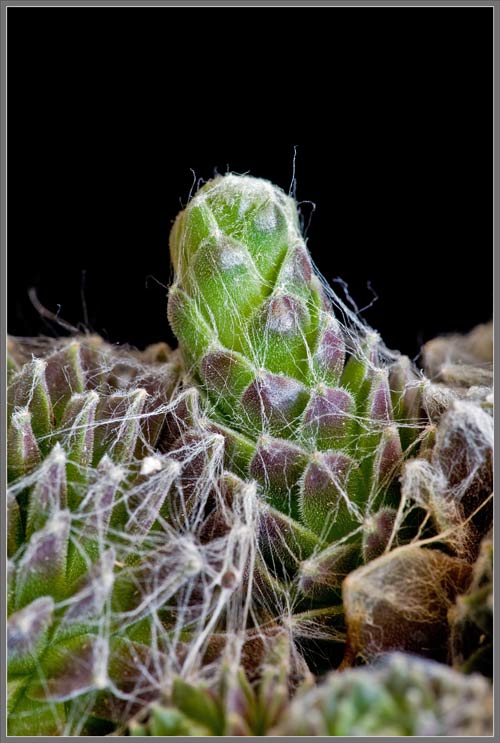

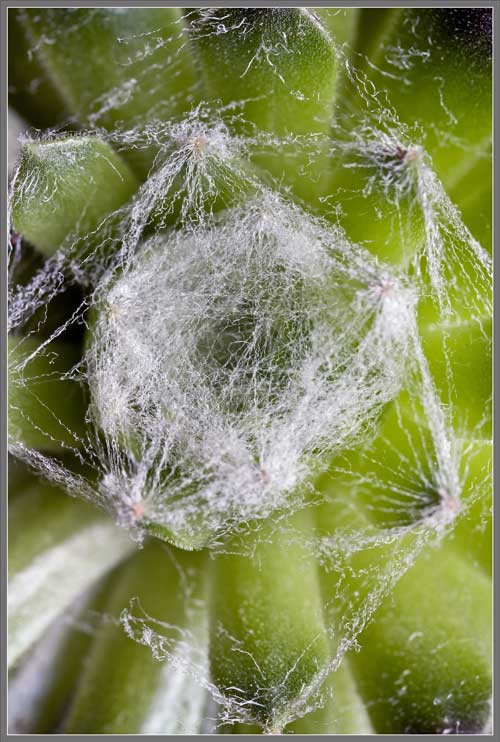

“Of all the Houseleeks

neatest far

The jolly

Cobweb

Houseleeks are.”

