My quest for decades now has been to try to combine scientific knowledge and aesthetics. Nature does indeed have its dark side, but there is such staggering beauty as well and an odd item like the cross section of the stem of a plant can provide ample proof. The trick of course, is to get a nice thin section which can be viewed in transmitted light with a compound microscope. Some sections are splendid just as they are, others are greatly enhanced by the use of special stains, and some are spectacular under polarized light. In addition, there are some marvelous enhancements that can be achieved by means of computer graphics.

So, this album is essentially a journey of exploration. I’ll try to keep my comments to a minimum, but those of you familiar with my previous scribbles know that you have a better chance of winning the lottery than my being concise. So, let’s embark on a micro-expedition.

I’ll admit that I have a strong attraction to stained sections under polarized light. And lately, I have been more and more drawn into the evil machinations of computer graphics. I shall, however, endeavor to be honest about what I am doing–all philosophers are always liars. I am a philosopher, so I am a liar, therefore I am telling you the truth.

How do you get thin sections? Buy them! With certain types of specimens, you can make your own, but unless you have a microtome and the skill to use it properly, in the long term, it’s better to find and purchase prepared slides, be they Victorian or from a modern biological supply house.

Thin sections of plant stems and roots, and to a lesser extent leaves, have been a popular subject for microscopists for over 150 years. Microscopists also developed elaborate techniques for staining such sections. The advent of polarizing microscopy opened up another whole dimension with both stained and unstained sections. Some stains provide striking enhancements under polarization. Looking at plant sections can stimulate ones curiosity and you might well end up learning more about certain botanicals than you ever would have imagined.

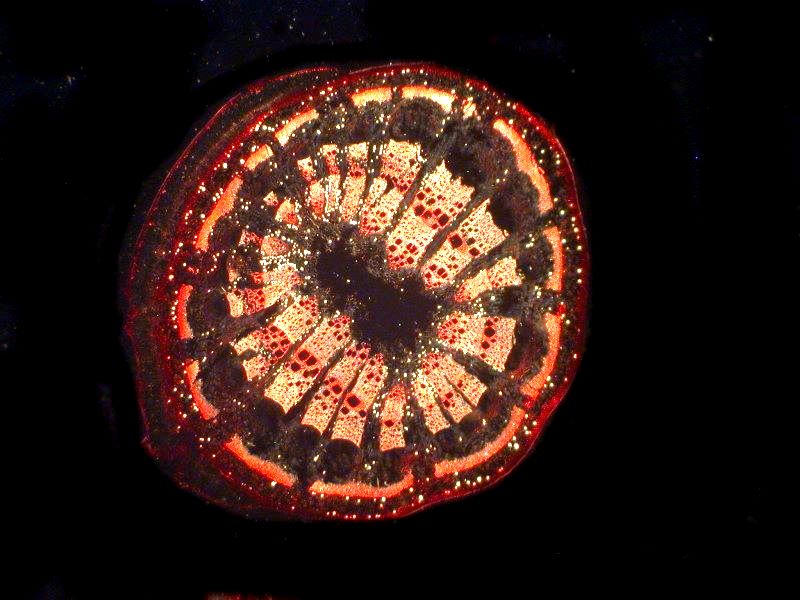

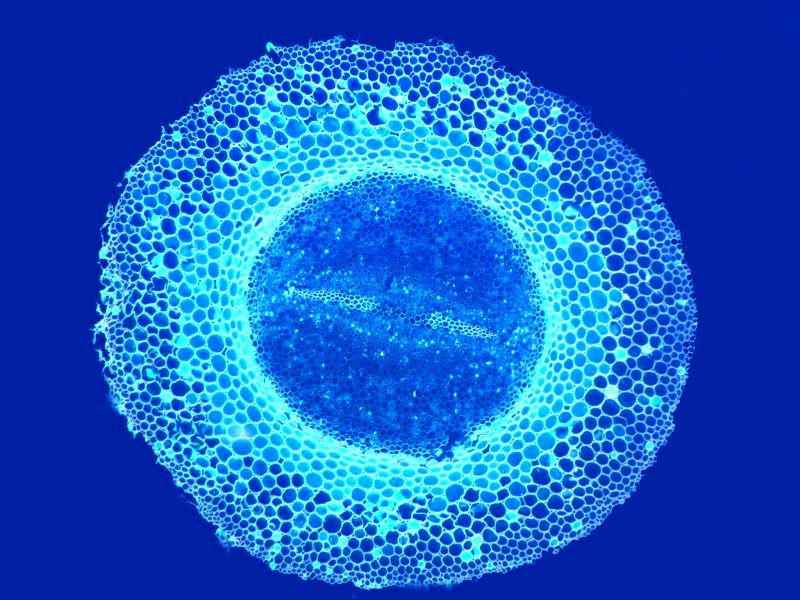

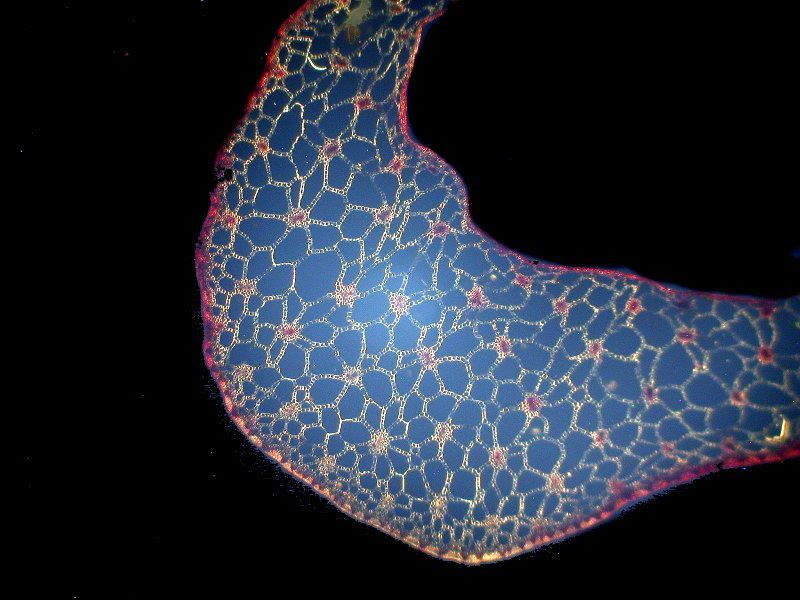

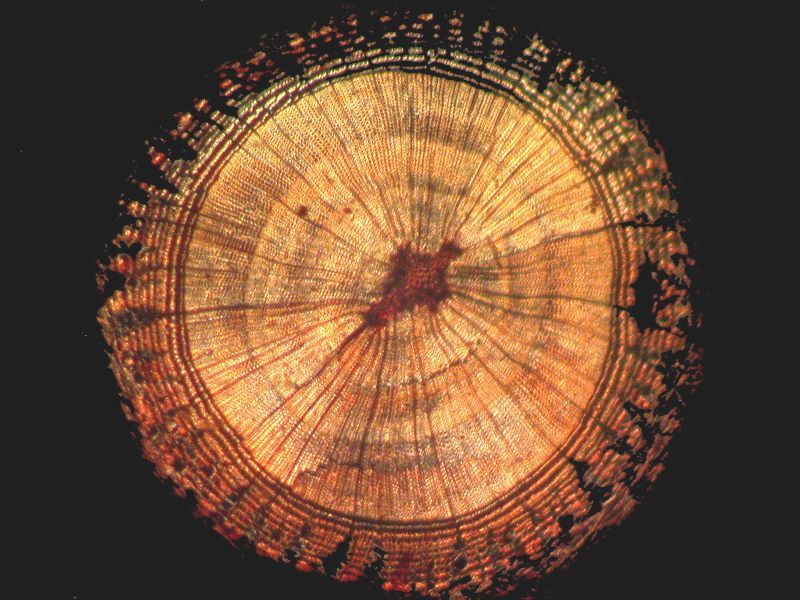

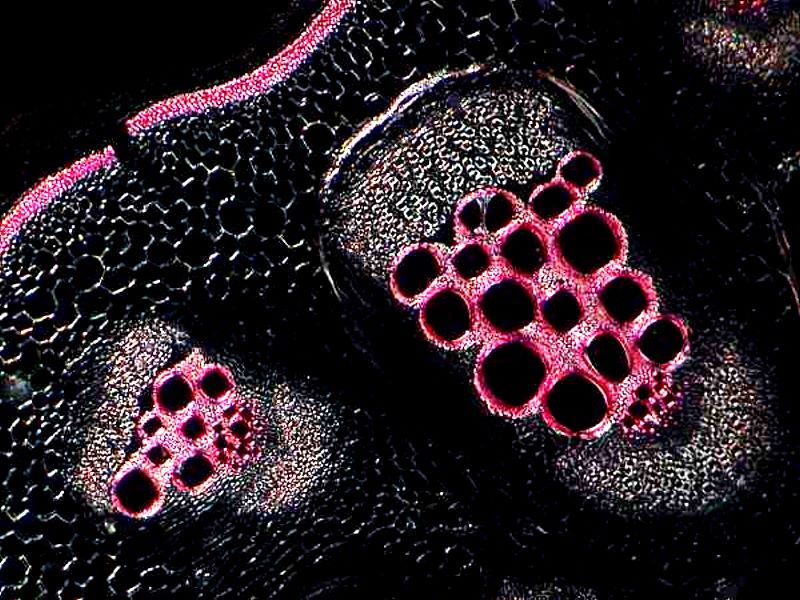

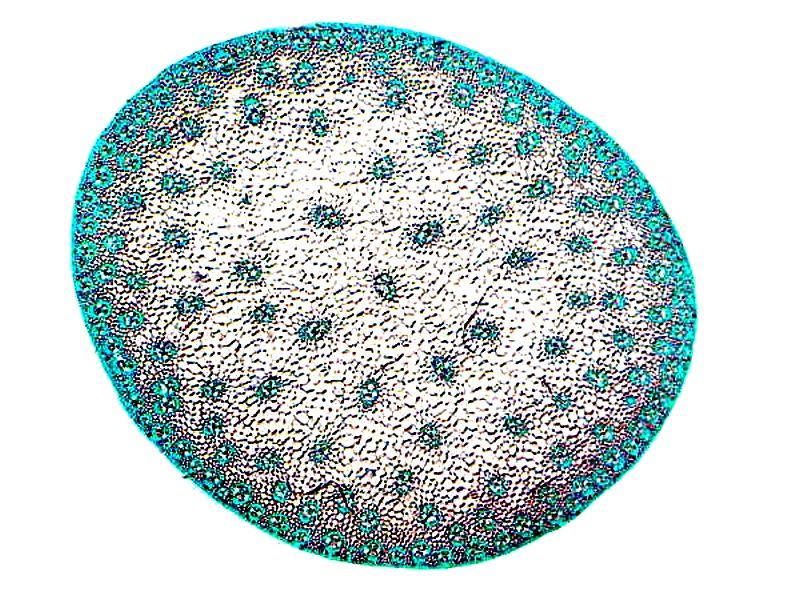

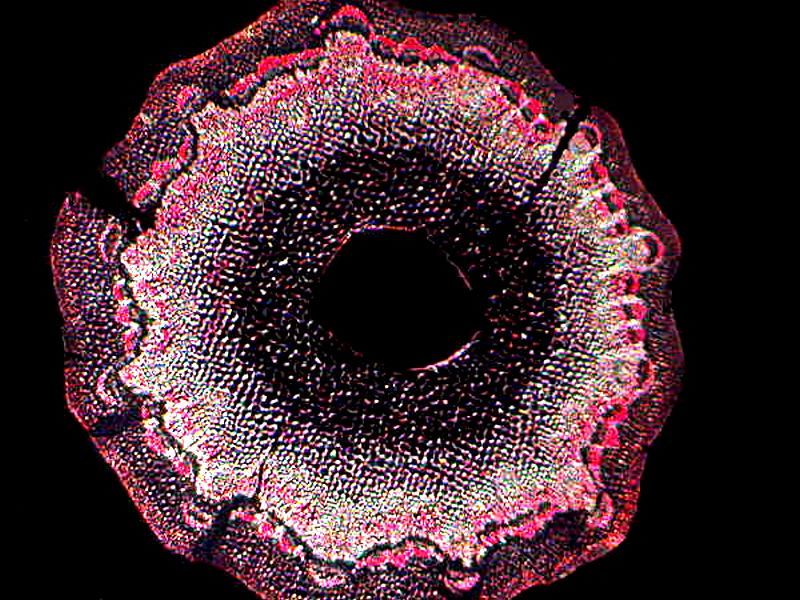

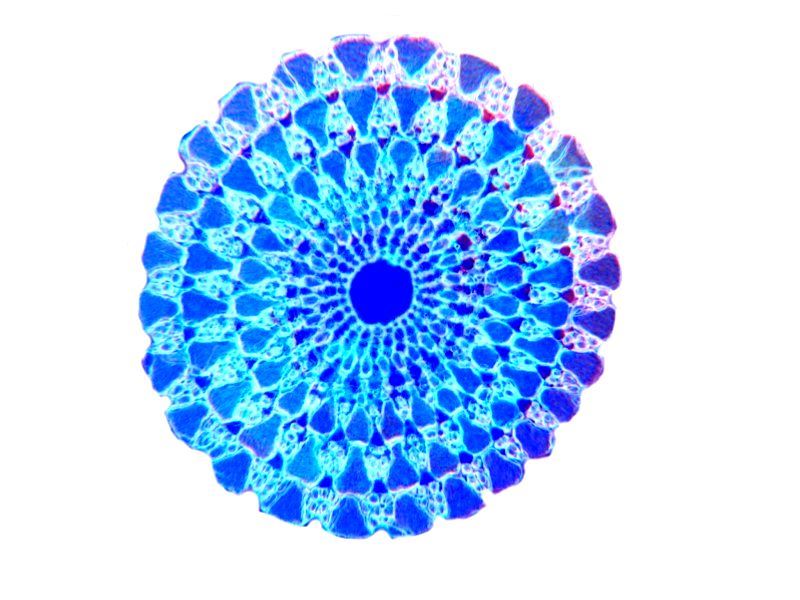

Let’s begin with a case that makes this point quite well–Aristolochia, also know as pipevine, Dutchman’s pipe, and birthwort. There are over 500 species. I have a 19th Century slide which gives no species designation. Let’s take a look at it beginning with a polarized view.

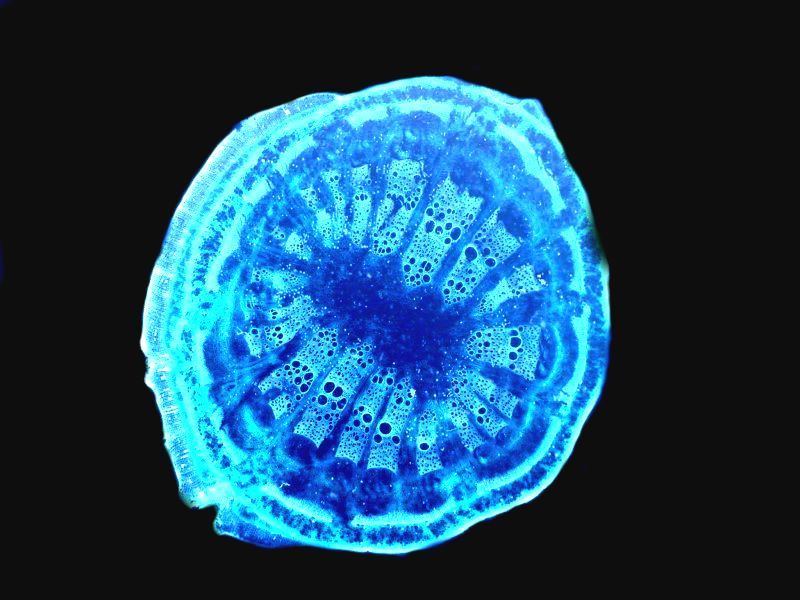

No surprise that it’s circular, but what might be a bit surprising is its resemblance to cross sections of sea urchin spines. If we apply the computer graphics invert function to the Aristolochia section, we have a quite a different view.

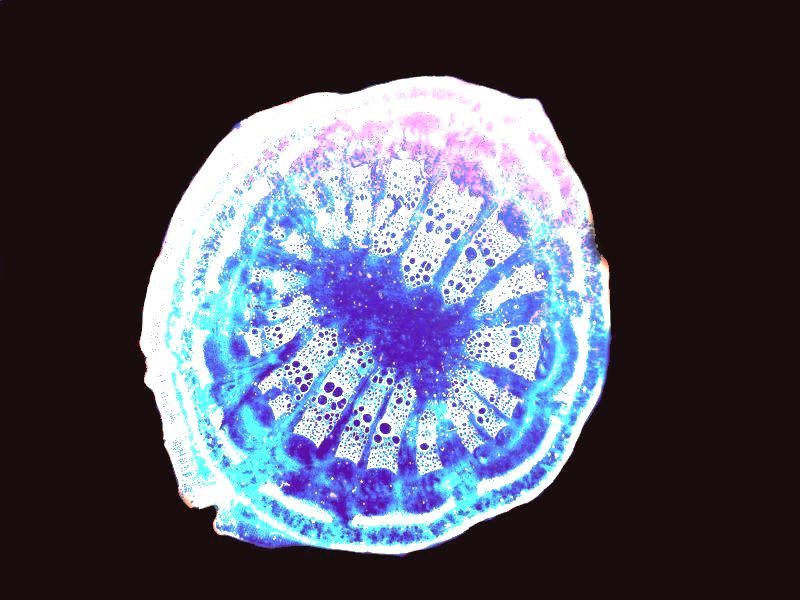

And here is yet another view using color contrast alteration on the inverted image to further heighten detail.

It turns out that Aristolochia has a long and interesting history in medicine and was used by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans and is part of traditional Chinese herbal medicine. It was used to treat a variety of maladies and also to help induce childbirth, thus its name “birthwort”. Side effects were noted early on, in all kinds of applications, but they were not given much emphasis–so much for the Hippocratic Oath (rather like today’s Pharmaceutical Oath–We Warned You.) Relatively recently, it has been discovered that Aristolochia is carcinogenic and can induce renal failure. Usually, at this point, I would launch into attacks on physicians, medical establishments, pharmaceutical companies, and corporate greed, but tonight I’m tired so I’ll abstain and spare you, but you get the idea–I’m not an enthusiast regarding those enterprises.

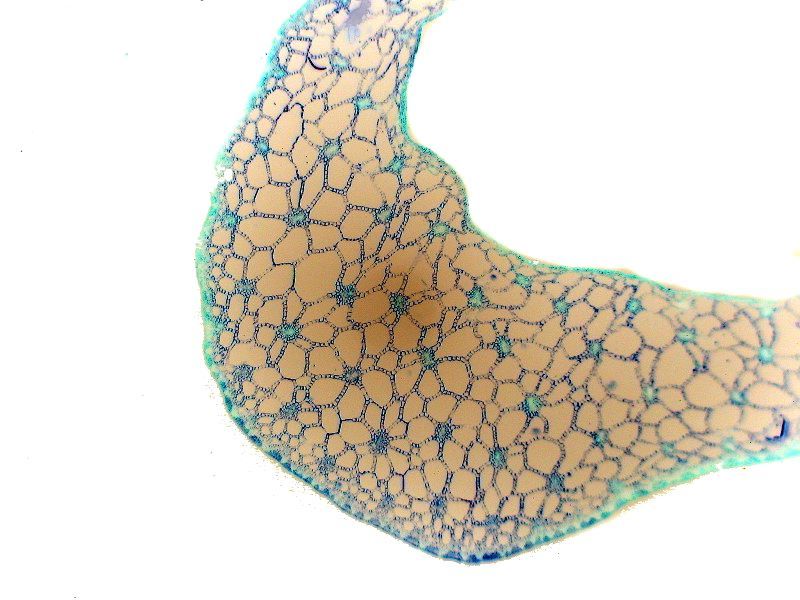

Next up is an apparently completely benign plant since, it seems no one has tried to use it medicinally. It’s called Botrychium and is a moonwort which is a type of fern. For some reason, the cross section looks rather spongy or squishy. From the outer “ring’, it is evident that it is packed with vessels for transporting fluid. I’ll show you a brightfield and an inverted image.

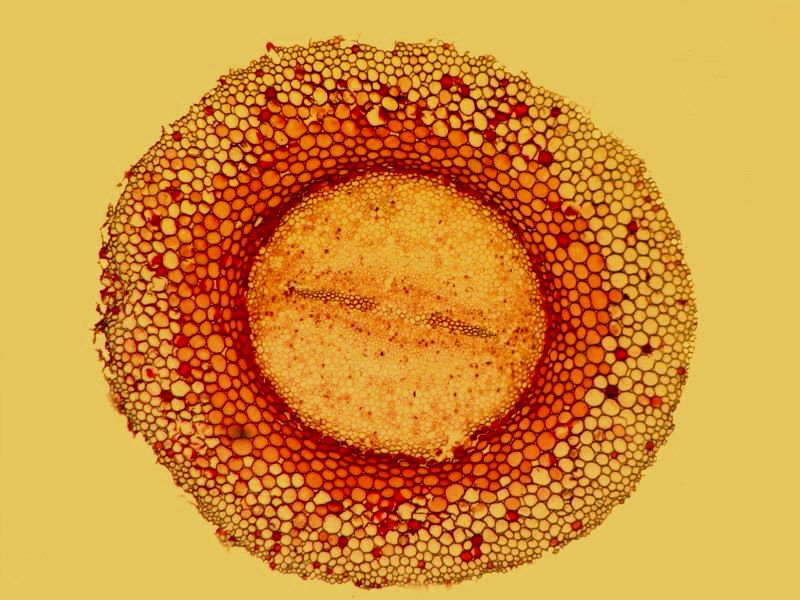

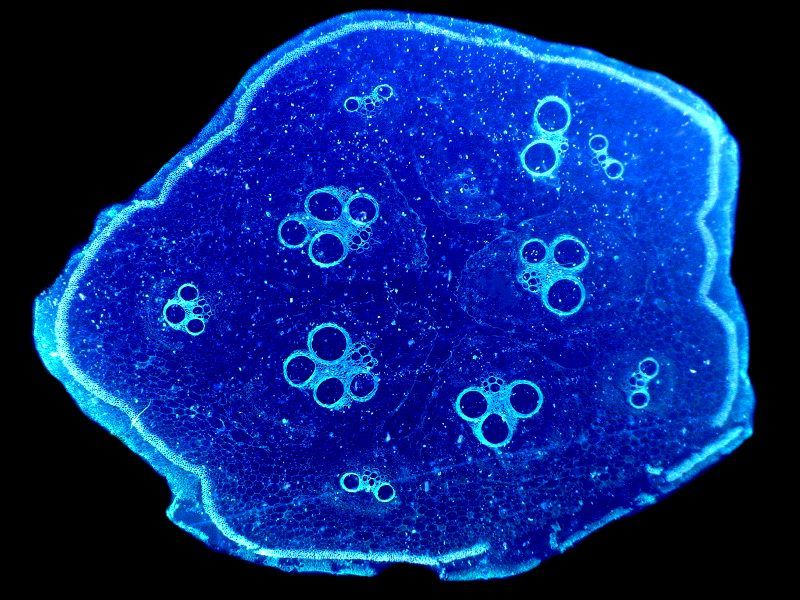

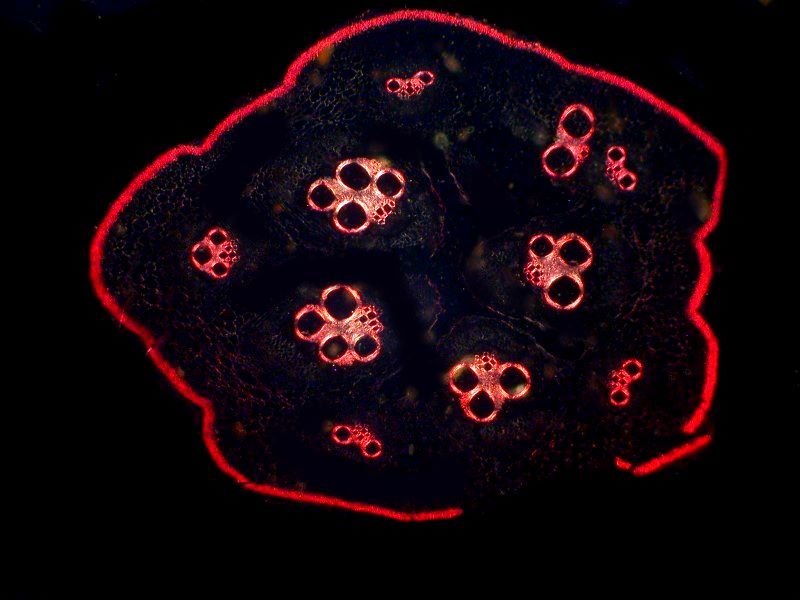

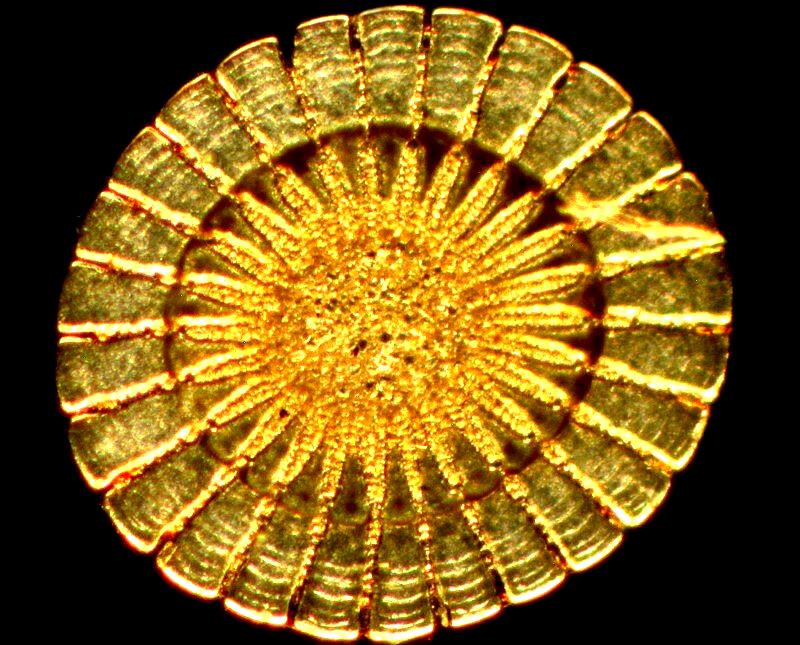

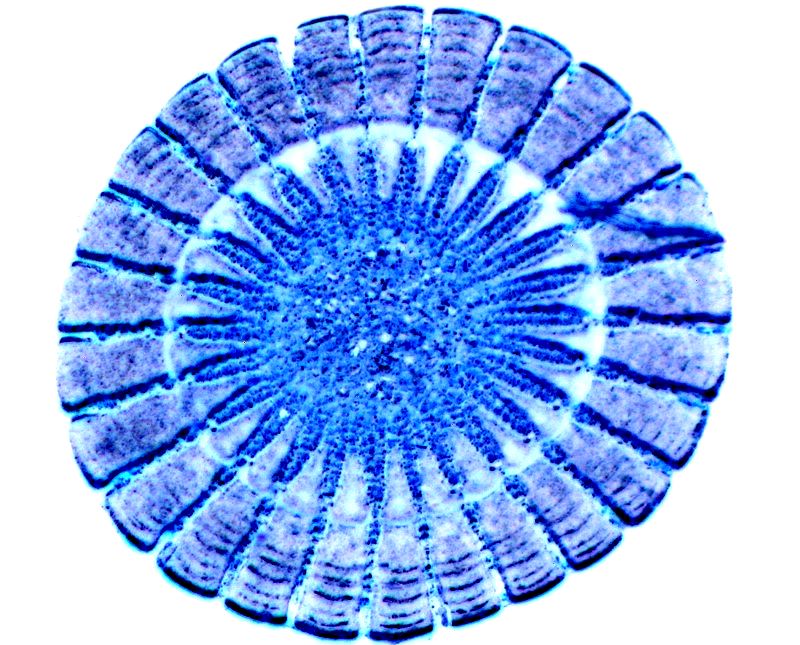

Gourds, squash, and pumpkins belong to the genus Cucurbita and produce some of the most colorful and delectable fruits for human pleasure both aesthetically and gastronomically. However, with a Victorian slide simply labeled Cucurbita sp., I can’t tell you what sort of lovely plant this might be, but I have a wonderful stem section which I will show you and I think you will agree that it is beautiful in its own right.

This is a brightfield image which shows clearly the transport vesicles. Amazing that a section over 100 years old can still impart such interesting information and in such a pleasing fashion.

Next, let’s look at the same section applying the invert function.

Here we get a virtually monochrome tinted image which is interesting.

However, in this case, the prize has to go to the polarized image which makes the vesicles jump out at us.

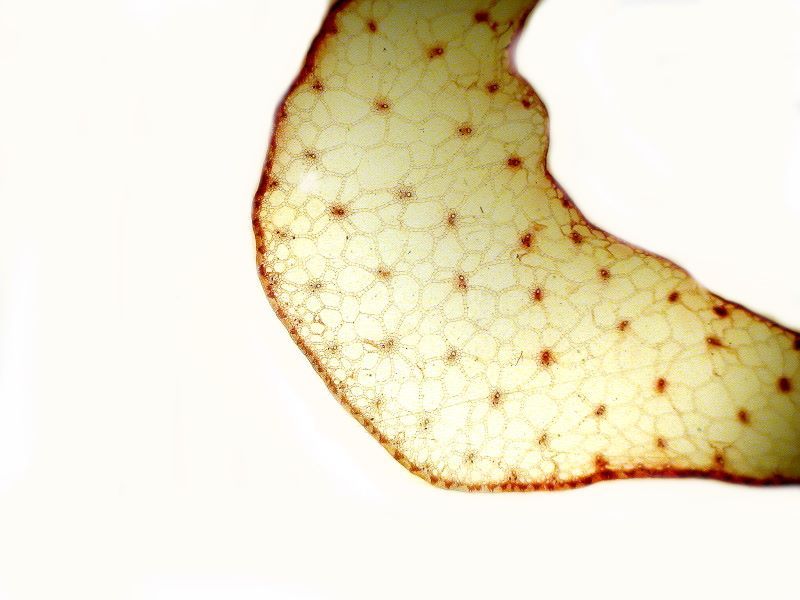

A very different sort of view is presented by a cross section of a sort of leaf, a pine needle. A brightfield view shows an odd-shaped form which reveals, in a rather vague fashion, a network between vesicles.

However, under polarized light the detail becomes much more evident.

And taking the polarized image and applying the invert function makes it even clearer yet.

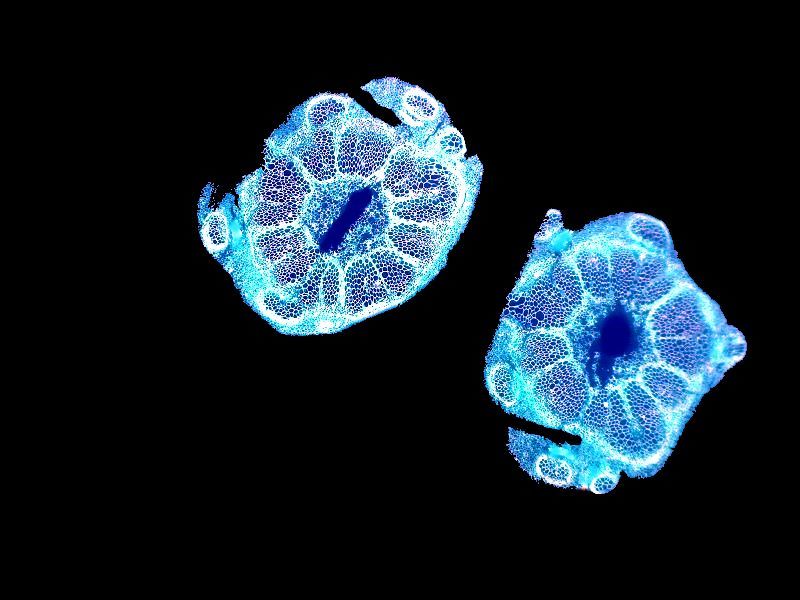

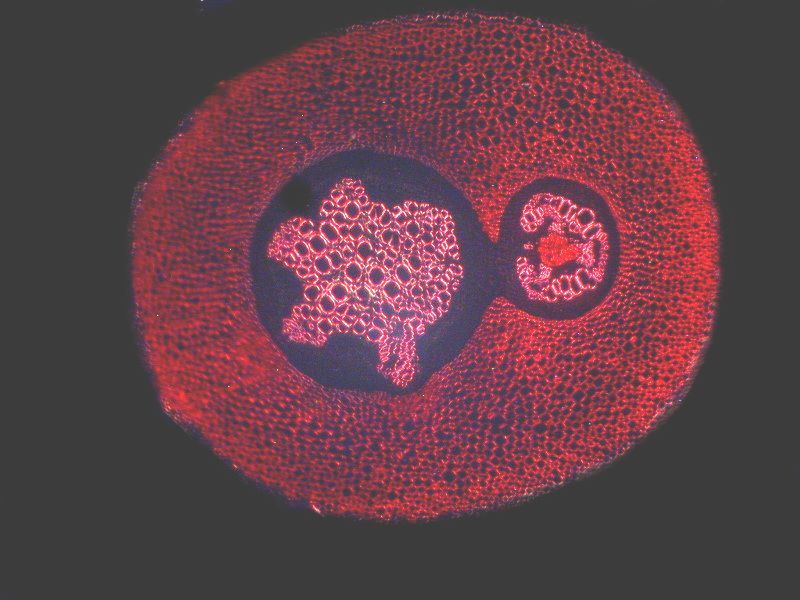

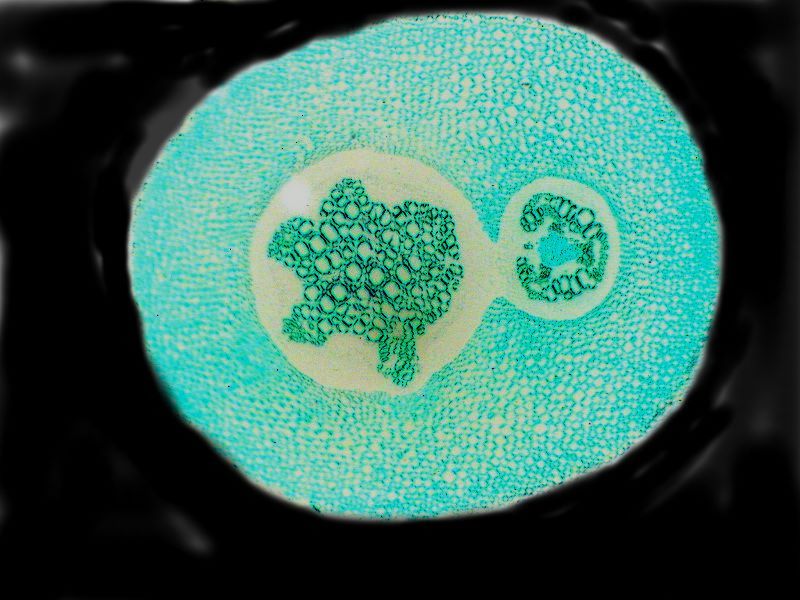

Sometimes, the shift from a brightfield image to a polarized one is startling. Part of a brightfield image can simply disappear in the polarized one. A dramatic example is this view of 2 stem cross sections of Osmunda, a temperate zone fern. This phenomenon raises some interesting and puzzling questions. The staining looks to be quite uniform as you can see.

However, when we look at the polarized images, significant portions simply disappear in the center and around the edges. Portions simply disappear both in the center and around the edges.

However, an inverted image with color contrast retains all the parts.

As Alice in Wonderland said, “Curiouser and curiouser.”

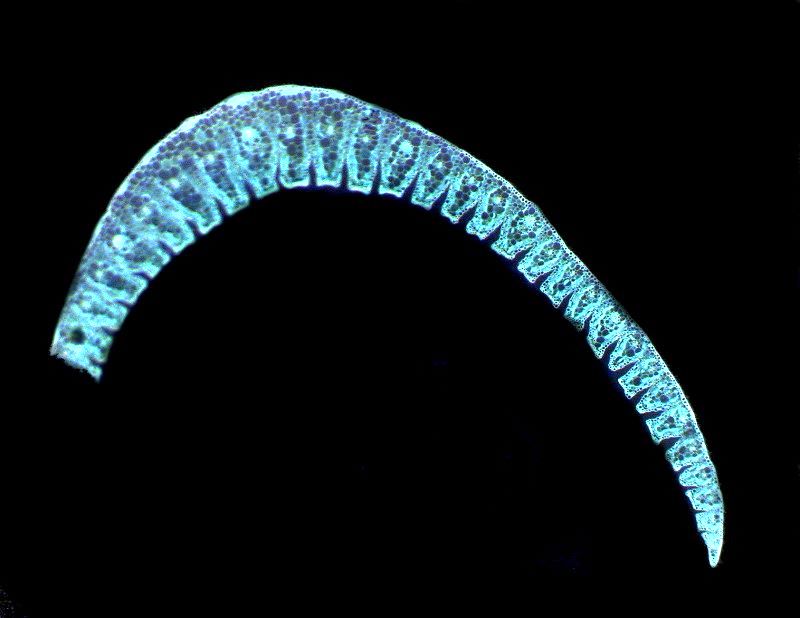

Previously we looked at a cross section of a pine needle and now, I’d like to look at another one from a different group, namely, the Larch of the genus Larix.

Again, we see the curved form that we would expect from the cross section of a pine needle. I’ll show 3 images all of which are, I think, distinctive. First, brightfield, then polarized, and then inverted polarization.

Interestingly, sometimes polarization shows no effect at all or one that is weak and not very informative whereas an inverted image with color contrast can be quite informative.

We get a nice illustration of this in a stem section of low mallow, so named because it grows close to the ground (not because of it’s lack of social status). It is from the genus Malva.

The brightfield image is clear, but not striking.

To my eye the polarized image is even less interesting.

However, surprisingly, the inverted, color contrast image is quite striking and shows detail one might well miss in the other 2 images.

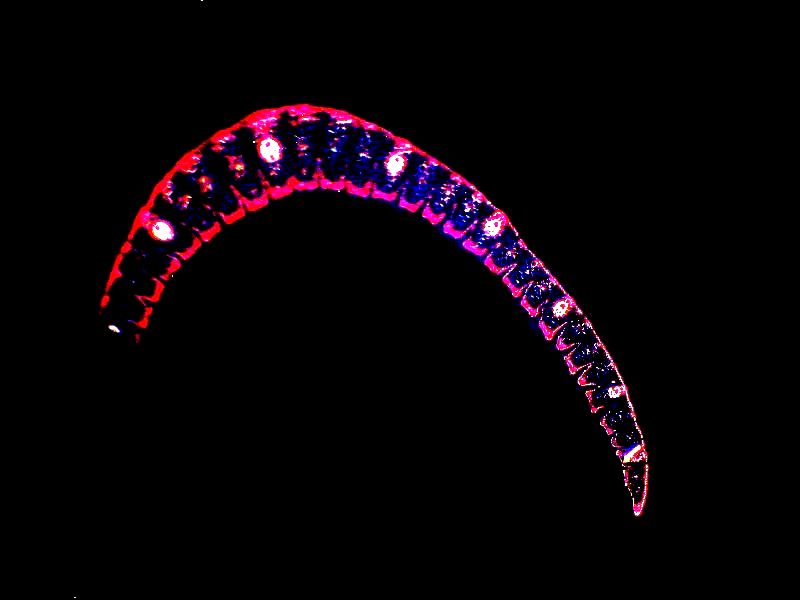

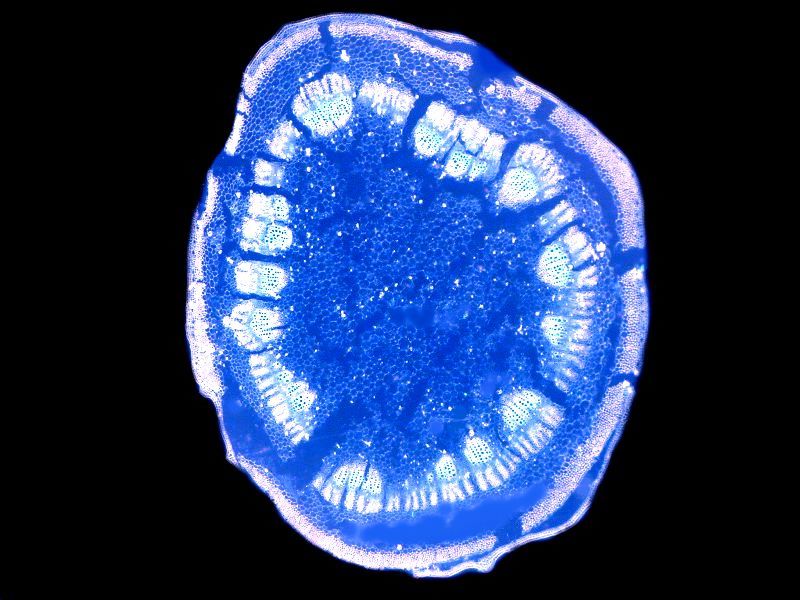

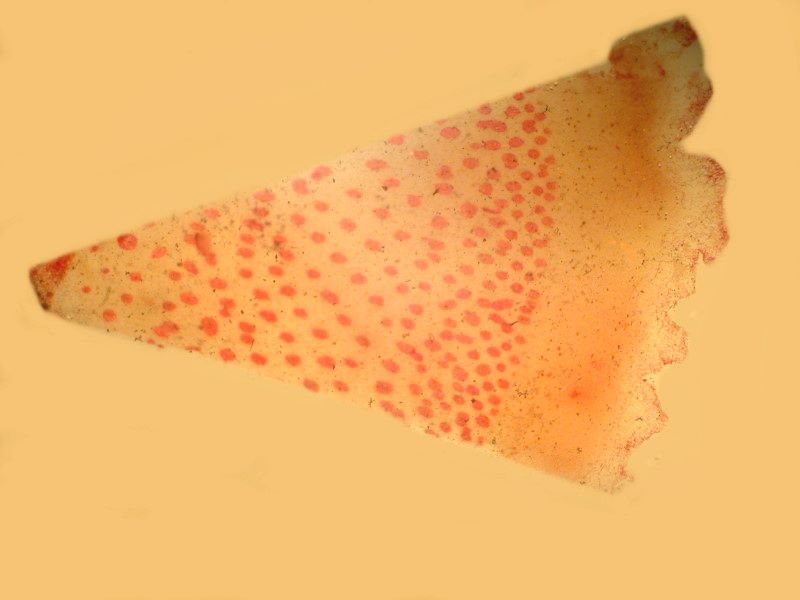

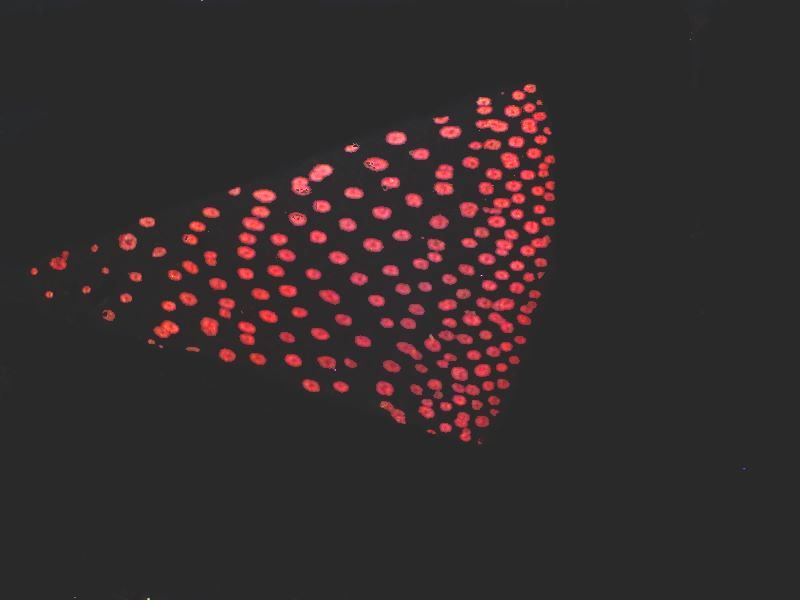

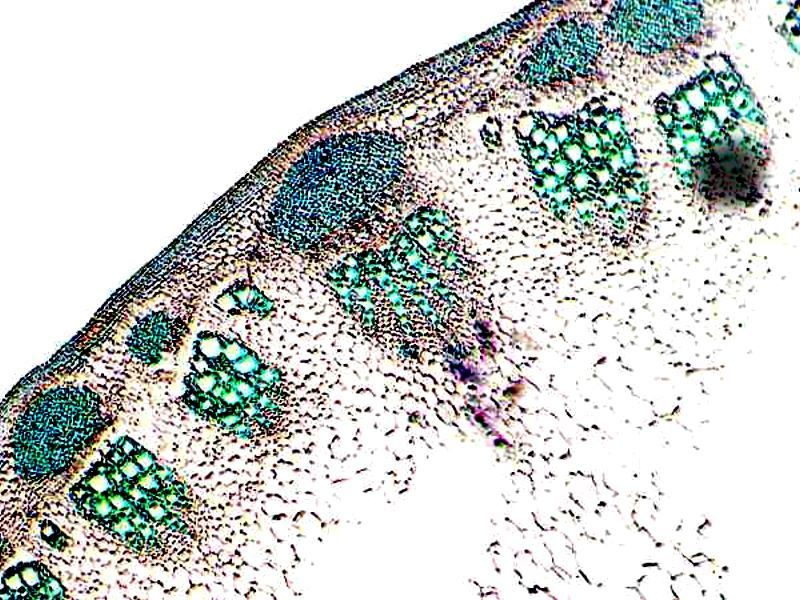

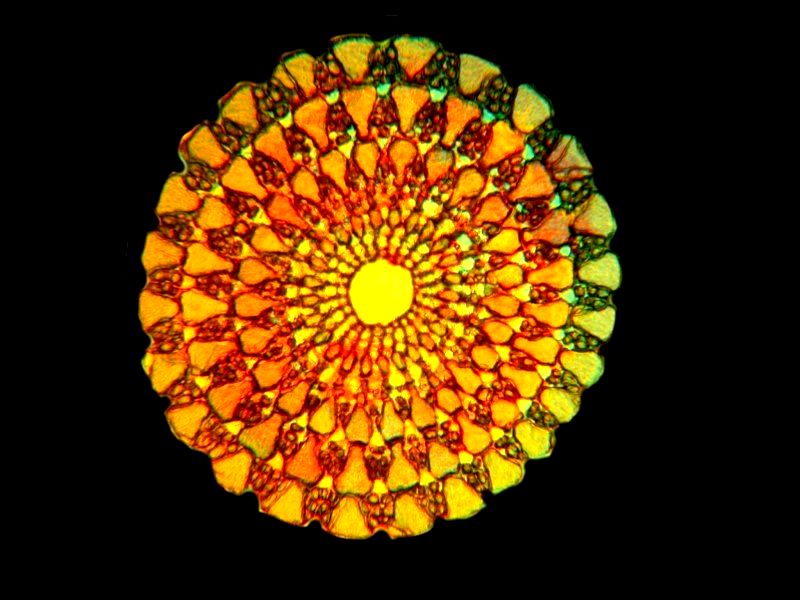

Perhaps you’d like a slice of Cordyline “pizza”. Cordyline is an evergreen shrub and, in this case, it’s unclear whether the person making the preparation cut a needle section or a triangular stem section.

Here once again, we see what wonders polarization can perform.

All those little red spots are micro-pepperoni.

I mentioned earlier in relation to Aristolochia that it looks very much like a cross section of a sea urchin spine. Surprisingly, this is true in quite a number of instances. Here is an image of a 19th Century stem section simply labeled “Citrus”. The image is polarized.

Another coniferous stem from Thuya certainly has a “woody” look, but also resembles an echinoid spine cross section.

Nature loves to repeat successful patterns, and toward the end of this album, we’ll take a closer look at the casual visual parallelism between some plant stems and some echinoid spine sections.

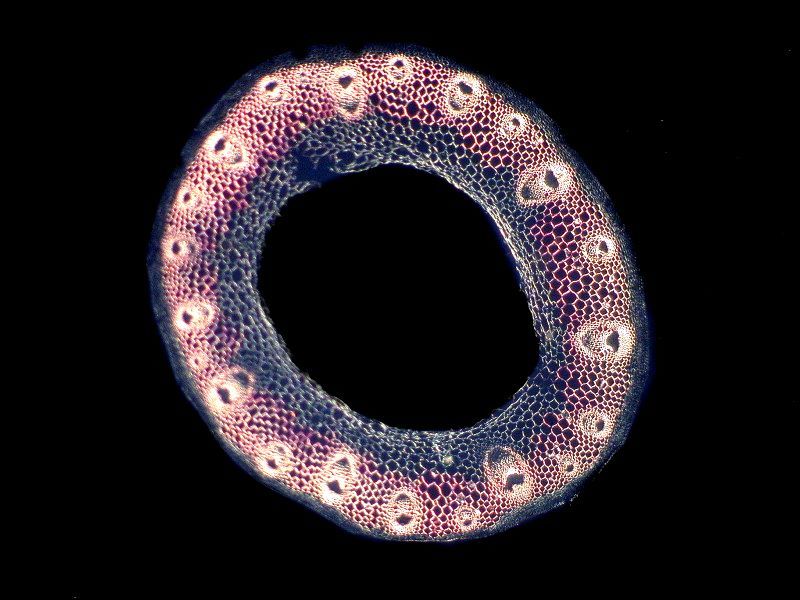

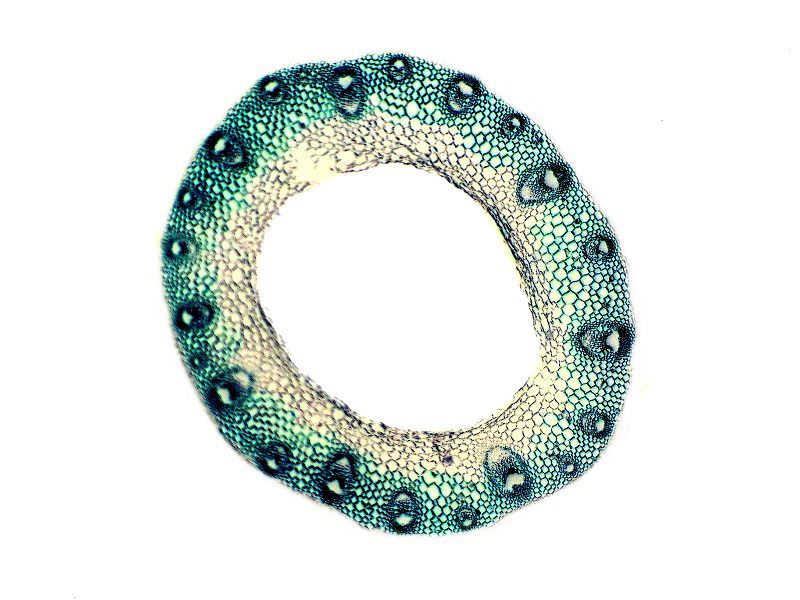

However, right now, I want to take a look at some interesting morphological oddities that are both intriguing and appealing. Let’s begin with Ranunculus or buttercup. Here all around the edge of the ring, we can see vascular bundles. First a polarized image and then an inversion of that image.

This look rather like a miniature life preserver ring.

Then there is the plant genus named after me, Richardia, well, O.K. maybe after Richard III. It’s also known as Mexican Clover. It’s quite unusual and we will look first at a polarized image and then at an inversion of that.

It rather reminds me of a dormant protist with captured prey which it is contentedly digesting.

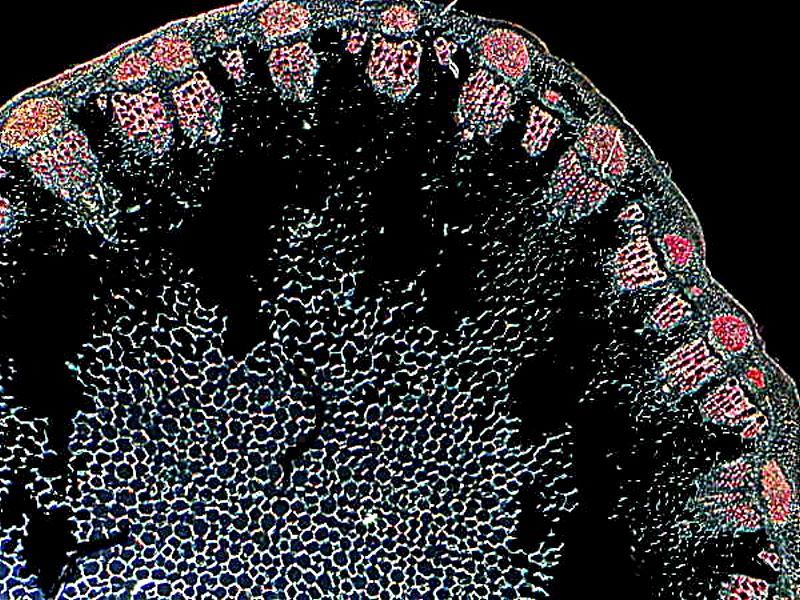

Sometimes one ends up with largish stems and one can only mange to get partial sections as is the case with a very nice old slide of a sunflower stem. First off, a polarized view of a large part of the section

And now the inverse of that image.

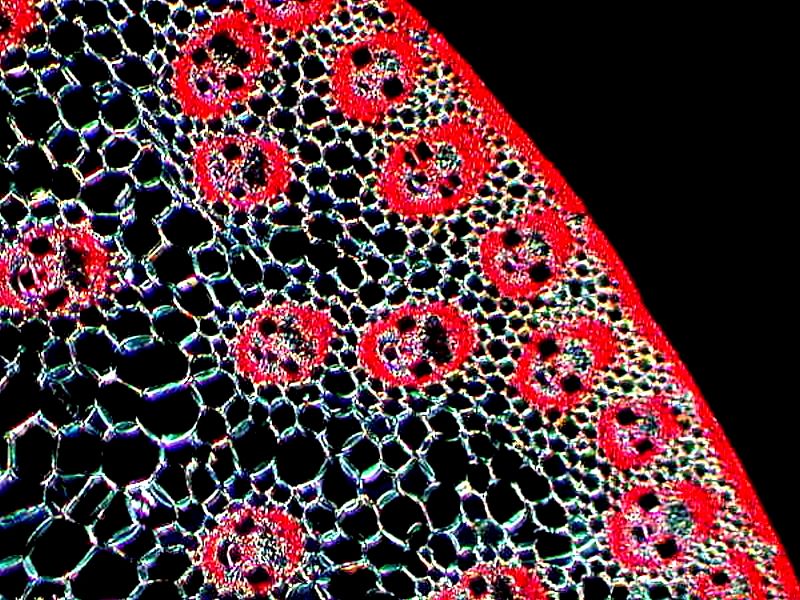

Next a polarized closeup along the edge of the section.

And here you begin to see the vascular bundles getting even more interesting.

With an even closer closeup, things get quite striking.

If we were to take the portion on the right, carve it in wood and stain it to fit the image, it could make a handsome tribal mask to hang on ones wall.

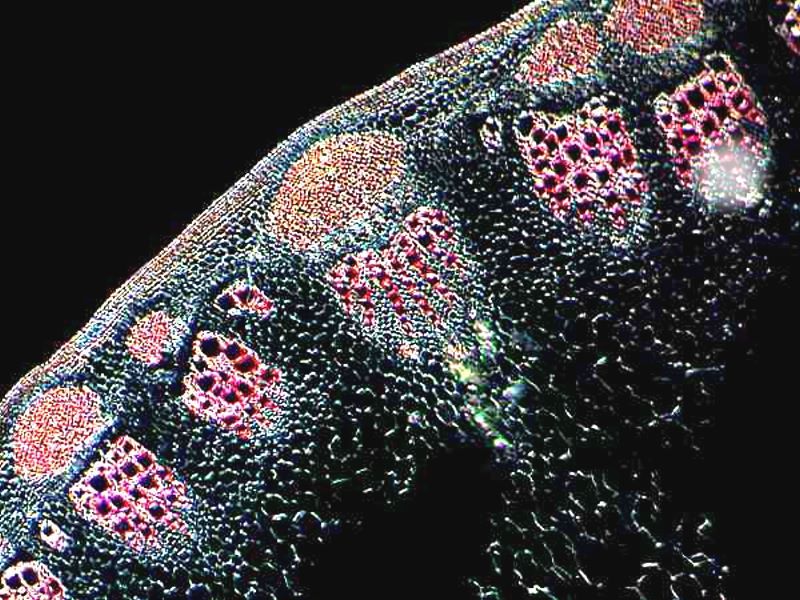

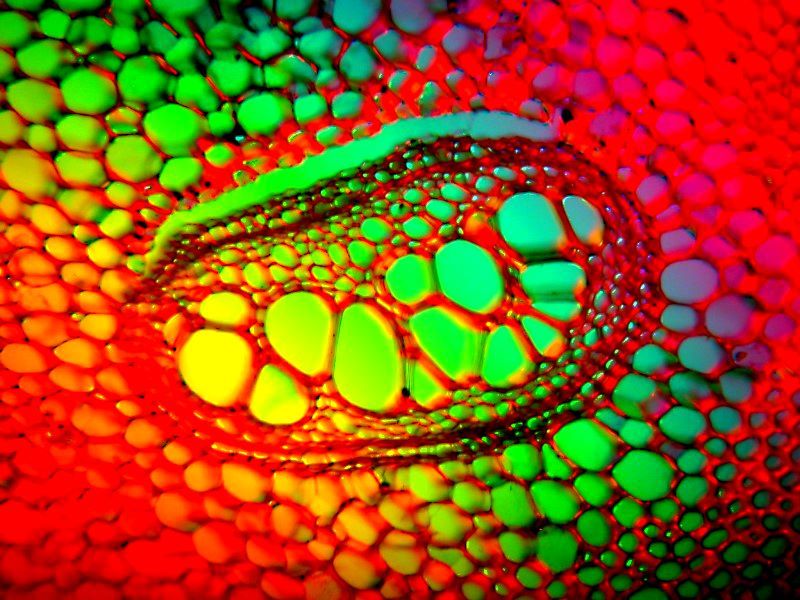

As you’ve probably guessed by now, vascular bundles are quite intriguing to me and in certain stems, such as the sunflower above, and the fern that we’ll be looking at next, they show up in a quite dazzling fashion. This section is from a fern of the genus Pteris of which there are some 300 species. The first was taken with Rheinberg illuminations showing one bundle and the second one, showing 2 bundles is also Rheinberg, but with the application of the invert function.

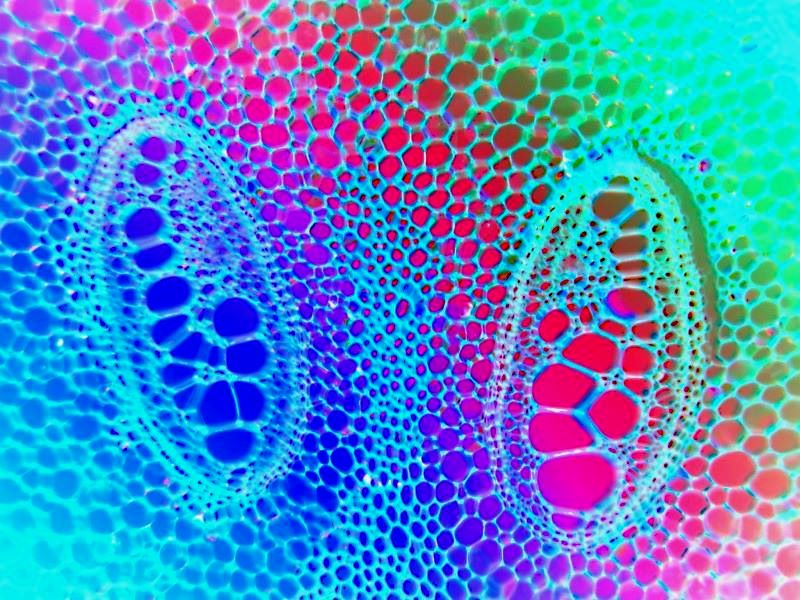

A cross section of corn (Zea mays) is also interesting for its vascular bundles. I’ll show 3 images; first polarization; second, invert; and third a closeup polarized.

By way of conclusion, let’s return to the issues of pattern parallelism. In the instances of echinoid spine cross sections, the open “tubes” are hollow areas between the calcareous crystals that constitute the spines. If they were solid, they would be too heavy for the sea urchin to move them adequately. So, the parallelism is by no means exact in detail but, nonetheless, unusually suggestive.

First, I will present you with a group of sections of plant stems and then finally a series of section of echinoid spines.

So, here are the plant stems.

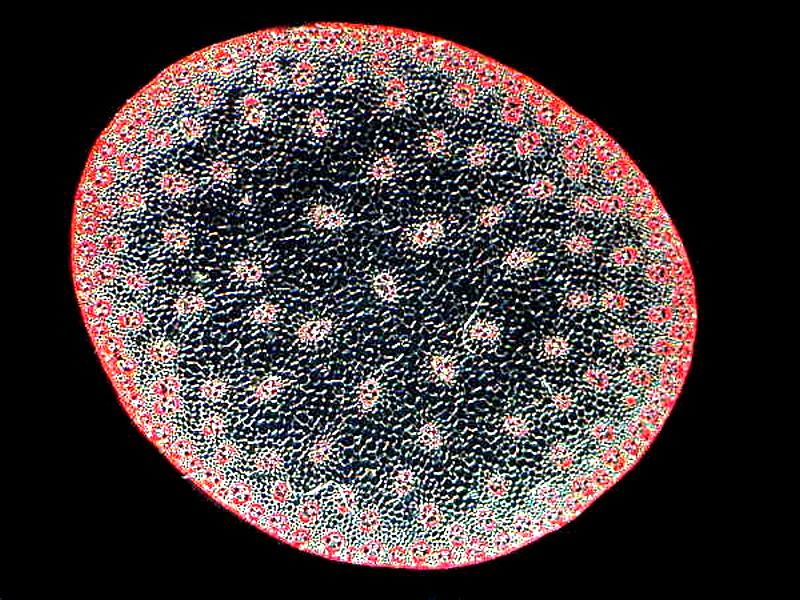

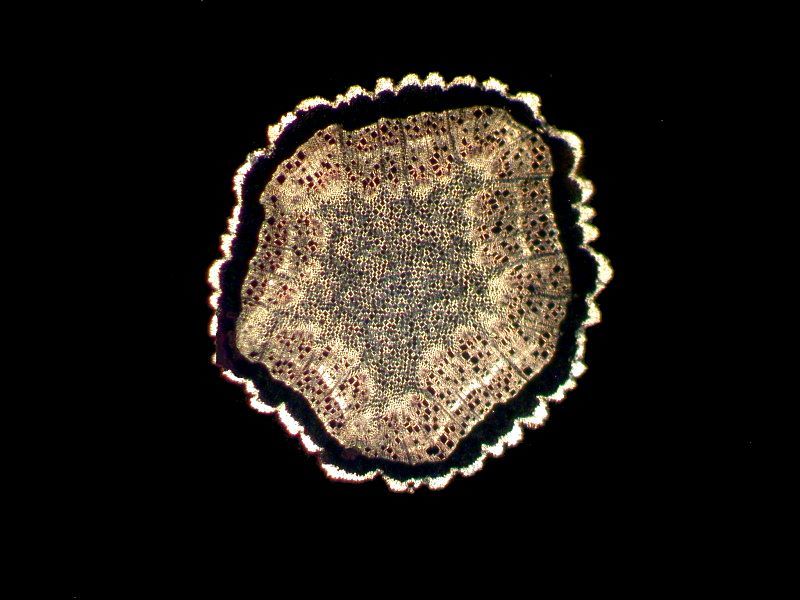

A pine section (Pinus). The irregularity around the edge can also be found in come echinoid spines.

Similax or Greenbrier, is mostly tropical and sub-tropical with about 350 species only 20 of which are found in the U.S. north of Mexico. The image is polarized.

Northern Red Oak. Querus rubra. Another pizza, anyone?

Joe-Pye or Eutochium named after a New England Indian who use these plants to treat a variety of ailments.

And now, here is a group of echinoid spine sections.

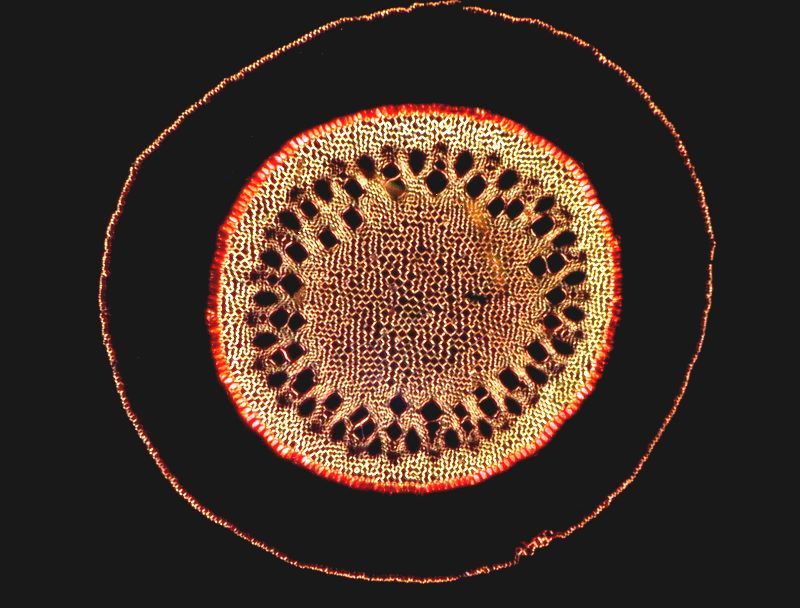

This first one looks rather like some ancient metal shield and the inverse image is quite lovely.

This next one perhaps displays that strongest resemblance to a plant section

The penultimate image shows crystals which are position rather like some of the vascular bundles in plant sections. They don’t have the same function, but there is still a certain visual similarity.

And finally, another lovely inverted image.

I just recently discovered another box of old slides which has a considerable number of stem sections and so it may well be that I will plague you with yet another such botanical album. I hope you enjoyed some of these images.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the February 2020 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .