Sea urchin : a stinging but amazing animal |

by Jean-Marie Cavanihac, France |

||||

|

The weather is nice, the sea water is warm, you are going to walk along the seashore, among wave foam which is reaching the beach and refreshing your feet.... Suddenly you sense a puncture under your toe: a sea urchin, hidden under a clump of algae, has defended itself against your foot's aggression! You are angry with the creature, because your toe is painful and also because urchin spines are very difficult to remove. But spines are its unique and passive defence against predators. (Even in its own family: the starfish which is also an ECHINODERM doesn't hesitate to eat its cousins!) (Picture: Strongylocentrotus.) |

| To

console the unfortunate walker, some stages of sea urchin

development are very beautiful to observe (and with no

danger). At first sight, this echinoderm doesn't have an

attractive appearance and it seems not to have

interesting microscopic features. It is even repellent: a

popular French expression about a man's avariciousness

is: 'He has sea urchins inside his pockets'! I hope that this article, which doesn't want to be an exhaustive lesson on its family, will permit me to introduce some amazing and lesser known aspects on its anatomy and mainly to illustrate them. (See footnote to learn more on it.) |

| Sea urchins appeared on earth around 500 millions years ago. Nowadays they are often used as models for exploration of the development process in living organisms. A classical biology course will cover in vitro fertilisation of urchin eggs and their observation. It is possible to obtain eggs and sperm from mature sea urchins, although there's a little problem: male and female specimen are difficult to identify - but in some species, males are darker (less coloured) than females. Eggs and sperm are released from the five gonads, through the gonopores on the opposite side of the mouth (top). Eggs are orange-coloured and sperm is white. Eggs can be diluted immediately with sea water, but sperm must be aspirated from the pore and stored like this. The two samples can be cooled separately and used until two or three days later for fertilisation by mixing eggs and sperm very diluted in sea water. |

| Gastronomic note: in the French Riviera mainly, sea urchins are greatly appreciated by gourmets who cut urchins in two halves and eat the roes. Personally I don't eat urchins, I prefer to observe them! |

| Like

many marine animals, sea urchins produce a great number

of eggs, which are carried away by currents and only few

of them become adults. When an egg is fertilised by sperm, its envelope increases in size, divides itself in two, then four, then eight cells and so on. This process occurs freely in sea water. The three pictures below show: the unfertilised egg, fertilised egg and four cells stage. When the cell number reaches around 64, (after 6 divisions in two or three hours) a swimming ciliated larva (the blastula stage) hatches from the egg membrane. The first organ which appears is the anus; the mouth appears a little later at the other end of the gut (the gastrula stage). (Unfortunately I have no picture to illustrate this stage.) |

|

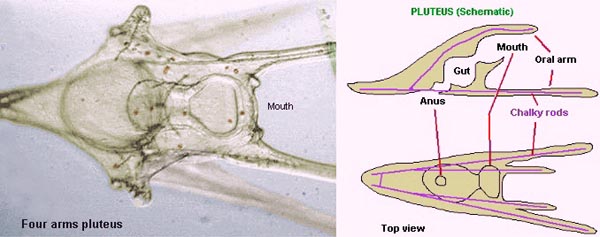

| You are probably going to think 'nothing very exciting' but wait for the following steps: a week later, the larva's appearance is fully modified: a draft of the skeleton begins to appear and two long oral arms are formed on the embryo and they are reinforced by internal calcareous rods. The larva looks like a little pyramid or an arrow. This larval stage is called PLUTEUS (pictures below). Note that larvae don't swim in the direction of the 'arrow' but with the mouth in front. The oral arms probably helps to conduct food towards the mouth.. |

|

| In the picture below, both mouth and gut are clearly visible. A closer view of the 'arms' shows the cilia on them and also around the mouth. The cilia allow the animal to move forward with a majestic slowness. At last a subject we can observe at leisure! |

|

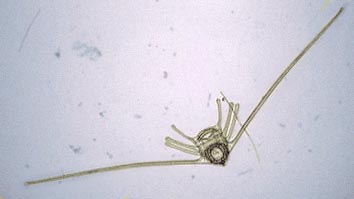

The arms develop as the larva is growing, Click HERE for enlarged picture

|

A month later a metamorphosis takes place, which produces a baby sea urchin having all the features of the adult stage. The arrow shows detail of a little 'foot' which acts like an adhesive sucker to attach itself to stones or algae. |

|

TO SEE MORE AMAZING FEATURES ON SEA URCHIN GO TO PAGE 2

(OR DO YOU THINK THAT SEA URCHINS HAVE FORCEPS?)

Comments to the author Jean-Marie Cavanihac are welcomed.

Microscopy UK Front Page

Micscape Magazine

Article Library

All photographs © Jean-Marie Cavanihac 2000

Published in the July 2000 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web

problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line

monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

WIDTH=1