|

|

A

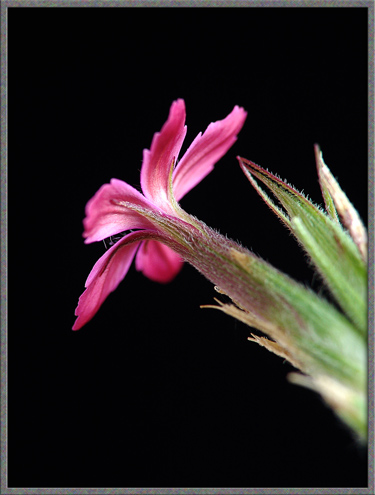

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Dianthus armeria) |

|

|

A

Close-up View of the Wildflower (Dianthus armeria) |

This

small, but brightly coloured wildflower was given its name due to the

fact that it was supposed to have grown in abundance during Tudor times

in the fields near Deptford UK, now an industrial section of

London. Although the population of Deptford Pink plants is

thought to be on the increase in Europe and North America, in the UK it

is in serious decline. In fact, the plant has an endangered

listing, and is therefore protected in many areas. I imagined

that “Pink” referred to the colour, however some sources say that it

relates to the serrated edge of each petal looking as though it was

trimmed by “pinking

shears”. The genus name Dianthus comes

from the Greek dios, meaning

“of Zeus” and anthos, meaning

“flower”, translating roughly to “flower

of the god(s)”. The species name armeria derives

from the Latin flos armeriae,

a type of flower.

The plants photographed for this article were growing in an open field

near a row of trees. The field was mowed infrequently, and the

plants would appear a couple of weeks after each cutting. This

limited their height to about 15 centimetres.

Deptford

Pink flowers grow in small clusters at the end of a thin stiff stem,

which can be from 15 to 25 centimetres high. Each approximately

one centimetre diameter flower has five petals with toothed edges, and

a sprinkling of small white spots. The light green leaves are

blade-shaped and often form V’s near the top of the plant.

Note

in the two images that follow, the five lance-shaped (lanceolate) greenish-brown bracts, (modified leaves)

immediately beneath the petals. These bracts tend to cover the tubular

base of the flower and prevent the flower’s trumpet shape from being

apparent. In addition, most plants have three narrow green

leaf-like bracts at the base of each flower.

A

flower has five stamens, each consisting of a pale filament holding aloft a purple or

red anther, (male pollen

producing structure). There are also two stigmas, (female pollen accepting

structures), although they are out of focus in the images below, and

are not visible.

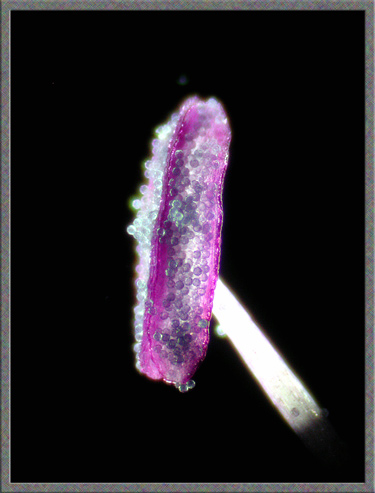

Under

the microscope a purple anther can be seen attached to its paler

rod-like filament. Several pollen grains are sticking to the

surface of the anther.

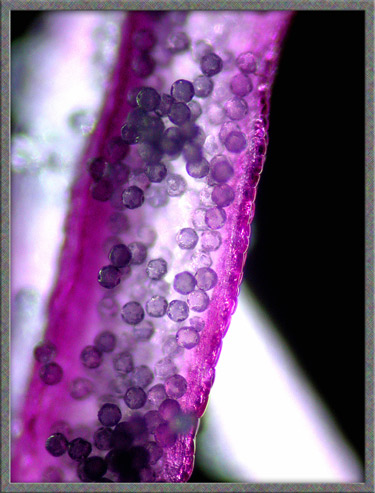

A

red anther is shown below. The higher magnification image on the

right shows many roughly spherical pollen grains.

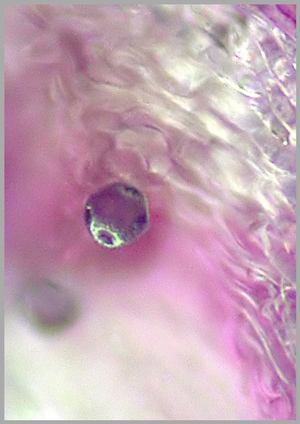

Notice

the single pollen grain at the centre of the image on the left

below. To the right is an enlargement of the grain revealing the

faceted shape, and the circular depression on each face.

Each Deptford Pink flower has two stigmas which project out a

considerable distance. This I suppose increases the chance of

fertilization by insect visitors. Each stigma is hairy, and tends

to be pink in colour at the tip. Notice also that the upper

bracts are striped in two shades of green, and are covered in fine

hairs.

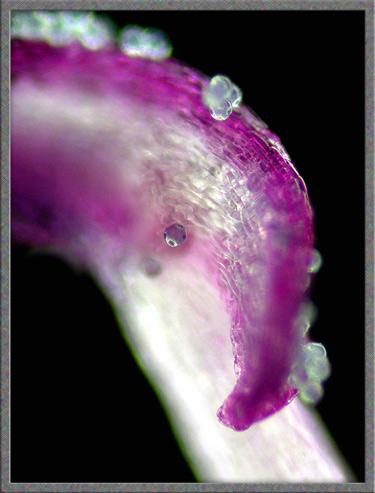

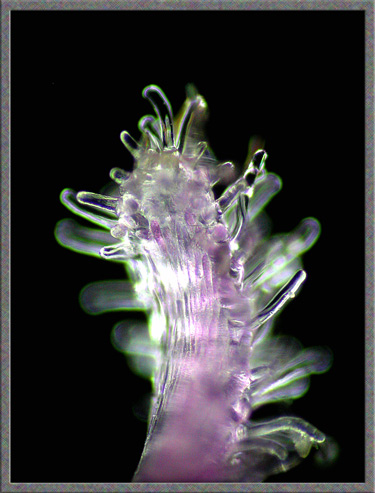

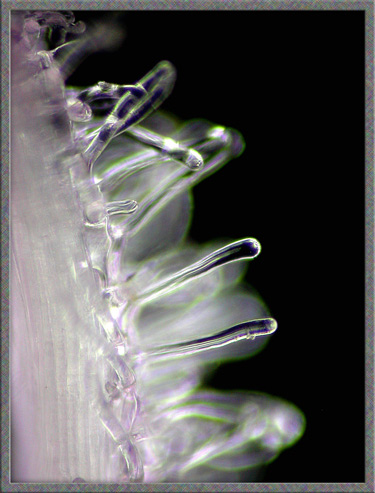

The

following two images show the almost transparent glandular protrusions

that encircle the stigma. These hairs ensure that any pollen

grains brought by visiting insects are retained by the stigma when the

insect leaves.

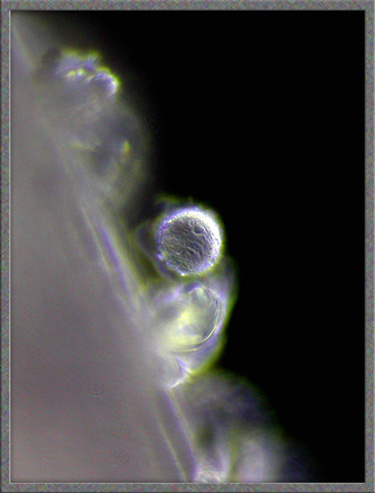

Some

of the surface detail on a pollen grain adhering to the stigma is

visible in the image below.

The

following photomicrograph illustrates the adherence of pollen grains to

the glandular stigma hairs.

While

examining a flower petal under the microscope, I was surprised to find

that at the centre of each white spot on the petal’s surface, there is

a single tiny hair growing perpendicular to the surface. (What, I

wonder is the purpose of these hairs?)

Before

blooming, a Deptford Pink plant has very grass-like leaves. This

makes identification very difficult until the plant blooms, revealing

the characteristic flowers. As the photograph shows, all surfaces

are covered with fine downy hairs. The higher magnification image

on the right shows a very immature bud, tinged with red.

The

fine hairs at the edge of a leaf are visible in the photomicrograph

below. On the right is an image of a hair like structure which

was growing from the base of one of the bracts.

Although

this diminutive member of the pink family can’t compete with its more

spectacular close relative the carnation, it nevertheless deserves

close study when one is lucky enough to find a specimen.

Photographic

Equipment

The photographs in the article were taken with an eight megapixel Sony

CyberShot DSC-F 828 equipped with achromatic close-up lenses (Nikon 5T,

6T, Sony VCL-M3358, and shorter focal length achromat) used singly or

in combination. The lenses screw into the 58 mm filter threads of the

camera lens. (These produce a magnification of from 0.5X to 10X

for a 4x6 inch image.) Still higher magnifications were obtained

by using a macro coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4

Olympus SLR lens to the F 828. (The magnification here is about

14X for a 4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz

SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix

4500.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

A Flower Garden of Macroscopic Delights

A complete graphical index of all

of my flower articles can be found here.

The Colourful World of

Chemical Crystals

A complete graphical index of all

of my crystal articles can be found here.

All comments to the author Brian Johnston are welcomed.

Published in the

December 2008 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1996 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .