|

|

A

Close-up View of the Wildflower

"Common Mullein"

(Verbascum thapsus)

by Brian Johnston (Canada)

|

PASTORAL

….

….

Oh, grey hill,

Where the grazing herd

Licks the purple blossom,

Crops the spiky weed!

Oh, stony pasture,

Where the tall mullein

Stands up so sturdy

On its little seed!

Edna St. Vincent Millay

This plant, with its very tall

flowering spike, is commonly found along roadsides, and in

fields. Mullein requires full sunlight in order to grow, and is

not found in shady locations. The spike can be very long,

sometimes reaching three metres above ground level. Able to

withstand the worst extremes of Canadian weather, most stalks remain

upright throughout the winter, projecting brown spikes up through the

snow. It is believed that these stalks provide refuge in their

deep crevices for over-wintering insects.

Common Mullein leaves, which are

oblong and stalkless, may be up to 40 centimetres long and 10

centimetres wide. They are densely hairy, and to the touch, feel

like thick felt. In fact, all parts of the plant, including stem

and flower petals share this soft texture. The dried down on

leaves and stem was used historically as tinder, since it ignited with

the smallest spark. Before cotton became the substance of choice

for lamp wicks, dried folded Mullein leaves were used for this

purpose. The old name “candlewick plant” originated from this

application.

Mullein is the sole member of the Figwort family in the province where

I live (Ontario). It is thought that the Latin genus name of the

plant, Verbascum

originated from a corruption of the word “barbascum” referring to

“barba”, meaning beard. (The shaggy foliage was thought to

resemble an unkempt beard.) The species name thapsus is

thought to refer to the ancient Greek city of Thapsos. The plant

has been given many common names over the years, including Flannel

Mullein, Flannel Plant, Feltwort, Velvet Dock and Jupiter’s Staff.

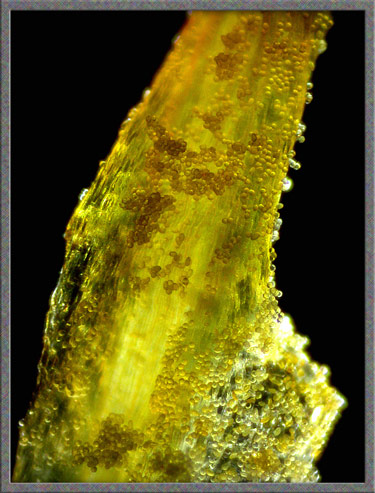

The first image in the article, and

the two below, show a typical flower-head. These structures are

usually from 20 to 40 centimetres long, and consist of a stem holding a

profusion of buds and blooms on extremely short stalks. Unlike

the flower-heads of many plants which bloom from bottom to top, or

vice-versa, Mullein’s bloom in a completely random fashion, with only a

few flowers being open at any one time.

A closer view reveals that some,

but not all of the filaments are completely enshrouded by long white

hairs. (I have not been able to find any information on the

purpose of these hairs, or why they are missing on some of the

filaments.)

The three images below show

close-ups of the reproductive structures - the five orange anthers and

single green stigma.

The following photograph shows

several unopened buds, and one which is about to open. The

flower’s petals are enclosed by hairy green bracts.

One of these bracts is shown below

at a higher magnification.

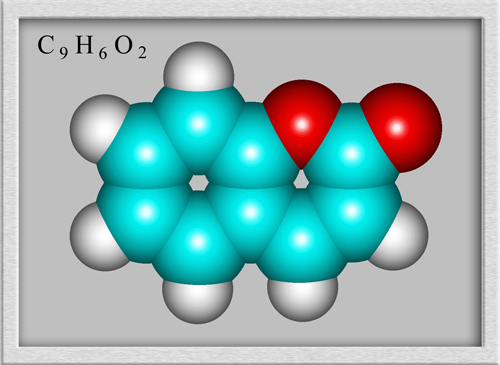

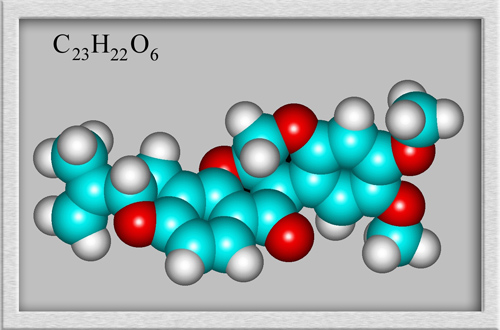

The green parts of the Mullein

plant contain small amounts of the chemical compounds coumarin and

rotenone. Coumarin

derivatives, (such as warfarin), are used as anticoagulants to prevent

undesirable clotting of the blood in patients suffering from heart

disease. The molecular structure of coumarin is shown below.

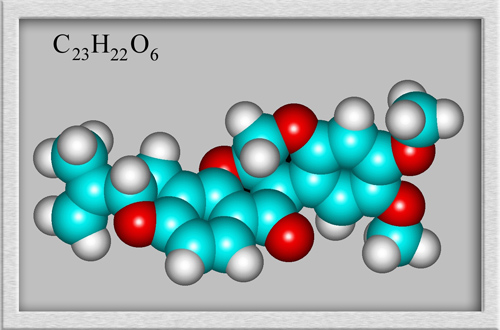

Rotenone

is a more complex molecule that acts as a broad-spectrum

insecticide. The compound works as a contact and stomach poison

by inhibiting cellular respiration. Rotenone is also used to kill

fish as a part of water body management. One such use is to

eradicate exotic fish from non-native habitats. The molecular

structure is shown below. (Both this, and the previous structure,

were produced using HyperChem.)

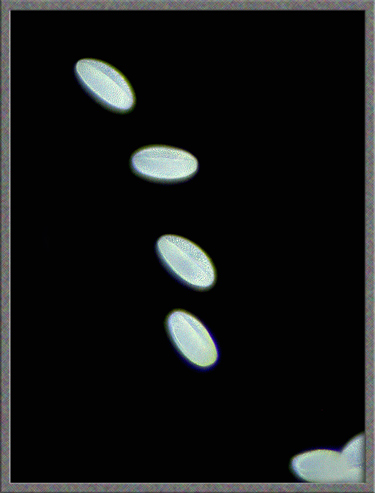

Pollen grains appear to be

ellipsoidal in shape and have two longitudinal grooves.

At the base of the style, there are

many hair-like projections with rounded ends. Several pollen

grains can be seen clinging to the surface of one.

The final image shows the irregular

surface of the stigma.

A Common Mullein plant produces a

huge number of seeds during the summer - up to 100, 000! These

seeds, it is said, can survive for almost a hundred years, until

conditions become favourable for their growth. It is no wonder

then, that the striking yellow-green spears are so prevalent in the

environment!

Photographic

Equipment

The photographs in the article were taken with an eight megapixel Sony

CyberShot DSC-F 828 equipped with achromatic close-up lenses (Nikon 5T,

6T, Sony VCL-M3358, and shorter focal length achromat) used singly or

in combination. The lenses screw into the 58 mm filter threads of the

camera lens. (These produce a magnification of from 0.5X to 10X

for a 4x6 inch image.) Still higher magnifications were obtained

by using a macro coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4

Olympus SLR lens to the F 828. (The magnification here is about

14X for a 4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz

SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix

4500.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

- Dickinson, Timothy, et al.

2004. The ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario. Royal

Ontario Museum & McClelland and Stewart Ltd, Toronto, Canada.

- Thieret, John W. et al.

National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers -

Eastern Region. 2002. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. (Chanticleer Press,

Inc. New York)

- Kershaw, Linda. 2002. Ontario

Wildflowers. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta,Canada.

- Royer, France and Dickinson,

Richard. 1999. Weeds of Canada. University of Alberta

Press and Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- Crockett, Lawrence, J.

2003. A Field Guide to Weeds (Based on Wildly Successful

Plants, 1977) Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. New York,

NY.

- Mathews, Schuyler F.

2003. A Field Guide to Wildflowers (Adapted from Field Book

of American Wildflowers, 1902), Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.

New York, NY.

- Barker, Joan.

2004. The Encyclopedia of North American Wildflowers.

Parragon Publishing, Bath, UK.

©

Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the

February 2006 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1996 onwards. All

rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk

with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .