In Part 1, we mentioned some of the different sorts of material used to mount specimens: materials such as bone, wood, tortoise shell, and ivory. We also considered some of the types of specimens that were considered highly desirable in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. However, in this part, I want to focus primarily on papered slides. Gradually, a sort of standard for the size of slides emerged (1" x 3" or 25mm x 75mm), but the Victorian enthusiasm for the unusual persisted and there were notable exceptions. Petrographic slides containing sections of rocks were frequently smaller and many still are today. Some types of slides were larger and even square rather than the usual 1 x 3 rectangle. I recall recently seeing a slide for sale on the Internet which looked to be 3 or 4 inch square containing a large section of a human embryo.

In well-to-do Victorian households, the passion for natural history was often expected to extend to the entire family and, indeed, special miniature slides were produced for elegant ladies and their children. One French mounter and his family company, the Bourgogne family, produced many such slides which were colorful and contained interesting subjects.

As you can see these, charming little slides are papered in a subtle, but pleasant fashion.

The demand for fine slides became such that a number of major mounters had to create workshops or institutes, rather in the fashion of some of the great painters. All of which is to say that if you buy a Möller slide with the distinctive labeling of the “Institut für Mikroskopie,” you cannot be certain that Möller himself made the slide; it may well have been one of his protégés or apprentices. This applies to most of the larger suppliers. Brian Bracegirdle in his superb book, Microscopical Mounts and Mounters, relates that Möller’s brothers helped him in some of his most ambitious projects such as a diatom plate for the Emperor of Brazil containing 1715 diatoms! Bracegirdle adds “...his most famous plate, the Universum Diatomacearum Möllerianum, contained 4026 species in a space of 6 mm by 6.7 mm; it took forty days just to place the diatoms.” (P. 68) The fact that the chief mounter did not himself make a particular slide, however, in no way meant that you were getting an inferior product. These makers were fiercely proud of their reputations and were well aware that they were competing with other highly skilled microscopists. In order to ensure that their wares were identifiable and readily recognizable, some mounters began using special labels and special papers which became their hallmark. However, where there is commercial demand, supply inevitably appears. Printers began providing slide papers, some very plain, some of considerable elegance, and some nearly identical to those employed by highly regarded mounters and companies. Gradually, there was a shift to just using the glass slide and usually two labels, but sometimes only a single one.

During this period at the height of fine slidemaking, the specimen areas were almost always ringed and a circular cover glass was used. Special turntables were usually employed for ringing the slides and special varnishes were acquired. Some of these were tinted and you can find slides with black rings, brown rings, white rings, and even red rings.

I’ve often wondered why, other than for aesthetic reasons, circular cover glasses were used. It seems that they would be harder to produce than square or rectangular ones and thus would be considerably more expensive, as they are today. (Perhaps, just to make my own slides more distinctive, I’ll start demanding triangular cover glasses, equilateral ones, of course.) In any case, as the biological sciences became more and more important in the curricula of high schools and universities, the demand for good, but plain and relatively inexpensive slides, increased dramatically–square cover glasses, a plain label identifying the company and the specimen became the standard. These were practical, utilitarian, instructional slides not designed for the collector. However, it should be noted that many of these slides were superior for scientific purposes to those gilded ones of the “Golden Age”. However, more about that later.

Let’s go back a bit to the issue of what’s involved in the creation of papered slides. Sometimes, cheap strips of wood were used, sometimes glass slides, sometimes just layers of heavy paper glued together–sort of a forerunner of our ubiquitous cardboard. All one really needed was a stable support for the decorative paper and the specimen. Some of the earliest papered slides were not only very plain, but frankly, rather ugly. They look rather as though someone had taken some very cheap wrapping paper of a solid color, usually, a blue, yellow, or dingy white, folded it where necessary, slapped on some wallpaper paste and punched a hole for the specimen and, in some cases, seemingly arbitrarily, near one end with no concern about centering the specimen area. Nonetheless, because of their rarity, such slides command exorbitant prices. Recently 7 slides from the 1830s (rather primitive ones to my eye) sold for $1,300 on eBay!

Collectors are one of the oddest of all species. They will sniff out some dreadful piece of kitschy porcelain which you wouldn’t have on your table or some dreary landscape which you wouldn’t hang on your wall and pay hundreds or even tens of thousands of dollars for such items and often market prices are determined much more by rarity than quality. Almost all of us have our quirky little susceptibilities, but having large amounts of money at one's disposal seems to increase them–a problem which I shall never have to confront, although I do admit to having made some eccentric purchases, but relatively modest ones. I have a very handsome copy of a book on microscopic algae–in Japanese, which I don’t read. However, it has a significant number of very nice color plates and the descriptive list with each plate gives the scientific names in Latin. So, this is not only a very nice volume, it is a useful one as well.

It seems that some collectors wish to define a certain area and possess it or, at least, corner the market. Someone decides that he wishes to own every slide ever made by the Marquis de Slide and sets about ruthlessly acquiring them. Ultimately, I think the psyche of the collector is impenetrable, although the Freudians might offer some entertaining suggestions. Or there is the obsessiveness of Sartre’s autodidact in Nausea who is reading through the public library of Bouville alphabetically. In any case, such obsessives can inflate the prices of slides and this can unfortunately extend to slides which are inferior, damaged, or have rather dull, scientifically insignificant specimen material. This means that collectors of modest means may end up purchasing lesser slides for money that would be better spent on good quality modern slides from a biological supply house.

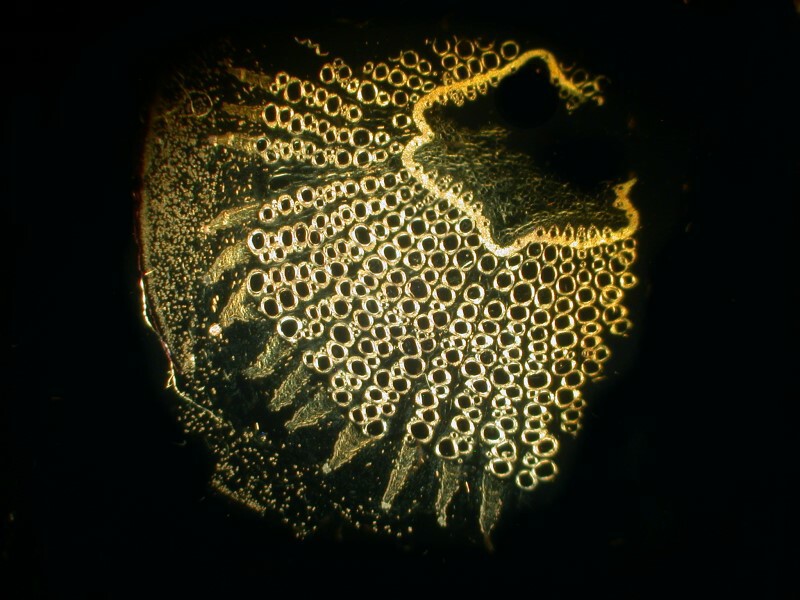

Clearly, high quality slides handsomely mounted will always be prized. Some of the Möller slides are fairly plain with simple labels, but superb specimens. I was fortunate enough to acquire a handful of them at a very reasonable price which have cross sections of sea urchin spines. I’ll show a couple of examples. First, a cardboard case of slides. Interestingly, although they all come from his institute, not two of them have the same labels.

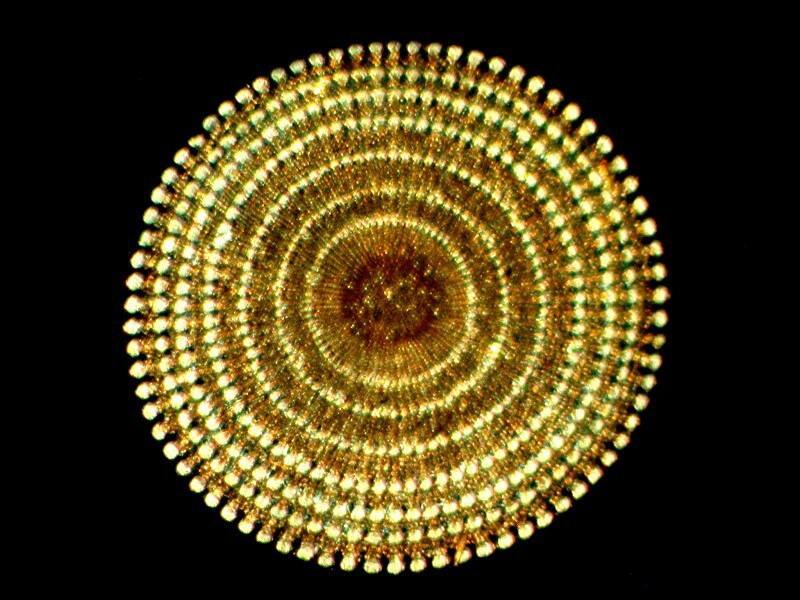

And here is an image of one of the spine sections.

Image of spine section

As you can see, the slide itself is by no means ornate, but the specimen is splendid.

For those of you inclined toward the more elegant style of slide covering, there are many fine examples. I’ll show you a few–I have only a few and most of those were given to me by friends or colleagues–however, they will give you a general idea of the classic Victorian papered slide.

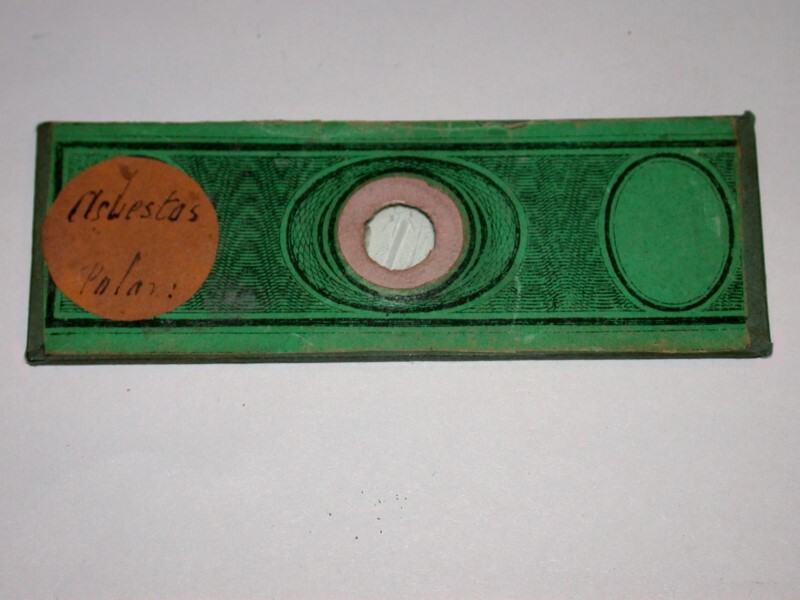

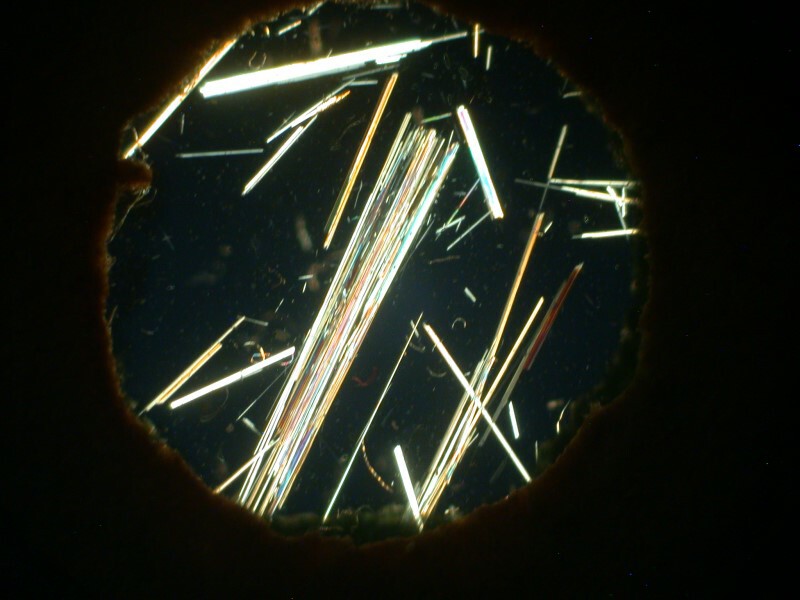

Green papers of differing designs were especially prevalent. Some of them have gilt in the design. This one is of asbestos fibers which I’ll also show to you.

Red was also used fairly often and became a common color for certain mounters, such as, Topping.

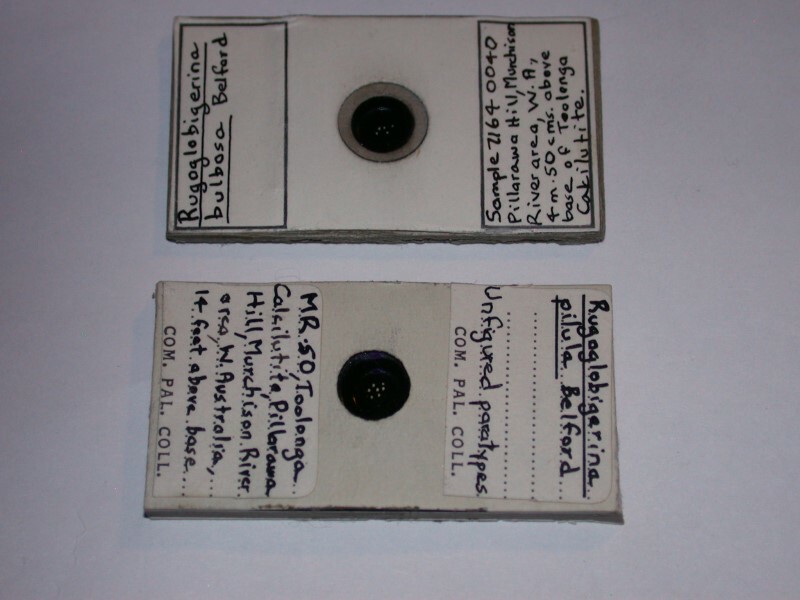

Sometimes mounters tried rather odd methods. Below are 2 small cardboard slides which were used, in this case, to mount forams and provide extensive labeling.

However, even stranger, is a standard glass slide with a piece of what appears to be double-sided tape on it which was used to mount specimens of the foram Globigerina calida. How do I know that? Well, whoever made this slide used a diamond (or carbide) point to inscribe G. calida in the glass. With some mounters, the handwriting on labels is extremely difficult to read; with inscriptions into the glass, it often becomes impossible.

I don’t know whether this slide ever had a cover glass, but it is, in any case, a disaster. Whatever foram specimens were placed on it are no longer there and only a few crushed fragments remain.

Earlier, I mentioned bone sliders and some years ago, I was fortunate enough to acquire one which is certainly not distinguished, but it is respectable. There are no mica covers and so, no brass ring to hold covers into the cells. This makes me think that this is a fairly early slider (or perhaps, just a rather amateurish one), since the specimens were simply held in the cells by some kind of adhesive resin. As you can see in the image below, the center cell has no specimen, but vestiges of some kind of mountant remain.

I’ll show you closeups of the four cells with specimens:

1) Fragments of the elytra of a beetle

2) Two parts of the elytra of a beetle and a leg in the center

3) A bit of silvery metallic ore which could be silver

4) On the left, a fragment of what could be calcite and, on the right what is apparently a crystalline form.

At one time, such sliders were produced in some number and were quite in demand, but gradually fell out of favor until modern collectors decided that they were good investments.

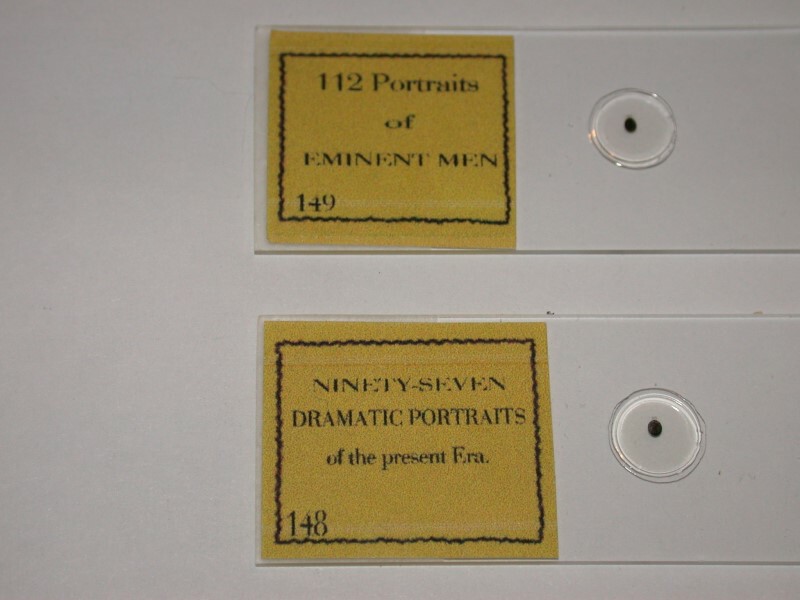

Another passion which some mounters and collectors developed was an obsession with micro-photographs which used photo-reduction to produce a photographic image which has a tiny dot that could be mounted on a slide with plenty of room to spare.

These two contain A) 97 Dramatic Portraits and B) 112 Portraits of Eminent Men. (Both state on the label “after J.B. Dancer.)

Personally, I find this particular obsession rather peculiar and tedious with a few exceptions. I can’t imagine anyone sitting down at a microscope with these 2 slides and attempting to identify all of the personages on them. Years ago, an acquaintance gave me a 2 inch by 2 inch plastic slide containing the entire King James’ version of the Bible with both Old and New Testaments. It is billed as “The World’s Smallest Bible”. No, even if I were religiously devout or devoutly religious or even mildly fanatical, I still wouldn’t have the slightest inclination to read it (or for that matter, any other book) through a compound microscope.

I mentioned that there might be exceptions and I’ll give you 2 examples. In the last 2 or 3 years, on eBay, some sets of slides of erotica (female nudes–probably about 100 years old–the slides, not the females) I am sure found a ready market. For these days of the Internet, they seem quite tame and almost charmingly innocent.

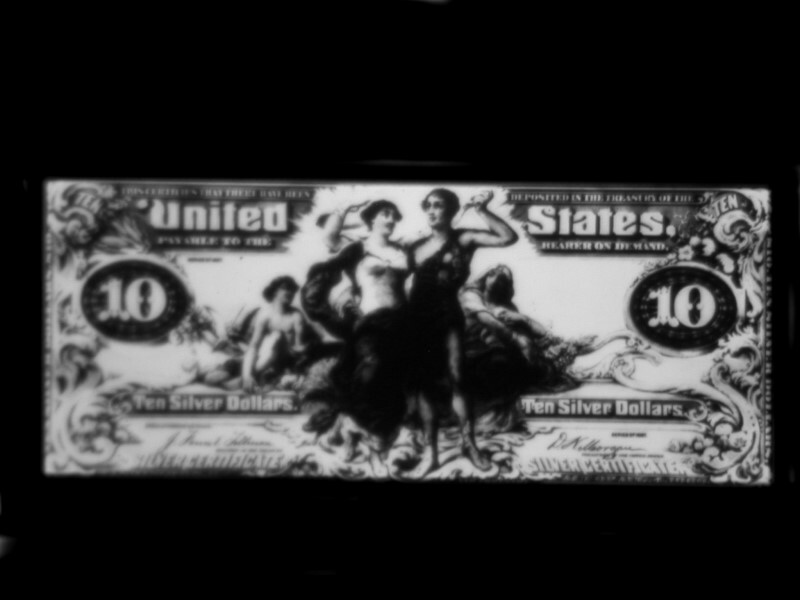

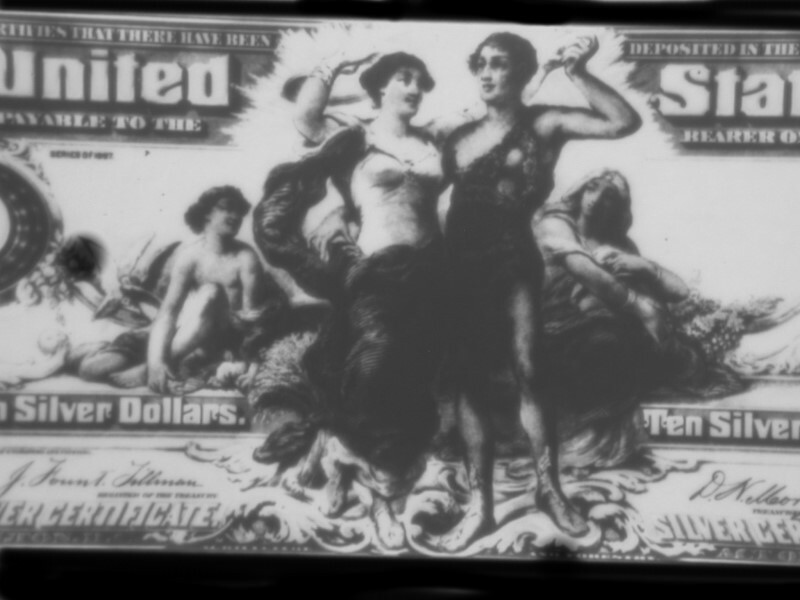

The other type of exception is related to a slide which I happened to acquire and which I suspect is a reproduction of a Dancer slide as are the other 2 which I showed you above. This one is a micro-photograph of an 1896 United State $10 silver certificate. I’ll first show you the whole bill and then a closeup of the figures in the center.

When I first looked closely at this, I thought, “O.K. This is a joke: a put-on.” Given the moralistic attitude of ordinary Americans at the time buttressed by a long tradition of Puritan hypocrisy, such currency wouldn’t even fall into the category of Erotica. In 1893, four muralists had been selected by the Bureau of Printing and Engraving to introduce “Art” to Americans through their currency. There is an interesting essay on the history of this matter which can be found at http://flyingmoose.org/truthfic/1896.htm There is a magnified image of the $10 bill that we have been looking at and we are informed that the two figures represent Agriculture and Forestry, although I can’t determine which is which. To me it would look more like a “Me, Tarzan, You, Jane” image were it not for the fact that the male looks rather androgynous with webbed feet. As it happens, this bill was never released because the bankers opposed it. Some things don’t change.

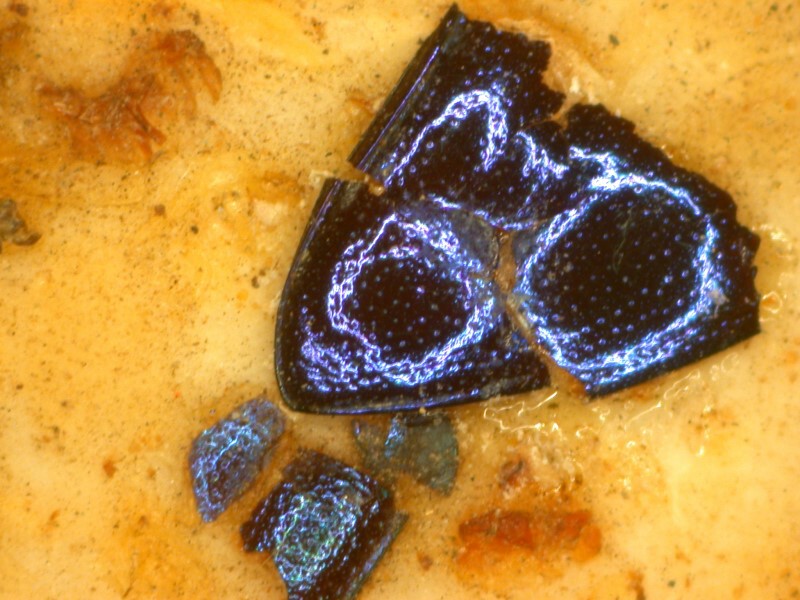

Finally, I want to raise 2 issues regarding technique in slide making. Dry mounts of certain kinds of specimens have been popular and some of them are indeed splendid. However, there can be difficulties even for professional mounters. I have long been intrigued by moth and butterfly eggs (although usually it’s the empty casing that one finds) and, over the years, managed to acquire 3 slides, the most recent one done by Watson and from a macro viewpoint it looks to be a very nice slide, nicely done.

However, a closeup on the eggs reveals a significant problem; the entire inner area of the cell is overgrown with mold and the hyphae are so dense as to make the slide useless.

It might be possible to remove the ring and cover glass and salvage the egg casings, but they are quite fragile and it would involve a fair amount of rather delicate work and, of course, in the end, it would no longer be a Watson slide. It may have been that the slide was not adequately sealed, but mold spores are notoriously resistant and ubiquitous. Perhaps, a tiny crystal of thymol or camphor or some other chemical could have stopped the mold from growing or perhaps a fluid mount could have been used but, in any case, this slide is a loss.

The other difficulty which I want to mention is sloppy microtomy. I have a small box of botanical sections prepared by an amateur enthusiast. They certainly aren’t hopeless, but they are seriously incomplete as preparations intended to provide significant information. The section has been done in such a way as to provide only fragments of a good cross section. They are not uninteresting but, they certainly are fragmentary and my objection is not merely aesthetic, but an informational one which is a result of poor or indifferent technique.

The first slide is a section from Semele sp. which is native to the Canary Islands and Madeira. Unfortunately, we get only a part of the outer edge and thus have no access to the central part of the stem.

I’ll show you 2 views, first brightfield and then with polarization.

The second slide is a fragment of a section of Vitis sp. a grapevine. Again, brightfield followed by polarization.

This fragment is provocative and again, too much is missing–we can’t see the elves mashing the juice with their feet. Ah, well, my own adventures with microtomy have not been distinguished, so perhaps, it’s best to end this essay.

Unfortunately, older slides such as we have been looking at throughout this essay, in good condition, are becoming more and more difficult to obtain and are becoming more costly as well. In Part 3 of this article, I shall talk about how one can go about making one’s own papered slides.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the July 2015 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .