|

|

A

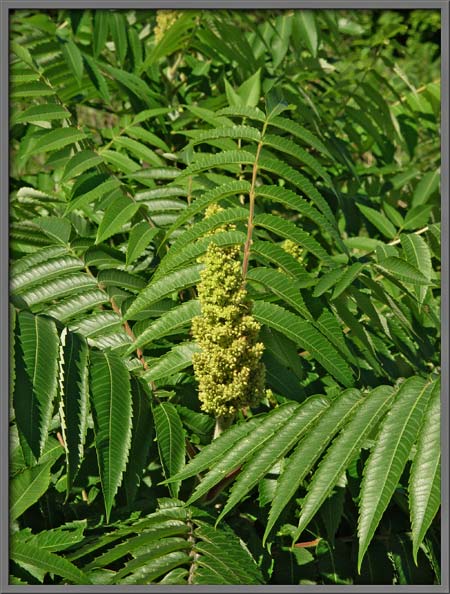

Close-up View of the "Staghorn Sumac" (Rhus typhina) |

|

|

A

Close-up View of the "Staghorn Sumac" (Rhus typhina) |

The

staghorn sumac is a small tree that commonly grows in large groups in

the wild. It is often used by landscapers as a decorative

addition to residential yards and municipal parks. Its common

name is derived from the fact that the branches are covered by dense,

extremely soft hairs, and resemble the "velvet" on a deer’s

antlers. As well as being decorative, the trees are a source of

seeds for both songbirds and gamebirds during cold Canadian

winters. Historically, Native American Indians made a drink from

the plant’s crushed fruit. The tannin-rich bark and leaves also

provided tanneries with a natural tanning agent.

It is interesting to note that a sumac tree is either male or female,

but not both. This trait is referred to as “dioecious”.

The “Male” Sumac Tree

The image below shows part of a male tree. The yellow-green

pyramidal structure at the center of the image is called a panicle, and

consists of many tiny flowers.

Sumac leaves are compound, and the toothed leaflets are positioned on

the stem opposite one another.

A high magnification reveals the multitude of tiny white hairs that

cover the stems. It is these hairs that give the plant its common

name “staghorn”.

The toothed edges of a leaf are clearly visible below. Notice in

the image of the back of a leaf, that the sturdy white rib has many

tiny hairs on its surface.

In June and July, the male sumac trees are covered with panicles of

flowers like the one below. The closer view on the right just

begins to resolve individual flowers.

The image on the left below shows many unopened buds, as well as a few

mature flowers. If you look carefully at the central flower in

the right hand image, you can see five light green petals, five bright

yellow-orange anthers (male,

pollen producing organs), and, at the

exact center, three circular pale yellow structures that form the

stigma (female, pollen

accepting organ). Surprise! You

might expect the flowers of the male staghorn tree to have only

anthers. In reality most flowers are “perfect” (they have both

stamens & pistils).

Each staghorn sumac flower is 4 to 5 mm in diameter. In many

flowers there is a hint of reddish-brown at the very center.

Note: The back end of a

visiting insect with almost perfect

camouflage colouration can be seen at the right edge of the first

image, just below the mid-point.

It is evident below that each anther is divided longitudinally by a

deep groove.

At higher magnification, the pale white filament supporting each anther

becomes visible. The orange-brown center of a flower can be seen

in the right hand image.

Under the microscope, the deep groove at the center of an anther can be

seen to be filled with pollen grains. The right hand image shows

the grains to be ellipsoidal in shape.

Pollen grains stick to the surface of the filament supporting the

anther.

For some reason, some pollen grains are stuck together in long “chains”.

Others can be seen below, adhering to form a convex shape.

Phase-contrast illumination shows the rough surface, and longitudinal

groove of each grain.

At the very center of the flower, there is a three-lobed stigma

supported by a three-columned style.

It is interesting to note

the almost perfectly spherical tip of each stigma lobe, and the way in

which each sphere is clasped by the style. The nature of the

orange colouration at the base of the stigma-style is revealed in the

image on the right. The centers of the cells forming the tissue

are orange in colour.

Once the flowers have finished blooming on the male sumac tree, they

shrivel up and drop off. For the rest of the growing season, the

tree has only leaves; it does not develop the colourful “fruit”

of the female tree discussed below.

The “Female” Sumac Tree

The pyramidal panicles of flowers on the female tree are less random in

shape than on the male counterpart. A typical such panicle can be

seen below, shortly after the flowers have finished blooming.

Notice in both images, how densely packed the flowers are in a panicle.

A closer view shows the dense packing of the many reddish drupes

(fruit) that form the panicle. Notice the three black dots at the

top of each drupe. These are the darkened tops of each

three-lobed stigma. Each drupe contains a single seed with a hard

coating. The mature drupes may last through the winter, if they

are not eaten by birds. They eventually turn dark brown.

Higher magnification reveals more structural detail. At the base

of the pistil (stigma-style),

the ovary has swollen into a red, roughly

spherical fruit, topped by the darkened stigmas, and circled by the now

beige-green petals . Each flower has a multitude of fine hairs at

its base.

The following sequence of images was taken a year earlier than the

former ones. The panicles of fruit are several weeks “older” than

those shown before.

At this later stage, most of the blackened stigmas have fallen from the

flowers, leaving only the swollen fruit. Each drupe is yellow in

colour, but it is covered with groups of dense bright red hairs that

are stuck together at their tips. What an extraordinary fruit the

staghorn sumac possesses!

A year after the preceding images were taken, I went back to the same

tree and had another look at a panicle of drupes.

This time, notice that the drupes have swollen to the point that they

now dwarf the remaining flower petals.

Staghorn sumac is highly prized for the coloration of its fruit, and

its brilliant autumn foliage. It is unfortunate that the display

of coloured leaves (see below) lasts for such a short time. The

late autumn winds soon blow them from their branches, leaving only a

network of red stems and the darkening panicles of fruit.

Photographic Equipment

About half of the photographs in the article were taken with an eight

megapixel Canon 20D DSLR and Canon EF 100 mm f 2.8 Macro lens. An eight

megapixel Sony CyberShot DSC-F 828 equipped with achromatic close-up

lenses, (Nikon 6T, Sony VCL-M3358, and shorter focal length achromat

used singly or in combination), was used to take the rest of the macro

images. The lenses screw into the 58 mm filter threads of the camera

lens. Still higher magnifications were obtained by using a macro

coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal

length f 1.4 Olympus SLR lens to the F 828. (The photographs in the

article were taken over a two year period.) The photomicrographs were

taken with a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using a dark-ground condenser),

and a Nikon Coolpix 4500 camera.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

Published in the July

2007 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .