|

An Overview of Human Cells for Light

Microscopists |

|

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 For Part 1 The Human Cell - go here! Part 2 Human Skin - go here! |

|

| Insect Eyes Insect's View: Simulation1 Simulation2 Simulation3 Human Eyes1 Human Eyes2 Resources and external links | |

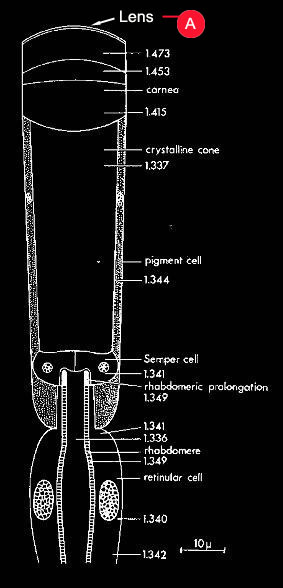

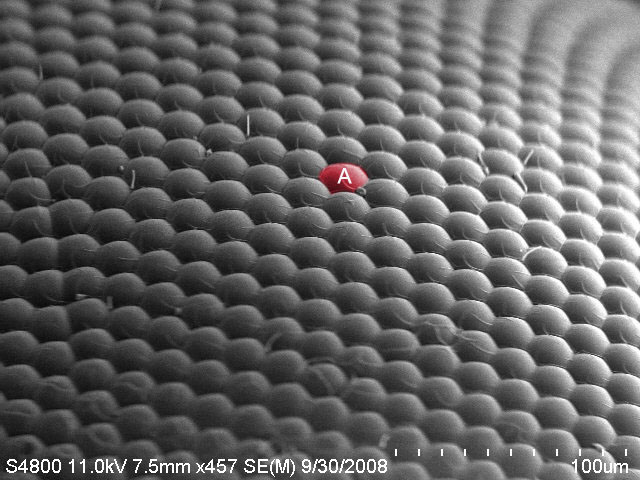

| Human Eyes & Insect Eyes The most important thing to a light microscopist is his/her eyes. This comes as no surprise because probably, the most important thing to nearly all living entities of the animal kingdom, including insects, is sight. Nature has developed several solutions to the problem of aiding living entities to navigate their reality by detecting light (or other) waves reflected by objects and subjects in the environment. I thought it might be interesting to explore two of these methods here by looking at the human eye and a compound eye - as exploited by bees and flies. It is important to note that not all insects have compound eyes! For any eye to be of value, it must detect light and shades of darkness, and would be better advantaged if it can detect colour, perceive 360 degree views, be self-cleaning, auto-focussing, and work as one of a pair to enable stereoscopic viewing and thus depth and distance. Since a lot of data would need to be interpreted in real-time, a lot of brain mass would need to be dedicated towards this single task. Although mammals, with their greater size than insects, have sufficient 'processing' capacity to accommodate a complex eye, the insects do not not. This has led to a uniquely different approach by evolution to design an eye which needs minimum processing capability to be useful: the compound eye. Compound Eye The compound eye of both a fly and a bee is constructed of hundreds of tiny simple lenses called ommatidia wiki (individual "eye units"). Insect Compound eyes can typically consist of between 2 and 30,000 individual units. Each unit can perceive a tiny part of the external world, like a piece in a mosaic. All the image chunks are combined within the insect brain to form a complete image, albeit - an incomplete one due to the divisionary walls around each unit. We can only really speculate about what kind of image is perceived inside the insect brain (mind?), and we have no way of telling if the divisionary lines between image pieces are removed as part of the processing, or whether they are left in.

So, what would it be like to see the world through the eyes of a fly? Well, using 3d modelling and anaglyph image creation, we can probably get a fairly good idea. Let's take a look! |

||||||||