Walter Ingwersen 1943

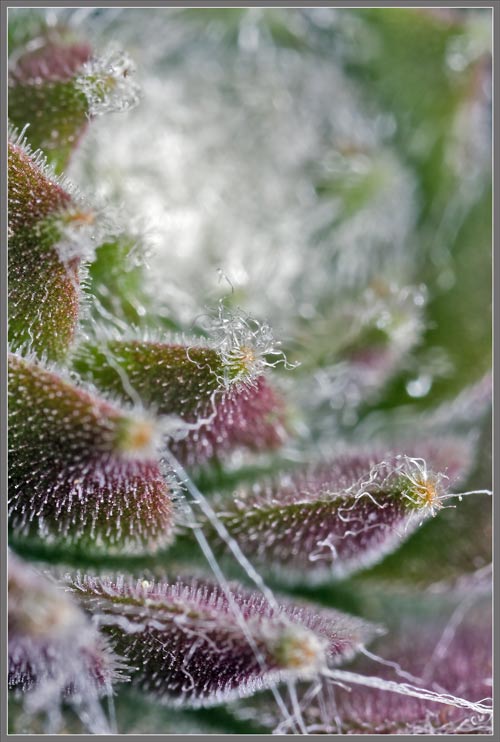

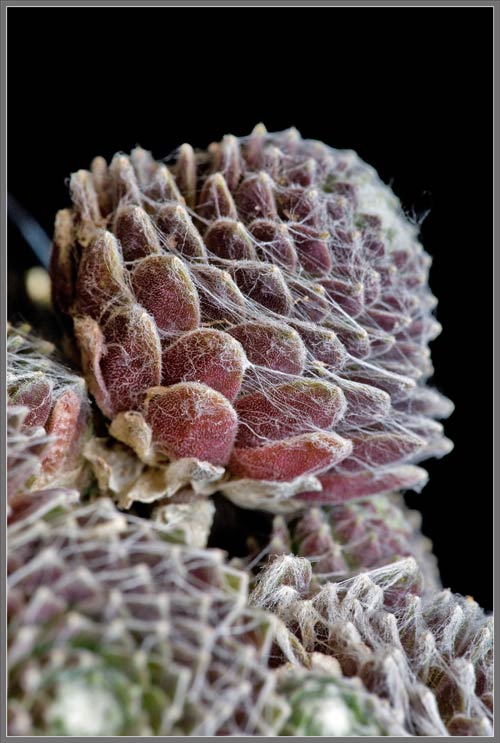

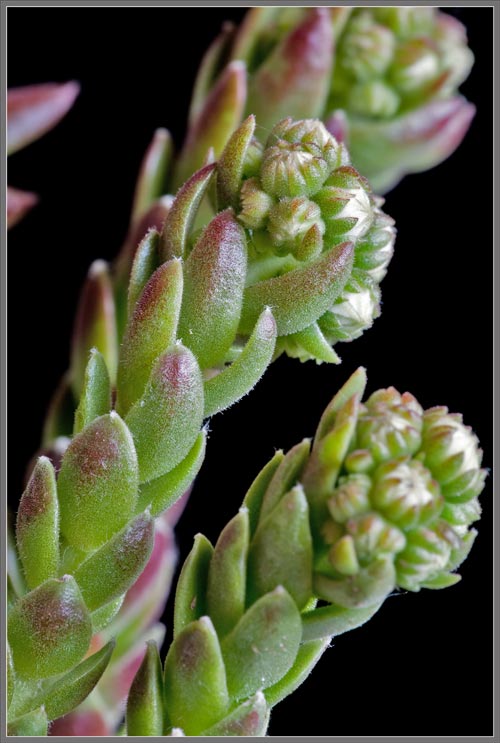

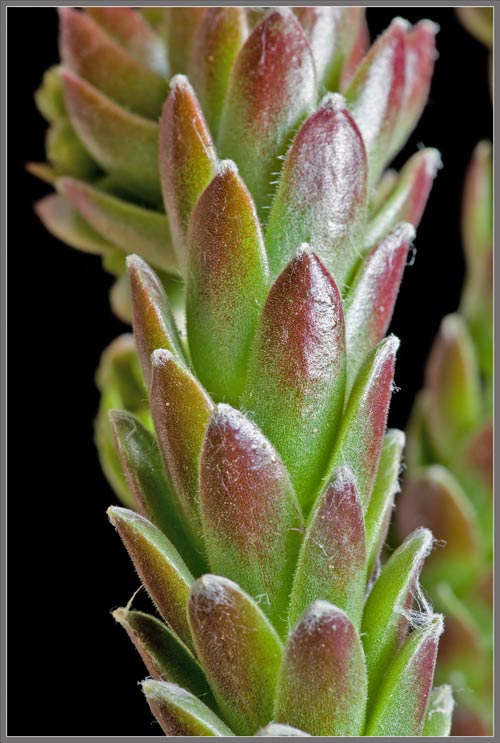

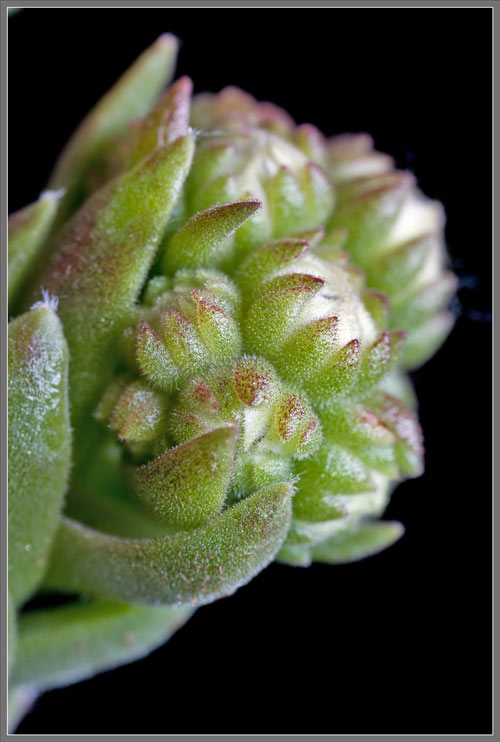

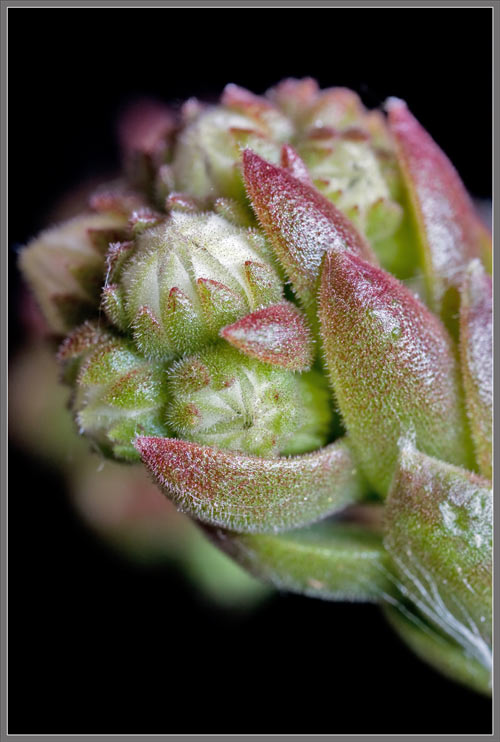

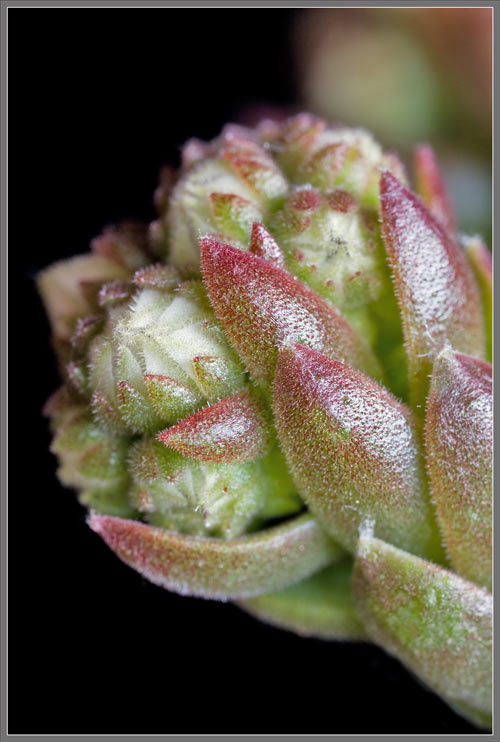

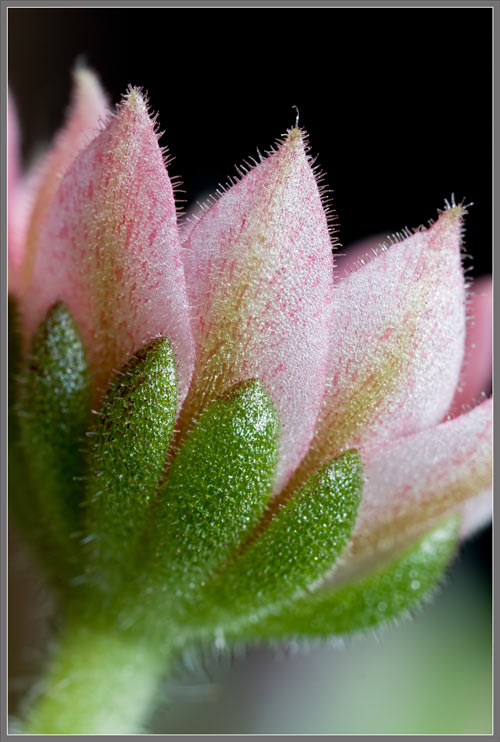

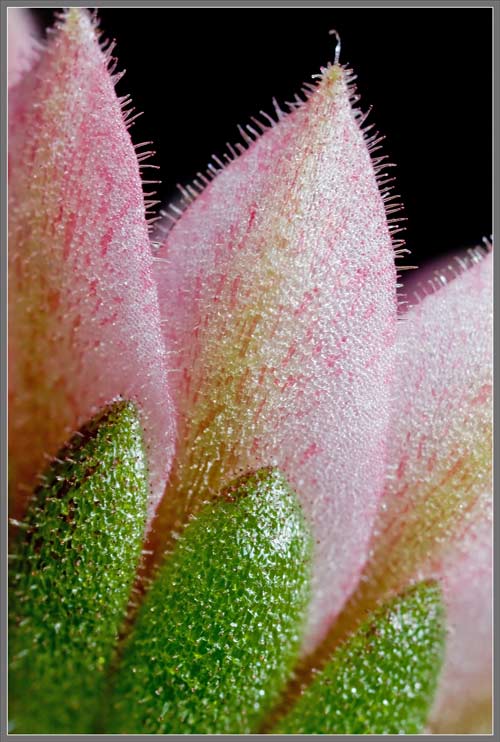

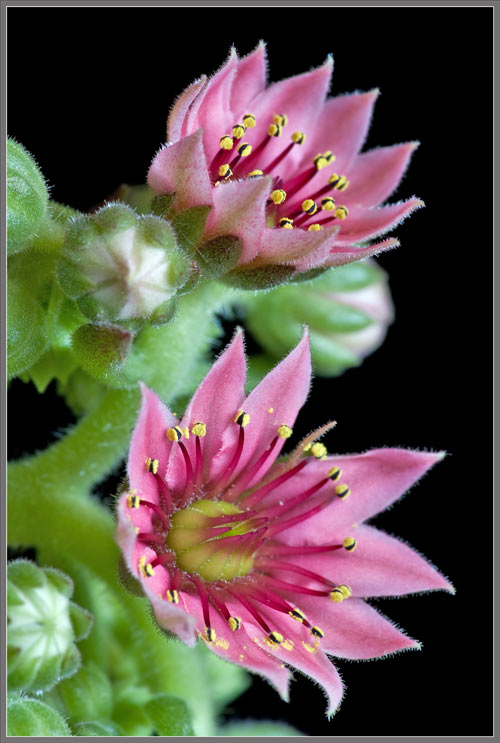

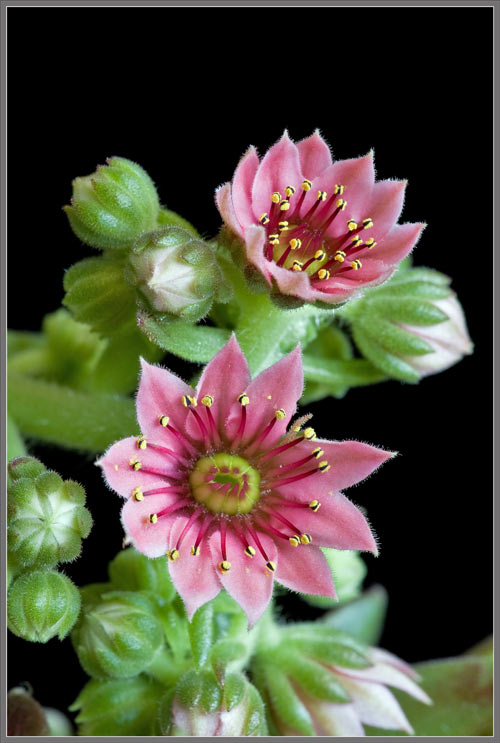

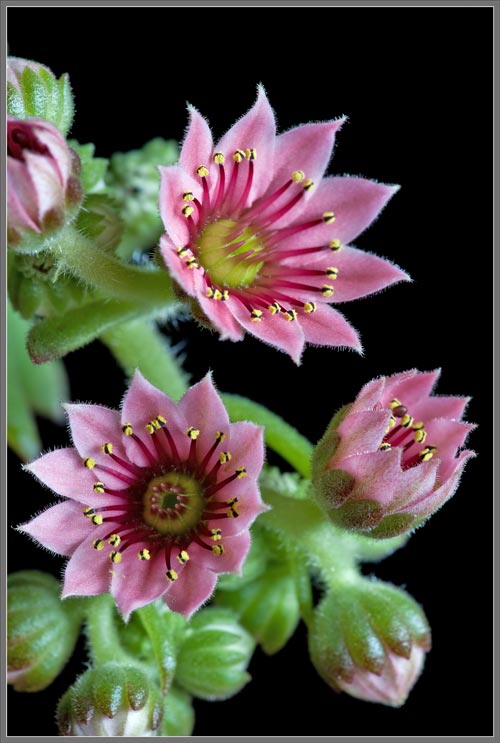

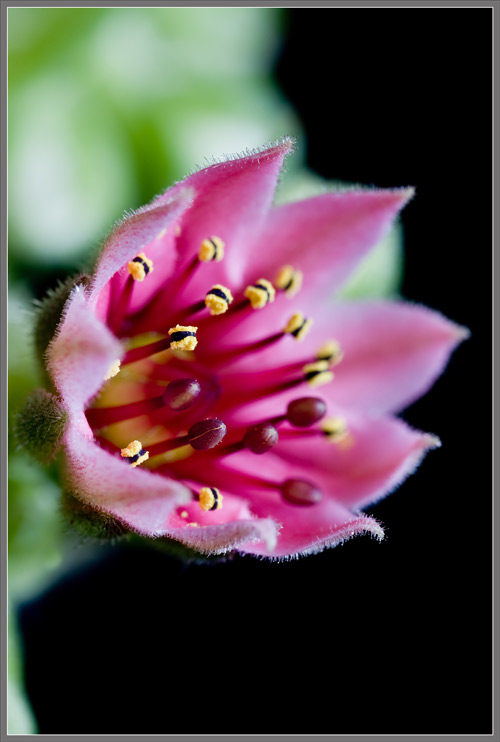

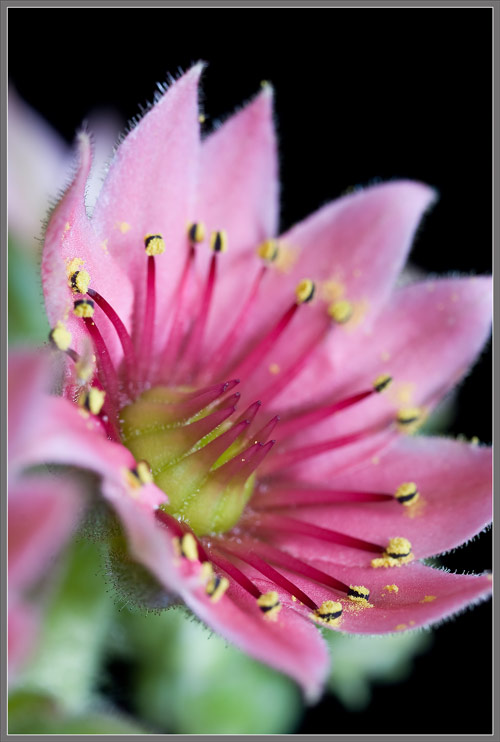

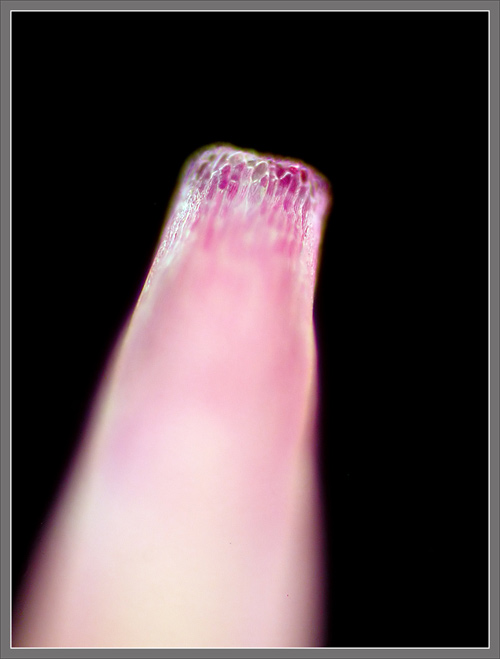

At

the

magnification shown below, it is apparent that both the

sepals, and

the flower’s petals are covered with fine hair-like

projections.

The whorl of pink petals is referred to as the flower’s corolla.

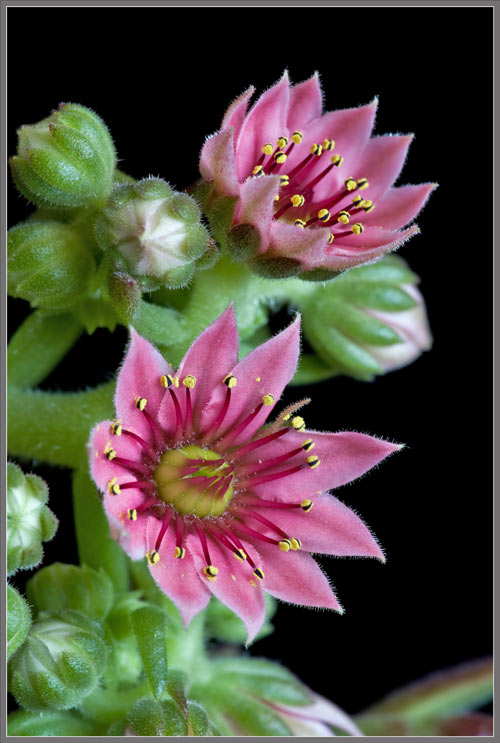

The petals of the flower grow

from

the edge of a yellow dome-shaped disk, and the male stamens grow

from a

ring where the petals meet the disk. Emerging from the

disk

itself is a group of bright red female pistils.

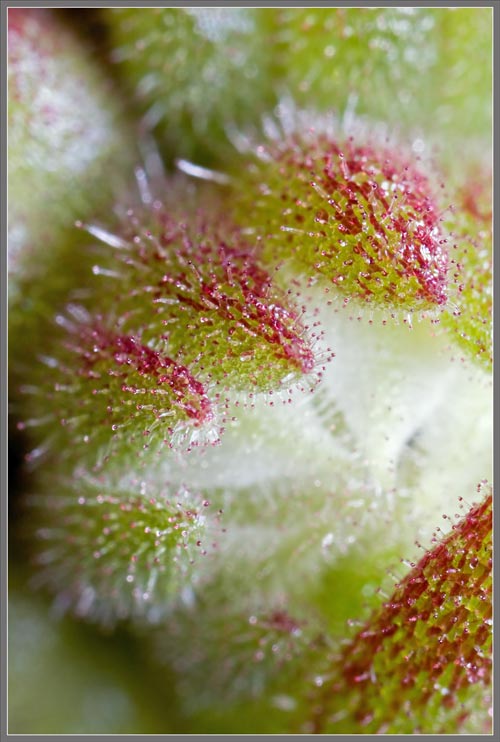

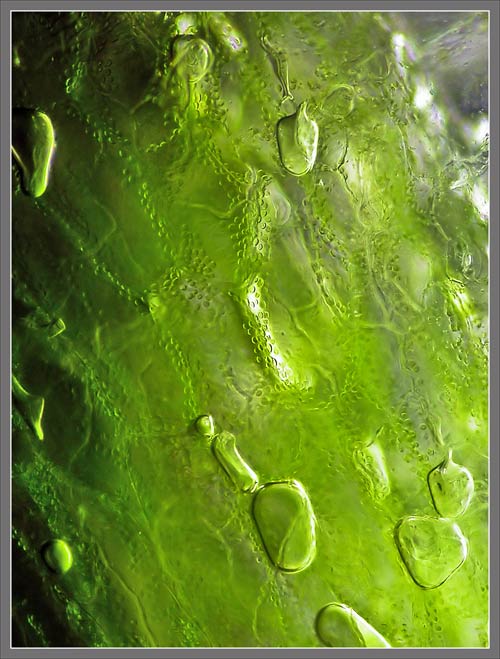

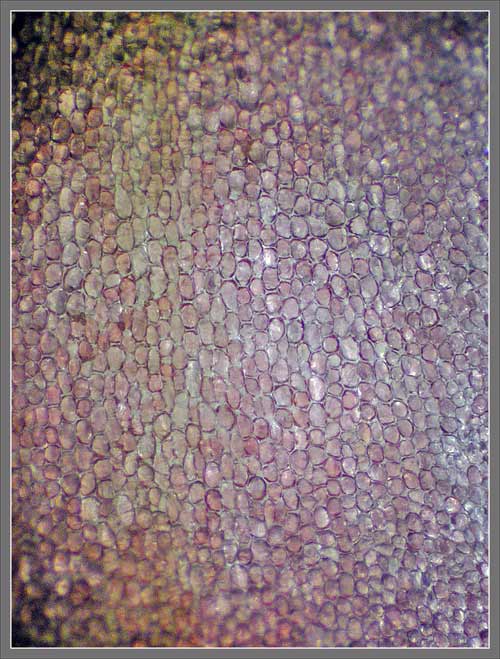

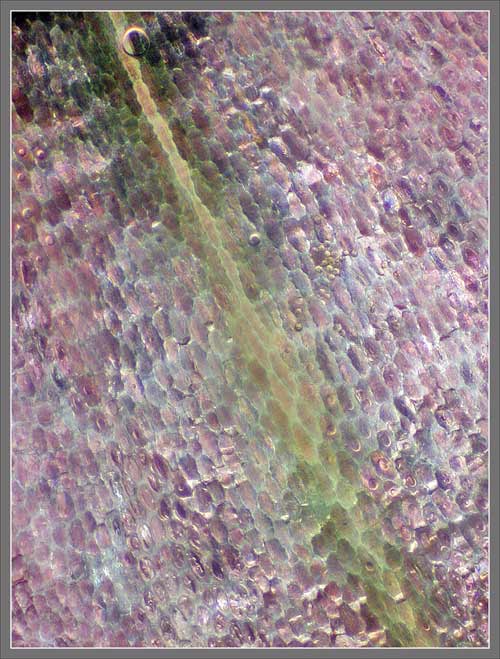

If the surface of a green

sepal is

examined under the microscope, the subtle green colouration is

reminiscent of a pastel painting. Note that a water mount

was

used, and this accounts for the occasional bubble in the field

of view.

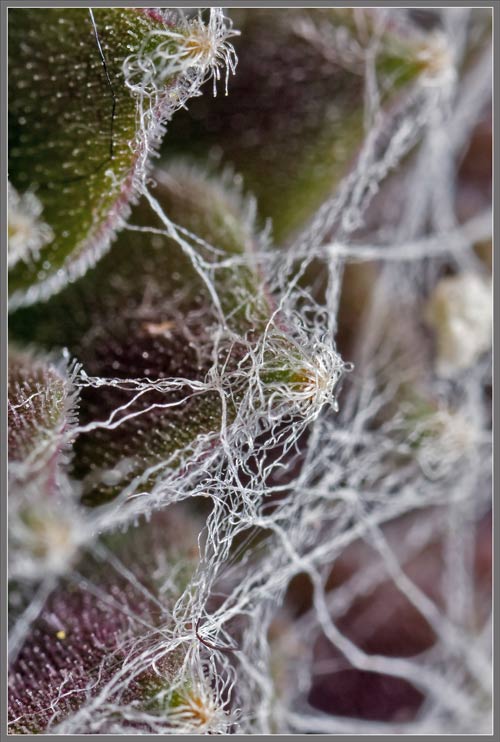

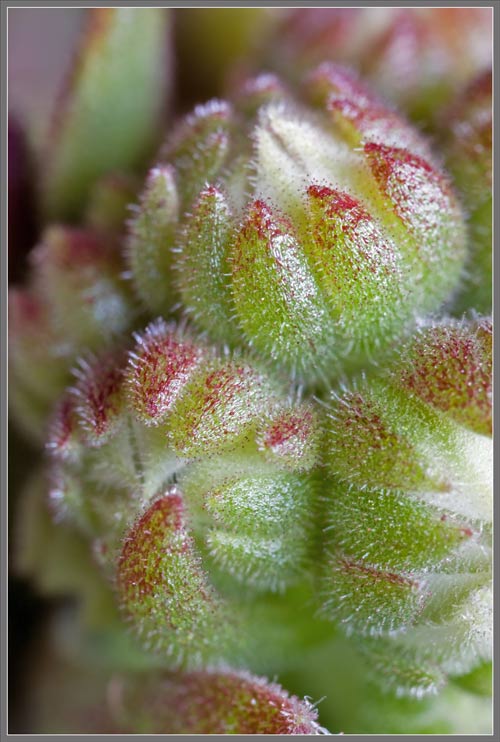

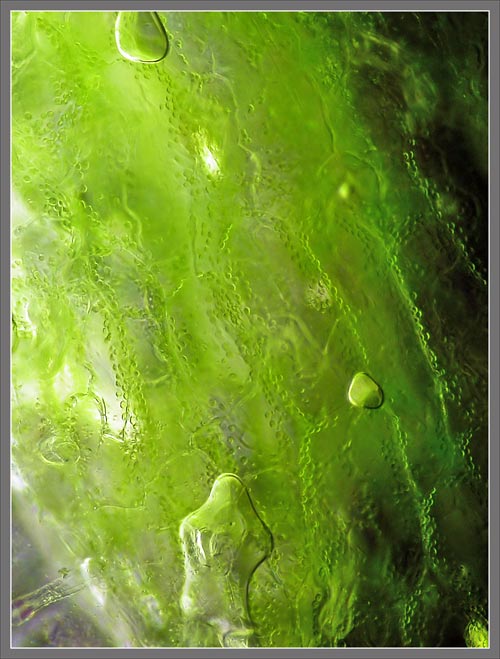

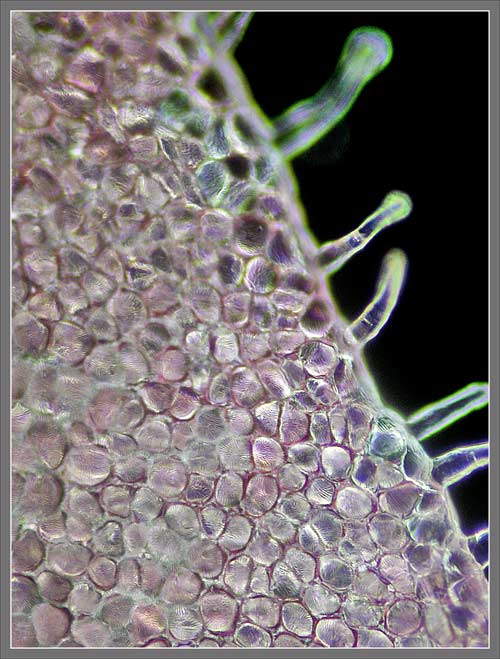

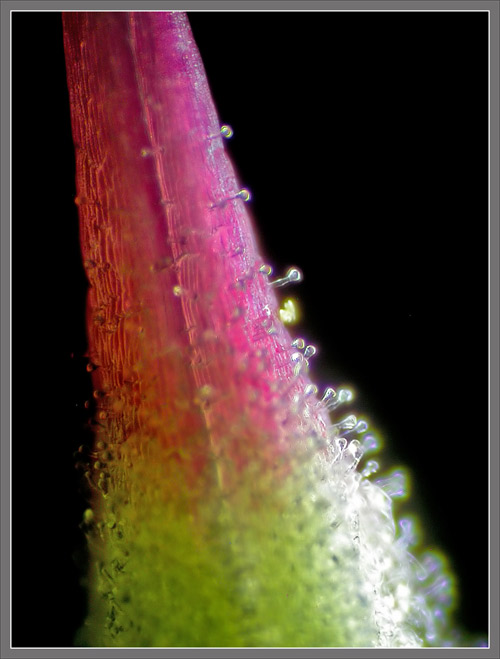

Near the edges of a sepal,

some of

the glandular hairs seen earlier are visible. Notice that

the red

colouration in the glandular, bulbous tips is localized in two

distinct

areas!

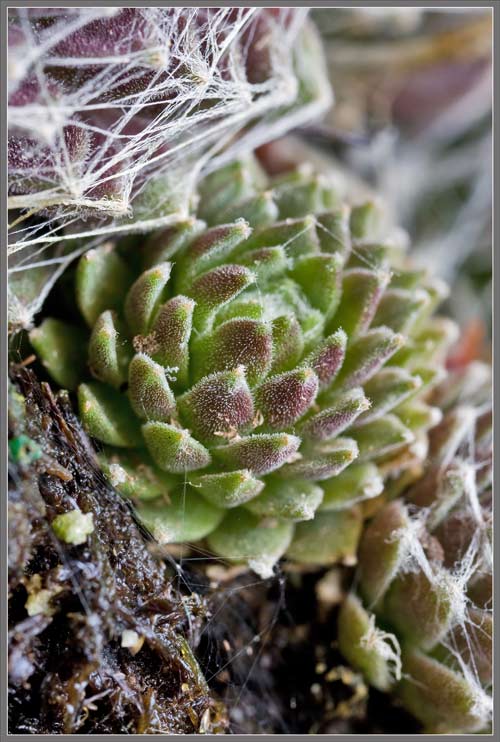

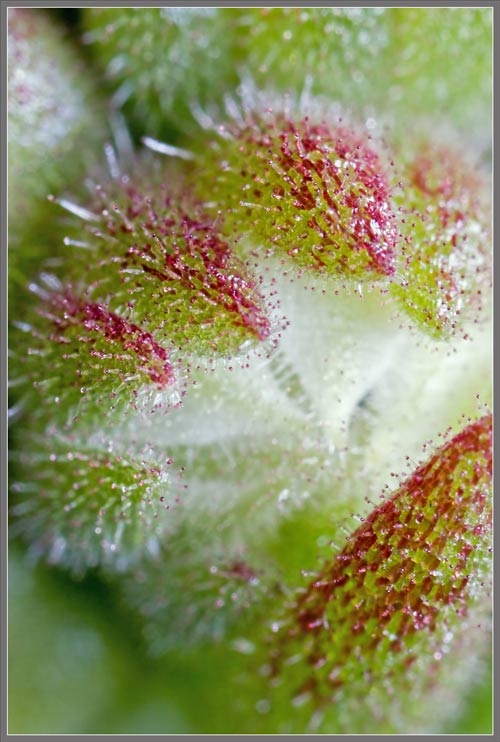

The use of a different

lighting

technique emphasizes the bulbous tips of the hairs, but does so

at a

lower resolution.

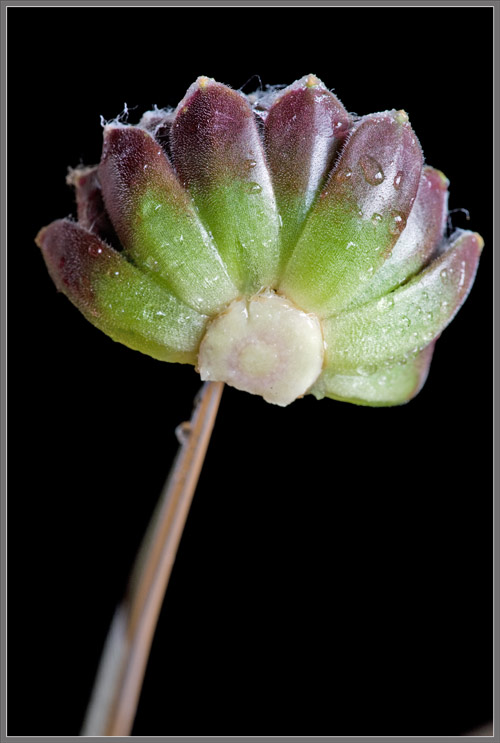

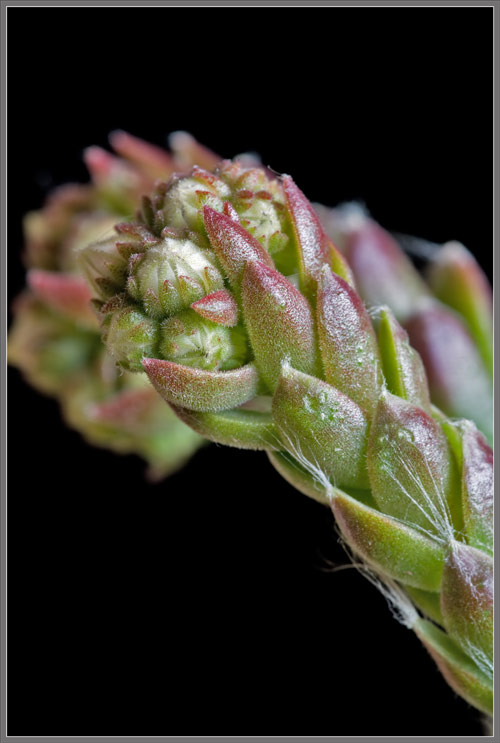

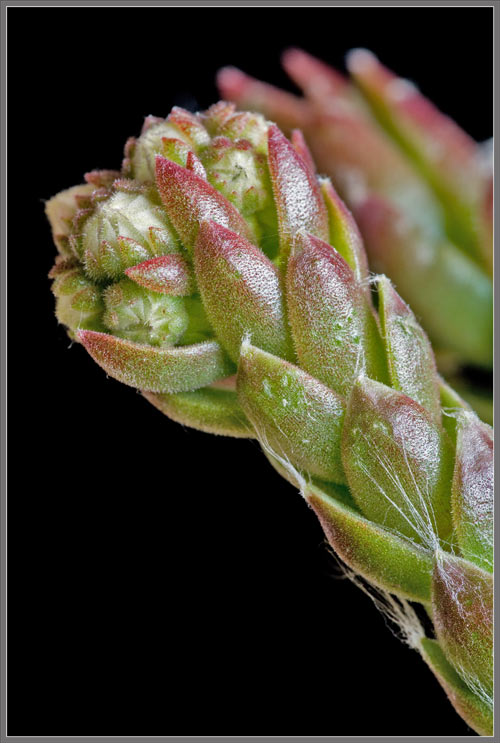

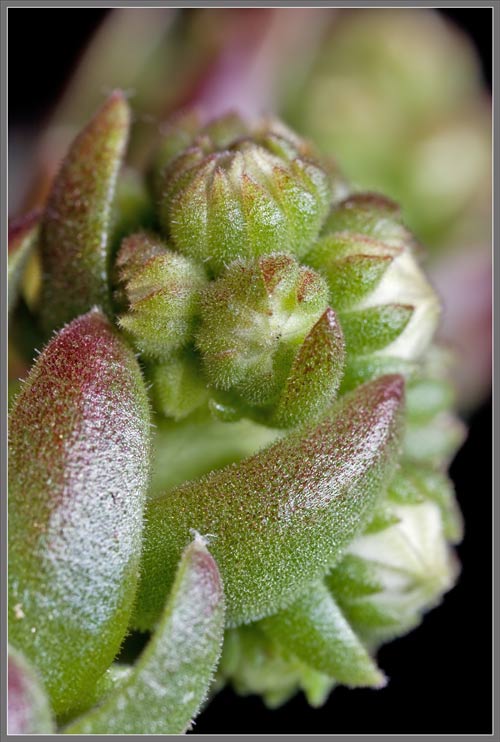

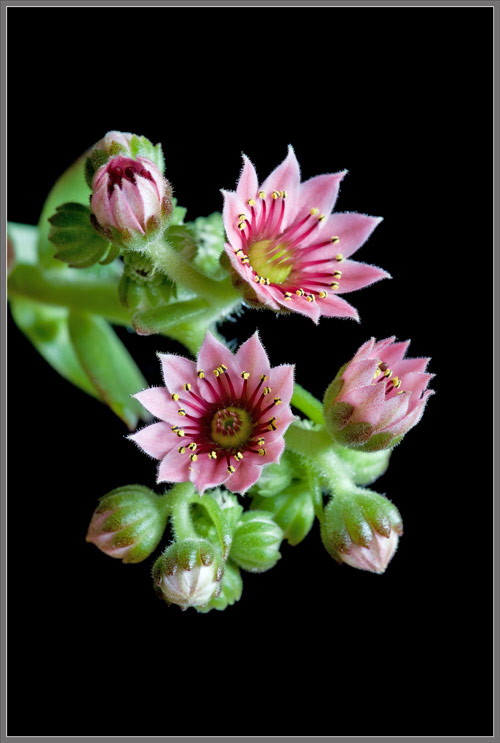

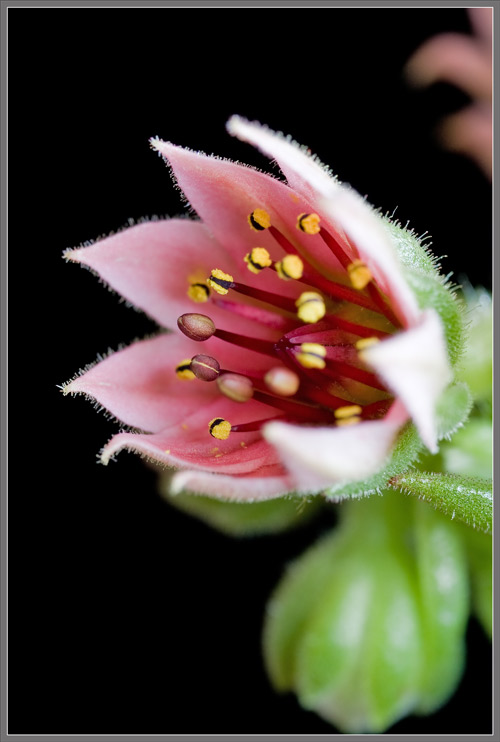

More images of flowers at

different

stages of development follow. Next, we will look at one of

a

flower’s pink petals with the aid of the microscope.

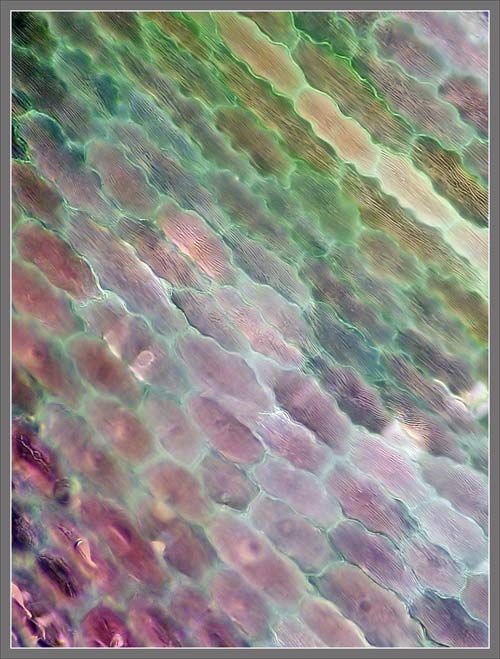

Photomicrographs of the

surface and

edge of a petal can be seen below. Its cells are

irregular, both

in shape, and pink colouration. Hairs growing along the

petal’s

edge are visible in the second image.

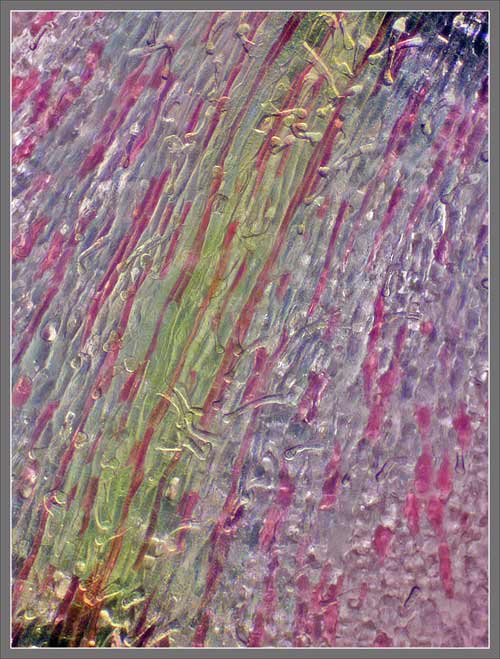

A petal vein can be seen in

the

image on the left below. The image on the right reveals

the

presence of glandular hairs on the petal’s surface.

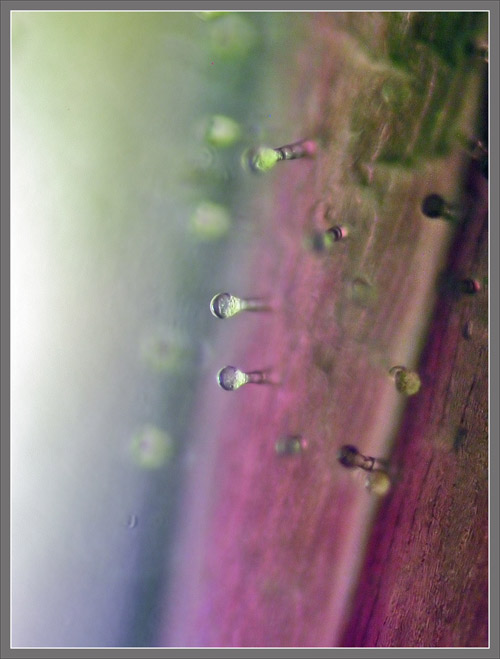

A higher magnification shows

the

longitudinal striations on the surface of individual cells (left

image), and the bulbous tips of glandular hairs (right image).

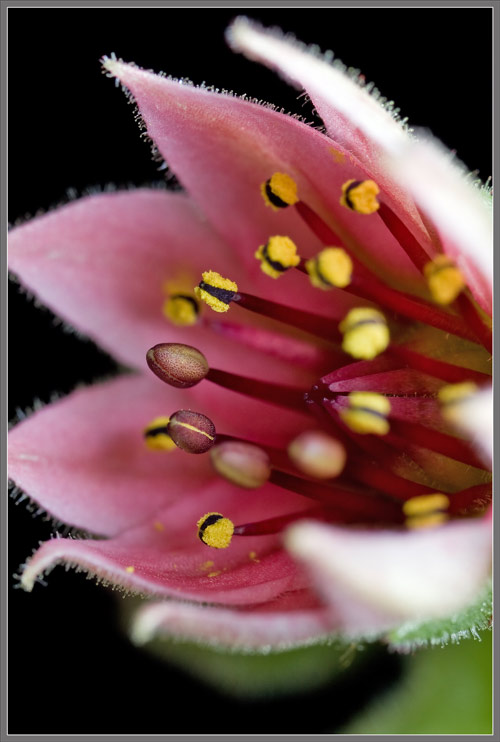

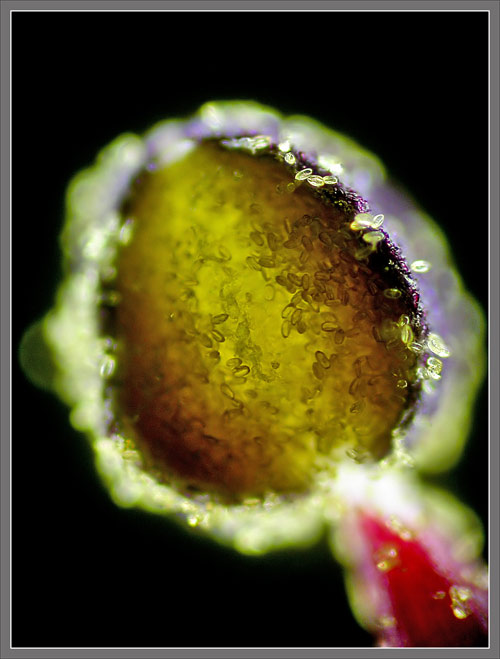

In the sequence of three

images

that follows, some of the anthers are covered by a thin purple

membrane

which hides the developing pollen grains beneath. In more

mature

anthers this protective purple membrane has disintegrated.

Notice the unusual surface

texture

of the anther at the centre of the left image. The image

at right

shows a membrane that has split longitudinally to reveal the

yellow of

underlying pollen grains.

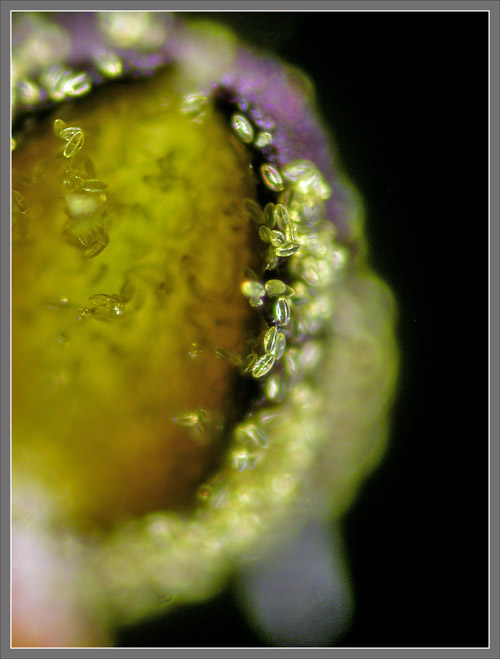

When the membrane has

completely

disintegrated and fallen away, the remaining anther appears

considerably smaller. Each anther has two pollen releasing

pads,

with a darker central section that is connected to the

filament.

This forms a sort of anther ‘sandwich’.

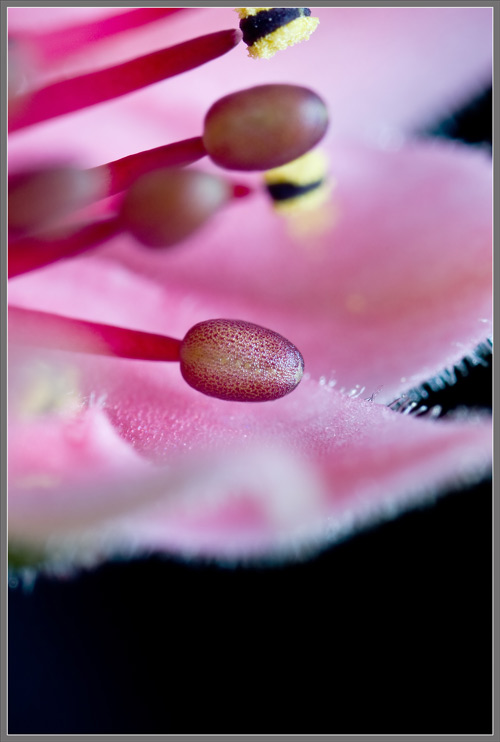

The slightest contact is able

to

dislodge pollen from the anther, as can be seen in an area where

one

has touched the surface of a petal.

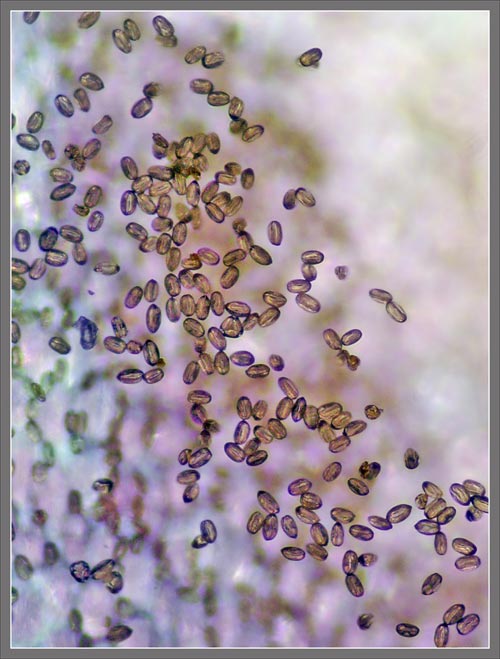

Below are photomicrographs

showing

the surface of a mature anther. The pollen grains can be

seen to

be ellipsoidal in shape.

Images showing pollen grains

adhering to the top of a filament (left), and the surface of a

petal

(right), can be seen below.

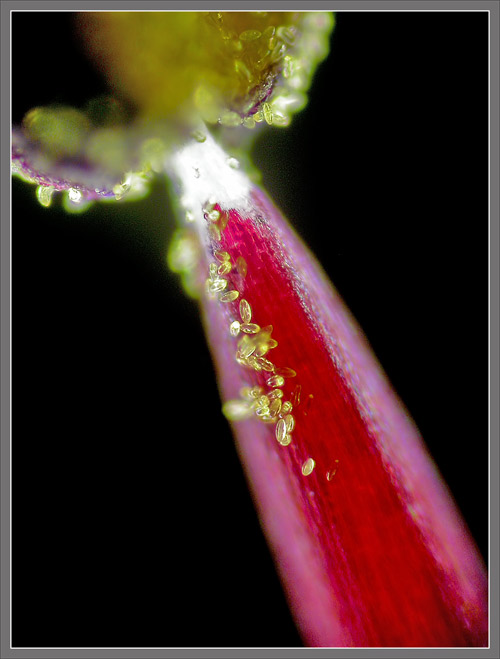

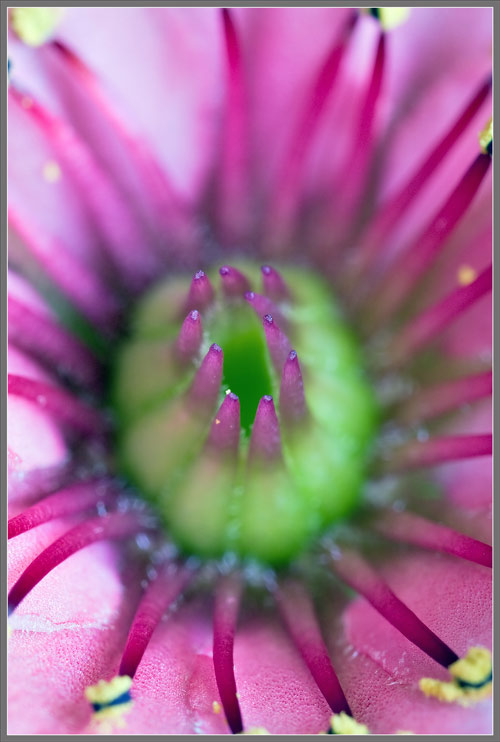

Ten bright red pistils, each

connected at its base to a pale green swollen ovary are visible

at the

centre of the flower shown in the two images that follow.

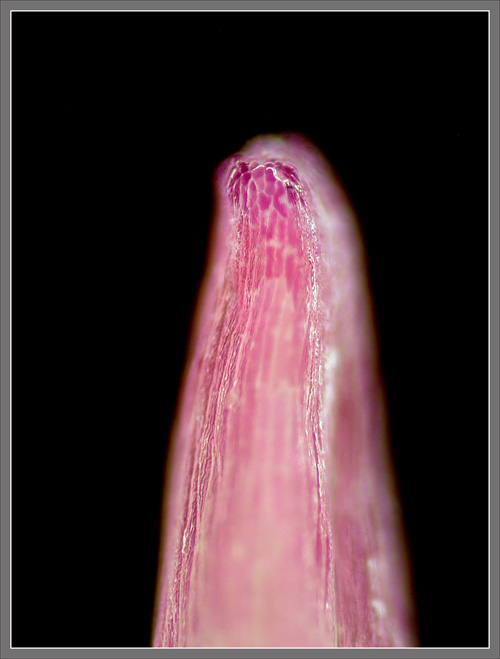

Under the microscope the

cellular

structure of the stigma and its supporting style can be seen

below. At the very tip of the pistil, the unusually short

lobes

that make up the surface of the stigma can be seen. In my

experience, these lobes are shorter than those in most flowers.

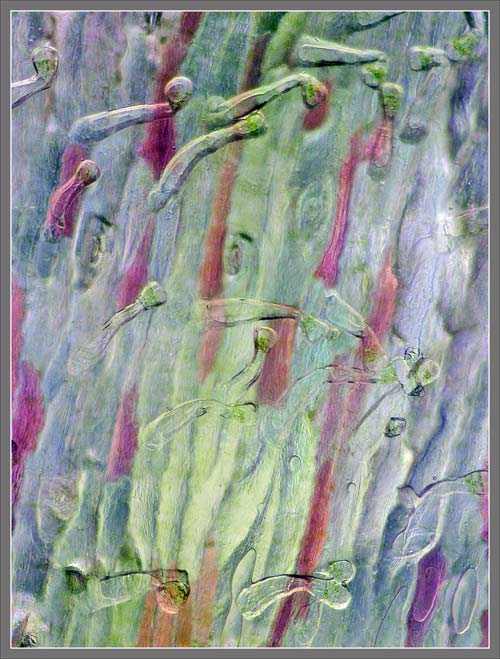

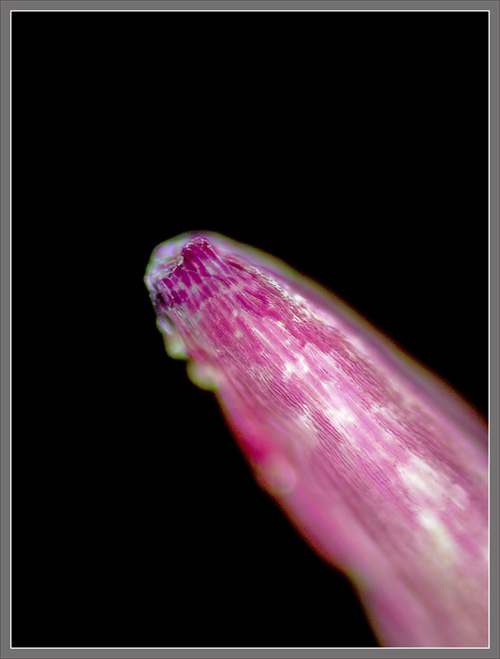

In the first image below, the

base

of one of a flower’s styles (red) is shown at the point of

connection

to its associated ovary (green). Note, in all of the

images, the

large swollen heads of the glandular hairs.

Hens and chicks are extremely

popular as rock garden plants. This popularity has

resulted in an

amazing number of ‘common’ names being given to the them.

A few

of them are: Houseleek, Jupiter’s Eye, Jupiter’s Beard, Thor’s

Beard,

Bullock’s Eye, Sengreen, Ayron, Ayegreen, Aaron’s Rod, Hens and

Chicks,

Liveforever, and Thunder Plant!!

Photographic

Equipment

The low magnification, (to

1:1),

macro-photographs were taken using a 13 megapixel Canon 5D full

frame

DSLR, using a Canon EF 180 mm 1:3.5 L Macro lens.

A 10 megapixel Canon 40D DSLR,

equipped with a specialized high magnification (1x to 5x) Canon

macro

lens, the MP-E 65 mm 1:2.8, was used to take the remainder of

the

images.

The photomicrographs were

taken

using a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser),

and

the Coolpix 4500.

A Flower Garden of

Macroscopic Delights

A complete graphical index of

all

of my flower articles can be found here.

The Colourful World

of

Chemical Crystals

A complete graphical index of

all

of my crystal articles can be found here.