THE WILD HONEYSUCKLE

Fair flower, that dost so comely

grow,

Hid in this silent, dull retreat,

Untouched thy homed blossoms blow,

Unseen thy little branches greet:

No roving foot shall crush thee

here,

No busy hand provoke a tear.

..................…

Philip Freneau

(1752-1832)

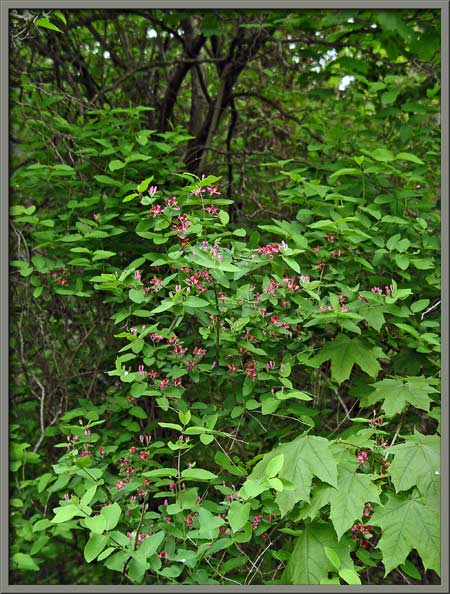

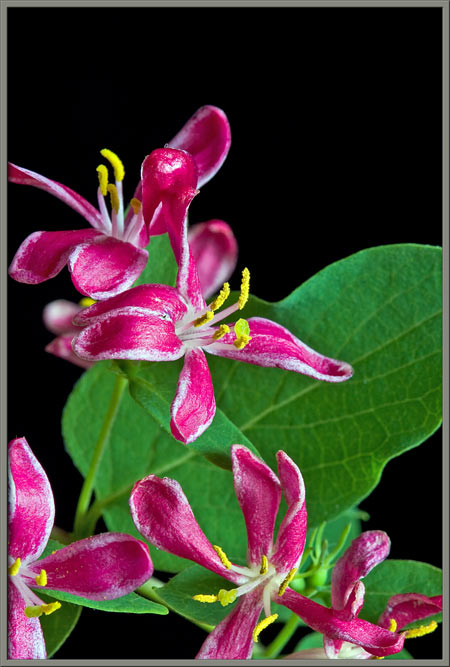

Honeysuckle bushes are a common

sight in southern Ontario where I live. Most have flowers in

shades of pink, but a few are white. About five metres from the

stream that passes through the area where I commonly search for

wildflowers, a single straggly bush, hidden from passersby by trees,

possesses the brilliant red blooms that can be seen above. I

suspect that the seed that grew into the mature plant was “dropped”,

(need I say more?), by a bird perched on a branch of the tree that

overhangs this particular bush. The fruit, that will be seen

later in the article, is a favourite food of birds, and small

mammals. The species is particularly cold tolerant, and thus

survives our extremely cold winters.

Tatarian honeysuckle is sometimes

referred to as ‘bush honeysuckle’, or ‘twinsisters’ (due to the fact

that the blooms occur in pairs at the end of a stem.) It

originated in Southern Russia and Turkistan, and was first introduced

into North America in the late eighteenth century. Honeysuckles

belong to the Caprifoliaceae

family. The name derives from the Latin caprifolium which roughly

translates to “goat’s leaf”. (Honeysuckle leaves were a favourite

food of goats.)

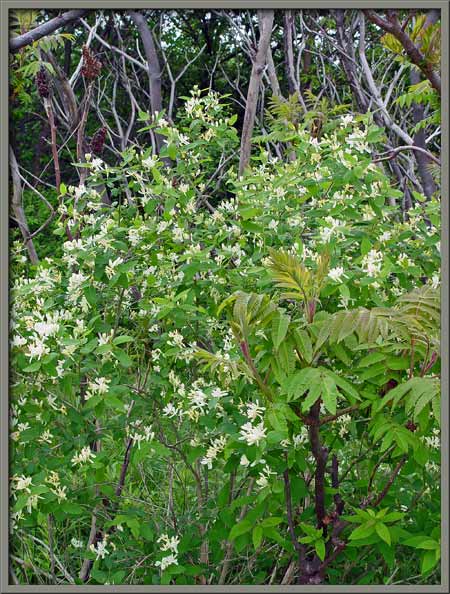

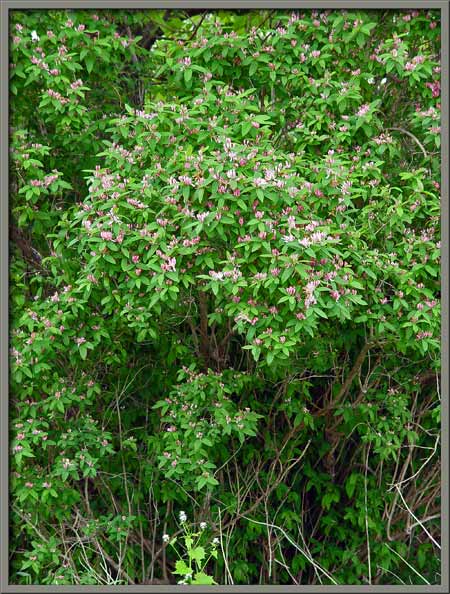

As can be seen below, the bush from

which the flowers were obtained, is almost completely surrounded by

trees and saplings.

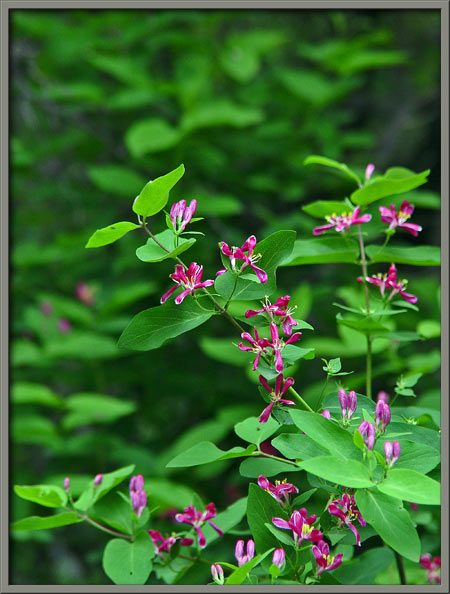

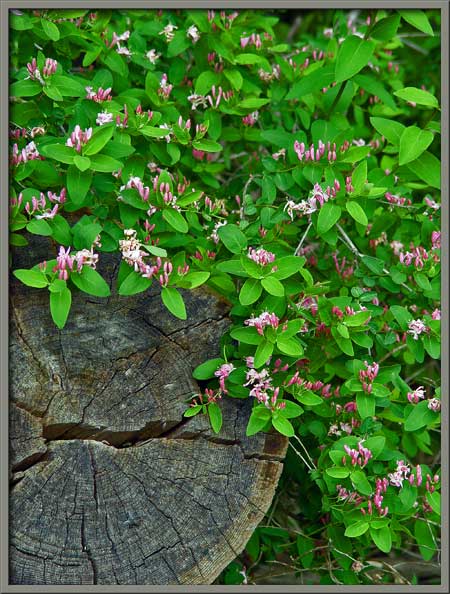

Notice in the image at right below,

that the oval leaves are arranged opposite one another, and that the

stems supporting the pairs of flowers grow from the points of

intersection of the leaves to the stem, (the “axils”).

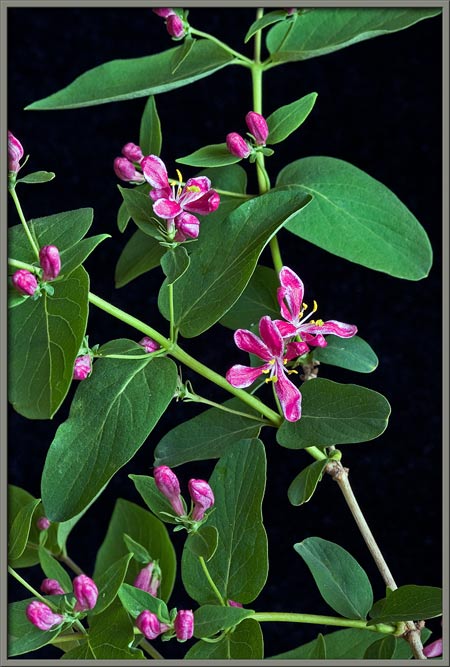

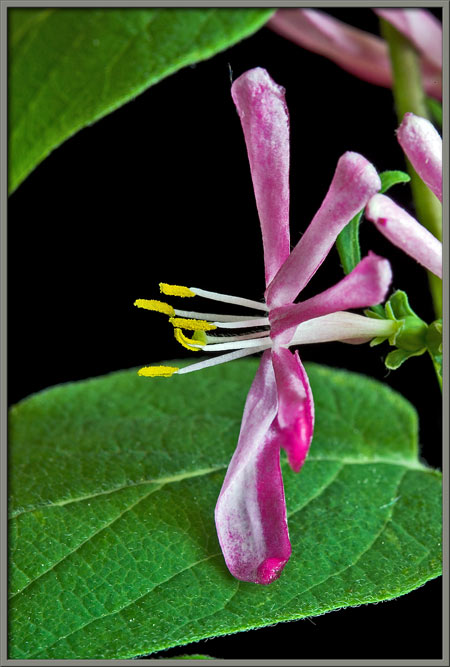

Beneath each pair of buds there are

two leaflets. Immediately above the leaflets, there are two sepals

(modified leaves) that partially cover each of the green, egg-shaped,

immature ovaries. At the top of each ovary is a ring of very tiny

pointed, green, sepal-like structures. Notice in the image at

right, that the bottom surfaces of the lower-most leaflets are covered

with small hairs.

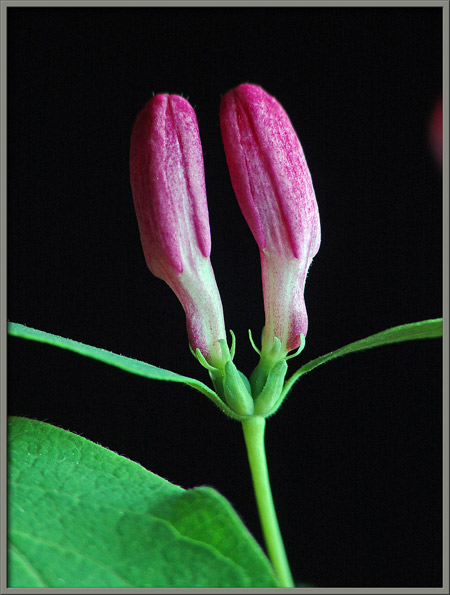

The bud itself has an elongated

red, bulbous top, and white tubular bottom. It is just possible

to discern the individual petals of the flower making up the topmost

section of a bud.

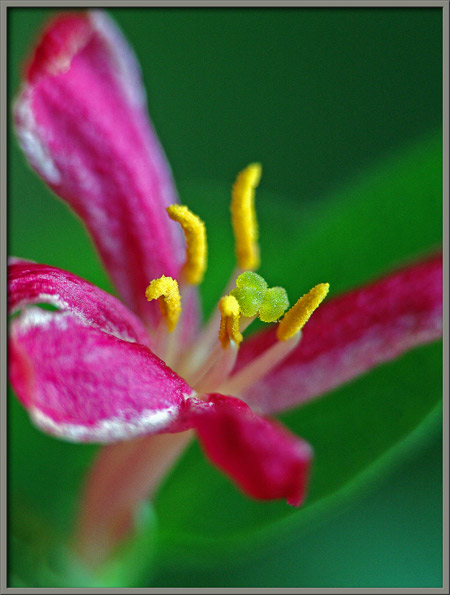

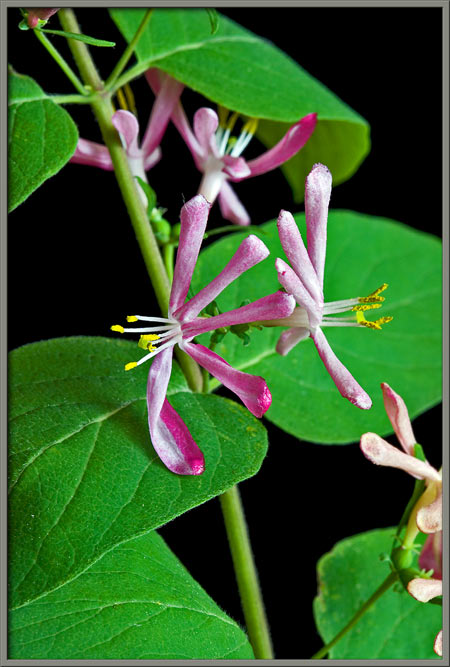

A mature flower possesses five

spoon-shaped, brilliant red petals. Notice that the edge of each

petal is white.

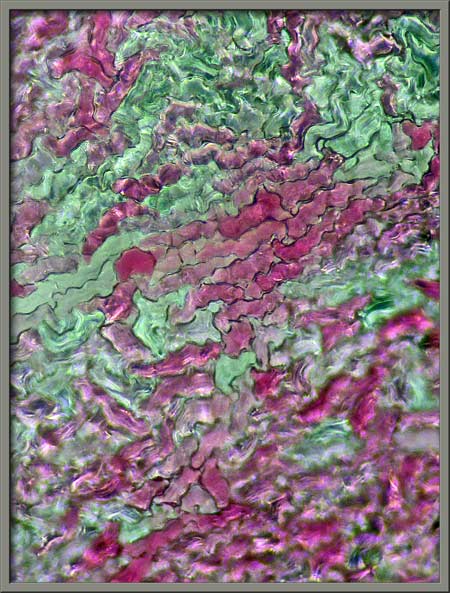

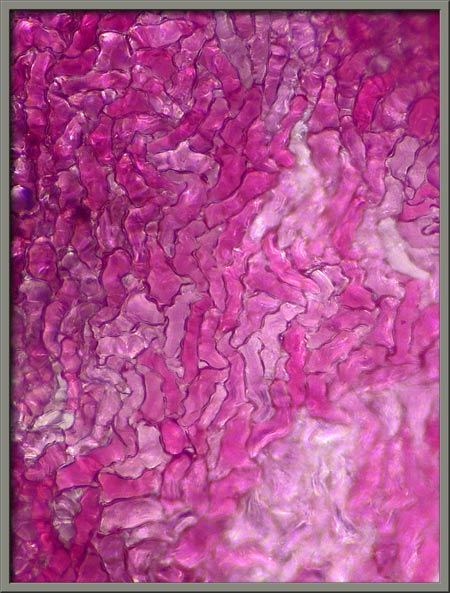

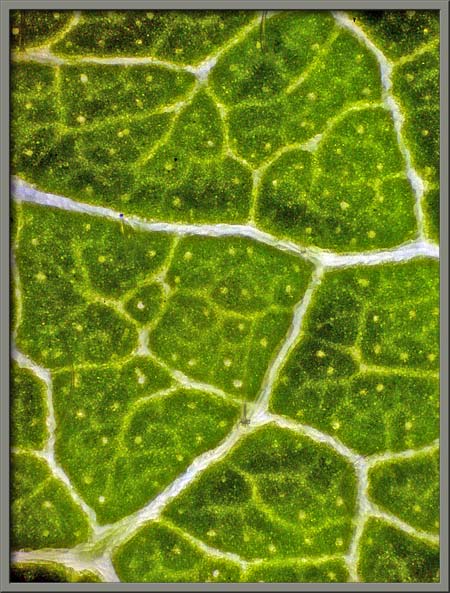

If one of the areas of intermediate

colour is examined under the microscope, its cellular structure becomes

visible.

The photomicrograph on the left

below shows that the white areas of the petal are composed of cells

with no red pigment, while that on the right shows an area where the

colour is deep red due to cells containing varying amounts of red

pigment.

Tatarian honeysuckle’s reproductive

system consists of five bright yellow anthers

(male pollen producing organs) supported by white filaments, and a central, bulbous,

green stigma (female pollen

accepting organ) supported by a white style.

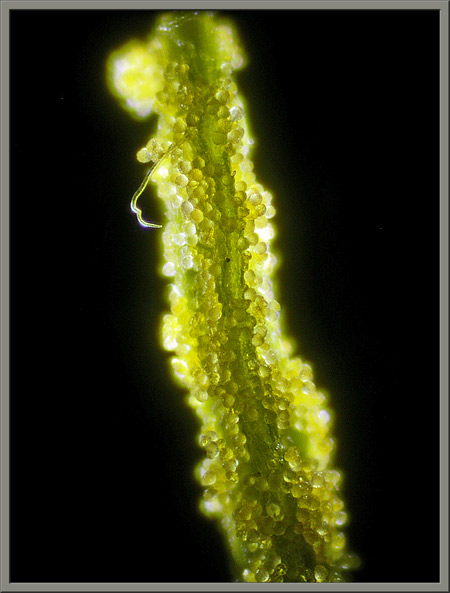

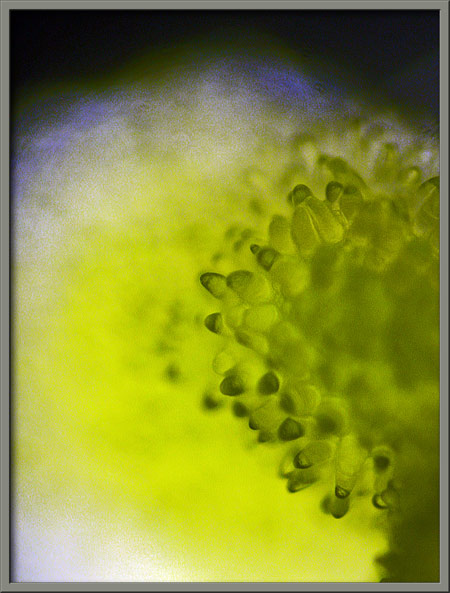

Under the microscope, an anther’s

coating of spherical pollen grains is visible.

Higher magnifications reveal the

roughly spiked surface of each grain.

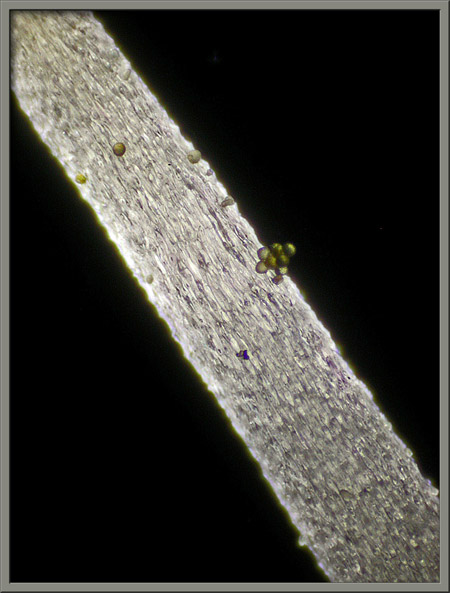

Some pollen grains adhere to a

filament’s surface.

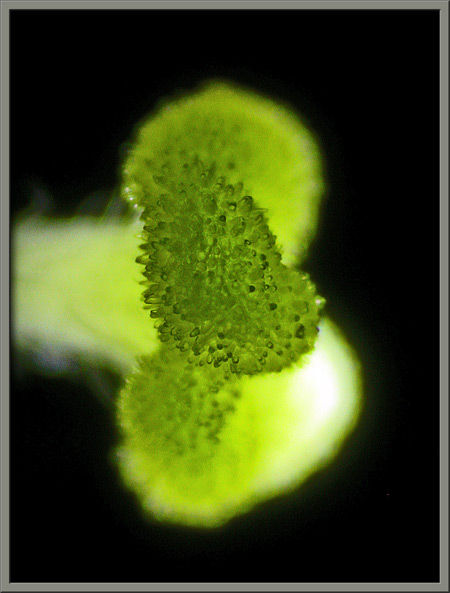

Close examination of the flower’s

green stigma reveals that it is divided into three ellipsoidal

lobes. The photomicrograph on the right shows the rough surface

structure of one of the lobes.

Higher magnifications show that a

lobe’s surface is covered with short, rounded protuberances that aid in

the collection and retention of pollen grains transferred to the flower

by insects acquiring the nectar stored at its base.

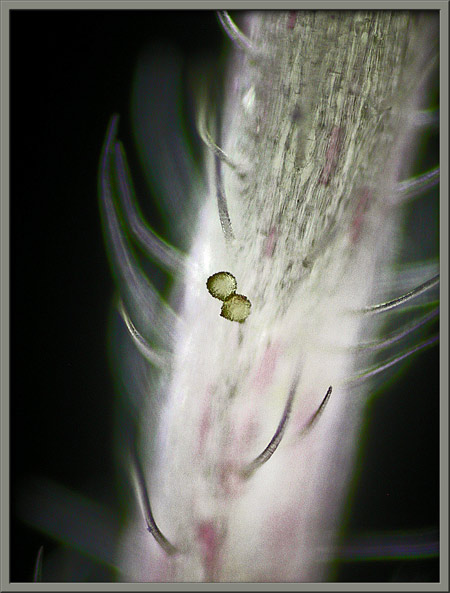

Unlike the filament, the style

supporting the stigma is covered with long hairs. The image on

the right shows a couple of pollen grains stuck to one of the hairs.

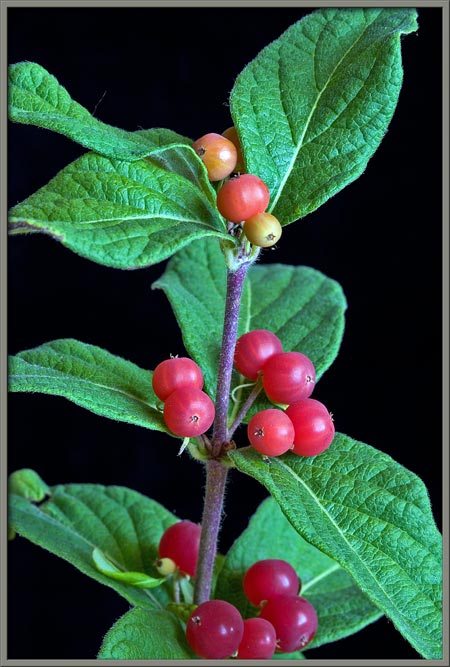

When a flower has been pollinated

(by having pollen deposited on its stigma), a pollen grain germinates

and sends a root-like tube down though the style to the flower’s

ovary. The grain’s male sex germ travels down the tube to an

ovule in the ovary where the female sex germ is located.

Fertilization occurs when the two sex germs combine. After

fertilization, the flower’s fruit, (or in this case two fruit) begin to

develop. The image below shows two such fruit with the brown

remnants of the flowers’ pistils still visible.

Notice the veined surface of the

leaf seen in the image above. In the lower magnification image at

left below, the intricate vein structure at the edge of a leaf can be

seen. The image on the right shows a higher magnification view of

one of the principal veins on the underside of the same leaf.

Note the many long hairs that grow out from this central vein.

Still higher magnifications show

the hairs more clearly.

By mid July, the many fruit pairs

provide the honeysuckle bush branches with a touch of brilliant

colour. Note at the top of the two images, that a fruit

transforms from green, through yellow and orange, to its final red

colouration.

The abundant fruit of a tatarian

honeysuckle bush are visually striking, and much prized by birds as

food.

Earlier in the article I mentioned

that Tatarian honeysuckle can produce flowers of other colours.

Some distance from the stream, there are several white bushes.

These flowers are identical to the

earlier ones, in all but colouration.

Pink honeysuckle flowers are the

most common. Two typical examples of bushes can be seen below.

Once again, only the flower colour

is different.

Notice the similarity of the

reproductive structures to those seen earlier.

Tatarian honeysuckle readily

invades old fields, open woodlands, and other disturbed sites. It

sometimes forms a dense thicket that can restrict native plant

growth. For this reason some jurisdictions consider it to

be an undesirable plant. Where I live however, this is certainly

not the case. Its colourful flowers and fruit are a welcome sight

to any passerby.

Photographic Equipment

Most of the photographs in the

article were taken with an eight megapixel Canon 20D DSLR and Canon EF

100 mm f 2.8 Macro lens. An eight megapixel Sony CyberShot DSC-F

828 equipped with achromatic close-up lenses (Canon 250D, Nikon 6T, and

Sony VCL-M3358 used singly, or in combination), was used to take a few

of the images.

The photomicrographs were taken

with a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the

Coolpix 4500.

References

The following references have been

found to be valuable in the identification of wildflowers, and they are

also a good source of information about them.

Dickinson, Timothy, et al. 2004.

The ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario. Royal Ontario

Museum & McClelland and Stewart Ltd, Toronto, Canada.

Thieret, John W. et al. National

Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers - Eastern

Region. 2002. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. (Chanticleer Press, Inc. New

York)

Little, Elbert L. National Audubon

Society Field Guide to North American Trees - Eastern Region.

2004. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. (Chanticleer Press, Inc. New York)

Kershaw, Linda. 2002. Ontario

Wildflowers. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta,Canada.

Royer, France and Dickinson,

Richard. 1999. Weeds of Canada. University of Alberta

Press and Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Crockett, Lawrence, J. 2003.

A Field Guide to Weeds (Based on Wildly Successful Plants,

1977) Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. New York, NY.

Mathews, Schuyler F.

2003. A Field Guide to Wildflowers (Adapted from Field Book

of American Wildflowers, 1902), Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.

New York, NY.

Barker, Joan. 2004. The

Encyclopedia of North American Wildflowers. Parragon Publishing,

Bath, UK.