Most everyone who gets interested in having even a modest selection of slides for study and reference eventually comes across some Victorian papered slides. I use the term “Victorian” here more as an indicator of a certain style of slides than as a literal historical period. There are, after all, slides surviving from the 18th Century and papered slides from the 20th Century. Some of the early slide makers were extraordinarily ingenious in the materials they used. Some used strips of beautifully grained polished boxwood, mahogany, oak, pine, and even rosewood. Small scraps of such woods could be obtained from fine furniture makers and were fashioned into a variety of types of slides. Today the standard size is 1 inch by 3 inches or 25mm by 75mm but, in earlier times, no such standard ruled. If one had a lovely 5 inch strip of mahogany, why cut it down to some smaller size, which not only increased the work, but increased the risk of splitting the wood so as to make it unusable. The piece might also, in fact would likely, be wider than one inch. Thus, pragmatic and aesthetic considerations dictated trying to make the best use of the piece of wood with a minimum of modification.

Now, if you have fashioned the corners and polished the surface, why drill just one hole in the center to mount a single specimen? Sometimes that was done but, more frequently, multiple holes were made allowing for a handsome display of 3, 4, or 5 specimens. And all of this before power tools! The care and precision which such work demanded was enormous, but that is what craftsmanship is all about–an attitude which is all too rapidly disappearing. Sometimes the wooden slide would be thick enough that the maker could make the holes go only part way through the slide. The bottoms of the holes could then be smoothed and either painted or papered to provide a contrasting background for the specimens. In the days of the very early slides, thin glass, such as we take for granted now in the form of cover glasses, was difficult to obtain, expensive, hard to work with, and often contained flaws. As a consequence, some of these slides will have thin sheets of mica as a cover with a thin metal ring or clip (usually brass) to hold it in place over the specimen in the cell or hole. Such slides were, of course, used for mounting opaque objects and had to be illuminated from the side or at an angle from above.

In other slides, the hole would be drilled all the way through the strip of wood and the specimen was then mounted between two slips of mica, or later on, thin glass. The virtue of this sort of arraignment was that the specimens could be seen from both sides. Certain types of objects could be especially advantageously displayed in this manner, such as, sections of butterfly wings, wherein the upper surface and the under surface may possess startlingly different patterns of scale arrangement and coloration.

Microscopes were a luxury and the grinding of lenses, the production of brass tubing, the designing and manufacture of stands, mirrors, stages, and other accessories was a major feat involving a variety of types of craftsmanship. What this meant is that persons who owned microscopes were moneyed, if not necessarily, aristocratic. Enormous economic changes had taken place with the rise of a wealthy merchant class whose social status was primarily determined by their fortunes. At one time in Victorian England, there was a popular bit of fictitious lore that every Gentleman owned both a microscope and a telescope. The cost factor extended, of course, to the production of slides–slides that were aesthetically attractive, unusual, containing bizarre or beautiful specimens and made from handsome or exotic materials commanded high prices. Among those who were able to have microscopes, there was often a human-all-too-human competition to have the best microscope, the best and latest accessories, and the best slides. Just consider the microscope done in silver by George Adams for King George III. You can see pictures of it here:

A wealthy, often titled, English gentleman would invite his friends to his estate for a fine dinner accompanied by splendid wines and then provide an after-dinner entertainment by showing off his latest slides. (No doubt this was a relief from the frequent recitals of his daughters exhibiting the results of their expensive singing lessons.) The more unusual the slides in both subject and composition, the greater the boost to his ego and so he was often willing to spend an exorbitant amount for a single slide. Even today, there are collectors who will quite literally pay hundreds of dollars for a single slide and some who amass enormous collections and often the pleasure of mere possession is more important than any real examination or researching of them. I am reminded of a colleague of mine at the university who is a bibliophile. Both he and his wife teach and both have a considerable amount of money independently so that neither of them would really have to teach. He has a large personal library of rare and expensive books and he admits that he already has, although he is only in his mid 40s, more books than he will ever be able to read or use in his lifetime either for pleasure or research. For him, the acquisition, the owning has become the primary passion. From historical and psychological perspectives this is not surprising. Think of the tomb of Cheops, the sarcophagus of Tutankhamen, the palace of Versailles, Buckingham palace, Neuschwanstein of Ludwig the II of Bavaria, San Simeon, the William Randolph Hearst castle in California–all monuments to monumental egos. The cost of the objects collected to furnish or decorate these sites is astronomical, so why should it be any different in the realm of microscopy except, of course, the scale is much more modest in its excess. I can never think of the pyramids without bringing to mind Thoreau’s scathing remark which I”ll share with you here:

“As for the pyramids , there is nothing to wonder at in them so much as the fact that so many men could be found degraded enough to spend their lives constructing a tomb for some ambitious booby, whom it would have been wiser and manlier to have drowned in the Nile, and then given his body to the dogs.”

Fine slide makers did not, by any means, limit themselves to the medium of wood upon which to mount their specimens. Pieces of bone were cut, shaped, polished, and drilled and produced some very handsome mounts. However, as you can well imagine, mounters vied with one another for both more exotic mounting materials and more exotic specimens. The natural history business was booming and special expeditionary vessels as well as ordinary trading ships brought back enormous quantities of curiosities for both museums and private collectors.

Slides were made from sections of tortoise shell, which apparently was rather difficult to work up for slides, since such slides are quite rare. Occasionally even strips of metal were used to make some rather odd slides. However, one of the most exotic and expensive materials was ivory and these slides were much sought after. Often such slides were narrow strips of a length up to about 6 inches with multiple cells for mounting highly attractive and unusual specimens. What would be the point of having a slide made of such an extraordinary substance to display prosaic and bland specimens?

To be a commercial maker of fine slides in the 19th Century was a demanding and highly competitive enterprise. Imagine trying to procure hummingbird feathers, peacock feathers, rare moths and butterflies, bits of exotic minerals and gems, sections of tropical plants, unusual seeds, pieces of rhinoceros horn, fragments of corals and the list goes on and on. At the same time, significant advances were being made in micro-technique which opened up a whole new universe of possibilities in terms of preparing and presenting specimens.

The advent of less expensive, simpler, and smaller microscopes along with the appearance of the Polariscope extended the types of specimens which mounters offered and expanded the range of those who developed an interest in acquiring a microscope. There were, of course, no nice convenient plastic Polaroid filters in that period. Polarization was achieved through the use of specially cut pieces of clear calcite and were called Nicol prisms. It was also discovered that thin strips of selenite or mica could be used as compensators. What this meant was that a wide variety of crystals on slides were presented for the discerning viewer. Many crystalline substances which looked quite plain under ordinary illumination now displayed a riot of color under the Polariscope. The transformation was by no means limited to crystals. Hairs from humans, animals, and even plants were revealed to be birefringent. Sections of bone, rhinoceros horn, calcareous spicules of sponges, corals, and sea cucumbers and rock sections, all contributed to the opening up of a new microscopical territory when viewed under polarized light. In fact, it became common for mounters to add labels to their slides indicating which ones were good subjects for the Polariscope.

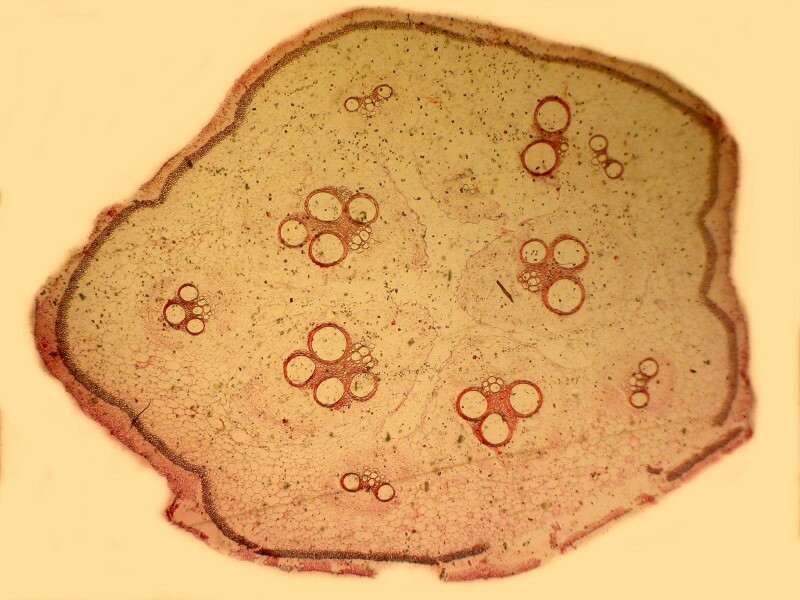

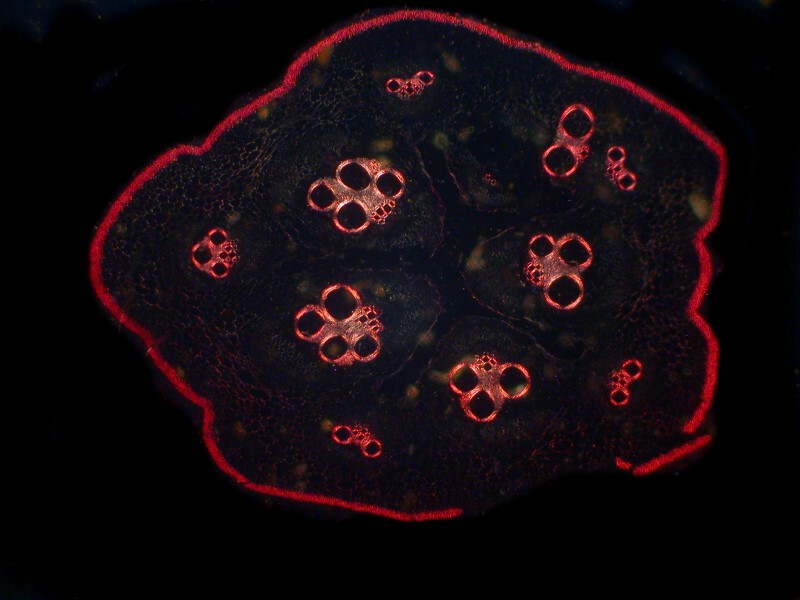

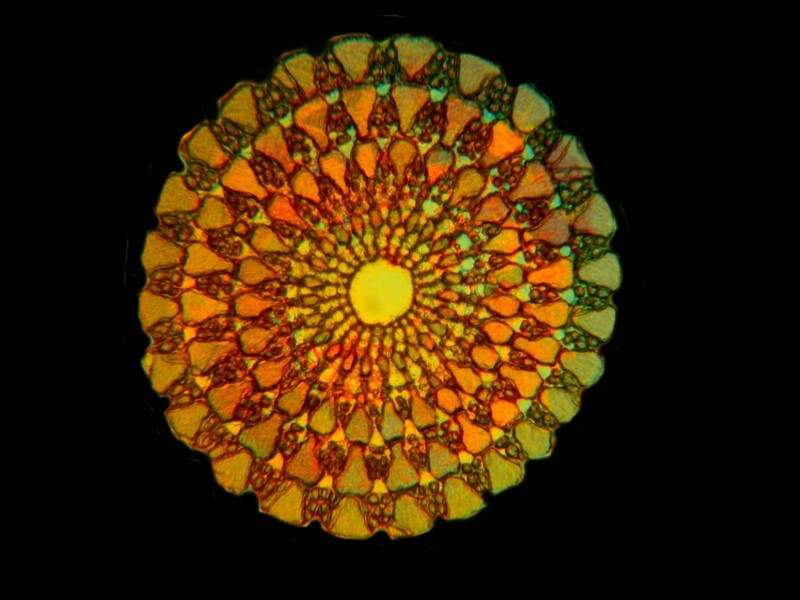

As the techniques in microtomy advanced, the production of thinner and thinner sections of both botanical and animal tissues led to new and innovative techniques involving the use of stains. Some of these techniques were simple and straightforward, whereas others, over time, developed into complicated, demanding, and highly sophisticated means for differentiating and identifying specific cytological and histological structures. Experimentation with such techniques was particularly intense during the last half of the 19th Century and the first half of the 20th Century. Many stained sections also produced spectacular results with polarized light. I’ll give you 2 examples here. First Cucurbita–this is a cross section of a pumpkin stem in brightfield and then polarized.

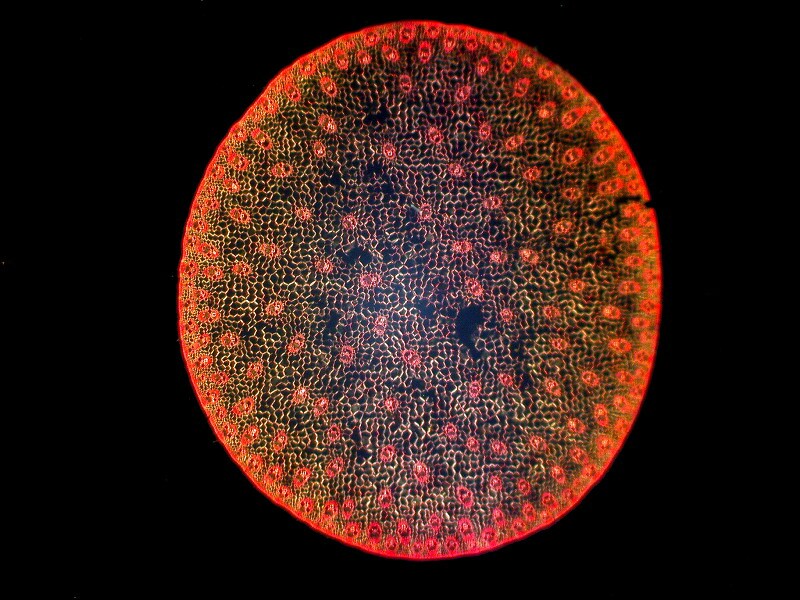

Second Zea Mays–this is a cross section of stem of corn in brightfield and tghen polarized.

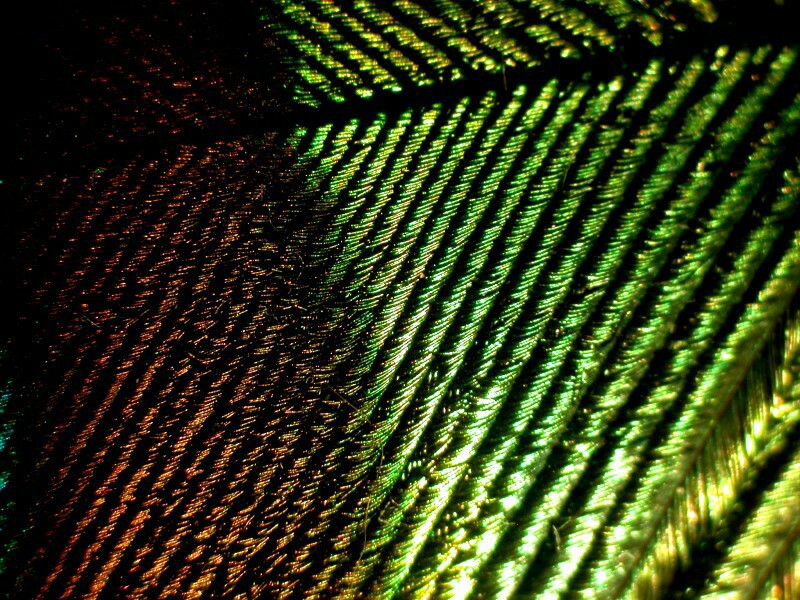

A number of these techniques involved the use of 2 or even 3 stains often producing highly colorful results. In other cases, some mounters concentrated on objects which did not require staining. There were certain objects which became highly popular, among them the mouth parts of a blowfly, the gorgeously colored, metallic-looking bits of a peacock feather, copepods with feathery appendages and, of course, cross sections of sea urchin spines.

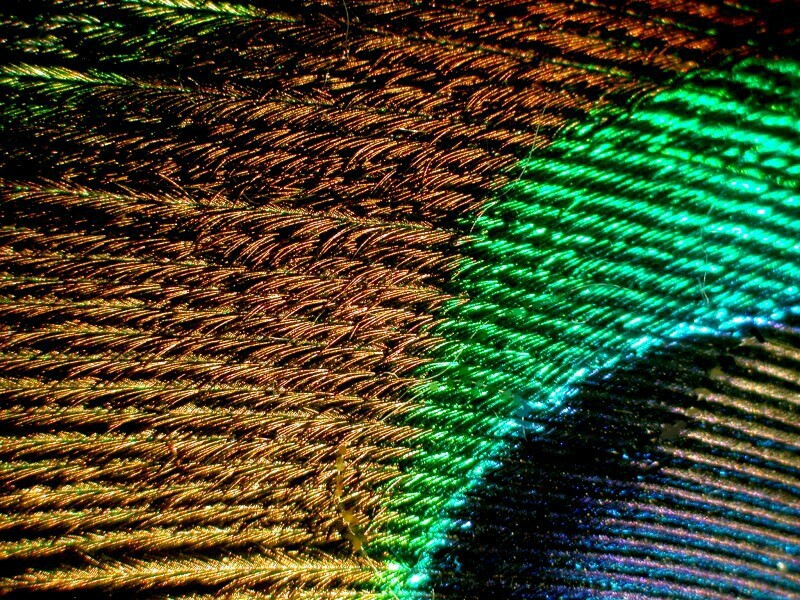

First, a view of a part of a peacock feather with a seam of 2 colors.

In this next view, we can see how there seems to myriads of tiny wires the compose the rows creating an illusion of a metallic surface.

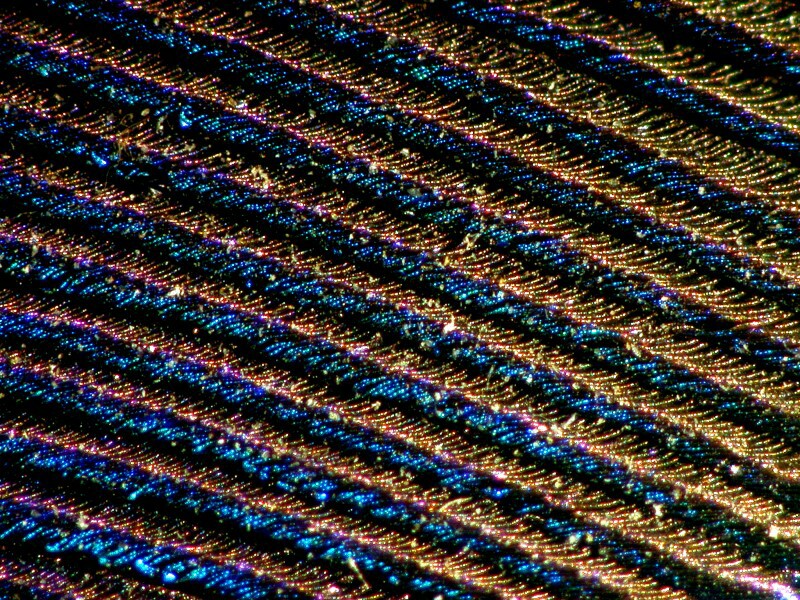

In the third view, we can see the magnificent interplay of color between the light brown strips and the deep blue ones.

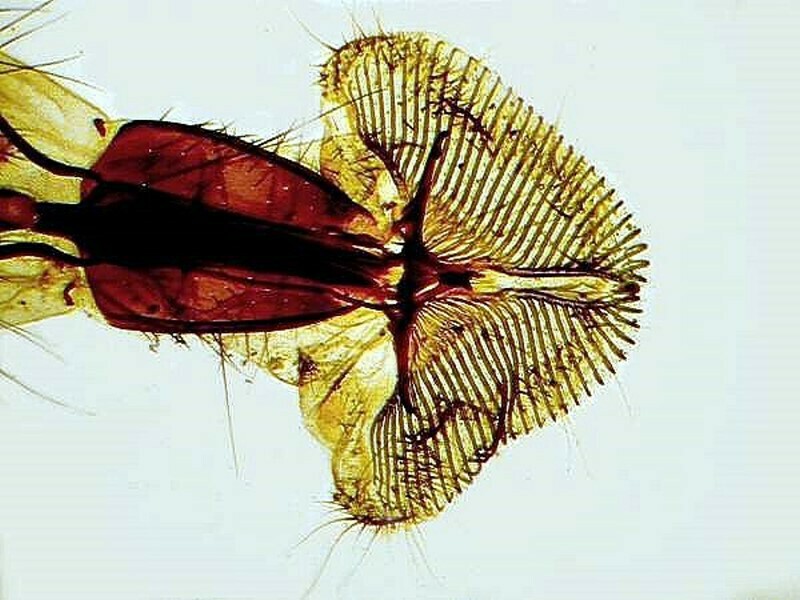

Now, let’s take a look at an incredibly elaborate structure–the mouth of a blowfly. Clearly, this is not an easy object mount with such clarity. This is am image taken from a 19th Century slide using brightfield.

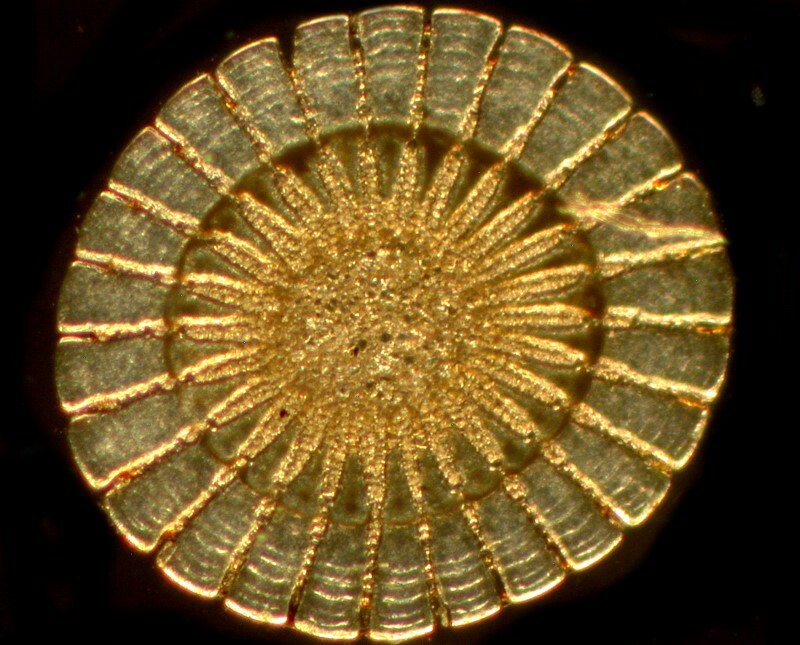

I can’t resist including 3 image of cross sections of sea urchin spines. Producing these is the sort of thing that can drive a man mad; they are extremely fragile and susceptible to breakage when you are trying to prepare them.

This first one reminds me of a bronze shield; perhaps it belonged to a micro-Achilles.

This second image shows that some of these sections are indeed highly birefringent.

The third image gives you a clue into the incredible number of tiny crystalline structures that comprise this spine. All three of these images were taken using polarization.

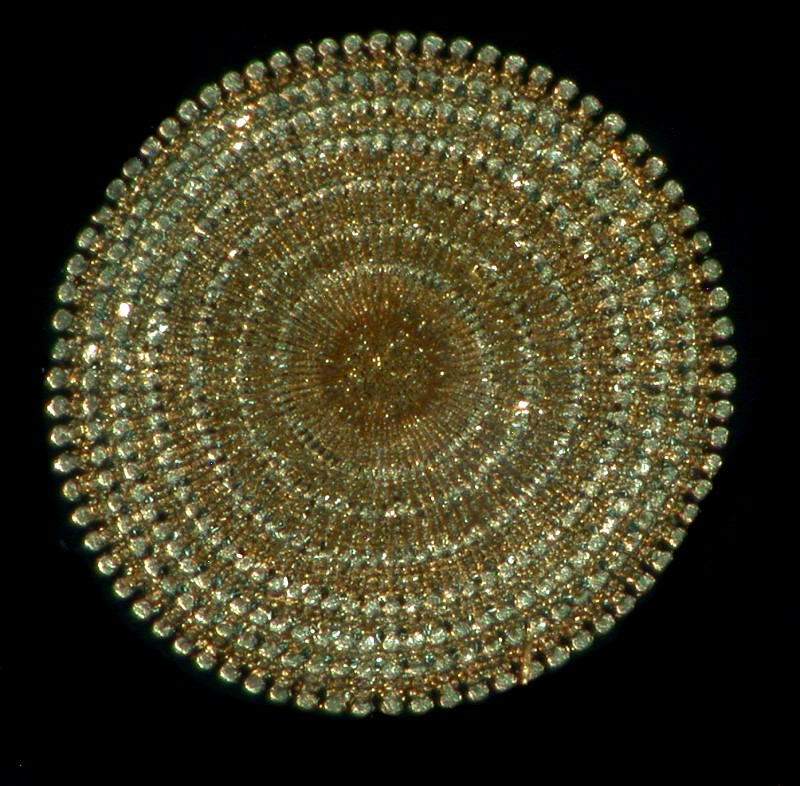

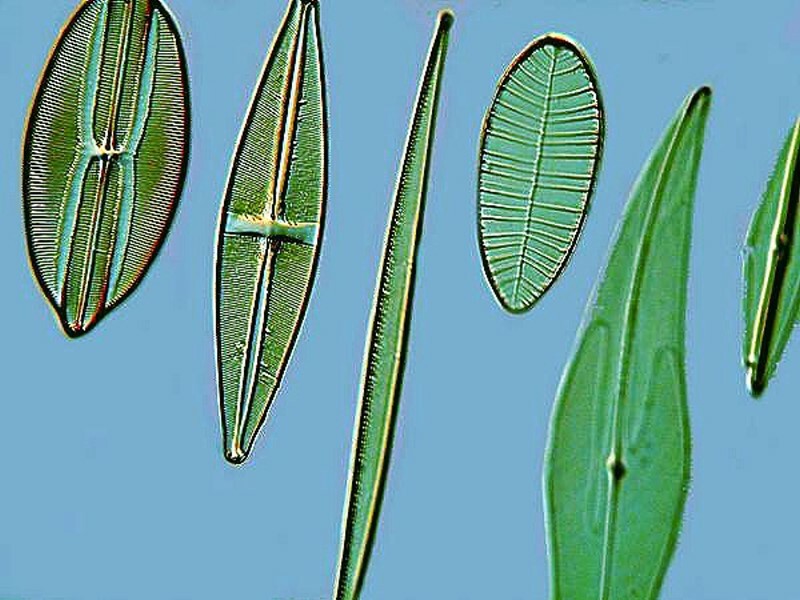

There was another type of slide that was in great demand and brought high prices–the slides with groups of objects arranged in patterns. So, what is so special about that? Let’s begin with diatoms–microscopists are mad for diatoms and with good reason. The “shells” of these tiny protists (which used to be regarded as plants) are made of silica (glass) and have minute rows of dots, the density and size of which varies from species to species. Some of them are so fine that only the very best (and most expensive) lenses can resolve them and so, diatoms are often used to test the quality of lenses. These slides were made of selected diatoms in a row, ranging from those which could be readily resolved with any decent medium power lens to those diatoms with finer structure in each succeeding specimen until, at the very end of the row, was a specimen which only the very fine, high power lenses could resolve. Such slides were invaluable for manufacturers and purchasers in assessing the quality of lenses. Such slides are still produced and are very useful. The number of diatoms in a row varied and the one which I have consists of 12 specimens closely aligned in a straight line. (I should mention that there are more ambitious ones which have several rows.)

Here is a closeup of some diatoms on such a test slide.

Well, you might think, how hard can that be? Picking up individual diatoms, let alone getting them to stay where you want them to on a slide or cover glass, is no easy task. Try it. There are some special little tricks and techniques which make it easier, but I”ll let someone else explain those.

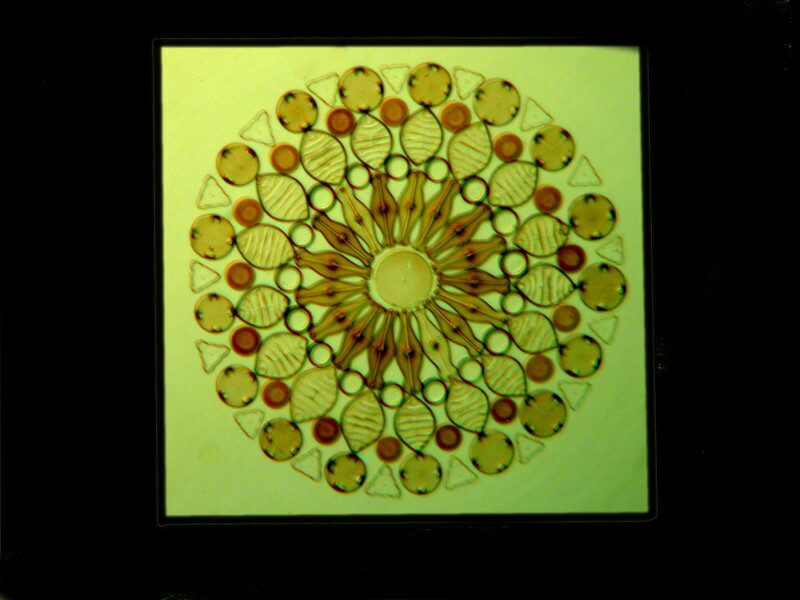

However, what we are interested in is not just a handful or two of diatoms in a straight line, but a significant number laid out in a circle or a rosette. Imagine a rosette pattern which is a mixture of centric (circular) and pennate (canoe-shaped) diatoms built up from 25 individual specimens. Better yet, here’s an image of such an arrangement.

Many even more elaborate ones were produced and you can see a few examples at the following site:

Now you can bring your imagination into play. The production of such slides with hundreds of individual specimens arranged in a pattern was time-consuming and presented nightmarish possibilities for making missteps. As you can well imagine, such slides are still highly sought after and command remarkably high prices. Not all of these arraignments have remained in pristine condition. In some instances, a few diatoms may have shifted position due either to improper storage, exposure to heat, an inferior batch of Balsam, or a misstep on the part of the mounter. However, unless the displacement of the diatoms is on a rather large scale, such slides still remain quite valuable.

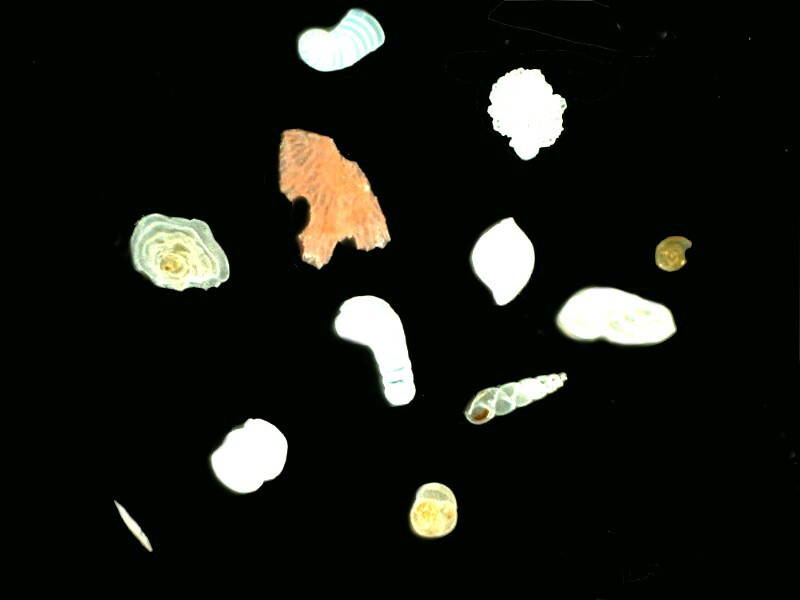

Forams were also frequently mounted in arrangements, but they were generally less elaborate, foram shells usually being considerably larger and thicker than diatoms. A specialist in England, Brian Darnton, has produced some wonderful mounts of forams and is helping to preserve an important aspect of the tradition of natural history though his splendid slides. He has also produced some wonderful mounts of fern scales and I’ll show you an example of some forams which he kindly sent to me some years ago and a slide on which he did an arrangement of fern scales.

These forams are from Malta and I placed them in a drop of immersion oil to increase contrast. You can find a discussion of that technique in my earlier article “Forams and Oil” which you can find here:

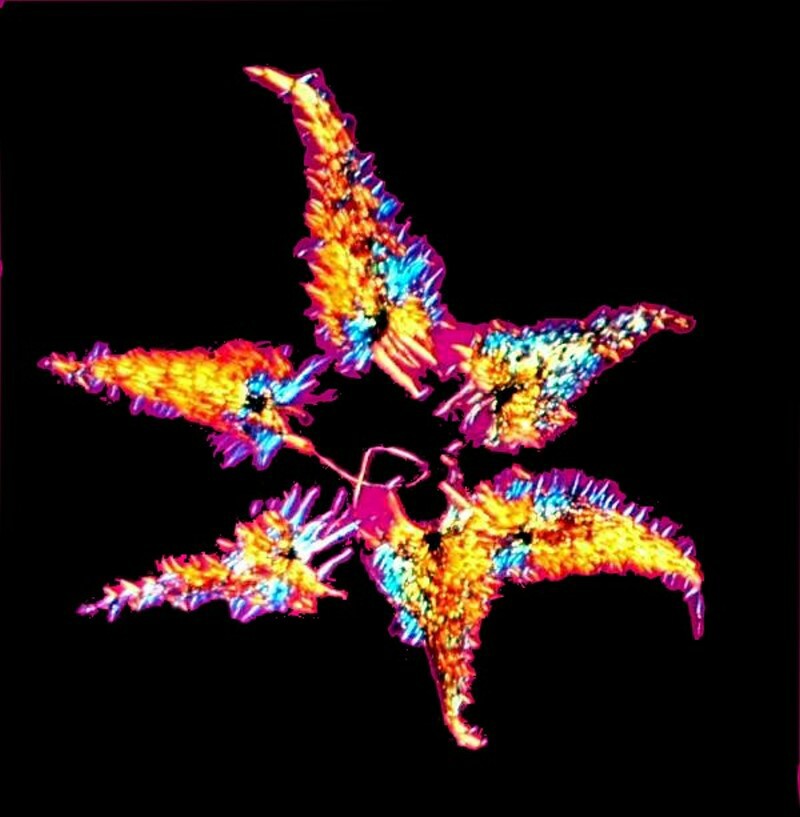

As you can see fern scales are wonderfully birefringent objects and are splendid candidates for polarization.

Another popular subject for arrangements was plant seeds. They were, of course, like foram arrangements, opaque mounts. Sometime the seeds were packed together so densely that they formed a handsome circular arrangement that was almost kaleidoscopic in nature. Recently such a slide sold on an internet auction for over $100.

Spicules of various types were also used both for strews and for arrangements. A strew is much easier to produce, since it consists of spreading a drop of concentrated sponge, echinoderm, diatom, or radiolarian material thinly over a very clean cover glass. With a strew, there is no concern about pattern or arraignment. However, when using spicules some striking arraignments were produced and they also command hefty prices.

If you think all of the above is hard work, well you’re right, but an even greater challenge remains–the arrangement of butterfly scales into patterns, not merely rosettes, but into miniature scenes of floral bouquets. Klaus Kemp has kept this tradition alive, creating wonderful diatom and butterfly arrangements which equal or surpass many of the older slides. You can find examples of his work at : http://www.diatoms.co.uk/

Although these slides are not inexpensive, given the quality and complexity of the work, they are certainly not exorbitant and constitute a very good investment. The diatom rosettes and the butterfly scale floral arraignments I find quite lovely and I very much appreciate the remarkable technique involved in producing such slides. Mr Kemp has reportedly set for himself a personal challenge of creating a diatom arrangement with 400 specimens in it. He is certainly to be commended for keeping this demanding art alive and inspiring others to do so as well. Geographically far removed from England, Dr. Stephen Nagy has also been producing splendid diatom slides inspired in part by Klaus Kemp. Here is an examples of Dr. Nagy’s work. http://montanadiatoms.tripod.com/

To me, it is enormously pleasing that there are individuals who are still dedicated to preserving the creation of such microscopical marvels.

I’ve been rambling on again and haven’t even gotten to the central topic of paper slides, so I’ll stop here and make that the theme of Part II for the next issue.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the June 2015 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .