|

|

A

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Tragopogon dubius) |

|

|

A

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Tragopogon dubius) |

A

casual glance at this bright yellow wildflower might leave the observer

with the impression that it is a dandelion on steroids! It is in

fact a member of the same family, (aster), but there are many

differences that contribute to Yellow Goat’s-Beard’s uniqueness.

The most obvious difference is

size. Goat’s-Beard can grow up to a metre in height, and the

single composite flower-head

containing both ray and disk flowers can have a diameter up

to seven centimetres. This large flower-head opens and twists

slightly towards the sun each morning. In the early afternoon,

the flower-head closes again. The English poet, dramatist and

essayist Abraham Cowley (1618 - 1667) wrote the following about the

Goat’s-Beard plant.

The propensity for early closing

resulted in old country names of “Noon-flower” and

“Jack-go-to-bed-at-noon” being given to the plant. The genus name

Tragopogon

comes from the Greek words tragos, meaning

‘goat’, and pogon

meaning ‘beard’. This is in reference to the seed-head of the

plant (which will be shown later). The species name dubius can be

translated as ‘doubtful’, and may refer to the fact that, due to

hybridization with other similar species, identification may be

uncertain.

One of the most important

characteristics of Yellow Goat’s-Beard is the ring of sharply pointed

modified leaves called bracts

which are arranged in a radial pattern beneath the flower-head.

In this species these bracts must be longer than the petals. The

first photograph in the article, and the two images below show these

bracts. Note that the number of bracts is variable, but most

plants have about ten.

A swollen growth at the base of the

flower-head is another characteristic of Yellow Goat’s-Beard. It

can be seen in the right-hand image above.

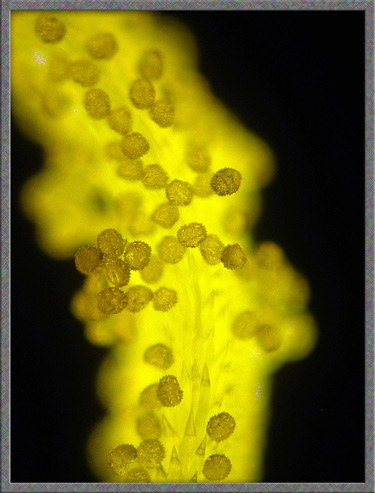

The first flowers to bloom in the

composite head are the outer ray flowers to which the yellow petals,

called ligules, belong.

The pale green, yellow tipped columns at the centre of the head are

immature stamens.

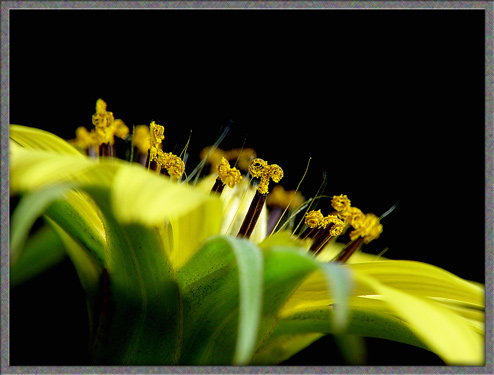

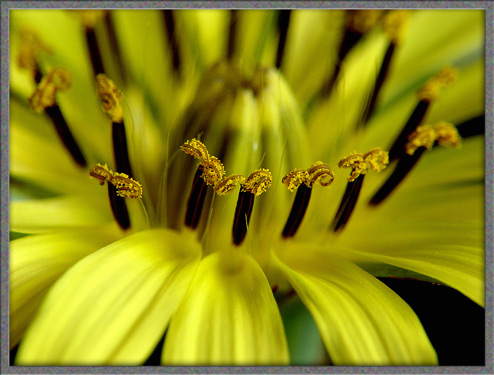

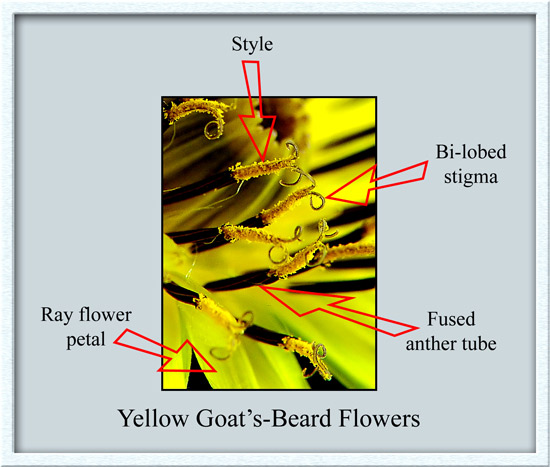

The three images below show side

views of the outer ray flowers. The dark, almost black columns

are actually tubes formed by fused anthers

(the male pollen producing structures). Growing up through each

of these tubes is the style, which supports a two-lobed stigma (the female pollen accepting

structure). It has been my experience that the beautifully curled

lobes of the stigma exist for a very short time, and they soon

straighten out to a straggly ribbon form. All three images show

that the stigma’s surface is coated with tiny pollen grains.

The unkempt appearance of the

stigma lobes after a period of time can be seen in the following image.

A closer look reveals more

detail. In particular, notice that each of the anther columns

forming the central structure in the image, is divided at its tip by

fine black lines, into five sections. These are the five anthers

which are fused to form a particular column. Given time, the

stigma and style will grow up through this tube and beyond it.

As the flower-head matures, the

central columns straighten slightly to reveal a dark centre.

Compare the two images below with the one above, in which no dark

centre is visible.

Two

further images of a flower-head are shown below. Note the swollen

base in the first image.

Under the microscope, the details

of a fused column of anthers can be seen. Note that three of the

five anthers are visible in the photomicrograph, each with a triangular

top. The yellow column protruding from the end is the style.

The highly magnified central

longitudinal ridge of one of the anthers is shown below.

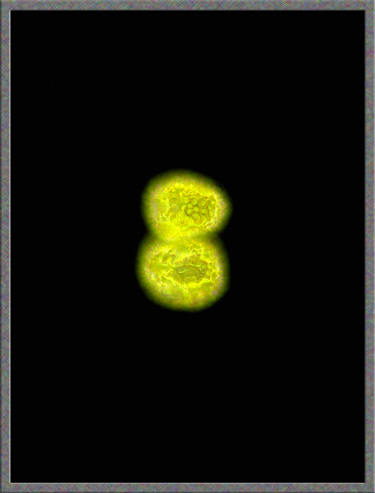

In the following photomicrograph,

the bi-lobed stigma has just pushed out of the anther tube. As

time passes, it will grow out still farther, revealing the style that

supports it.

A much higher magnification image

of the exit point of the style is shown below. Note the hair-like

protuberances on the style’s surface that tend to capture any pollen

that come into contact with them.

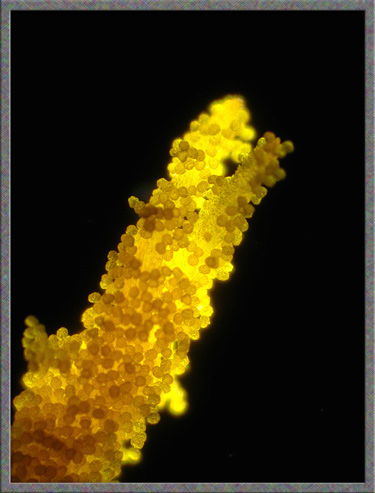

Two further images reveal the many

pollen grains which have become stuck to the surface of stigma and

style.

The surface of a pollen grain

appears to be pock-marked by many tiny depressions.

A Second Species

(Meadow Goat’s-Beard ?)

The flower-head in the two images

below looks remarkably like Yellow Goat’s-Beard, but the pointed green

bracts are shorter than those of that species. This is ‘probably’

Meadow Goat’s-Beard, Tragopogon pratensis.

I say probably, because although pratensis does

have shorter bracts, it is not supposed to have the swelling beneath

the flower-head - and this one clearly does. Welcome to the

nightmare of identifying Tragopogon species! One possibility is

that all of the many Tragopogon species tend to form hybrids when

unknowing insects carry the pollen of one plant to another of a

different species. The resulting hybrids have a mixture of the

properties of both plants. This may bring joy to a plant

taxonomist’s heart, but not to mine!

The swelling at the base of a

flower-head is particularly noticeable while still in bud form.

The three photographs below

demonstrate how similar the Meadow Goat’s-Beard flower-head is to that

of the Yellow Goat’s-Beard’s.

Back to Yellow

Goat’s-Beard

Once the flower-head has finished

blooming, a remarkable thing happens. The bracts close up around

the fertilized flowers, completely hiding them from view.

If the bracts are cut away, it is

possible to see the developing seeds and pappae, composed of the hairs that

will eventually form the dandelion-like parachute. Note, in the

image on the right, that the spiked seeds are beige in colour.

The white columns beyond the narrow green rings are composed of the

fine white threads which will eventually form the parachute.

The higher magnification

photographs which follow reveal details of the developing seeds and the

green rings which are the point of attachment of the pappae.

As can be seen in the two images

below, the seeds, called achenes

are covered in spikes which form on the many longitudinal ridges.

It is

interesting to note that if several of the outer achenes are removed,

those visible in the inner core have greatly reduced spikes on their

surfaces.

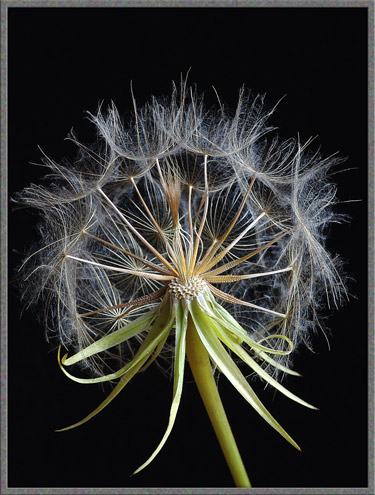

Once the seeds have sufficiently

matured, the bracts re-open and the pappae on their long stalks begin

to dry out and open into parachutes.

When this process is complete, the

startlingly large (up to 10 centimetre!) globe-shaped plumed head is

revealed. These balls of parachutes completely dwarf those of the

largest dandelion.

A

gust of wind is all that is needed to dislodge seeds from the white pad

to which they are attached. (For this photograph, I acted the

part of the wind in order to remove the front-most achenes.)

While searching in the field with

my trusty magnifier for a photogenic specimen, I noticed the seed-head

below. Several of the central seeds and pappae have failed to

grow properly and have formed an interesting and unique basket-shaped

cage. In the last image, note the strange shape of the

depressions in the pad to which the seeds are attached.

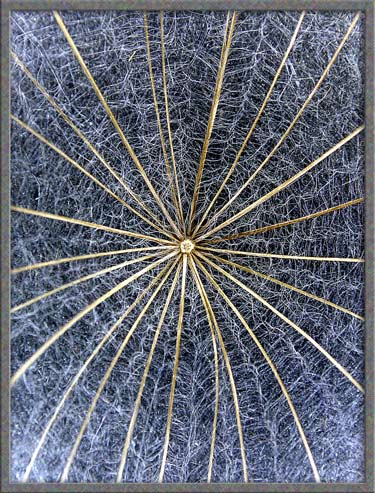

The parachute of a Goat’s-Beard

seed is almost flat and the surface is perpendicular to the column that

attaches it to the seed. Strong (beige) radial ‘arms’ attached to

the central column hold fine (white) fibers that completely fill the

space between the arms.

Under a higher magnification, it

can be seen that these fibers form a tangled web between each pair of

radial ‘arms’.

When I first became interested in

the macro-photography of wildflowers two summers ago, Yellow

Goat’s-Beard seed heads were abundant. Although it was only

August, I could find no flowers. (To be truthful, I did find

several very misshapen examples that were too ugly to

photograph.) With less than perfect patience, I had to wait until

this past summer to obtain images of flower-heads. Strangely,

this summer, which was much cooler and wetter than the previous one,

proved to be ideal for Yellow Goat’s-Beard. Flowers bloomed right

up to the middle of September! It was worth the wait. This

plant is one of my top ten favourite wildflowers.

Photographic Equipment

The photographs in the article were

taken with an eight megapixel Sony CyberShot DSC-F 828 equipped with

achromatic close-up lenses (Nikon 5T, 6T, Sony VCL-M3358, and shorter

focal length achromat) used singly or in combination. The lenses screw

into the 58 mm filter threads of the camera lens. (These produce

a magnification of from 0.5X to 10X for a 4x6 inch image.) Still

higher magnifications were obtained by using a macro coupler (which has

two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4 Olympus

SLR lens to the F 828. (The magnification here is about 14X for a

4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz SM-Pol

microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix

4500.

Note:

Since the photographs in this article were obtained over a period of

two years, my Sony DSC-F 717 and Nikon 4500 were used to take the

earlier photographs. They can be distinguished by the fact that

the gray frames around them are of slightly greater width.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

A Flower Garden of

Macroscopic Delights

A complete graphical index of all

of my flower articles can be found here.

The Colourful World of

Chemical Crystals

A complete graphical index of all

of my crystal articles can be found here.

Published in the July

2009 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .