|

|

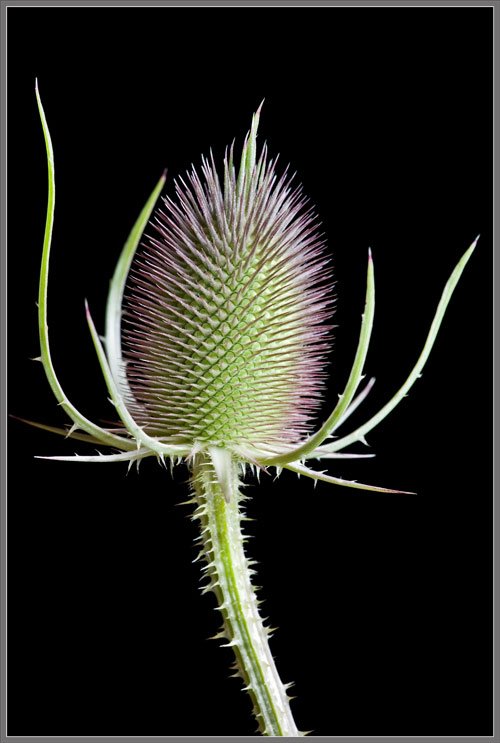

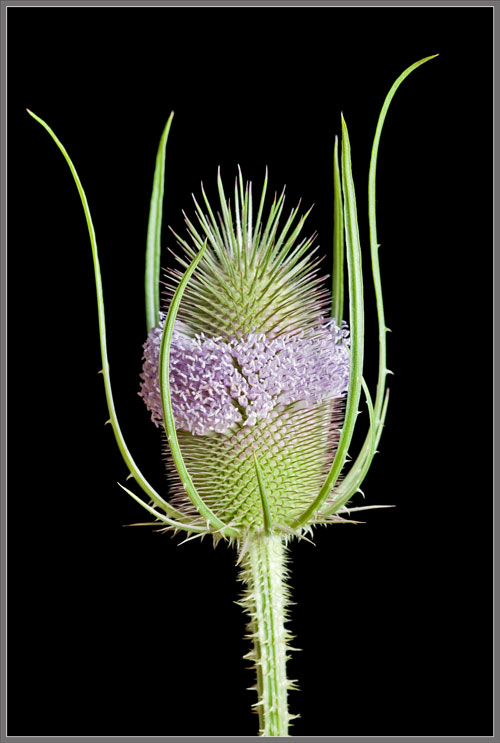

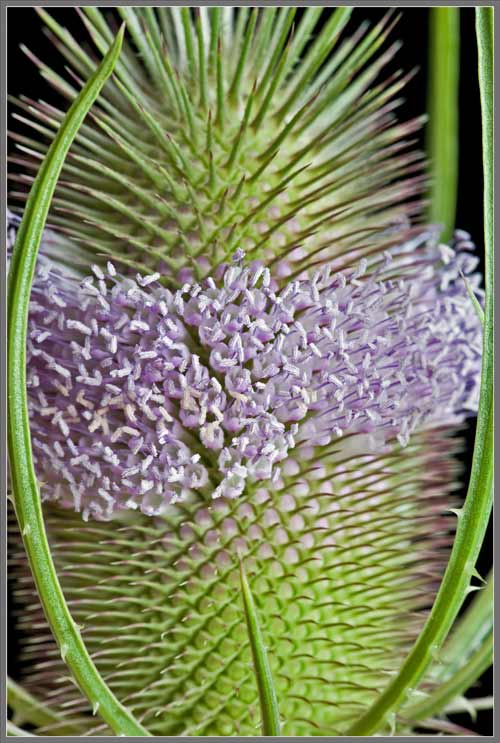

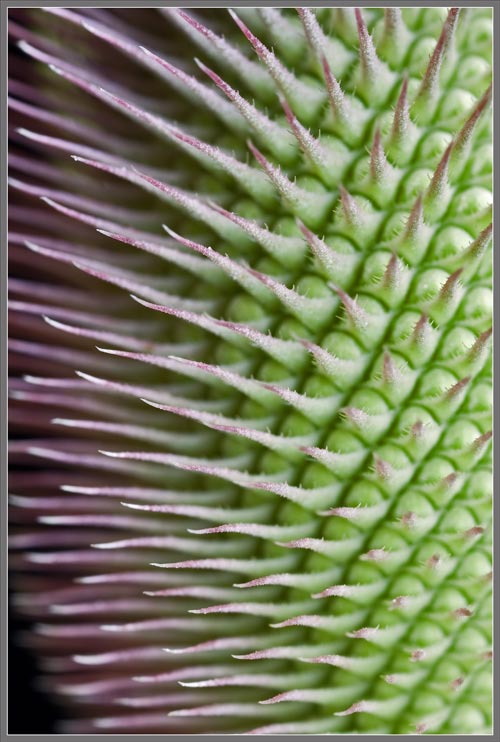

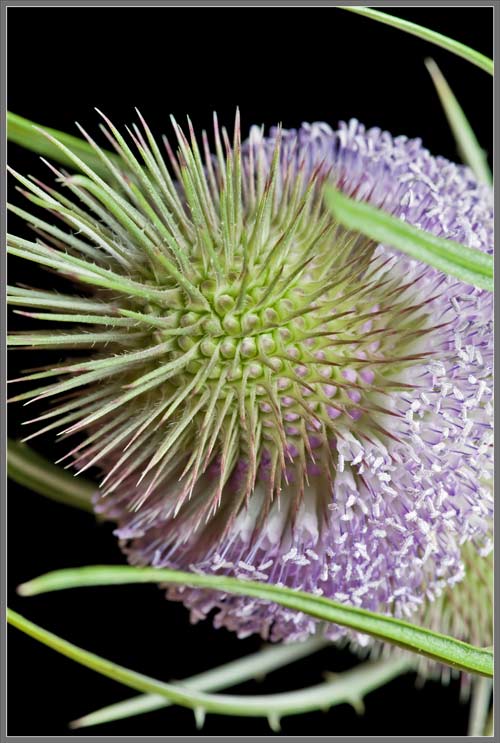

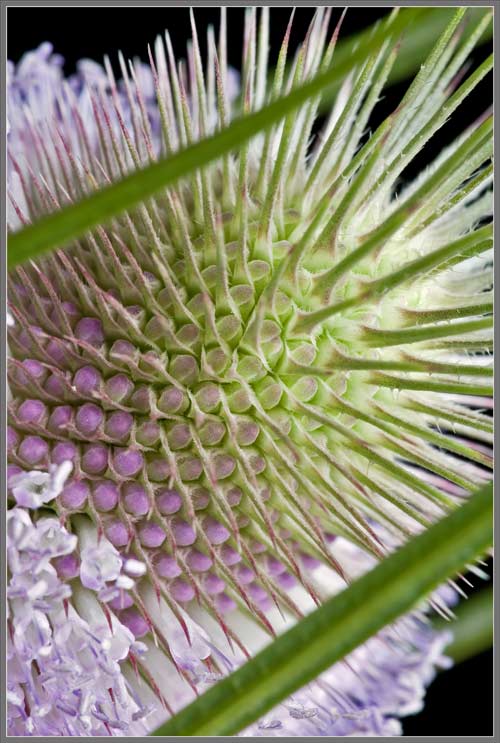

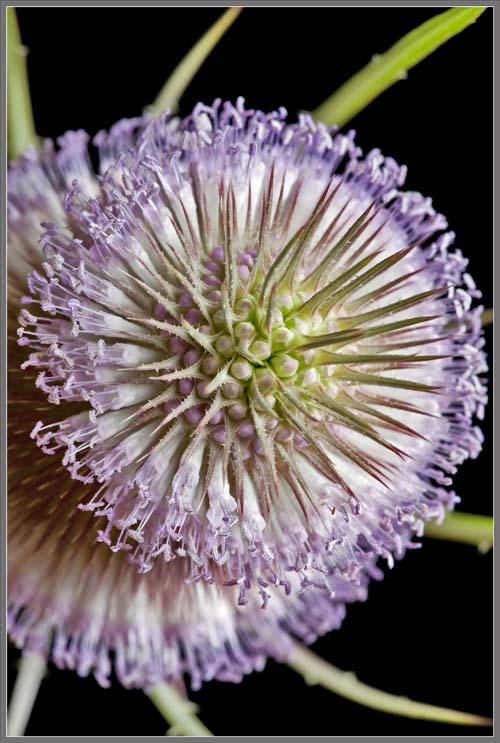

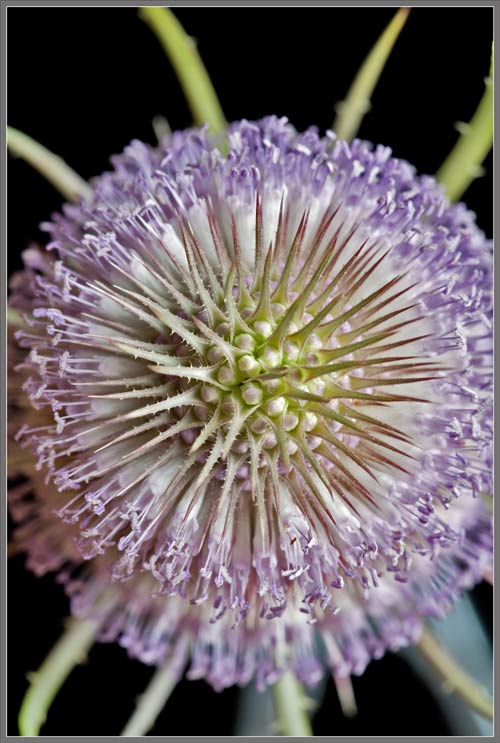

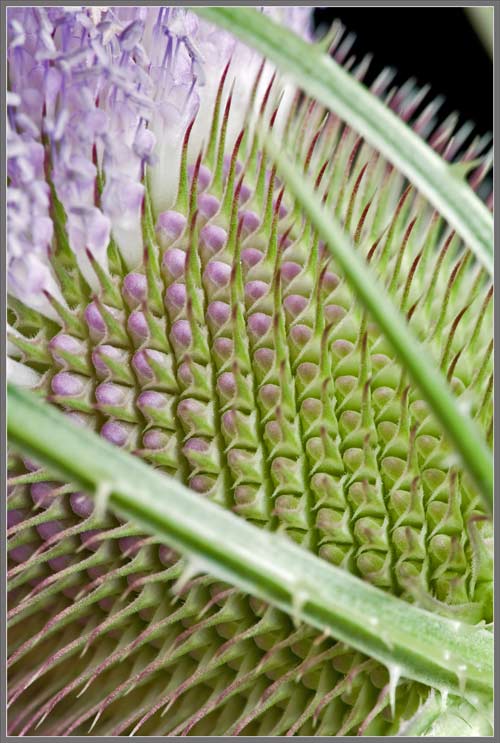

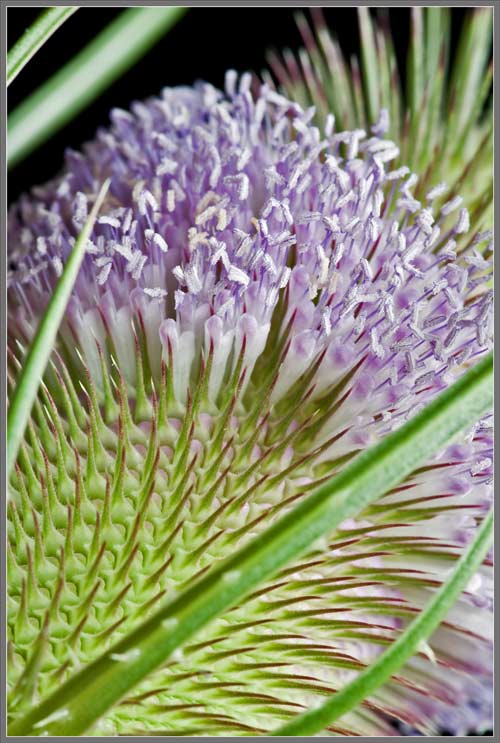

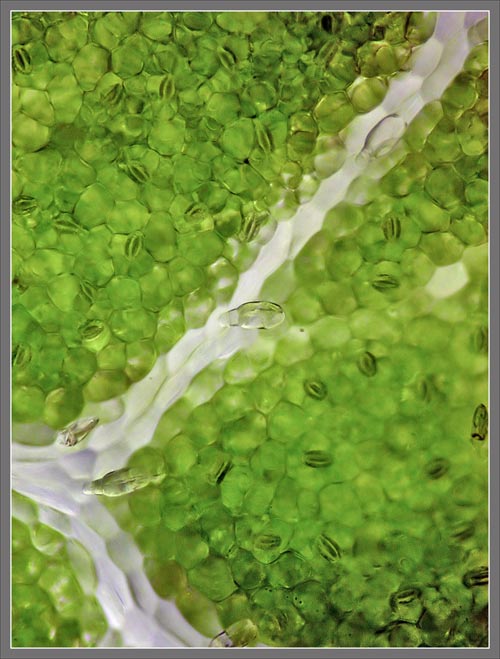

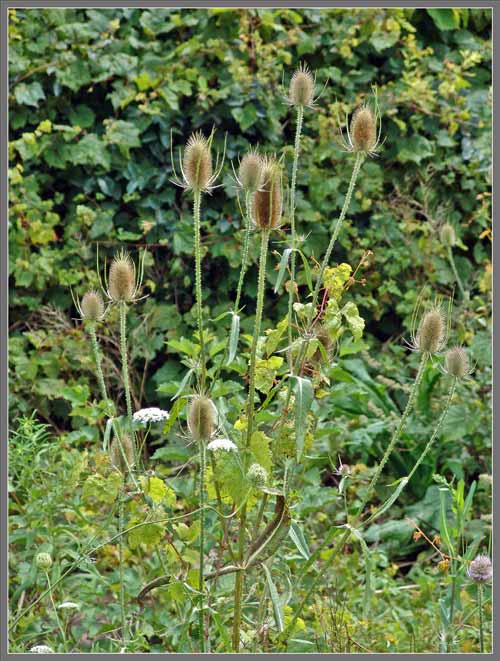

A

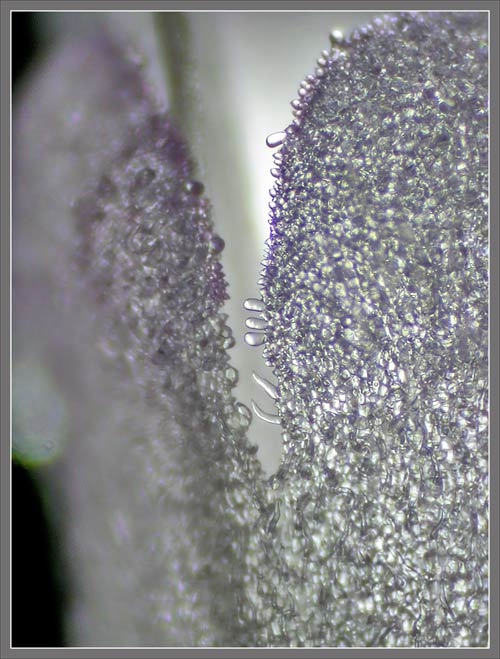

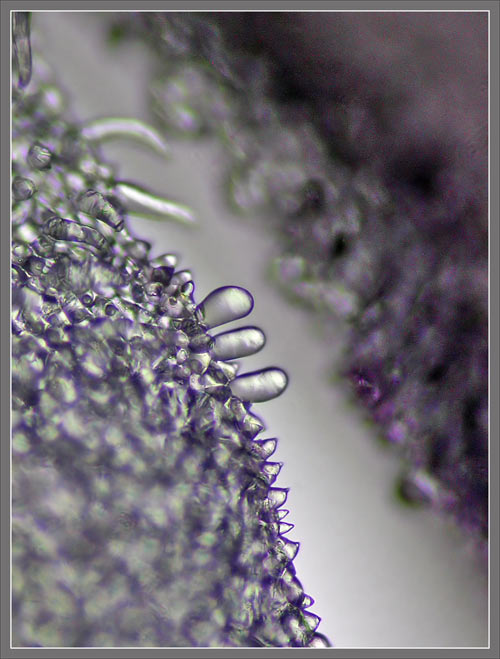

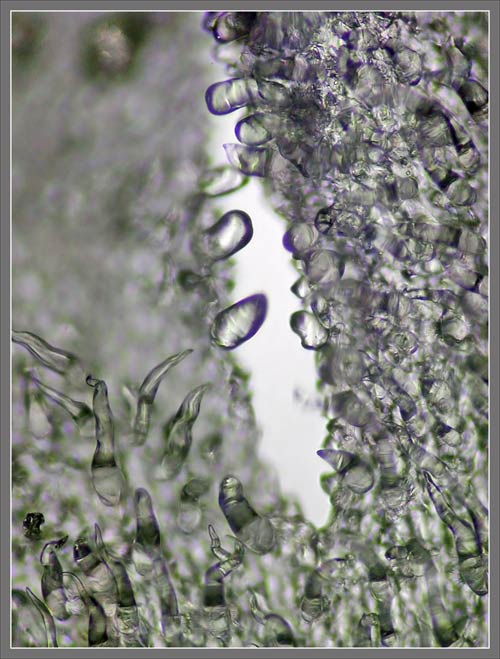

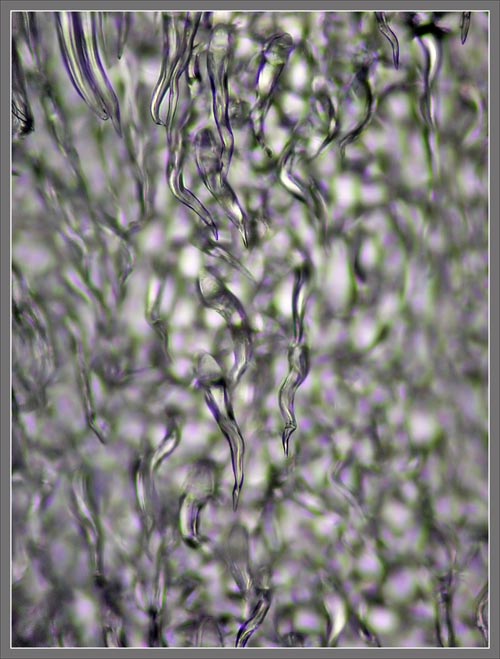

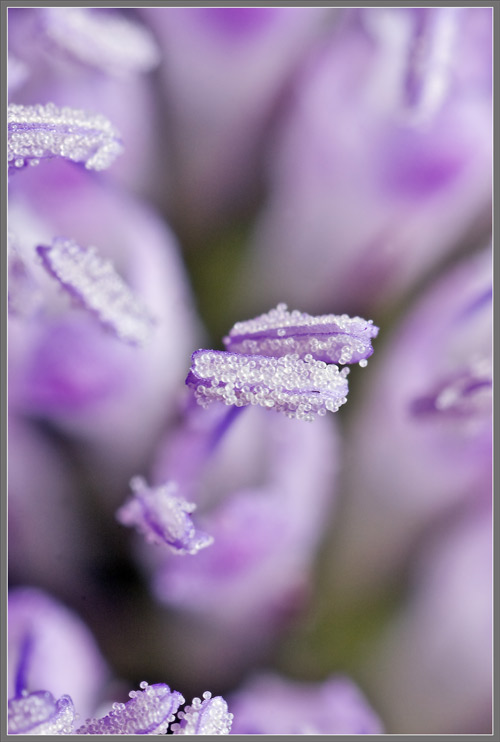

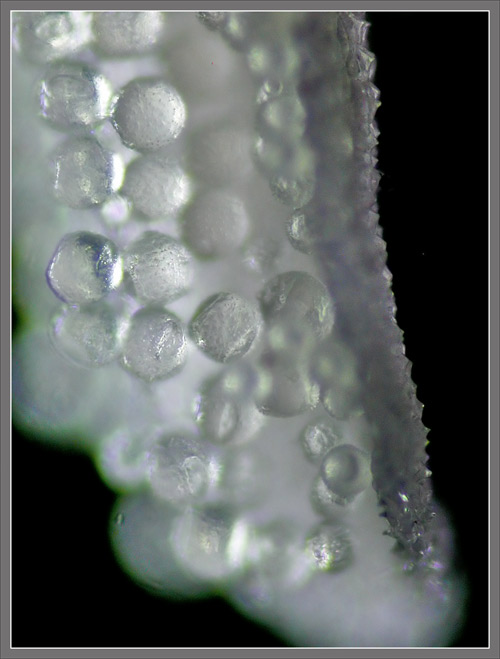

(Second) Close-up View of the

Teasel

|

|

|

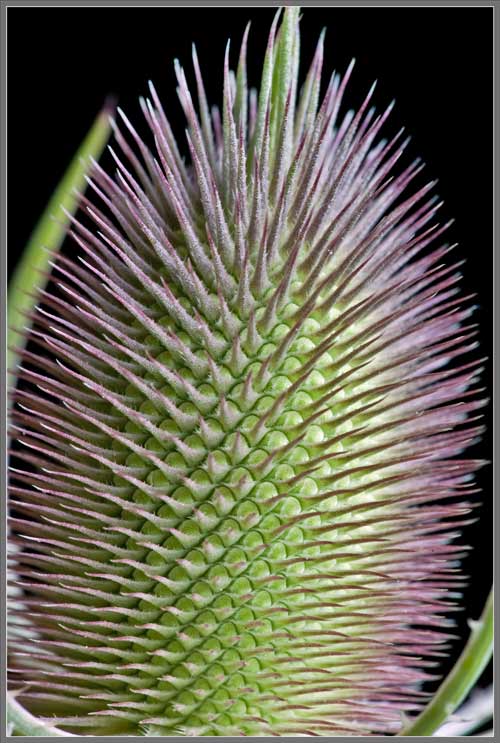

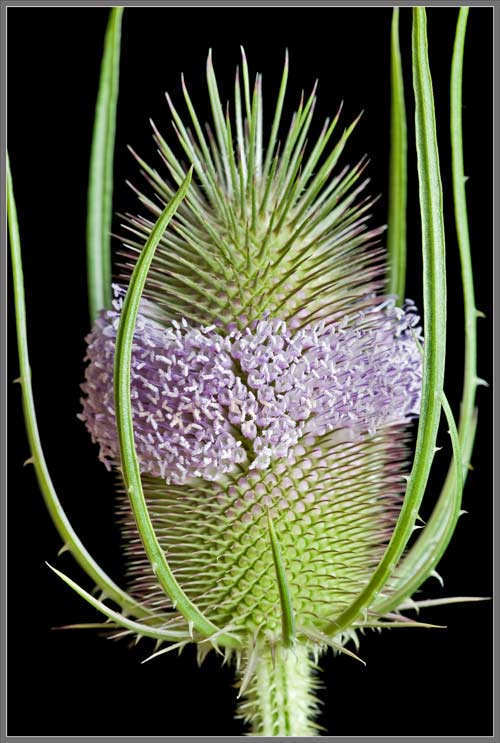

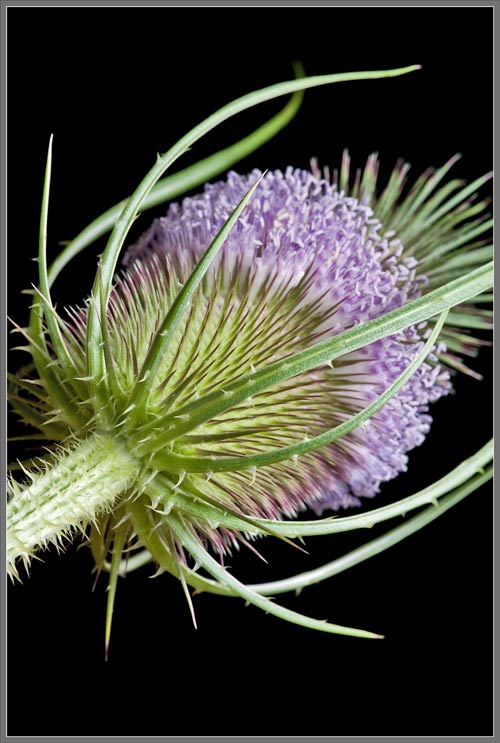

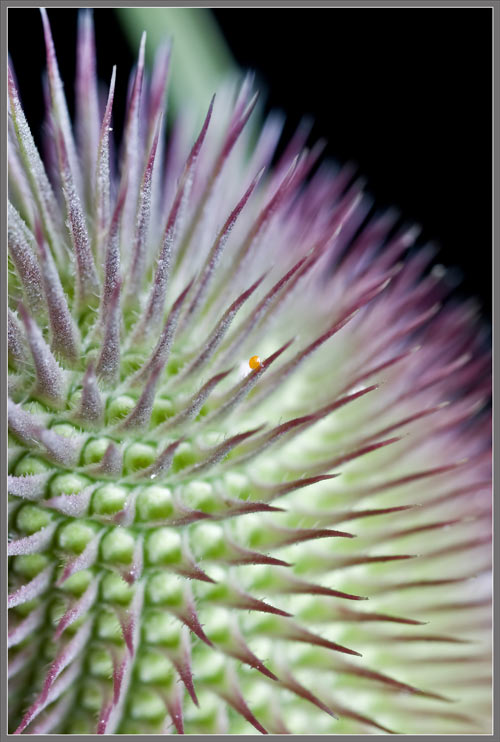

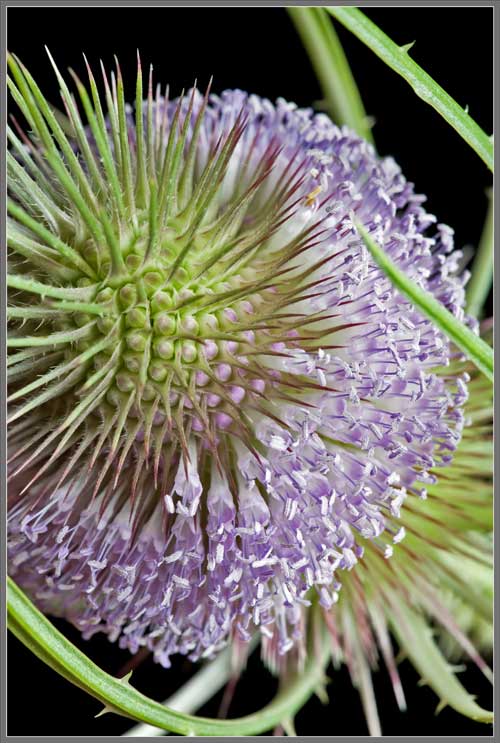

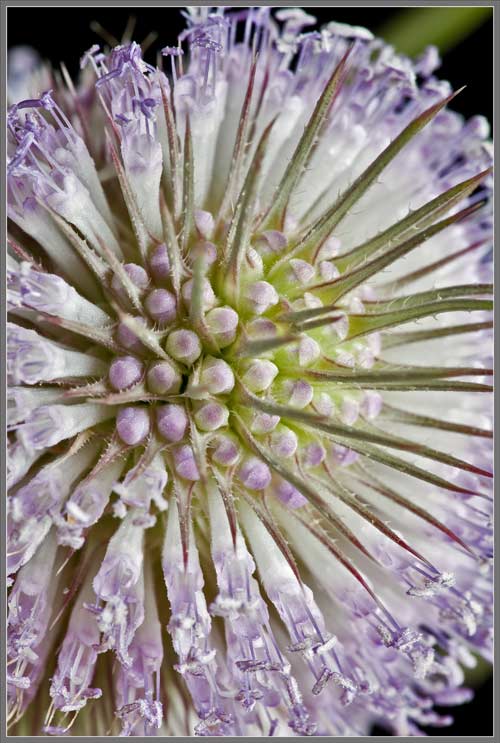

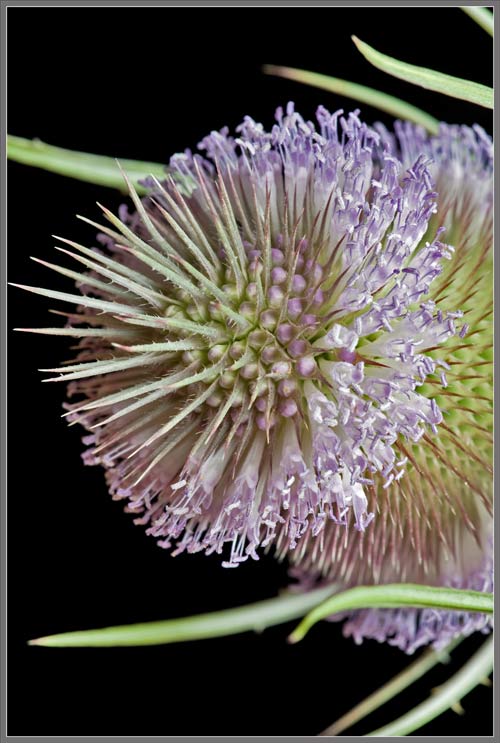

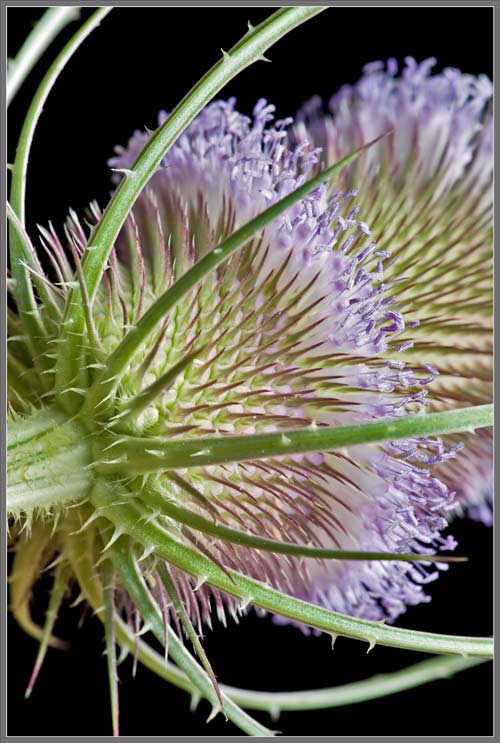

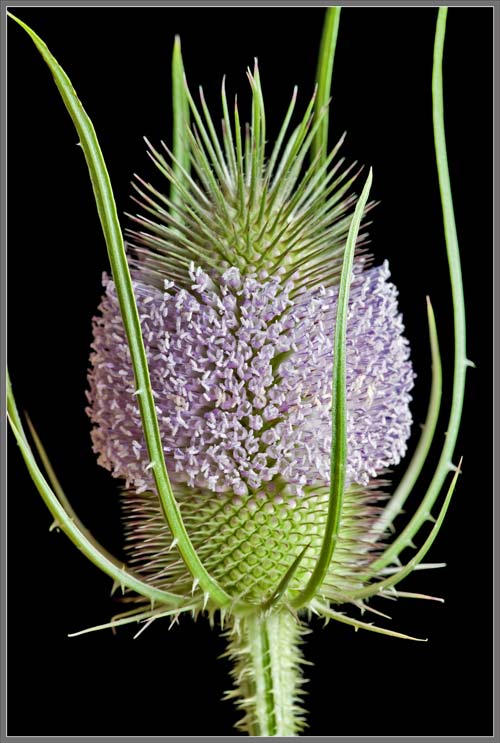

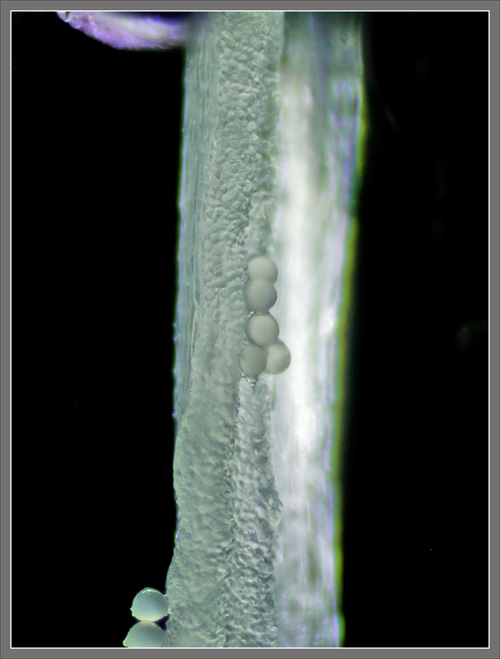

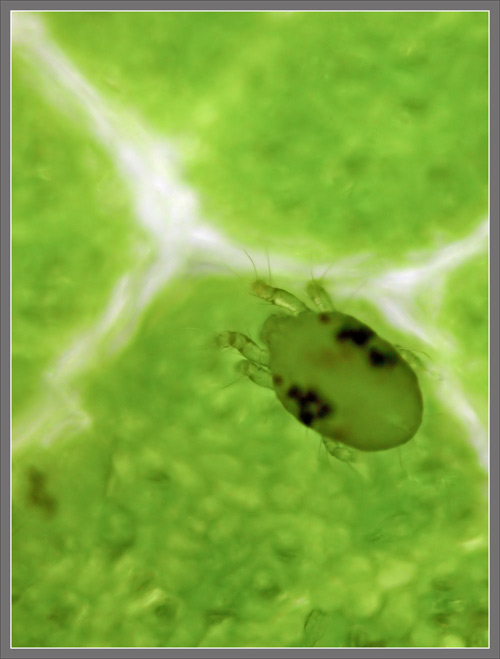

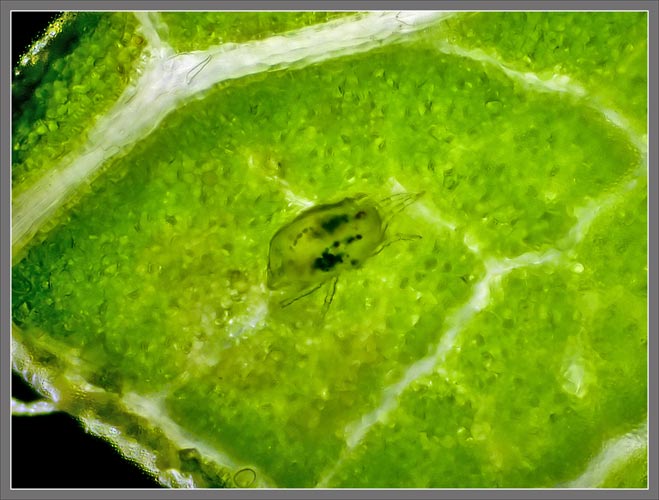

A

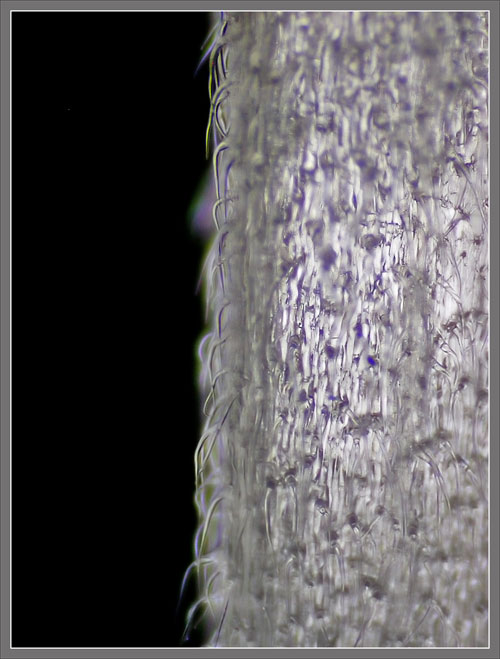

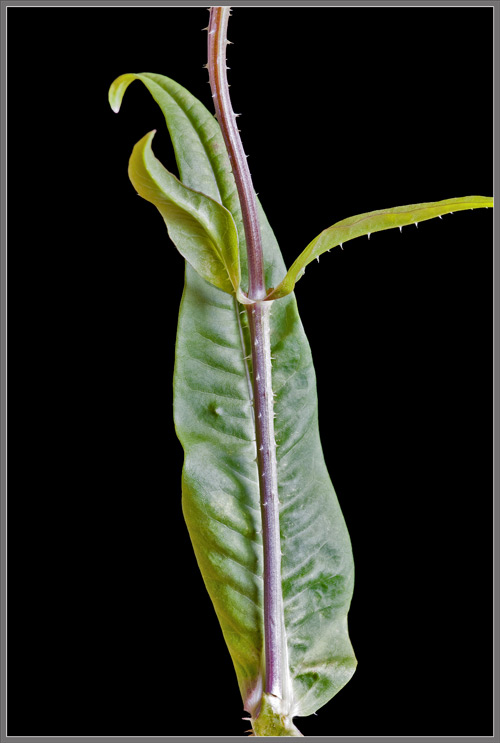

(Second) Close-up View of the

Teasel

|

Published in the July

2010 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .