Pollen tubes - this'll make your eyes water!

My interest in pollen was raised

when I read an article in October 1999 edition of Balsam Post

[1], the newsletter of the Postal

Microscopical Society. In

his article Chris Thomas explains the role of pollen, how to find

and observe it and, most fascinating of all, how to make it

germinate and grow pollen tubes. Chris himself has kindly given

some more details on the next page.

For a clear diagram of what happens

with pollen germination and syngamy when the pollen tube enters

an ovule see this link and for details of how to collect and mount

pollen grains see the booklet by John White [2].

My efforts at growing pollen tubes

started with various pollens on sugar solution. Success didn't

come until I tried Chris Thomas's method of spreading the pollen

on an onion epidermis laid on a moist microslide. Even this

hardly worked with our locally grown onions. However, a good big

Spanish onion produced instant success with a number of pollens

so that's the medium I use now. Leek epidermis is also successful

and has the merit of being curved about only one axis, so easier

to spread flat on a slide!

First you need a flower with ripe

anthers covered in pollen. A warm dry day is helpful for this.

|

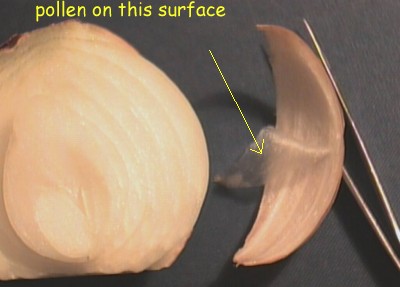

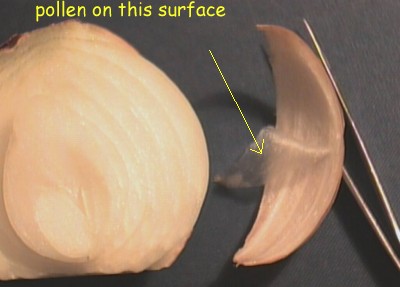

Where to get the epidermis? Cut the

top and bottom off an onion. With a sharp knife, cut a

few millimetres deep from the "North Pole" to

the "South Pole" of the onion. Now make a

similar cut so that the strip that you can remove is

about 15 mm wide in the middle. Remove this section from

the rest of the onion. Take a piece of epidermis from the

inside of the section - i.e. the concave surface

(scratching the edge with a finger nail or knife will get

it started and then you can peel it gently with fingers)

- and put it with the side that was towards the outside

of the onion upwards. |

Breathe on the slide to moisten it

just before you lay the onion epidermis on it and then gently

spread the skin to try to make a flat area about a centimetre

square. Don't worry if there are a few creases elsewhere.

Stroke the chosen ripe anther(s)

across this flat area and have a look under the microscope, using

a low power objective, to see that you actually have some pollen

grains on the onion skin. Label the slide with the name of the

flower, the date and time. I use waterproof ink (overhead

projector pens) direct onto the slide. Now place the slide in a

sandwich box or similar in which you have put a layer of damp

tissue and put the lid on to keep the air moist.

Periodically observe the slide and,

if there has been any growth, sketch or photograph the shape of

some of the tubes, noting the time on your picture. This will

permit you to work out the rate of growth of the tubes. In some

cases you will be able to see the tip of the tube moving if you

observe it under high power. I have found a 40x objective good

for this.

Of the pollens tried, the fraction

of pollen grains that germinated varied considerably. I started

this late in the year, so the variety of plants with pollen was

limited. Here is a rough guide to the activity that I found but

"your mileage may vary" (mine certainly does!):

| poor |

ivy |

field pansy |

| fair |

Penstemmon |

Nasturtium |

| good |

Japanese poppy |

dead-nettle |

.

Penstemmon (6 hours)

On the next page Chris has described his scoring system and

the details to record to make your observations of interest as

part of a collaborative project.

References:

1) Chris Thomas; "Balsam

Post", October 1999

2) John White; "Pollen, its Collection and Preparation for

the Microscope", 2nd edition, published by Northern

Biological Supplies Ltd. (£2.00)

Comments to the author John Garrett

are welcomed.

Email:antenna@btinternet.com.

©

Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published

in the December 1999 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please

report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is

the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

WIDTH=1

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights

reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net.