WHO INVENTED THE

"ONION SKIN" BIOLOGY LAB?

Walter Dioni - Cancún, México

In Uruguay 70 years ago the epidermis of the inner

side of the scales of the onion bulb was the model used to teach me the

configuration of a cell, and I always imagined that it would be reported from years

before, on a global scale (in reality, "globally", taking into

account the scientific background of those years would mean (in alphabetical

order): England, France, Germany, United States).

I made a long review (and a much delayed one!) through

"search engines" and in the older texts of Botany, as well as the “Manuals for laboratory practices in Botany”,

published on the Internet Archive. I am not complaining. I could see, and

I really enjoyed the amazing skill of the artists, who filled those old books with

unbelievably beautiful images of plants and its parts, that rival (and many

times are better, if we discard the color) many current photos.

|

|

Selecting, I can provide the following data, limiting myself

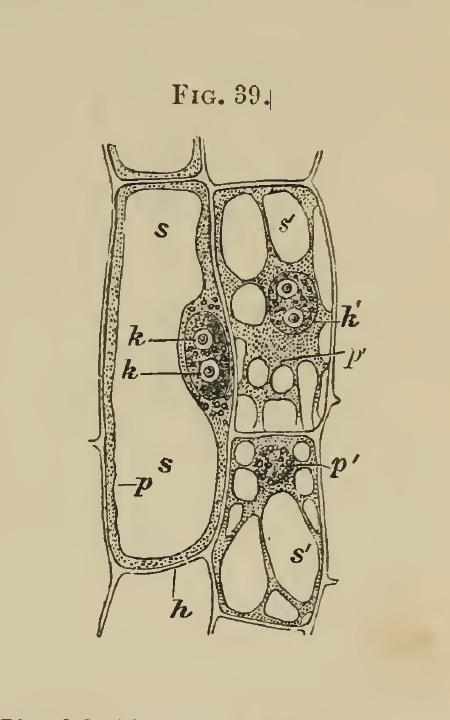

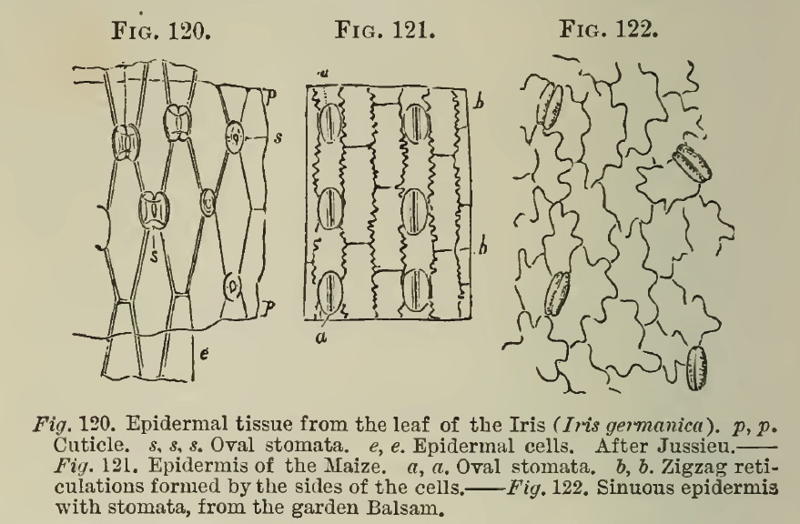

to the last quarter of the 18th century: He handles properly epidermis and cyclosis, and without using the humble and unknown onion, he shows Fritillaria cells in his fig. 39, describes and picture the cyclosis in potato stem hairs in fig. 40, and the cyclosis and chromoplasts in the aquatic Vallisneria leaf, and illustrates on page 58 the epidermis of Iris, maize (Zea Mais) and "garden Balsam"(Impatiens_balsamina). |

Also in 1887,

in the English translation of Strasburger’s

"Microscopic Botany", (pag 29, fig 15) the now classical onion

only contributes with its roots to the education of botanists. In 1889, Ch.E. Bessey in his “Botany”,

uses Fritillaria (p. 3, fig 2) and Tradescantia (p. 12, fig.7) cells in

some discussions. In his edition of 1896

of the same text, although citing the onion 7 times he is only interested in the

root.

Apparently his

books had not much success!

|

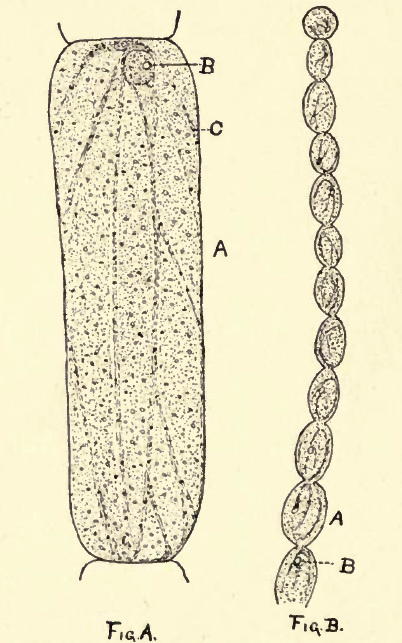

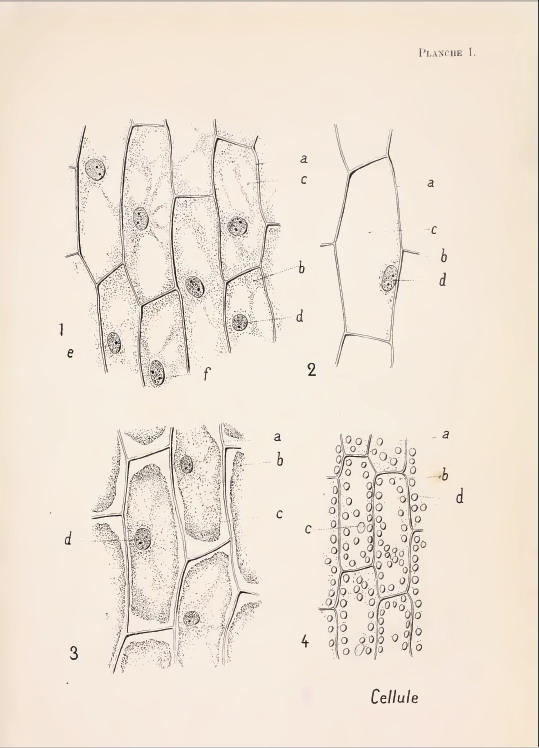

In 1894, Thomas & Dudley,

(Plate 1 fig 10, reproduced at right) used as a cell model those in the Tradescantia staminal hairs; the onion is

only quoted because of the crystals present in the outer epidermis of the bulb

(the tunica) |

|

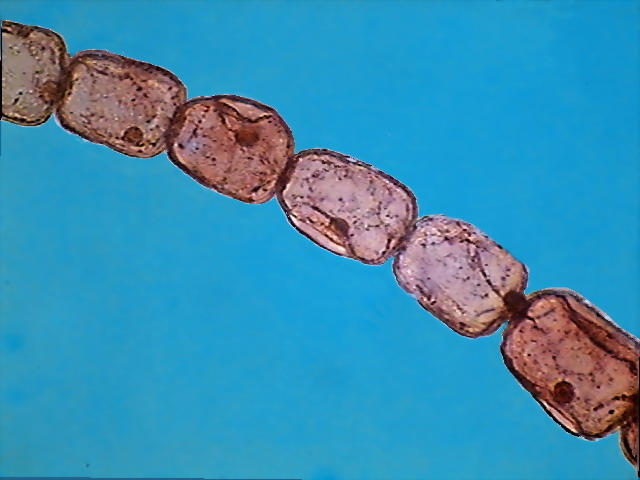

One portion of a Tradescantia

(Rhoeo) spatifolia, staminal hair. DC3 Motic Cámera

One cell from a staminal hair of Tradescantia

(Rhoeo) spatifolia, stained with eosin, from my work on “Eosin as a

nuclear stain”

http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artapr06/wd-eosin.html

Three marvelous pictures of a Tradescantia staminal hair taken though his DIC microscope, were published by Franz Neidl in:

http://photomacrography.net/forum/viewtopic.php?t=7581&sid=e13ee83d6786880a8a066b213dc2417d

Another beautiful rendition of this

subject is the one by Phil Gates in his blog:

http://beyondthehumaneye.blogspot.com/2009/05/jewels-and-sausages.html#comments

Invented by Georges Nomarski in 1950 the

DIC microscope has revolutionized the photomicrography, and become with justice

the favorite of now many microscopists.

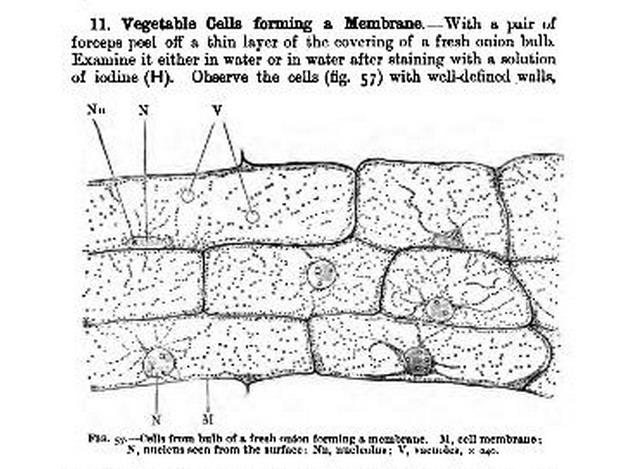

Interestingly a practical histology handbook mainly

dedicated to animal and human histology, Outlines

of practical histology, (2nd. ed.) W. Stirling, 1894, uses the "onion

skin" as an example of epithelium (fig 57, page 103)

In 1900 Clements & Cutter in his austere "A laboratory manual of High School

Botany" recommended cells of several different plants to display various

aspects of the same, but never the onion cells. Innovatively, to display the cyclosis

they recommended the hairs of the stem of young tomato plants (occasionally other

authors recommend (then and now) the cells of the pulp of the fruit of tomato

to display cells with coloured vacuoles, or the skin of the same fruit to show chromoplasts)

In 1921 J.E. Peabody, and A.E. Hunt, published their “Elementary

biology, plant, animal, human”. At p. 27 delineate their Lab.Study No. 21, which recommended the

use of onion skin (without the use of any colouring) to show the cell plant,

and then the use of Elodea leaf, to see chloroplasts and the cyclosis. In a foot note

we can appreciate the suggestion of "this wonderful material" by Mrs Elsie M. Kupfer, Head of the Department of Biology of the

Wadleigh High School, New York City, what suffices alone to show that even

at that time, 31 years after Bastin, the use of both materials was of little or

no use. In 1922, it is recommended,

in just 3 lines, the use of the onion skin in the book of A.G. Tansley, Elements of Plant biology, perhaps indicating a

tendency to generalize their use in Anglophone schools.

|

A Classic Subject for Study |

A DIC image of the onion epidermis, by Steve Durr, was

included in my “Homage to the onion skin” you can see it at this link:

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/artnov03/wdonion.html

This

is a picture of the floral cradles of Tradescantia

(Rhoeo) spatifolia- In the interior of the protective bracteae the little

flowers reach maturity one after the other.

One

mature flower of Tradescantia (Rhoeo),

showing the stamens, with its famous staminal hairs. The flower is only 5 mm

wide. Canon Powershot A300

Not for nothing do I record their use since the mid-18th

century, one hundred and thirty-five years ago.

The staminal hairs not only display all the structures of a typical plant cell,

but additionally allows an easy exploration of the cyclosis which my onion

cells show with difficulty, and even permit to watch mitosis in live, as these photos with a DIC microscope wonderfully

display.

http://www.life.umd.edu/cbmg/faculty/wolniak/wolniakmitosis.html

But "the tradescantias" are probably much

more difficult to obtain and maintain, and even to use (the stamen hairs are

very small items, and need to be picked from not fully developed minute flowers),

especially for its use in schools at a worldwide range, compared to the humble,

large, easy to manipulate and store, and always accessible onion.