|

|

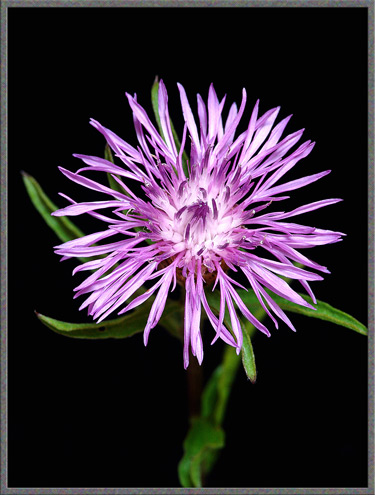

A

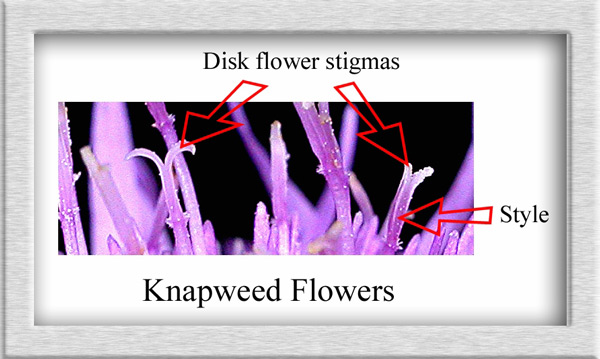

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Centaurea jacea) |

|

|

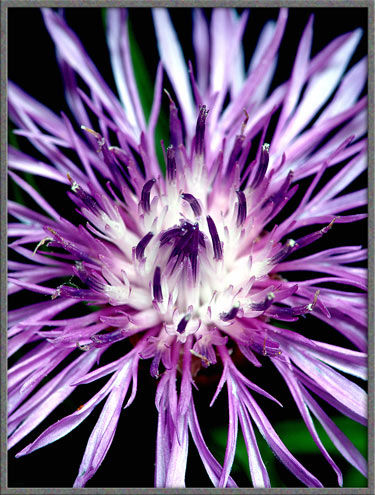

A

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Centaurea jacea) |

Some

wildflowers are ubiquitous. Dandelions, thistles, Queen Anne’s

Lace, and many others can be found by simply looking around while out

of doors. Others are harder to find. Although several

varieties of Knapweed exist in Southern Ontario, their growth

requirements limit the number of locations where they can be found.

Brown Knapweed, the subject of this article, requires fairly cool,

moist locations. It originated in Europe and was brought to North

America by immigrants. Most Knapweeds are considered aggressive

and invasive plants, and this is particularly true for the two

commonest species, Spotted Knapweed and Brown Knapweed.

The plants are members of the ‘Aster family’, whose flower-heads are composite (an aggregation of small

individual flowers), containing both ray and disk flowers. The

genus name Centaurea

comes from Latin, and refers to Centaur Chiron who studied the

medicinal uses of plants. The species name jacea comes from

the Spanish name for Knapweed.

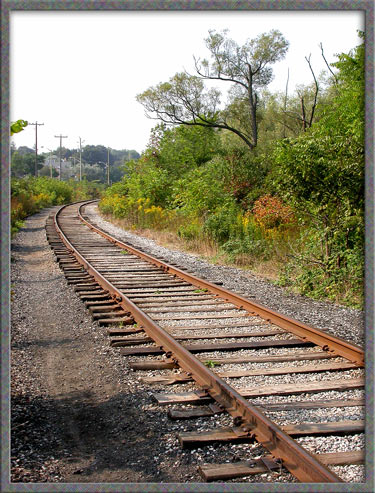

I have looked for, but never found Brown Knapweed in Toronto where I

live. Success was achieved while walking along the train tracks

which border a river in the town where I grew up (Hespeler). At

one point, the tracks pass through a limestone rock-cut. Not more

than two metres from the tracks, I found about 100 plants in bloom,

most growing up through the crushed stone stabilizing the wooden ties

that support the rails. I was astonished to find that all of the

plants were growing on one side of the tracks. Not one Knapweed

was to be found on the other side! (The condition existed again

this year, so more than just chance must be causing this

situation.) The image below shows the general location of the

plants, although the photograph was taken in early Fall, after the

plants had stopped blooming.

What sets the Knapweeds apart from other plants is the extremely

unusual series of modified leaves called bracts beneath the

flower-head. As can be seen in the image below of a bud, these

bracts are brown and look almost textile in nature. (The tips of

the bracts are light brown or beige in Brown Knapweed, and almost black

in Spotted Knapweed.)

Highly magnified, the intricate structure of a bract becomes

visible. Note the many ‘legs’ that seem to emanate from the

‘bug-like’ body.

In the bud shown earlier, all of the bracts are tightly layered to the

developing flower. For some reason the bud below seems to be

having a ‘bad hair day’!

As the flower-head begins to bloom, the topmost bracts are pushed aside

by the petals of ray flowers as they extend upwards.

A closer look at the base of the previous flower-head shows that each

bract is composed of a lower green striped section, and an upper brown

‘insect-like’ section.

Higher up, the brown parts are so tightly packed, that the lower green

portions are completely obscured.

The topmost bracts, just under the ray flowers, have a different top

that looks distinctly ‘comb-shaped’.

At first, the central area of disk flowers, (the white tubes) is small.

Later, all of the disk flowers are in full bloom. Note that they have

darkened to just slightly less pink than the outer ray flowers.

The unique bracts certainly set the Knapweed apart from other members

of the aster family.

The petals of the outer ray flowers of most composite flower-heads are

simple rectangular ribbons. In this species, they are much more

complex.

Under some conditions, the ray flower’s petals are curled almost into a

tube (first image). At other times, they flatten out as in the

second image.

Brown Knapweed has a ridged stem that is usually striped with narrow

purple bands. The upper leaves, as seen in the two images below,

are lance-shaped and are connected directly to the stem (without a

stalk). Leaves have a concave upper surface and become

progressively smaller the higher they are on the stem.

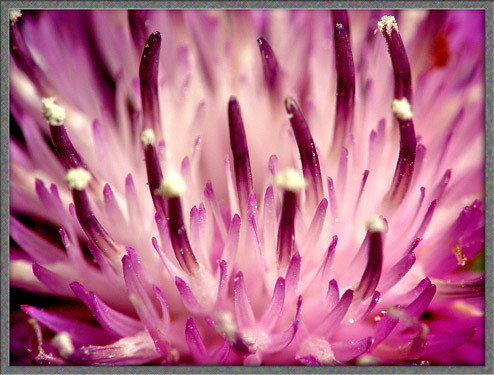

The first flowers to bloom in the composite head are the outer ray

ones. Only later do the central disk flowers open. The five

tiny petals of each disk flower are white in the images below. At

this stage, the stigma and style (female, pollen accepting

structures) are not visible. The dark purple tube extending from

each flower is formed from the five anthers

(male, pollen producing structures), which are fused together.

Using

higher magnification, it can be seen that many of the anther tubes have

a collection of pollen grains at their tip.

To produce the following image, I deliberately focused on the tips of

the disk flower petals, rather than on the anther tubes projecting out

of them.

Growing up through the tube formed by the five fused anthers is the pistil, composed of the stigma and

style. Note that each stigma has two curved lobes.

With a microscope it is possible to obtain even higher

magnifications. The first image shows two of the five anthers

forming the tube. Some pollen grains are visible at the tip of

the tube.

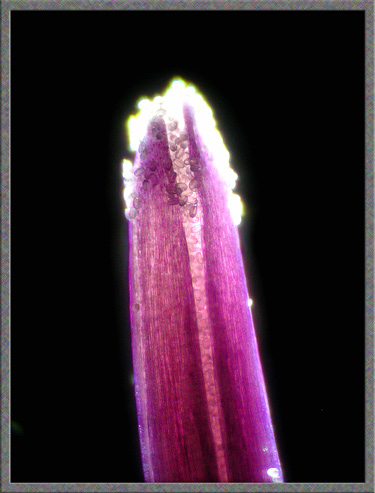

This second image, (using a slightly lower magnification), shows a

later time when the pistil has grown up out of the anther tube.

The two lobes of the stigma have not yet appeared.

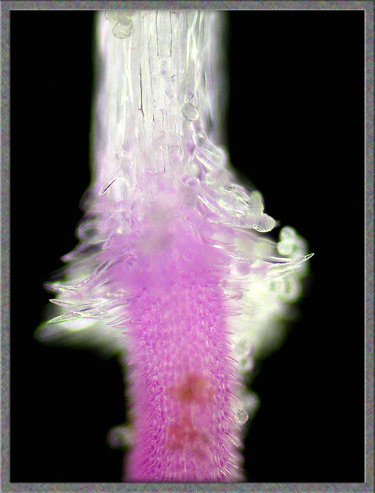

The pink structure below is the style which supports the stigma.

The stigma is the colourless structure. At the joining point

there are a number of hair-like projections which hold pollen grains.

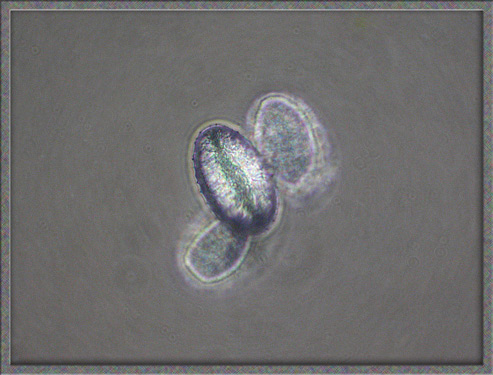

Pale yellow-white, egg-shaped pollen grains are visible stuck to the

surface of the style.

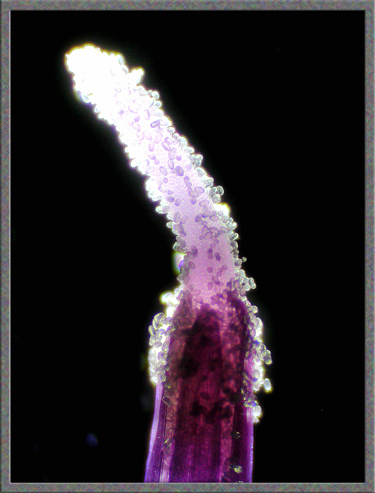

As the bi-lobed stigma matures, it becomes darker red in colour.

This photomicrograph shows pollen attached to the branching point.

A higher magnification phase-contrast image of a pollen grain shows the

egg shape, and a line (groove?) that bisects the grain longitudinally.

Like many wildflowers, Brown Knapweed has a variety of alternative

common names. Common Knapweed, Star-Thistle, Brown-Ray Knapweed,

Harshweed and Knapwort are just a few. My personal favorite is the

Welsh name for the species, Y

Bengaled Llwytgoch. The problem is that I don’t know how

to pronounce it!

Photographic Equipment

The photographs in the article were taken with an eight megapixel Sony

CyberShot DSC-F 828 equipped with achromatic close-up lenses (Nikon 5T,

6T, Sony VCL-M3358, and shorter focal length achromat) used singly or

in combination. The lenses screw into the 58 mm filter threads of the

camera lens. (These produce a magnification of from 0.5X to 10X

for a 4x6 inch image.) Still higher magnifications were obtained

by using a macro coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4

Olympus SLR lens to the F 828. (The magnification here is about

14X for a 4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz

SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix

4500.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

Published in the March

2006 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1996 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .