A Strongylocentrotus

drobachiensis by |

I want to talk about two basic issues in this essay: 1)

scientific names and 2) taxonomy or classification systems. Strongylocentrotus

drobachiensis is the name of a green sea urchin. It's not a

very big animal and even including the spines, it ordinarily

isn't more than 6 inches in diameter. I once read that this is

the longest scientific name for any organism. Whether this is

true or not, I hesitate to mention it for fear that it might

prompt a contest among biologists to come up with longer and

longer names. Reputedly, there is an annual contest in Germany to

come up with the longest compound noun which makes sense. Years

ago, one of my German professors reported that one of the

contenders was

Oberammergauerpassionsfestspielklosterdelikatsfrühstücksükäse

(a cheese made in a monastery as a breakfast delicacy for the

Passion Play at Oberammergau). So, this is clearly not a trend

that one would wish to encourage in biologists and perhaps

particularly not in German biologists.

Spirostomum ambiguum is a protist which rarely exceeds 2

millimeters in length. Perhaps there ought to be a rule that the

size of an organism should play a role in the length of the name.

One suspects that at one time bacteriologists must have had been

plagued with a sense of mediocrity since they were studying some

of the smallest organisms and yet they invented some of the

longest names. When they find some nasty pathogen, this seems to

bring out their nomenclatural worst. Consider Staphylococcus

hemorrhagicus, Streptococcus erysipelatis, and Plasmodium

cathemerium. But invertebrate biologists are no better

regarding such matters. A small flatworm has the intimidating

name of Rhynchomesostoma rostrata which it carries

around on its 5 millimeter back. An even smaller flatworm bears

the hefty moniker Geocentrophora sphyrocephala! And then

there's a rotifer only 350 microns long called Wierzejskiella

ricciae—I dare you to say that fast ten times. And, if

you're interested in copepods, you'll certainly want to be able

to distinguish between Maraenobiotus insignipes and Ergasilus

centrarchidarum which ought to be easy since Ergasilus

is parasitic on the gill filaments of fish, but only if it's in

its adult stage and only if it's female. Even plants don't escape

these nomenclatural abuses; there is a vascular freshwater plant

with the lilting name of Myriophyllum alterniflorum.

Having taught university students for 35 years and having

observed the decline in their vocabularies and abilities to use

language properly, I have often urged a return to the

old-fashioned curriculum that requires Latin and Greek. However,

whenever I think about the linguistic excess of taxonomists, I'm

not so sure that, after all, that is such a good idea.

Ostensibly, scientific names were once designed to be

descriptive.

Certainly the name Chaos chaos for the giant amoeba is

distinctive and descriptive. Spirostomum ambiguum is

descriptive in part: "the one who is spiral-mouthed and is

ambiguous". Well, I don't know quite what's ambiguous about

this particular organism as contrasted with a whole lot of other

beasties, but, perhaps, whoever named it really meant to indicate

that it is mysterious, in which case its name is ambiguous and it

probably should have been called Spirostomum mysterium.

One might ask why we don't just follow the simple procedure of

giving descriptive names in our native language. After all, if

the Catholic Church could go from the Latin mass to the mass in

English, Urdu, Swahili, Japanese, etc., then why not do something

parallel for scientific names? Well, the answer's obvious, isn't

it? We'd come up with something like "micro-whale" for Spirostomum

and the Germans would launch "das

Zirkelmundbandformiggrünblauigsüsswasserkleintierchen" for

the same little beastie and win a prize in the annual contest.

Sometimes there are very good reasons for standardization.

Nonetheless, the biological nomenclaturalists could be more

considerate.

A major problem for the microscopist is that few of the organisms

in which we are interested have common names. Bird watchers can

talk about cardinals and orioles and nuthatches and magpies and

gimlet-eyed tidwatchers (sorry, sometimes I like to make up names

myself) or fish enthusiasts speak of betas and angelfish and neon

tetras, whereas we are left in the situation of enthusing over

spine cross sections of Strongylocentrotus drobachiensis,

which, by the way, are quite splendid.

We humans like to know where things fit and so we invent

classification systems. So, the microscopist can say, protozoa

are animals and algae are plants—right? Well, no not

anymore. I recall a children's game called Twenty Questions. One

person thought of an object and the others could ask twenty

questions that could be answered yes or no in order to try to

guess the object. The one who thought up the object had to tell

the others if the object was animal, vegetable, or mineral. These

were simpler, although not necessarily better, times. I suspect

that botanists used to feel inferior, like second cousins,

because generally speaking, trees are not particularly

dramatic—they don't run or jump, swing or

growl—although there are "weeping" willows. So

when something as exciting as Volvox comes along and

it's got chlorophyll, well, naturally the botanists want to stake

a claim to this magnificent organism. But the zoologists had

their aesthetic sensibilities finely honed too, and pointed out

harshly, that plants don't swim, and so, the famous chlorophyll

vs. swimming debate began. As a consequence a lot of rhetoric was

flown high and a lot of ink spilled.

Then in the last decade or two, some biologists decided to try to

resolve some of these difficulties, and as is usually the case

with such compromises, made things much more complicated and

created a whole new set of conflicts and debates, some of which

are so heated that certain biologists are barely on shouting

terms. Whereas previously we had just three major

categories—animal, vegetable, and everything else—we

now have six: monera, fungi, protista, animal, plant, and

everything else. However, some people don't like the name

"protist" which comes from the 19th Century German

biologist, Ernst Haeckel, and have proposed instead the term

"protoctista"—what an ugly word! At the very

least, it should be protictoctista (pro-tic-toc-tista). A word to

biologists: Watch your language! Many of the old terms were

descriptive and evocative—Stentor is good; it looks

like a trumpet—Lacrymaria olor, "tear of a

swan" is poetic, but Strongylocentrotus drobachiensis

for some wonderfully spiny little urchin—come on! And

"Protoctista" is a first-rate abomination. However,

whether you refer to this kingdom by Protoctista or Protista,

it's one of the most motley collections of organisms imaginable.

Browse in the Handbook of Protoctista and you'll encounter

beasties that are stranger than anything in science fiction.

Protist is a Humpty-dumping-ground category; if the object in

question doesn't fall into the monera, fungi, animal, plant, or

everything else categories, then it clearly belongs to the

kingdom Protista.

In the Handbook of Protoctista, there are listed 79

classes under 35 phyla, although the two classes in the last

phylum are of rather uncertain status due to a paucity of

information.

The phyla are then put under 4 major headings with a fifth for

those last two classes:

I. NO UNDULIPODIA; COMPLEX SEXUAL CYCLES ABSENT

II. NO UNDULIPODIA; COMPLEX SEXUAL CYCLES PRESENT

III. REVERSIBLE FORMATION OF UNDULIPODIA; COMPLEX SEXUAL CYCLES

ABSENT

IV. REVERSIBLE FORMATION OF UNDULIPODIA; COMPLEX SEXUAL CYCLES

PRESENT

V. INSERTAE SEDIS

(from pp. xiii-xiv)

SEX, SEX, SEX, SEX. That's all these biologists seem to have

on their minds. As Elsa Maxwell once said: "Too many people

have sex on the brain—and that's no place for it." But

before we get to the good stuff, we need to talk about this bit

of jargon "undulipodia" or "little waving

foot"—sounds rather like a parody of an American Indian

name, doesn't it?

The senior editor, Lynn Margulis' first two sentences under the

heading of "Terminology" are: "The senior editors

and contributors nearly came to blows concerning aspects of

terminology. We are dealing with the collapse of the walled

structures of academic disciplines such as protozoology."

(p. xii) Undulopodia is the term which Margulis wants to

substitute for cilia and flagella (which are "nearly"

identical) in eukaryotes. The application of the term flagella

would then be restricted to "extracellular",

"intrinsically nonmotile" organelles of prokaryotes.

Confused? It gets worse. "Mastigote" is now to be the

new term for the "traditional flagellates".

And this is only the beginning. It get's really quite

interesting. For a very long time, protozoa have been described

as single-celled animals. However, some recent biological

taxonomists have tried to move away from that description by

creating an entirely new kingdom for a large set of groups of

organisms that have never quite comfortably fit into the

traditional plant-animal distinction, in other words, the

Protista, which we have been talking about. One of the virtues of

this approach is that it obviates the long-standing dispute

regarding whether certain organisms, such as chlorophyll-bearing

flagellates are plants or animals. Historically, some of these

organisms have been vigorously claimed by the botanists and

equally passionately claimed by the zoologists. Some of these

disputes have had the intensity of the medieval theological

debates over the categories of Being which led to street fights

between monks. Isn't that a provocative image! As one might

expect, this new approach to classification has not resolved all

of the problems. The publication in 1990 of the Handbook of

Protoctista involved four chief editors and over 60 major

contributors world-wide. In the introduction to this volume, Lynn

Margulis states: "Even today, many scientists (e.g.,

especially cell biologists, plankton ecologists and geologists)

routinely write about Protozoa and Algae as if they were phyla in

the Animal and Plant kingdoms, respectively. These organisms are

no more 'one-celled animals and one-celled plants' than people

are shell-less multicellular amebas." This is a radical

challenge to a long-established tradition, but one which is

supported by many very eminent scientists. However, this general

agreement still produces some significant differences of opinion

about both classification models and terminology.

As we mentioned above, one particularly intense battle centered

over the attempt to replace the words "cilia" and

"flagella" with the term "undulipodia."

Somehow I find it rather comforting that scientists as well as

philosophers can still get so passionate about such arcane

matters that have so little to do with a practical world in which

most of the people have never even heard of, let alone observed,

a cilium.

The more I have studied micro-organisms, the more sympathy I have

developed for the view that denies saying that protozoa can be

accurately described as "one-celled animals," but the

less patience I have for the excesses of overzealous taxonomists.

One thing that becomes clear rather quickly is that the four

major groupings listed above (using the criteria of undulipodia

and sexual cycles) are arbitrary. They may turn out to have a

high degree of utility and so become standardized until the next

taxonomic "revolution," but we always need to remind

ourselves that these are human inventions for our own

convenience. As a boy of 15, I was much taken with taxonomy and

used to make elaborate charts tracing the evolution of

invertebrates. They were, of course, naive, but they did help me

understand certain problems and I came to think of taxonomy as a

way of clarifying the relationships between organisms. Not any

more!

There is a dilemma regarding this kingdom of Protista. Remember

those wonderful 19th Century volumes which had incredibly long

explanatory subtitles—well, that's true for the Handbook

of Protoctista as well. Sometimes old habits die hard. Here

is the full subtitle, "The Structure, Cultivation, Habitats,

And Life Histories Of The Eukaryotic Microorganisms And Their

Descendants Exclusive Of Animals, Plants, And Fungi: A guide to

the algae, ciliates, foraminifera, sporozoa, water molds, slime

molds and the other protoctists." This sounds like a parody

of a Victorian tome on Natural History, but, go look, and you'll

find I didn't make any of it up; it's all there and an ambitious

subtitle it is too.

There is a lot going on in this subtitle. Note that it excludes

fungi, but includes water molds and slime molds, so you can bet

that if Dr. Margulis had her way, we would see some even more

radical terminological surgery. Just think what's being said

here: we have molds that aren't fungi; algae that aren't plants;

ciliates, foraminifera, and amoebae that aren't animals! Some of

these protists are freshwater, some are marine, some are

estuarine, some are terrestrial, some live on snow banks, some

live in thermal pools, some are parasitic, and some can survive

for decades in cysts. They range in size from organisms that

measure slightly less than 1 micron to the giant kelps that can

exceed 100 meters. There are creatures here, like the sporozoans,

that generally lack anything that we would readily identify as

behavior to ciliates like Urocentrum turbo which are

absolute dynamos whipping through the water at breakneck speeds.

One could go on and on about the differences, but the real issue

is: what do all of these diverse organisms have "in

common"? In the introduction to the handbook, Margulis

admits the following: "Unfortunately no neat definition

encompasses all the protoctistan diversity, except a definition

by exclusion." (p. xvi)

As weak as this sounds, it really shouldn't surprise us too much.

The world is an exceptionally complex place and sometimes we tend

to forget that and trying to put things in order to help us

understand these complexities is no easy task. We have to devise

methods of grouping things in ways that are useful. Imagine a

system in which we classified everything according to color. We

would, of course, have to have specialists and soon the

specialists on things "red" would be involved in heated

disputes with specialists on things "orange" and on and

on. To what point? There generally isn't any utility in

classifying things according to color.

So, when thinking about classifying things, we have to think

about utility and also recognize that such systems are going to

get more and more complicated as we learn more and more about the

things we want to classify. We also have to learn to ask the

right questions. I used the phrase "in common" a bit

ago and this has been one of the major difficulties about

classification schemes and it is a difficulty which we inherited

from Plato and Aristotle. Early philosopher-scientists were

looking for a neat system of definitions which would be expressed

as a series of criteria stating the essence of what something is.

For example, Plato once defined man as "a featherless

biped." Diogenes of Sinope, the Cynic, plucked a chicken,

walked into Plato's lecture room, held it up and said: "Here

is Plato's man." So, you can see that difficulties about

classification have a long history.

But back to the issue of "in common". We might ask what

a Paramecium has "in common" with a giant kelp

that allows us to classify both as protists? — May I have

the envelope, please! — The answer is: nothing. Well,

nothing very useful anyway. We can say that they're both alive

but so are plants, animals, and fungi and Dr. Margulis certainly

won't let us use that as a criterion for sneaking those into the

Kingdom of Heavenly Protoctists. They both live in water. Well,

so do whales. Clearly, we need a different sort of approach.

The philosopher Wittgenstein came up with a notion called

"family resemblance" which might be helpful in

understanding some things about classification. However, take

note—this idea has nothing to do with the fact that you may

look very much like your brother, especially if you're identical

twins. Rather than looking for a set of criteria which groups of

things have in common, we instead look for shared or connected

criteria which allow us to assert a relationship. This sounds

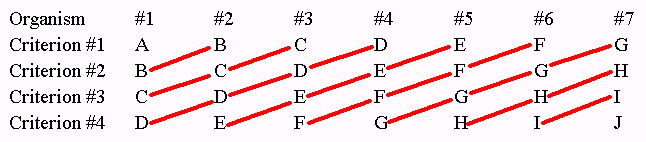

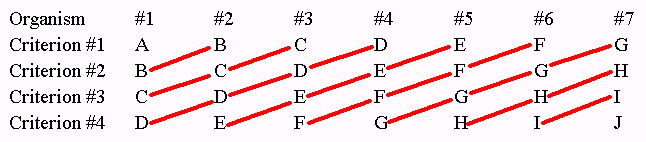

rather murky, but the basic idea is quite straightforward. Below

is a greatly over simplified example, but it will serve to

illustrate the essential point.

| Organism | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #6 | #7 |

| Criterion #1 | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Criterion #2 | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

| Criterion #3 | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

| Criterion #4 | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

Notice that organism #7 has no criteria in common with numbers 1,2, or 3. However, it does have one criterion with #4, two criteria with #5, and three criteria with #6. Note further that numbers 4,5, and 6 do share criteria with numbers 1,2, and 3. The shared criteria become more evident if we draw some diagonals in our diagram.

When one considers that there may be hundreds, even thousands, of criteria involved in the classification of an organism, then one begins to appreciate the difficulty of the task. The kingdom Protista (or Protoctista) is a stop gap measure. As we learn more about these organisms and discover yet new ones, categories and criteria will change. We need to remind ourselves that there are tens of thousands of organisms which we have yet to discover. In the meantime, the protists are a wondrously bizarre collection of organisms that challenge us and remind us that the basic sense of astonishment at the variety of nature is the foundation of both philosophy and science.

Epilogue

Whoops! We forgot the stuff about sex. It's probably just as well. Sex in protists is far too complicated and interesting to gloss over in just a few paragraphs, so I promise I'll devote a future essay to this topic.

Comments to the author Richard Howey welcomed.

Editor's notes:

The author's other articles on-line can be found by typing in

'Howey' in the search engine of the Article Library, link below.

Published in the June 1999 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK