Having reached the grand old age of 80, purely by accident, I, nonetheless, feel that I can risk making pronouncements which I am sure will largely be ignored and dismissed as the rantings of a boring old curmudgeon. So onward and upward.

1) Never buy a new microscope. It’s like buying a new automobile which will lose half its value in the 2 minutes it takes you to drive it away from the dealer’s lot. Or if you have lots of money and are foolish, due to genetics, you might buy a Lamborghini for $200,000+ which will go 200 mph. But where would you be able to drive it outside of special tracks or out in the desert salt flats?

There are now many very fine used (pre-owned–what idiotic Madison Avenue marketing jargon) microscopes, but caveat emptor, (the emperor wants caviar) buy from a reputable dealer or an eBay seller with a full refund return policy. On arrival, test it thoroughly, put it through its paces to determine if there are any flaws and then decide whether or not it meets your needs.

2) Never buy a microscope with features you’ll never use, unless they happen to be included and are incidental to what you really do need and desire. For example, I have acquired 2 microscopes that have fluorescent capabilities using high-pressure mercury vapor illuminating systems. I have used them only a few times as I am quite wary of these UV systems, although I know that they can produce mesmerizing results. However, the intense heat, the relatively long wait period for the system to achieve optimal conditions, and the life of the mercury vapor bulb are discouraging factors for me. The life of the bulb has to be carefully monitored as there is the possibility of explosion causing damage to the instrument and your good self after the number of hours specified as a limit by the bulb manufacturer.

However, both of my instruments are modular and multi-functional and fluorescence microscopy was not a significant factor in my purchase of these microscopes. However, with the advent of LED UV systems, which don’t generate large amounts of heat nor have an extended wait time nor present the risk of explosion, I am once again tempted to venture into the realm of fluorescence microscopy.

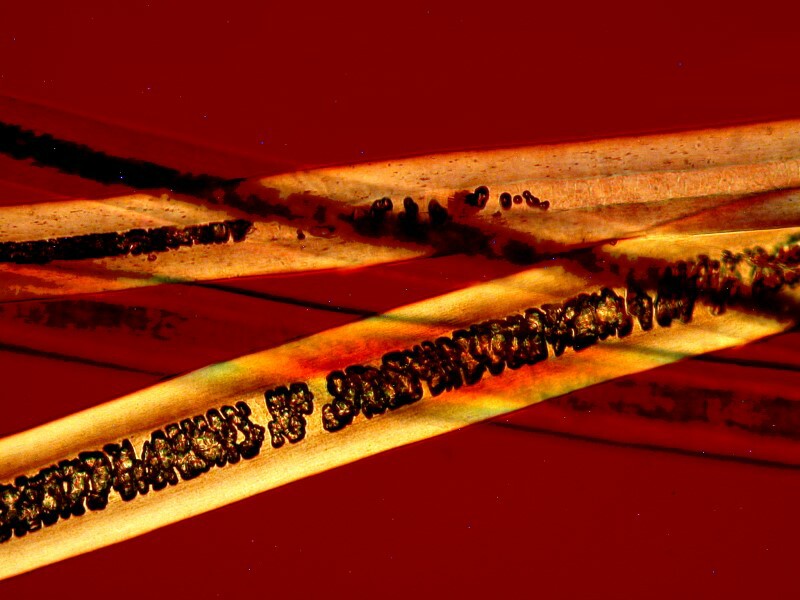

3) Buy a microscope which still has a variety of accessories available. It is always a delight to discover a new technique and even more so to find that there is an accessory that you can add on for a reasonable cost. One of the most pleasing additions is that for doing polarizing microscopy. The results are often dazzling and there is a great deal of satisfaction to be derived from exploring the various applications of this technique. In previous essays, I have presented lots of images of crystals under polarized light. However, here, I’m going to show you some other kinds of subjects that are highly interesting with polarization, starting with some sample of different kinds of hair.

This is hair from a hedgehog (not a thicket pig).

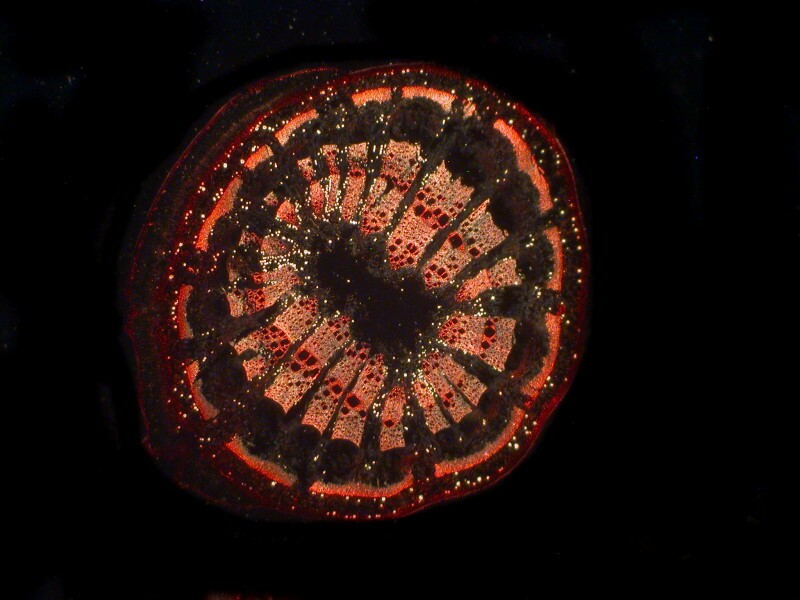

Here is a cross section of a hair from a peccary, which is much closer to being a thicket pig.

Prairie dog hair. We have lots of prairie dogs around here. Ranchers regard them as pests. However, they are quite interesting in that they form communities and when any mad microscopists come in try to steal some hair, they whistle warnings and then they all hide.

Polish rabbit hair.

Hair from a platypus. I flew all the way to Austria, waded in streams and ponds, trying to find a platypus and then someone told me that it’s Australia not Austria where they’re found. So, I came home and bought a slide on eBay.

Tiger hair. This always reminds me of a bit of doggerel from a critic who didn’t like Blake: “Tiger, tiger, my mistake! I thought that you were William Blake.”

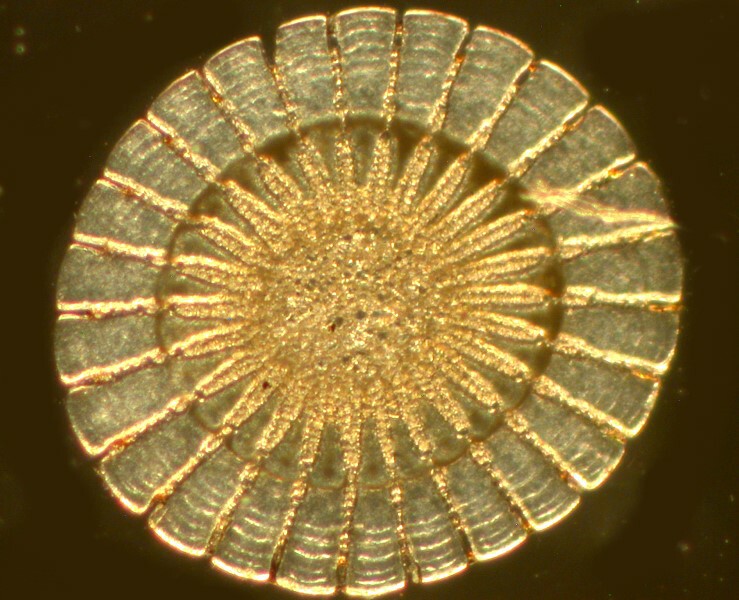

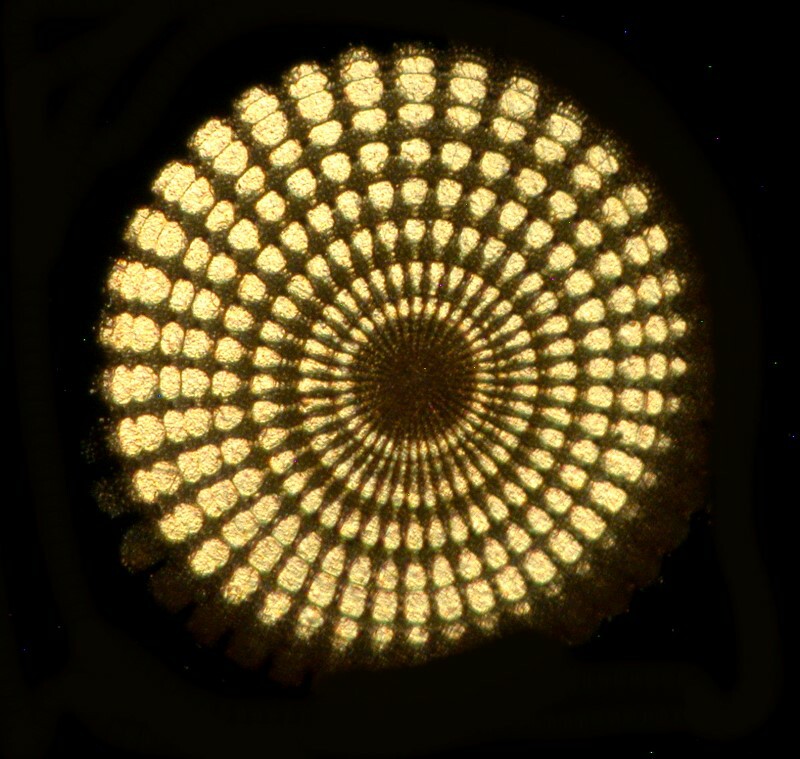

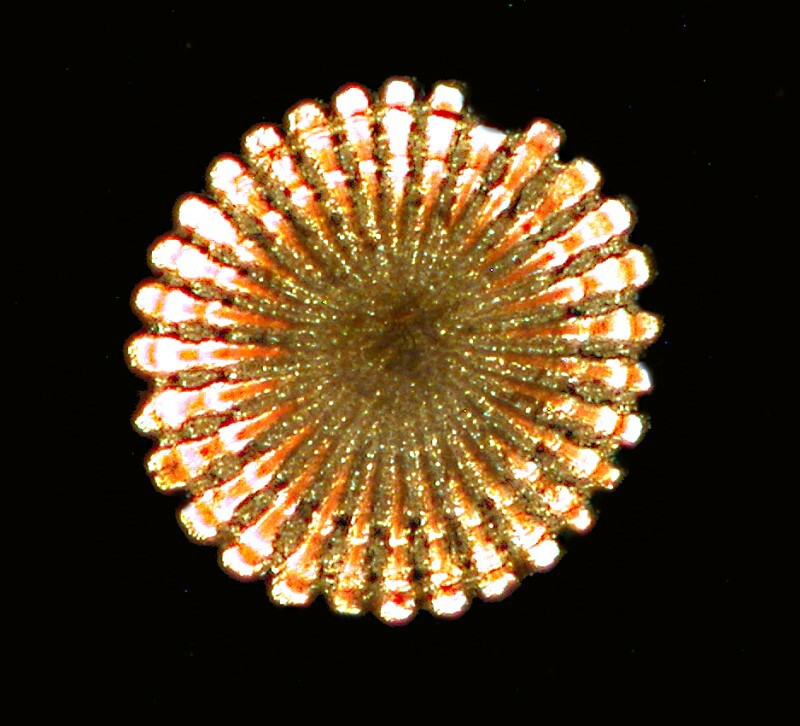

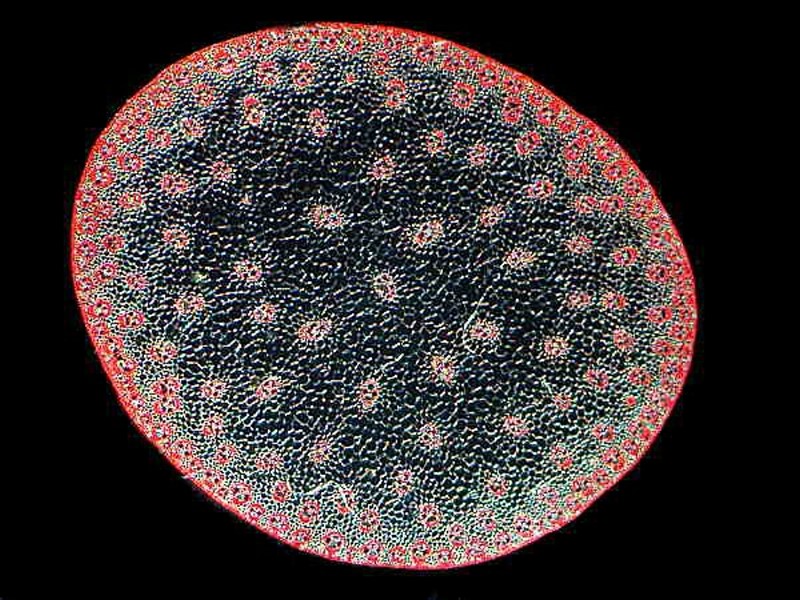

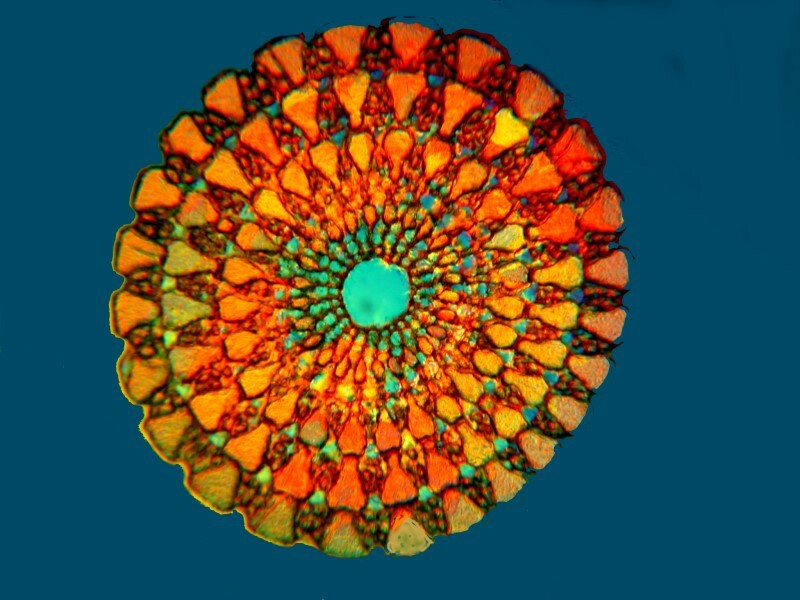

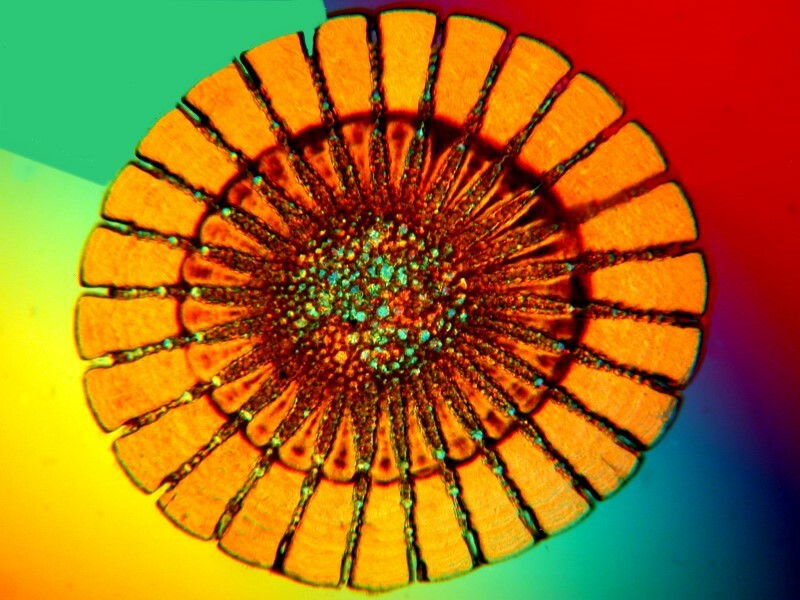

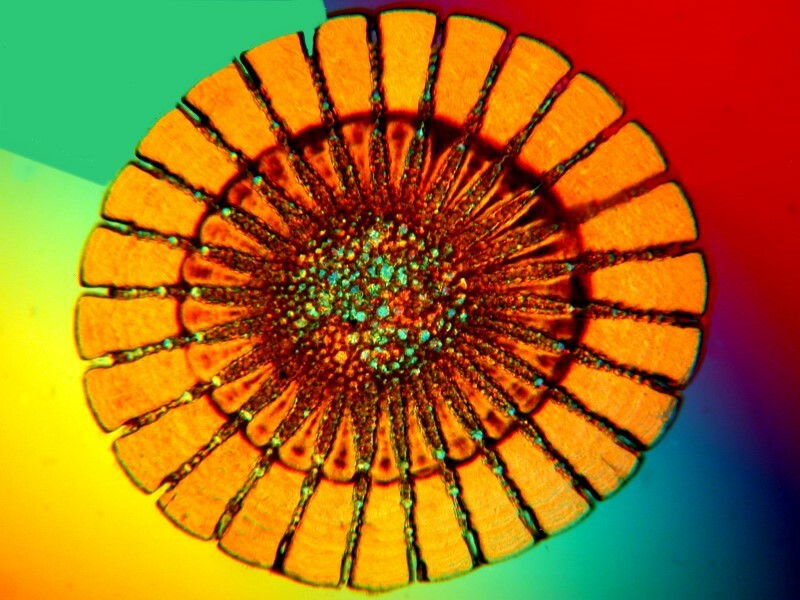

Another type of specimen that is often pleasing under polarization is cross sections of the spines of sea urchins. I will present you here with 3 examples.

Next up, some scales from ferns, not to be confused with scale insects on ferns. The former are structures of certain types of ferns and can be spectacular under polarized light. For more information on these structures, see Brian Darnton’s article.

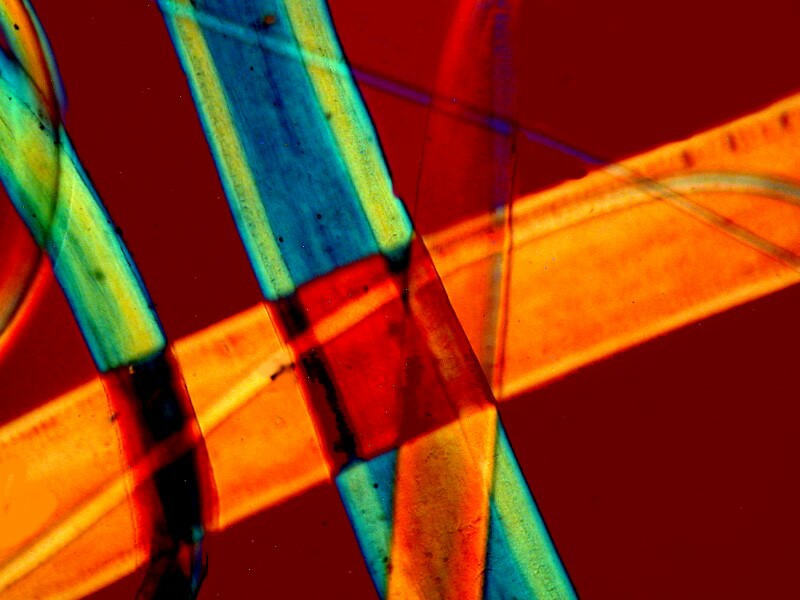

Let’s shift gears once again and look at some cross sections of plants. Many botanical sections are stained in order to differentiate structure and detail. In some instances, the stains themselves react to polarized light and further enhance the image.

This is a section of the stem of Aristolochia or “Dutchman’s Pipe” It is a striking looking plant as you can see here.

It is a known carcinogen and toxic to the kidneys as well.

Here are 2 images of a cross section of a citrus (type unspecified) stem. The first is brightfield and the second polarized.

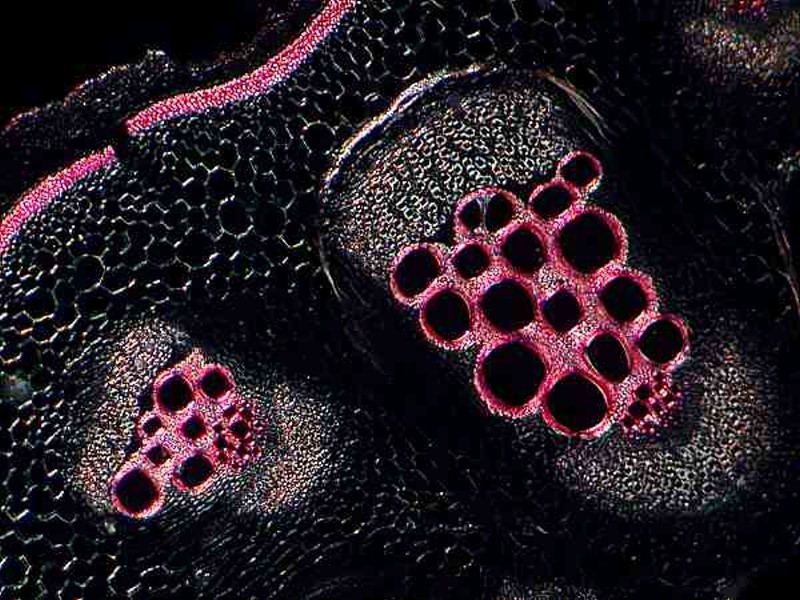

This is a cross section of the stem of a corn plant. If you look carefully in the inner part, you can see bundles of tubules which transport water and minerals up to the ear so that you can get the nice juicy kernels that you love to eat.

This is a section from an unidentified plant, but it is instructive in that it provides us with a vivid view of the tubules.

If you’re lucky, you may find a Nomarski DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) system at a reasonable price. This is a brilliant technique which can produce stunning result with the right specimens and skillful adjustment. Nomarski allows for “optical staining” and “optical sections.” This latter works with relatively thin specimens and permits one, with a slight change of focus, to move down through the “layers” of the specimen. Furthermore, by adjusting the prism one can alter the colors of the image and when carefully adjusted achieve superb contrast.

I’ll show you some examples here. This first one is an image of the anchors and plates from the sea cucumber Synapta sp. which have long had an appeal to microscopists who do special mounts.

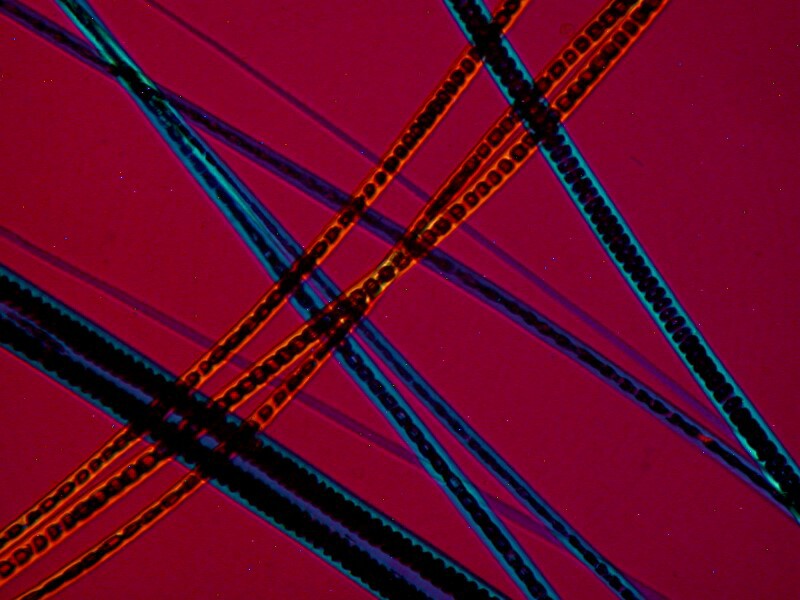

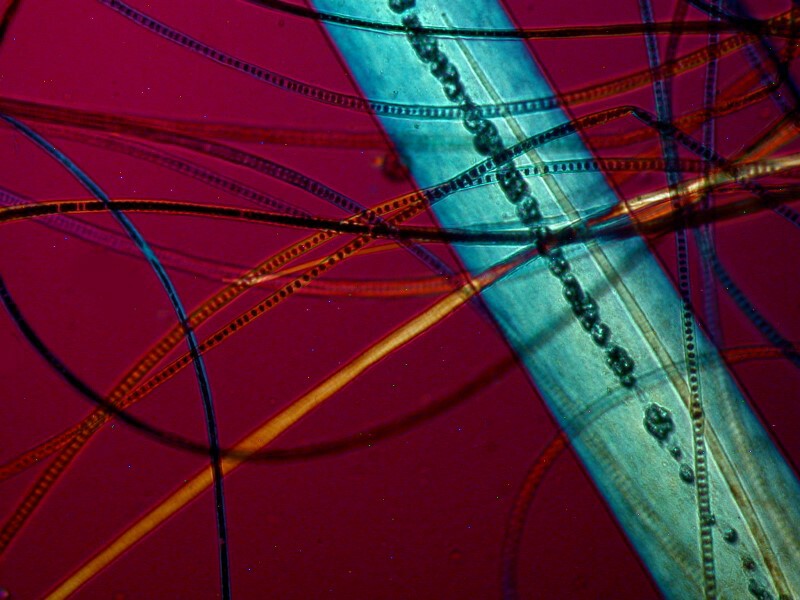

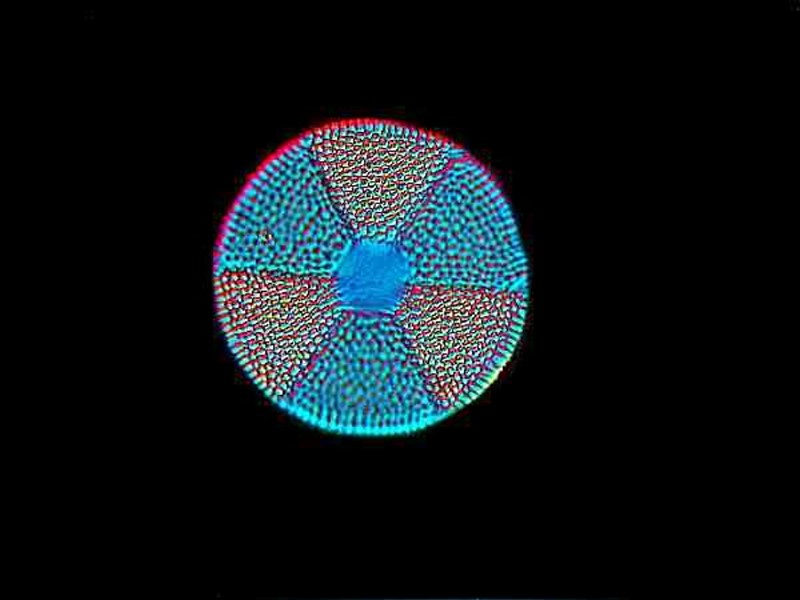

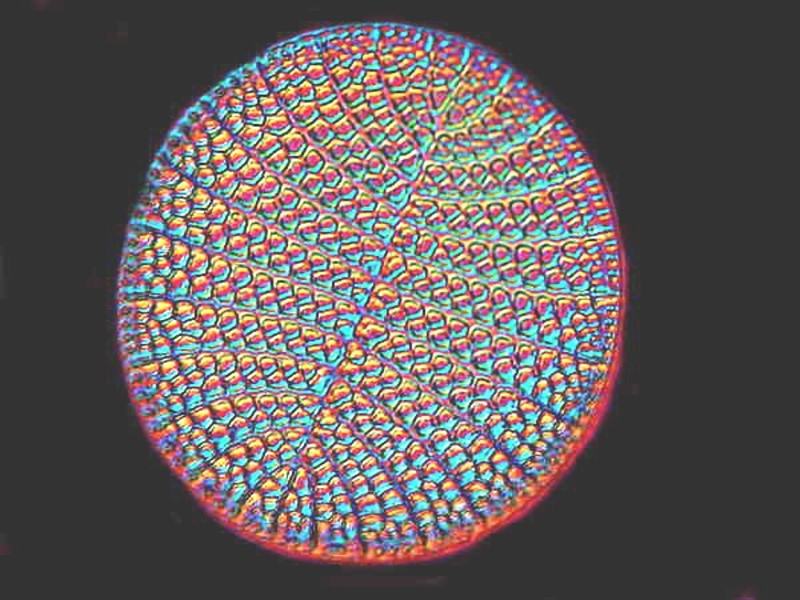

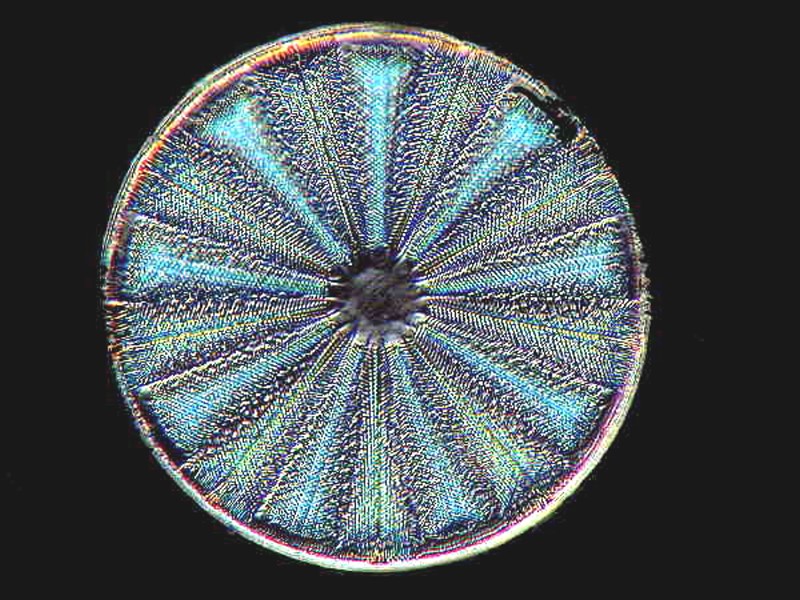

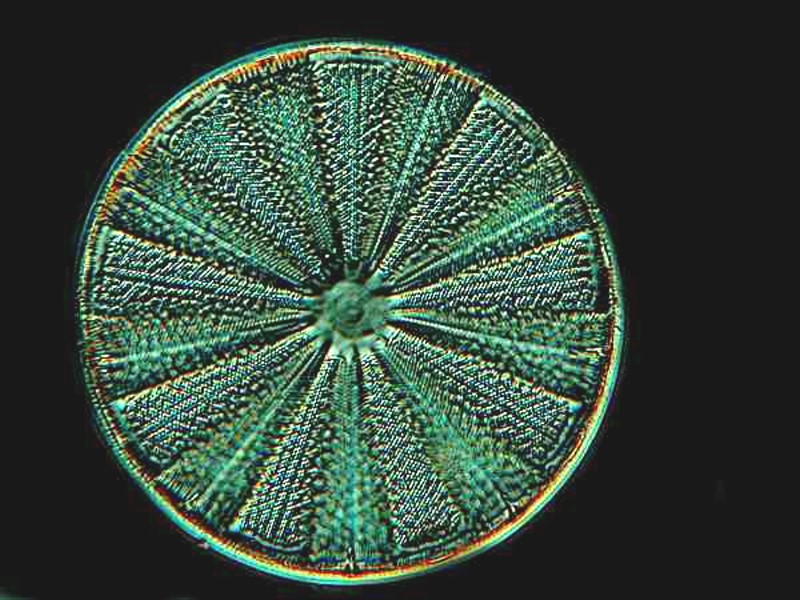

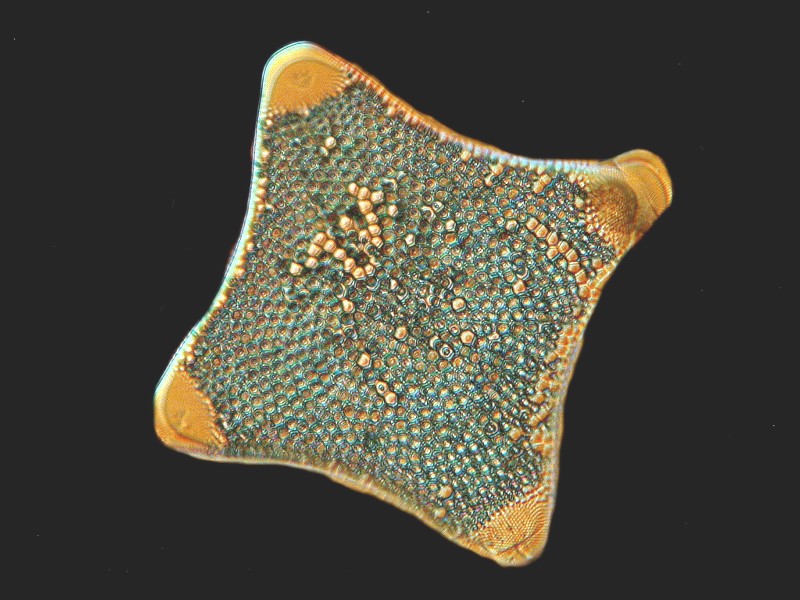

Diatoms also fare well with Rheinberg illumination as the following examples demonstrate.

However, since even used DIC systems are not inexpensive, you might want to experiment using colored filters to explore Rheinberg illumination. There are several good articles on this technique on Micscape, so I’ll limit myself to just showing you a few images using color filters and Rheinberg.

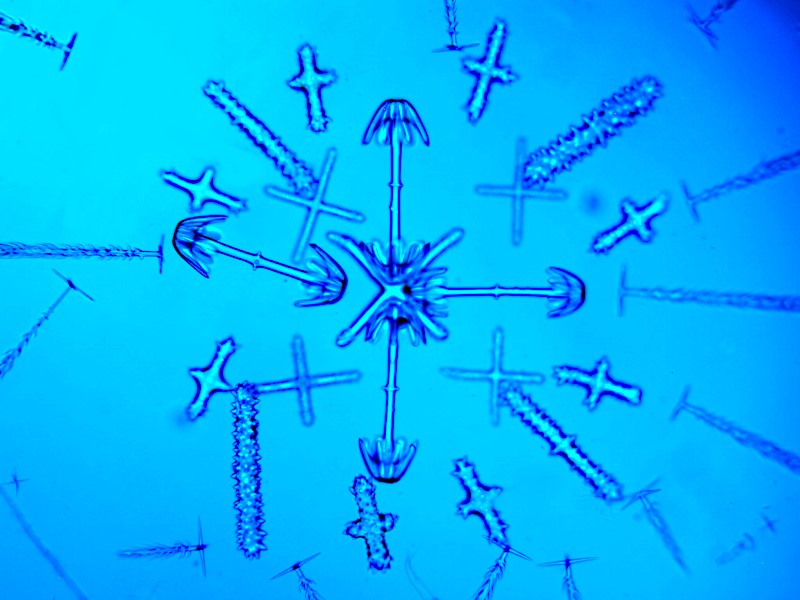

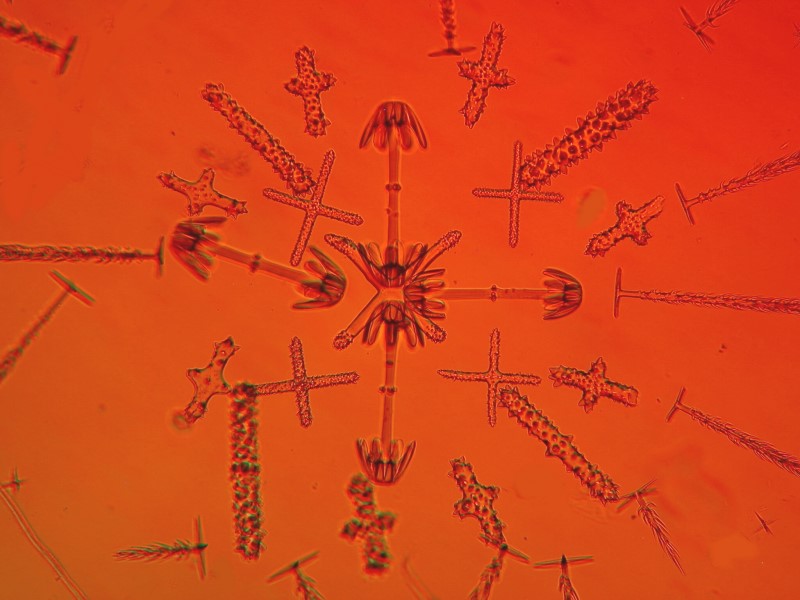

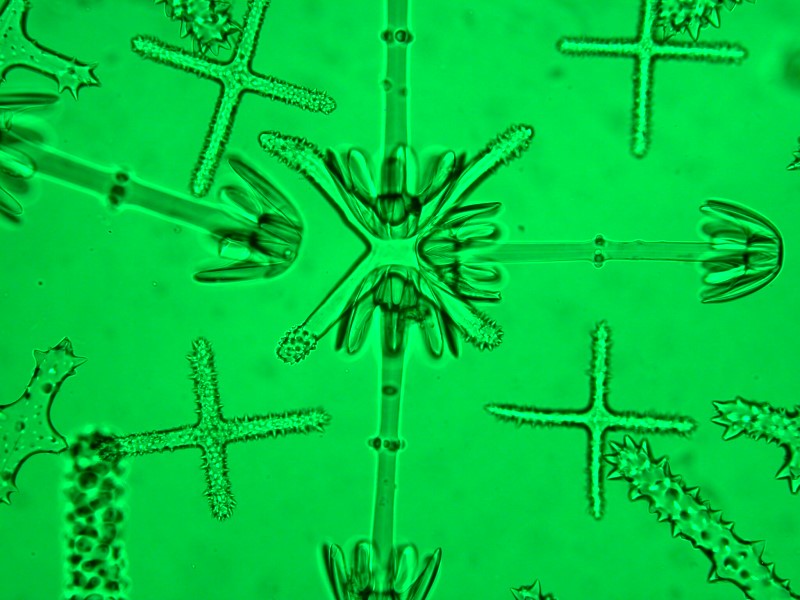

Another object of special interest to 19th Century mounters as well as recent ones are the spicules of certain glass sponges. Hyalonema is a prized species because of the variety of intricate, complex and beautiful spicules. Photographing them can be a challenge because, remember, you are using glass oculars, glass objectives, glass condenser lenses to photograph objects which are essentially glass. I will give you three filter backgrounds, blue, red, and green. To me the green is the most satisfactory.

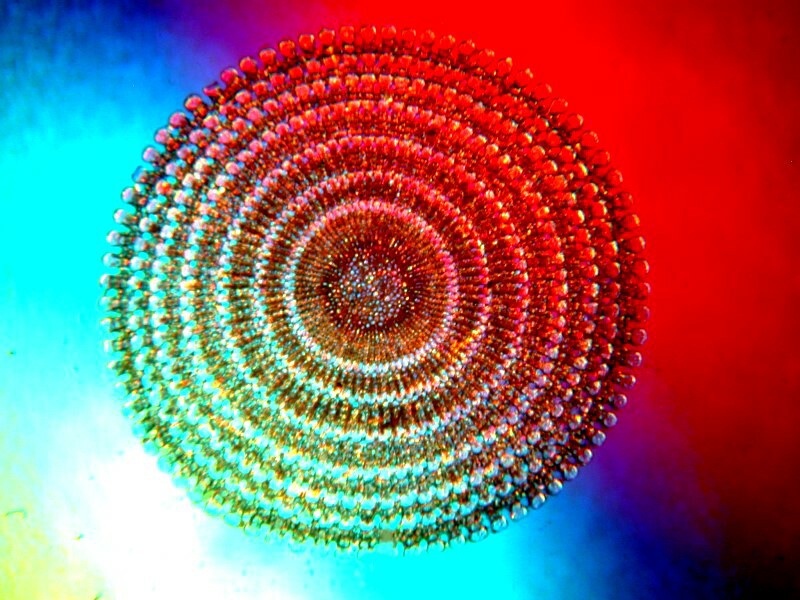

Yes another favorite is the cross section of sea urchin spines and I’ll show you 3 examples here.

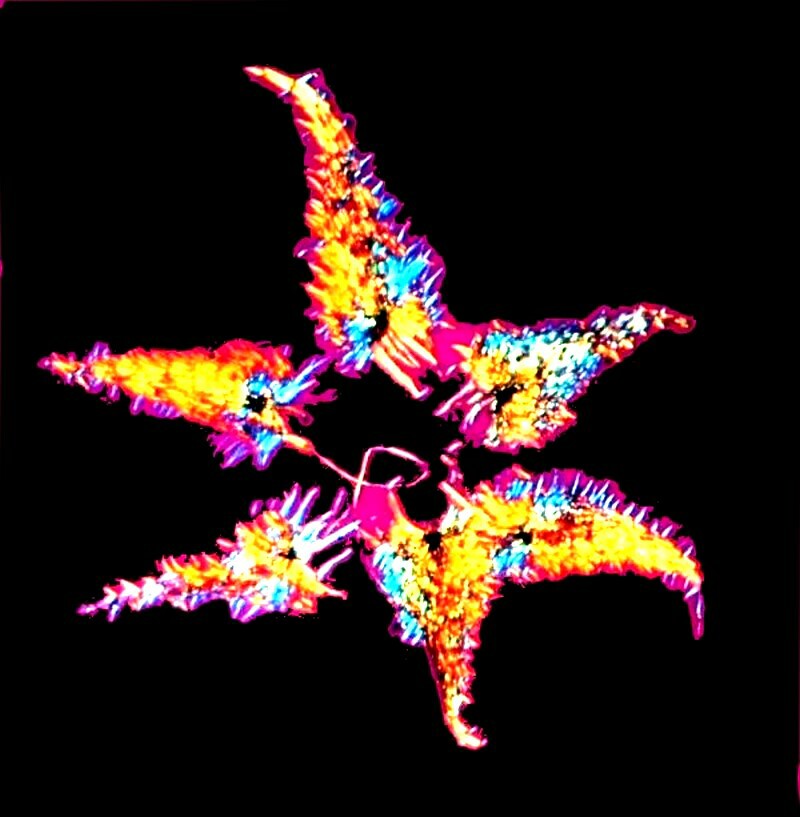

And finally, a radula of a chiton. These are fascinating objects and can also be a challenge to photograph. Rheinberg illumination provides some interesting opportunities.

4) Never buy a microscope from a used car salesman or a used car from a microscope salesman.

5) Keep dust covers on your microscopes. However, it’s advisable to remove them when you want to use them; it makes observation considerably easier.

6) Do NOT use sandpaper, steel wool, Vodka or any form of alcohol, Windex, or other popular cleaners on your microscope lenses. The debate over what one should or shouldn’t use has a long and complex history. Several firms supply commercial cleaning products for cleaning microscopes and generally these are safe, if not ideal, but inform yourself about the pros and cons of various cleaners.

7) If you are daft or misinformed enough to venture into lubricating rack and pinion focus or condenser mechanisms, do not use oil, Vaseline, WD40, or chocolate syrup. There are special greases of various viscosities that can be obtained and are very good for such an adventure.

8) Over the years one is likely to accumulate a wide variety and a large quantity of specimens. Now, in the process of moving to a much smaller house, I am faced with the prospect of sorting and transporting everything from vials of micro-algae to small preserved specimens of skates, rays, and hammerhead sharks) and I strongly recommend that once a year, you reserve at least a full day to sort through your collections and decide what you want to keep and do observation and research on. I know, I know, you will want to keep everything, which is why, in the process of moving, I am faced with making lots of painful decisions regarding that to keep and what I won’t be working on in the next year. Some things I have will be of interest only me and may, sadly, have to be discarded. However, I have found that because of poor financial support for local schools, the public school teachers are delighted to have donations of biological specimens, rocks and minerals, odd bits of equipment and apparatus, supplies, such as, pipets, microscope slides, Petri dishes, etc. Also if you happen to have an older microscope which you are not using, but still in good condition, then donate it to a teacher who will set up a student essay competition for the best essays to be sent to Micscape with the grand prize being the microscope; second and third prizes, some prepared slides, a sea urchin test, a nice starfish or shell–whatever is readily available.

9) Have a garage (yard) sale at least once a year!!! This provides the opportunity to go through your collections and decide which items you’re not like to examine or make use of in the next year. For example, you might well decide that the stuffed Hippopotamus is no longer crucial to your research. Many of us have a tendency to be rather passionately, comprehensive collectors, only to later discover that we have acquired items that we simply cannot find time to properly investigate in a finite lifetime.

When culling ones collections is an excellent time to organize what remains to make it more readily accessible.

11) Another sin of those of us who are enthusiasts is the accumulations of bits and pieces of apparatus, accessories, and those essential little etceteras, like lens caps, plastic cases for objectives, and plugs for unused phototubes. I have a small drawer of odds and ends of objectives and eyepieces. I found a couple of objectives for brands of microscopes I no longer have. The same for some oculars. So, I gave them away to some younger fellow enthusiasts who, it is likely, will in 20 years be looking for someone else to give them to.

There is a small plastic cabinet with 12 drawers; one drawer is filled with small screws for various microscopes and accessories, another filled with tiny springs, yet another with washers–well, you get the idea. And we all know that the next day after I get rid of this stuff, I will find that there was something there that I needed. So, what happens?–I keep it for another 10 years.

Nevertheless, I strongly recommend an annual review to attempt to reduce the number of things that you really in all honesty don’t need. My strongest motivation for reducing my stock of items is the pleasure which it brings to the recipients. How much better it is for these items to sit on some else’s shelves with a real possibility that they will be put to a productive use rather than moldering unused on my shelves.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the July 2019 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .