Exploring classic insect test objects for the microscope: I - Pygidium of a flea

by David Walker, UK

Using certain subjects as tests for microscope optics has a long history (refs. 1,2,7). Some species of diatoms are well documented as tests and still very popular with enthusiasts, but a variety of other subjects including animal hairs and various insect parts are also long established tests and have been described in the Victorian literature.

In collections of old slides, the mounters often labelled the subject when regarded to be a test object, 'Watson' for example. In my brother's and my slide collection there are a variety of Victorian insect test objects and these will be shared in this occasional series in hope they are of interest. As others have noted, given the potential variability of a subject between mounts and the sometimes vague specification of the species, it's arguable if insect parts can be regarded as reliable test objects. But it's both great fun and instructive to inspect these slides while consulting the old books and to repeat the studies they recommended. The enthusiast nowadays can also try techniques developed since the Victorians such as phase and interference contrast if available.

Pygidium of a flea

The author's example is a Watson mount and is still in beautiful condition after all these years; Watson are my favourite Victorian mounters with their high quality mounts and simple but elegant oval labels and neat script. The pygidium in a flea is described by Imms as the 'dorsal sensory plate' on the ninth segment (ref. 3). The species isn't stated but the textbooks usually discuss Pulex irritans, the human flea in this context as a test.

Griffith and Henfrey in their impressive tome 'The Micrographic Dictionary' (ref. 4) mention the 'pygidium of PULEX' under the 'test object' entry as an 'excellent test-object mounted in as small a quantity of balsam as possible'. The attractive Frontisplate in this book of 'Test objects' also has images of the pygidium, see below. Edmund Spitta in his book 'Microscopy' discusses the flea pygidium with some splendid photomicrographs (ref. 5). The latter is my all time favourite Victorian book, he discusses and illustrates in great depth diatoms and other subjects as test objects; the quality of the imagery is humbling even to the modern enthusiast using modern objectives and cameras.

|

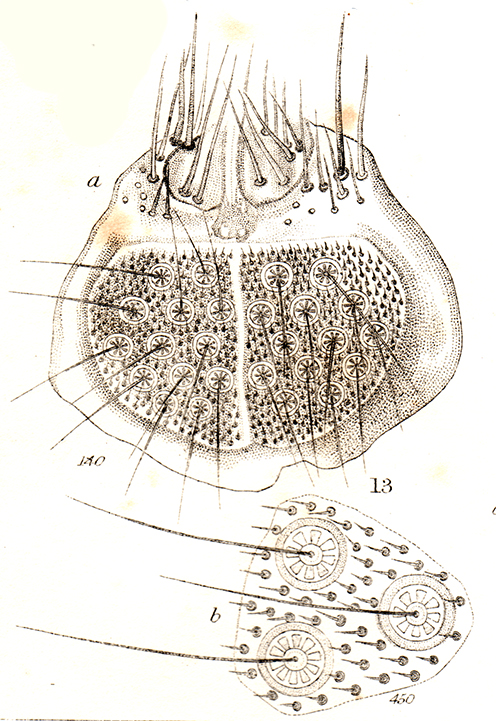

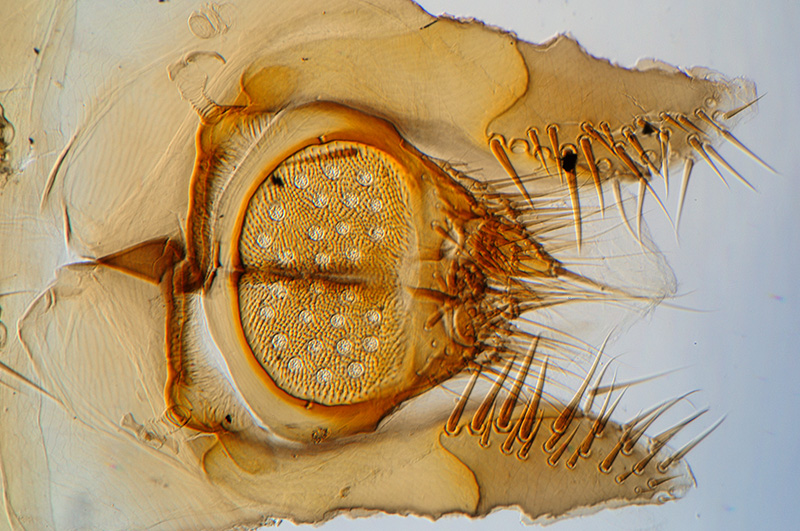

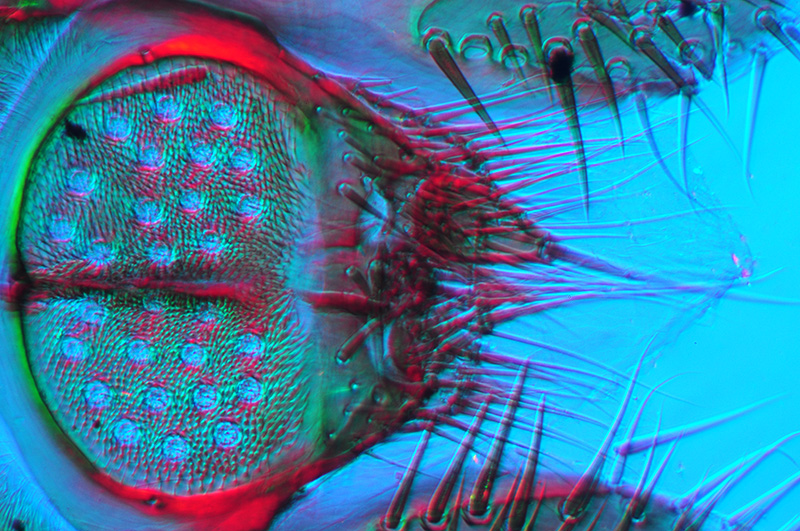

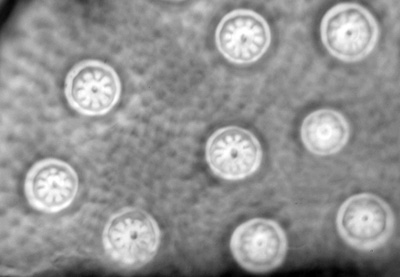

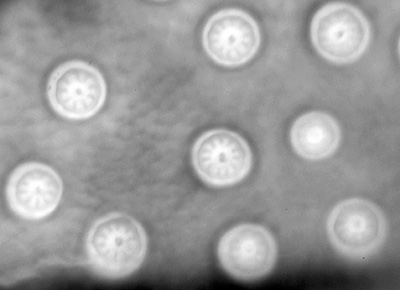

Right: Pygidium of a flea from frontispiece plate 'Test Objects' in the 'The Micrographic Dictionary' 3rd edition, 1875, (ref. 4). Other subjects in this dense plate have been cloned out for clarity. The three dimensionality of the subject is clearly shown. Hairs protrude from the so-called 'wheel discs' as do the hairs surrounding the plane of these discs and the larger hairs 'above' these discs. Far right: The author's example of this subject. The maker's name format and address dates it between 1882-1908 (ref. 6).

|

|

The pygidium as a test object is perhaps not as well known as some others eg. a blowfly mouthparts but it's certainly worth seeking out as a prepared slide. It is a striking subject in its own right and has quite a complex three dimensional structure.

It's worthwhile exploring different lighting techniques that may be available to see how they compare in accurately revealing the features. Shown below are brightfield/oblique, crossed polars, phase and interference contrast with varying success.

Zeiss 10x NA0.32 planapo objective, brightfield with slight oblique from an offset phase condenser's brightfield port. This low power objective shows the gross features with enough depth of field to image most of the hair structure. Horizontal field width 710 µm.

Griffith and Henfrey (ref. 4) remark that for a 1½ to 2 inch objective (ca. 6.5x and 5x on a 10 inch tube) 'the general outline and hairs should be distinct'. The slide is quite thick and coverslip thickness unknown so not sure if there's any image degradation with sensitive objectives.

Spitta (ref. 5) notes the importance of ensuring that the mount has been made the correct way up, i.e. with wheel disc hairs in the first plane of focus when focussing down onto slide.

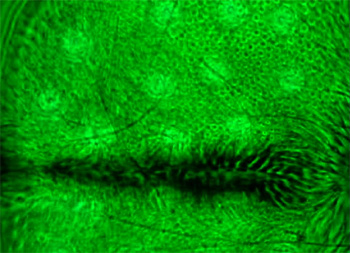

Zeiss 10x NA0.22 planachro phase. Phase can give rather muddled results with thicker objects but does emphasise the larger hair structures quite well, although the 'wheel disc' and surrounding small hairs do become somewhat less clear.

Zeiss 16x NA0.35 planachro with Nomarski interference contrast. Overall by trying various objectives I didn't think interference contrast worked very well for this subject. Perhaps a good reminder that the various contrast enhancement techniques are complementary, some may be more suitable than others depending on subject type, thickness, birefringency etc. Another technique the author didn't find too successful was annular oblique (COL).

Zeiss 16x NA0.35 planachro, slight oblique with crossed polars and lambda tint plate. The depth of field is greater with same objective as above exploiting the birefringent properties.

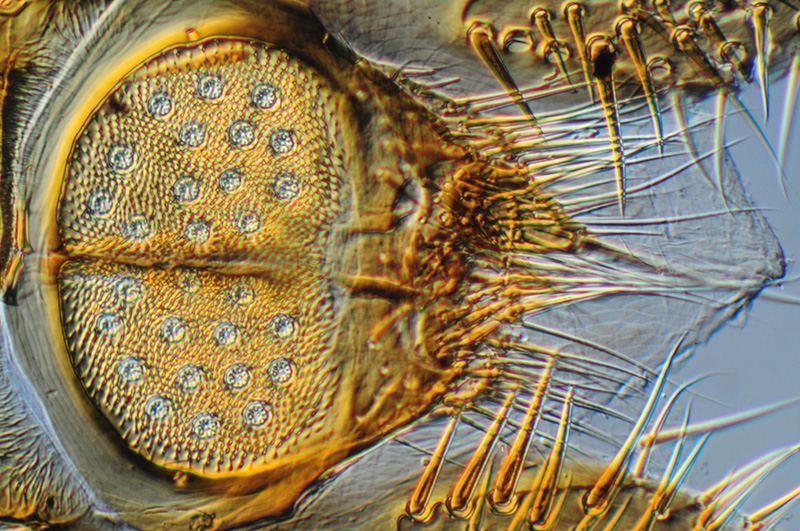

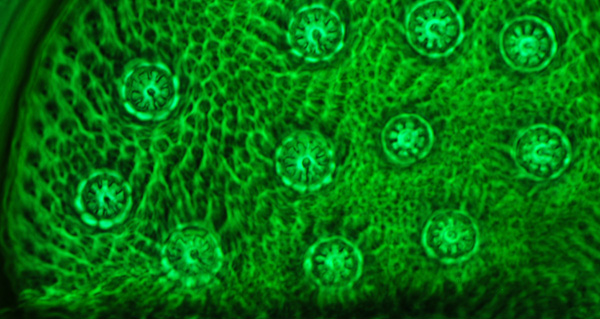

Zeiss Neofluar phase 40x NA0.75 objective, phase; this shows the wheel disc structure quite well, better than brightfield, but unsurprisingly gives a rather unclear idea of the surrounding 3D hair structure in this single image plane. The wheel discs are ca. 10 µm in diameter.

Zeiss Neofluar phase 40x NA0.75 objective, interference contrast, which again shows the wheel disc structure quite well. Because of the optical sectioning, the hairs in this plane aren't seen at all but may suggest the hairs are in depressions or on raised bumps.

The pygidium is a good example of the importance of continually focussing through a subject which has depth to determine its features in three dimensions. I haven't attempted the modern image stacking to try and show this but may need care to ensure a muddled result isn't obtained. Instead, a film clip is presented below showing the microscope focussing down from the upper hairs through to the so-called 'wheel discs'.

Video clip (ca. 2 Mbytes) following through the focus from highest plane to lowest plane. The video window is larger than the still shown. Zeiss 40x NA0.75 objective, phase.

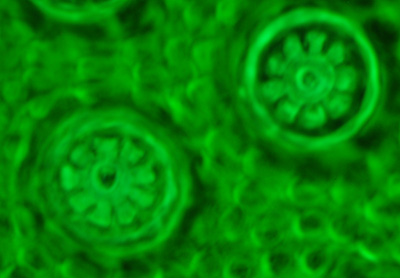

Zeiss 100x NA1.30 Neofluar phase, showing the wheel disc structure. The spot at centre of the discs is the hair base pointing out of the plane of the screen.

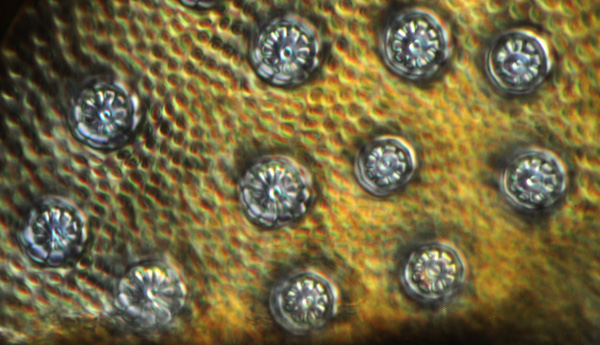

One of the tests Spitta describes (ref. 5) for the pygidium is assessing the image quality of the wheel discs at full aperture of the objective and when stopped down to two thirds. He uses a 1/6th objective NA0.95 (ca. 40x on a 160mm tube scope) for his images but a Zeiss Neofluar 40x NA0.75 was used below to repeat this trial. Interested readers should refer to ref. 5 for Spitta's discussion of this test. Spitta remarked that some objectives of the time with 'poorly corrected outer zones' showed the wheel discs as 'dots' instead of the 'cuneiform spokes' when used at full aperture.

Zeiss Neofluar (phase) 40x NA0.75 objective, brightfield. Left - condenser iris set 2/3rds aperture of objective's back focal plane, right - full aperture of objective. Although contrast and depth of field drops at full aperture, the wheel disc shape is still maintained.

Spitta's images of this trial are superior to my attempts, his book plate images have better contrast than the digital SLR images above. Although the imagery in most of his plates are notably very contrasty for often difficult low contrast subjects like diatoms.

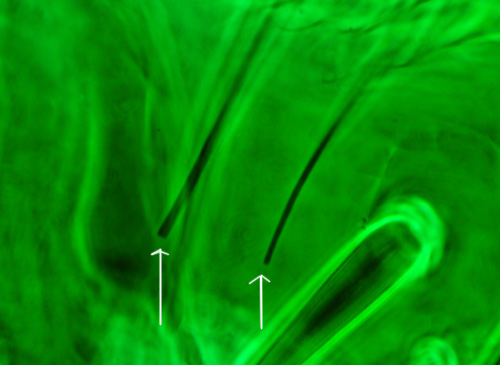

Zeiss 100x Neofluar phase showing the tips of hairs (arrowed) that radiate from the wheel discs. Spitta notes (ref. 5) that 'each should appear as a delicate filament with nearly parallel sides, only tapering to a point not far from their ends, and then somewhat suddenly'. In the present author's example, the ends of most hairs inspected ended very abruptly (I'm uncertain if this is genuine or whether they had broken off during slide preparation). Of the techniques tried, phase was the best technique to show these hairs in high contrast.

As remarked earlier, because of their potential variability, such subjects can't really be regarded as objective tests for microscope optics. However, because this type of test subject is well documented, studying them while consulting the work of the early writers is very worthwhile; you almost feel to be in the virtual company of these eminent microscopists while repeating the studies which they so eloquently describe.

Comments to the author David Walker are welcomed.

Acknowledgements: With thanks to my brother Ian for loan of the slide and access to ref. 4. Also thanks to Brian Stevenson for providing a copy of ref. 2.