|

Whimsies by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

No, this isn’t an essay on Lord Peter and his family, besides it’s spelt differently, but if you’re a fan of fine English mystery novels and if, by some miracle, you haven’t come across Dorothy Sayers, then you’re in for a treat. The only thing this piece has in common with Sayer’s novels is that, in a fanciful way, it’s about mysteries, microscopical and macroscopical mysteries. I decided to indulge myself in a bit of phantasmagoric fun and idle play, because lately I have found the regional, national, and world news so depressing–murder, rape, child abuse, individual and corporate greed on a phenomenally obscene scale; racial, religious, and ethnic intolerance; insane wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, the Congo, Somalia, Sudan, Lebanon, and Kashmir (to mention just a few); the mind-boggling, crass and craven stupidity of politicians, who are utterly indifferent to the suffering of the poor and infirm; the massive destruction of the environment of Planet Earth on which we must live or die, and the list goes on and on and on. So, I’ll stop; I’m getting depressed just writing the list.

Sometimes it’s necessary to turn off certain parts of the brain and go in search of some fresh air, quiet, and temporary tranquillity. Or, if you can’t get out, to lose yourself in your lab looking at some things you have been postponing examining. So, I warn you in advance, this essay is distinctly silly. It is difficult to be interested in natural history and not make rather strange connections between disconnected things. I am sitting here at the kitchen table on which there is a vase of yellow roses. A dried petal fell off onto the table and its shape reminds me a of a valve of a fossil brachiopod shell.

The human mind, when not being bombarded by someone chattering on a cellphone about Helen of Troy’s Hectoristomy or when not being assaulted by rap “music”, is capable of making intricate and fascinating associations. For example when I look at a specimen of the glass sponge called Venus’ Flower Basket (Euplectella aspergillum), I think about what a magnificent design it would be for a high rise tower and certainly its elegance would rival even the Petronas twin towers of Kuala Lumpur. However, if it’s ever built and you happen to live in its vicinity, you will have to accept the fact that the phraseology police will ban the expression: “I live just a stone’s throw from the glass tower.”

Children who are fortunate enough to develop an interest in natural history often give vivid and insightful descriptions of things they are trying to identify. Their minds have not yet been cluttered with categories and technical taxonomic jargon and so they sometimes present us with a new and fresh way of thinking about and seeing a particular object or creature. I have a suspicion that it was a child who first saw a lepidopteran and described it as a flutterby–this is the stuff of naive genius. As to how this got transmogrified into butterfly, I conjecture that it must have been a precursor of the Reverend Dean William Archibald Spooner, who once preached a sermon on the biblical text: “The Lord is a shoving leopard.” Speaking of butterflies, have you ever wondered how the scales manage to stay on the wings? I didn’t until recently. I was looking at a section of a butterfly wing from which I had scraped some scales (mostly C major and D minor).

I happened to be looking at a wing section with my stereo-zoom microscope while I was using a micro-scalpel and as I removed some scales I was amazed and delighted to discover that there are ridges that run horizontally across the wing and in them are minute “pouches” into which the tips of the scales fit, thus securing them to the wing. In the past I had always just assumed that butterflies used epoxy or Scotch tape to hld the scales on.

Butterfly wings are astonishing in a number of respects. If you have Lord and Lady Butterbottom coming to dinner and you want to make an impression, you can top off the salads with butterfly wings; they might be a tad crunchy, but if you select wisely the colorful display will so dazzle them that they won’t notice. And, in the course of the salad course, Lady Bertha Butterbottom might comment and query: “What clever creatures these butterflies! How on earth do they know how to arrange the colors on their wings?” Whereupon, Lord Basil Butterbottom, who studies theology at the University of Tierra del Fuego, says: Don’t be a ninny Bertie; God paints each one by hand before he releases ‘em.” Butterflies, of course, don’t “know” how to arrange anything; it’s all pre-programmed and genetically coded. Sometimes there are “errors” in the code and anomalies appear and, if it’s the right sort of anomaly–say one which produces “eye spots”, then it contributes to the survival of that mutation and we get a wonderful new thing to wonder at. The butterflies don’t notice, but we do.

They must lay a very large number of eggs. Butterfly eggs are quite intriguing and I’ve always wanted a slide or two of them, but I never had the patience to follow them around to see where they hid their eggs, not even on Easter. Many adult butterflies don’t live very long, so they must mate quickly and start producing countless eggs. The life spans vary radically and some only live for 2 to 4 days, whereas other can survive as long as 10 months. Butterflies have lots of predators including–in the days before cellphone, iPods, MP3 players, and video games–hordes of young boys with nets trying to add new specimens to their collections. Then there is also the toll which automobiles take on lepidopteran populations. Someday, I expect to see a headline in the National Inquirer : GIANT MOTH COLLIDES WITH CAR–VEHICLE DESTROYED!

The best way to get near perfect specimens is to collect the caterpillars, feed them until they form pupae and then hope to observe them as they break out of the chrysalis–what an experience! When I was a boy, we had wild carrot growing in the alley behind our lilac hedges. For several summers, I would go out and collect lovely, fat caterpillars which were munching away on the wild carrot leaves. These were the larvae of Tiger Swallowtails. I would put them in quart jars with lots of the plant for food and punch holes in the lids so they had sufficient air. Once the chrysalis had hardened, I check the jars daily. When the birth takes place, the by-now-brittle chrysalis cracks open and this alien and rather unprepossessing creature begins a life and death struggle to free itself. After a Herculean effort to escape its prison, it looks like it had a very bad hair day–in other words, it is wet and droopy and bears little resemblance to what we think of as a regal butterfly. Then something utterly remarkable starts to transpire. The wings, which are sodden and pasted against the body, are gradually pumped up; they are latticed with veins and as fluid flows into them, they “inflate” and then dry, presenting us with the magnificent display to which we should never become accustomed.

Once, when I was working on making slides of crystals, I got an image that looked like a small, alien butterfly floating near a blade of grass.

These are crystals of Potassium phosphate under polarized light.

Even more intriguing, lurking in some Ferric ammonium sulfate crystals, I found a multicolored elephant head.

The Hindu elephant god (Ganesha) must have designed this one in his (her, its) own image. Crystals, especially birefringent ones which produce colorful exhibitions when polarized, can unlock the imagination and one can project all kinds of patterns and forms into them. It reminds me of that game we used to play as children when on hot, humid summer days, our reserves of energy depleted, we would stretch out on the grass and discover dogs and lions and birds, and, of course, a dinosaur or two in the cloud formations slowly drifting high above us.

We heavy-footed, earth-bound beings are fascinated with those creatures which can soar, glide, and hover in the air. Hummingbirds, giant condors, moths, hawks, wrens dragonflies, bats, owls, and even the wretched mosquitoes and flies all amaze us and cause us to dream; I would even like to have seen a pterosaur. To climb into a multi-million dollar machine is not at all the same as what we describe as flight in nature. I find neither Heathrow nor O’Hare a source of exhilaration.

Dragonfly nymphs are formidable predators and do look like something out of a science fiction monster movie. They are fairly easily maintained in a small aquarium and it is fascinating to watch them stalk their prey; they can move in slow-motion and then freeze completely so that you might not even notice them. When they are in position, their jaw apparatus moves out with lightning-like rapidity and the only way you know that anything has happened is that the prey has disappeared.

When these strange creatures have undergone metamorphosis, they become aviators of extraordinary beauty. They can hover, dive, zoom, snatch a mosquito out of the air (Bravo!) and even mate in flight! (Bravissimo!) Their wings are elegant networks of delicate veins.

Imagine designing aircraft with wings like that which give the plane the remarkable versatility of movement and maneuverability which a dragonfly possesses. Their cousins, the damselflies, are small and very lovely and anyone who takes up pond watching should certainly pay them close attention.

As I sit here again at the kitchen table, scribbling away–the yellow roses which I mentioned at the beginning have been discarded, having lost their petals–I look up at a vase of white and yellow carnations, their edges delicately trimmed with vibrant reds. They make me smile and I think of the beautiful sentiment which Iris Murdoch expressed:

“People from a planet without flowers would think we must be mad with joy the whole time to have such things about us.”

Botanical illustrators have now, for several centuries, painstakingly revealed to us the subtle and intricate beauty of plants and particularly flowers. Georgia O’Keefe has riveted our attention on these marvels in splendid, colorful canvases. New technologies provide us with means to probe even further into the secret realms of flowers as is strikingly revealed in the superb photographs of Brian Johnston, who has provided Micscape readers with wonderfully revelatory articles.

Technology also provides us with lots of intriguing objects to examine under the microscope. Until 10 years ago, I had never looked at a computer chip.

These days such a chip is regarded as primitive, but the geometry of it I find quite pleasing.

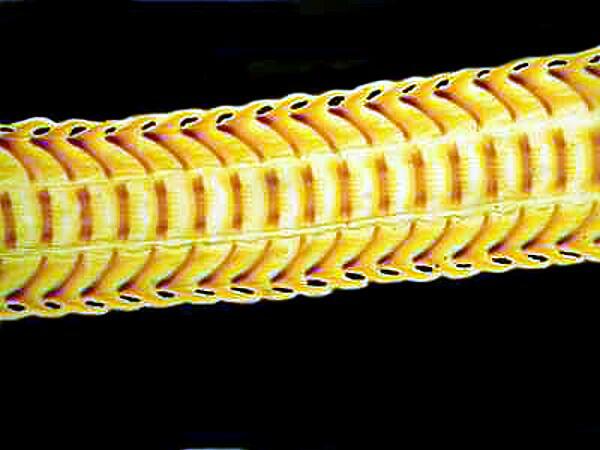

However, even low-tech objects such as Velcro can prove interesting.

The hook piece rather reminds me of a snail radula (the tongue with teeth).

These are used for scraping algae off surfaces which the snail uses for food–quite an elaborate device for a vegetarian.

Last year I came across an advertisement in a popular science magazine for a science fiction film and included was a pull-out holographic image. so, I pulled it out and put it under my stereo microscope. Here are some views of what I saw.

It makes me think of what we might produce if we tried to do high-tech simulations of butterfly wings with scales. Maybe someday we’ll get a lot closer, but we’re by no means there yet.

The world has countless hidden marvels for us to discover if we allow our curiosity and imagination to develop. Even then nature will continue to astonish us by providing new surprises thus giving us new things to wonder about.

For a long time, I have wondered about flatfish. A little baby flounder has an eye on each side of its head like most fish, but as it grows, one eye migrates so that it lies on the bottom with both eyes looking upward. However, it has another remarkable ability; its skin is filled with chromatophores which can be rapidly arranged is such a way that they provide the fish with a camouflage that matches the background on which it is lying at the moment! Now, the eyes are much more flexible in their sockets than ours and these fish may have terrific peripheral vision, but I don’t think that they can see the background for the full extent of their bodies. So, the question is: How do they “know” how to rearrange the chromatophores to match the background of the moment? I frankly admit that I don’t know, but if I had to guess, I would say that there may be light sensors embedded throughout the skin which convey the relevant information to the chromatophores. After all many of the functions that take place in the human body are not immediately and directly processed by the brain–that would take too long–rather, powerful stimuli can be recorded and reacted to by neural clusters in the spinal cord. Just as a side note, squid and octopi are undoubtedly the champion chromatophore manuveurers and even seem to use colors to express emotions. However, they require an essay all their own.

Light sensors are abundant in the natural world. We find them in Euglena, Daphnia, Planaria, the succulent Homarus (yummy lobster), the 8-eyed arachnids, in the tips of the arms of starfish, and, of course, there are the stunningly sophisticated eyes of squid and octopi.

One afternoon I went out to our side porch where the mailbox is and beside it was a small jumping spider. I have long been intrigued by these little creatures, so I went into the kitchen where I keep a stock of small jars to capture any specimens that have the misfortune to wander my way. I must say that I was highly impressed by the visual acuity of this little creature. I felt almost as though we were playing a game. Every time I would move the jar toward it, it would scuttle aside. We repeated this 8 or 10 times and then, he or she, being smarter than me, had had enough and jumped completely out of range. Extraordinary vision, but I wouldn’t want to have to buy glasses for myopic spiders.

Almost everyone has heard of electric eels, but did you know that there are also electric rays and, no, I’m not talking about tasers or Tesla coils. Years ago, when I bought some 5 gallon buckets of preserved shrimp trawl trash, there were, in the marvelous melange 2 wonderful specimens of Narcine brasiliensis, an electric ray. How are they able to generate a substantial electrical wallop? Well, once a month, they have to jump out of a tidepool and mug the Energizer Bunny. Actually, Narcine does have a kind of battery, two in fact, one located in each wing. Amazingly there are clusters of stacks of modified muscle and nerve cells and small calcareous plates which act like the plates in an automobile battery. Some of the electric rays can generate potentials of 50 to 500 volts and are dangerous to humans. Again and again, nature beat us to it. Imagine what we could learn and invent if we spent billions of dollars studying plants and animals instead of building colossally destructive weapons so that politicians can claim that spinoff technologies of military investment bring great benefit to all mankind. Sorry, I promised to remain whimsical.

There are some creatures whose very presence on this planet bring us a sense of delight and feeling of belonging to a wider community than that of mere humans. Orchids, meerkats, giant sequoias, pandas, roses, and otters–all of these seem to be celebrations of life. And how difficult it is to resist baby kittens, puppies, baby foxes, lion cubs and, yes, even baby skunks. Human babies, however, as someone rather cynically remarked, all look like Winston Churchill.

However, there are those among the human species who help redeem our monstrous, egoistic destructiveness and even though these creators are themselves imperfect and full of contradictions, they provide clues to how me might transcend our baser natures. What would the world be without the Beethoven Triple Concerto, a superb Chateau Margaux, the sonnets of Shakespeare, Dostoevski’s The Brother Karamazov, Mozart’s, Piano Sonata for Four Hands K. 381, the paintings of Veermer, and Bach’s Goldberg Variations?

As for nature, we must learn to cherish it and not simply exploit it. We should be able to exult in the elegant ballet of a fairy shrimp, marvel at the flamboyant display of the peacock, and emulate a child’s first wondrous encounter with a buttefly. But first to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Henry VI: “Kill all the mosquitos!”

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to shares aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .