|

|

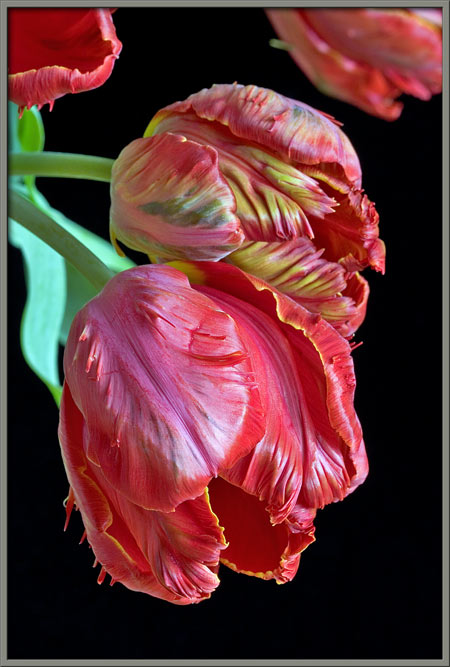

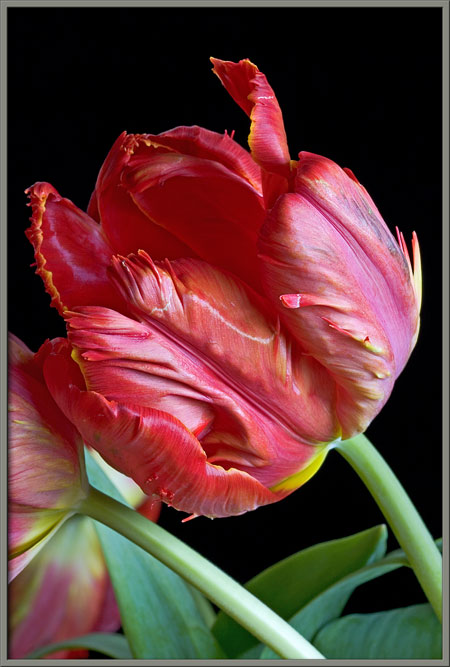

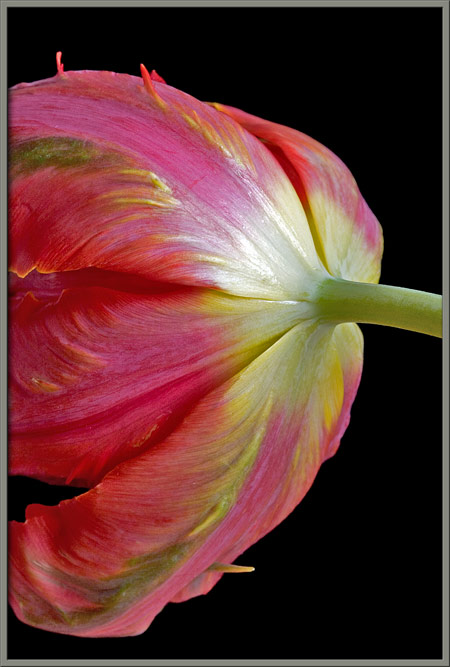

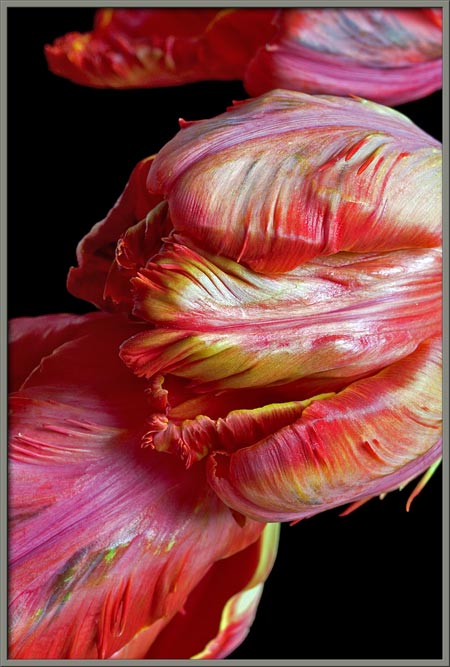

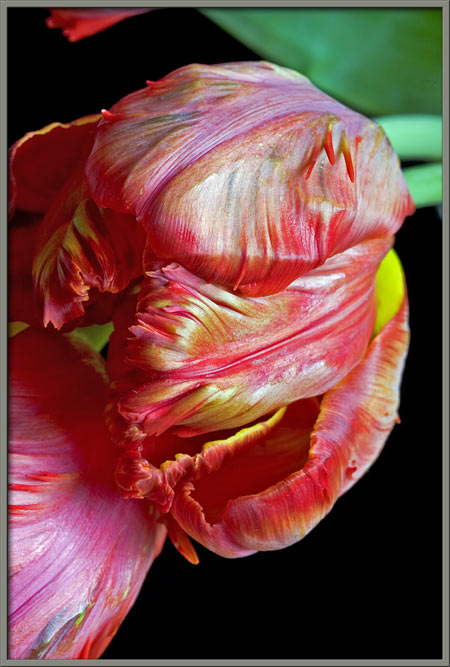

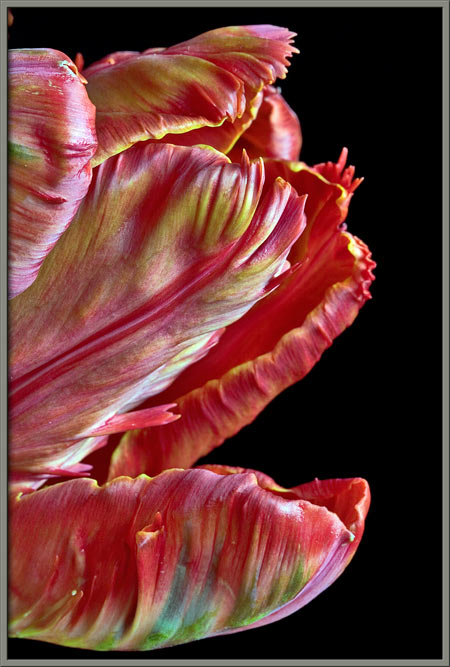

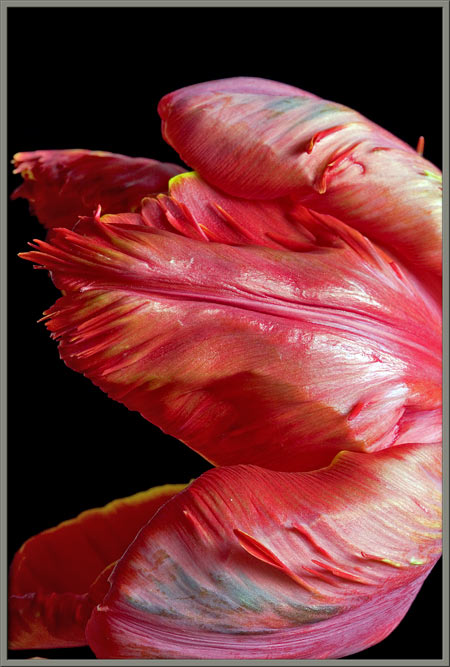

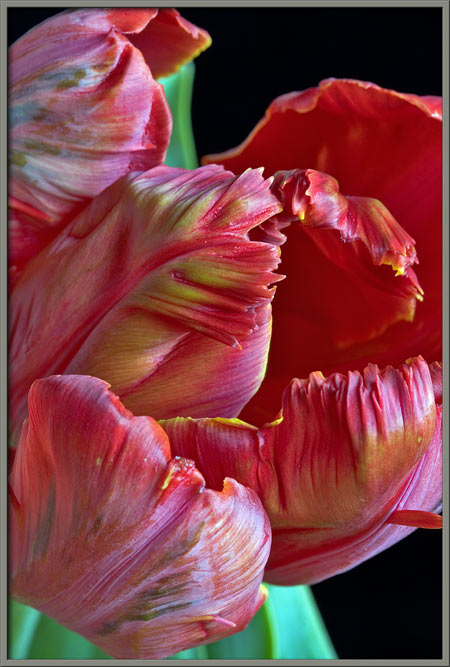

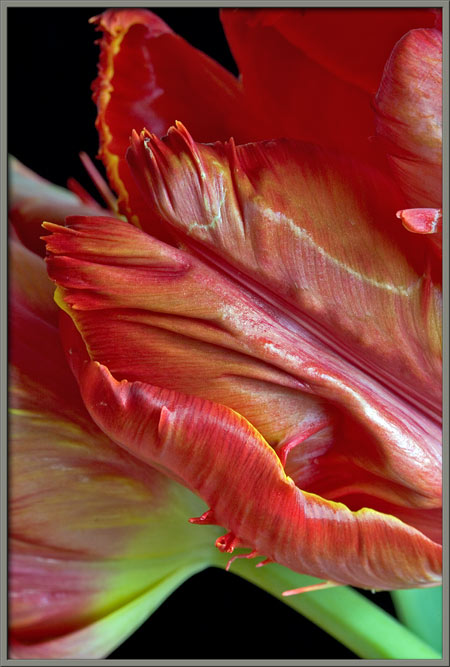

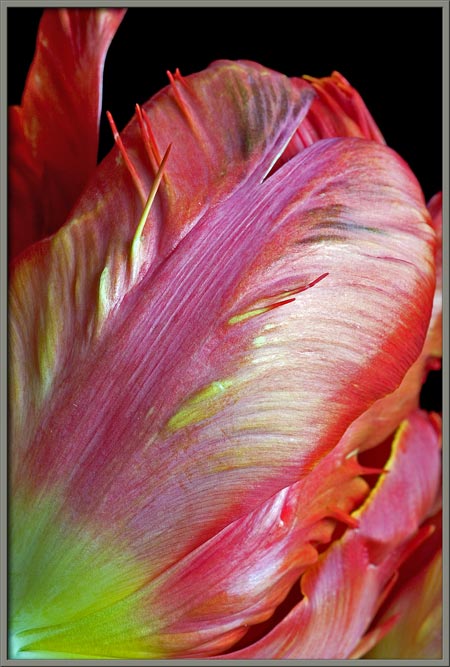

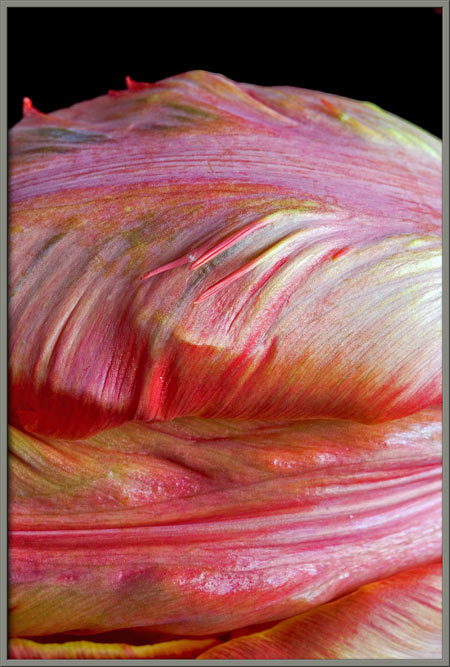

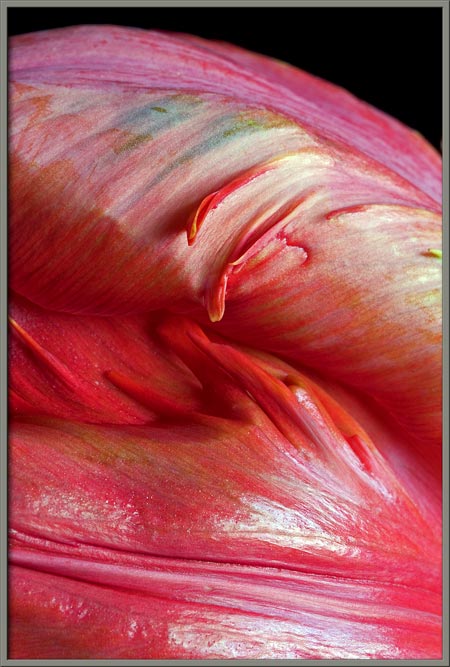

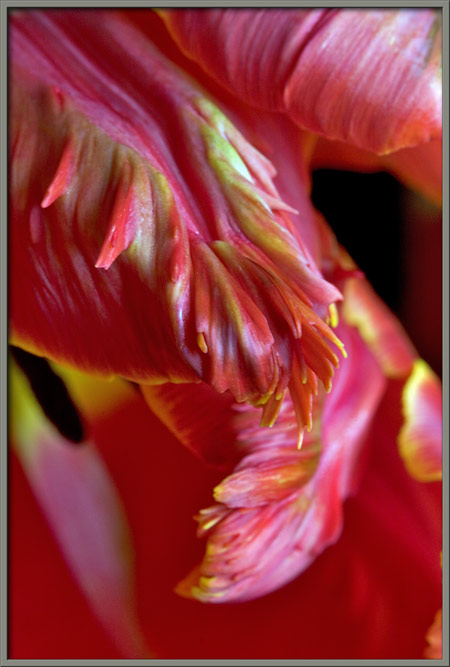

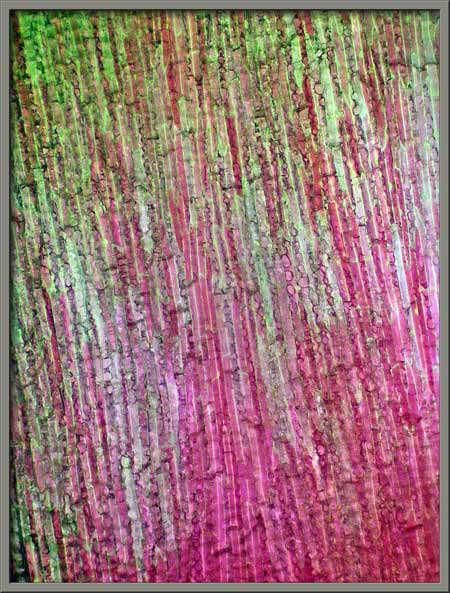

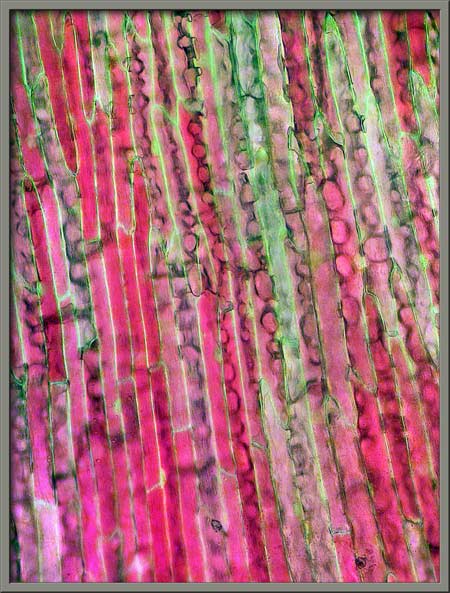

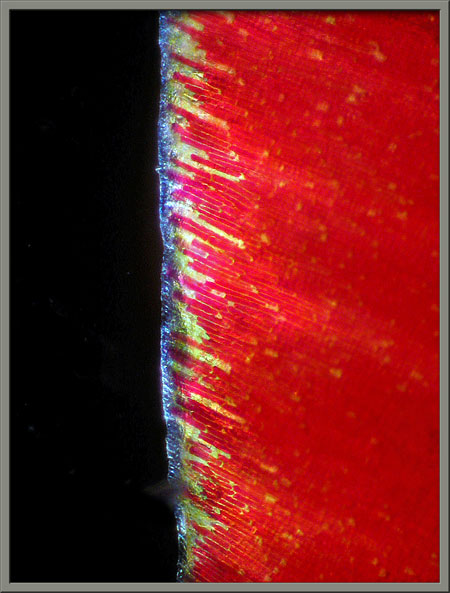

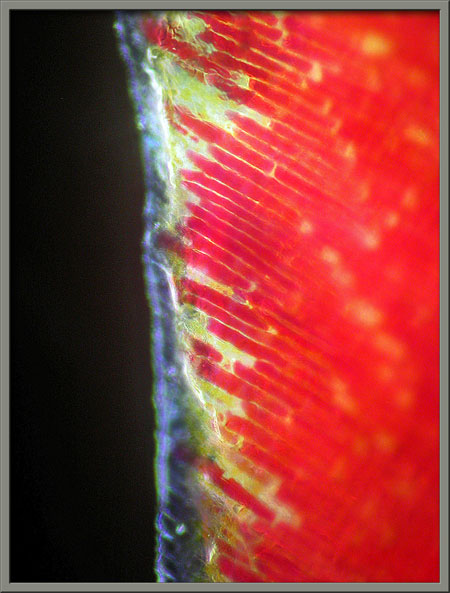

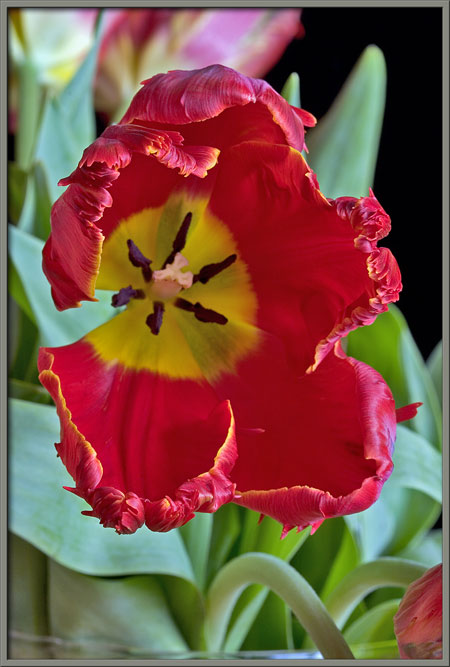

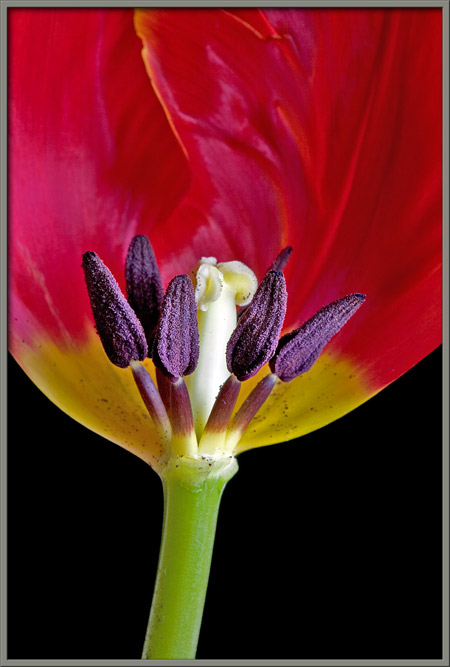

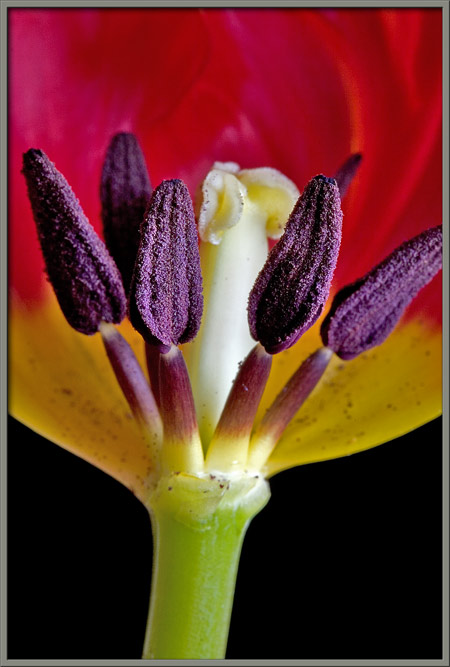

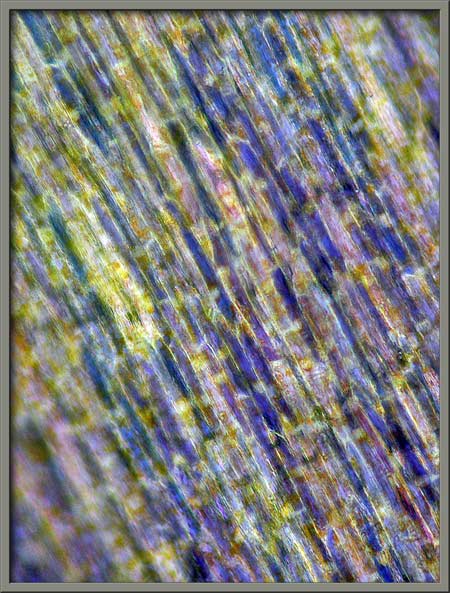

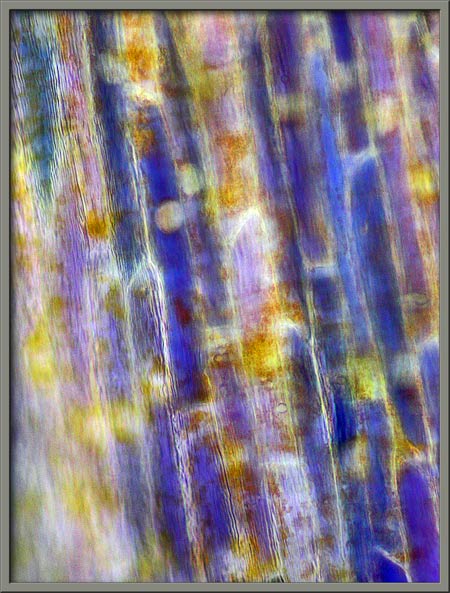

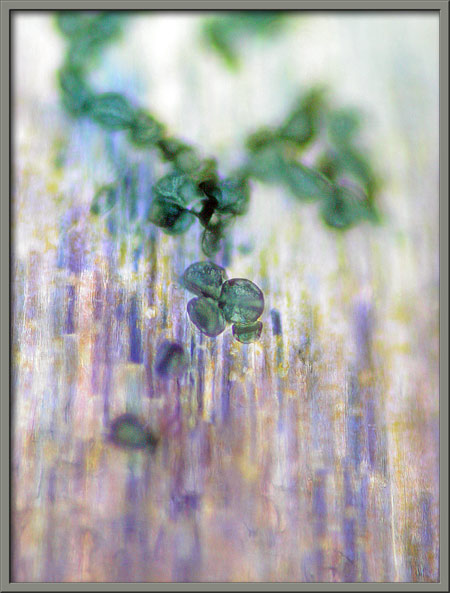

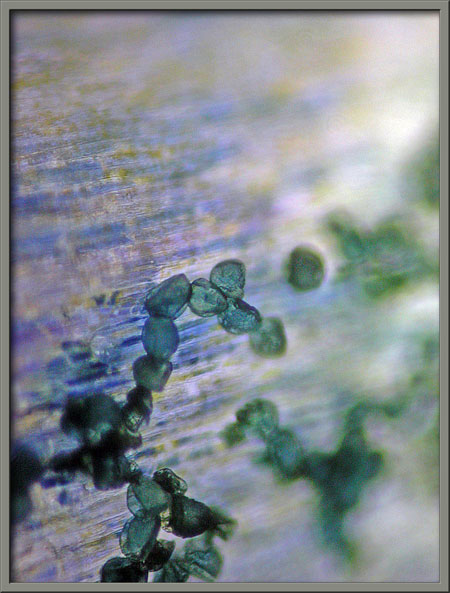

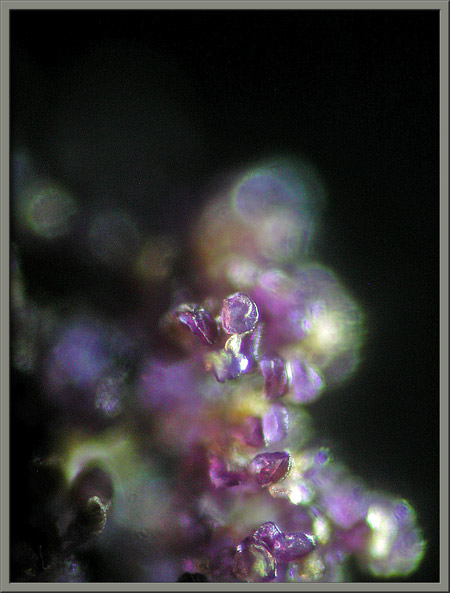

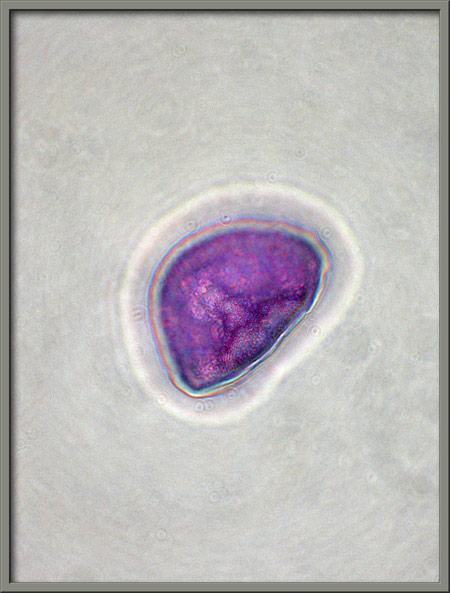

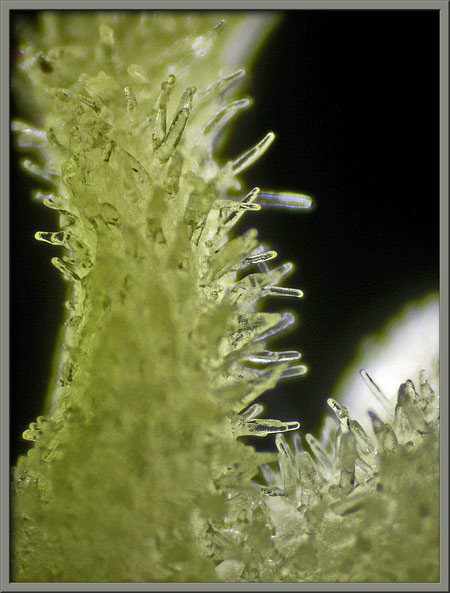

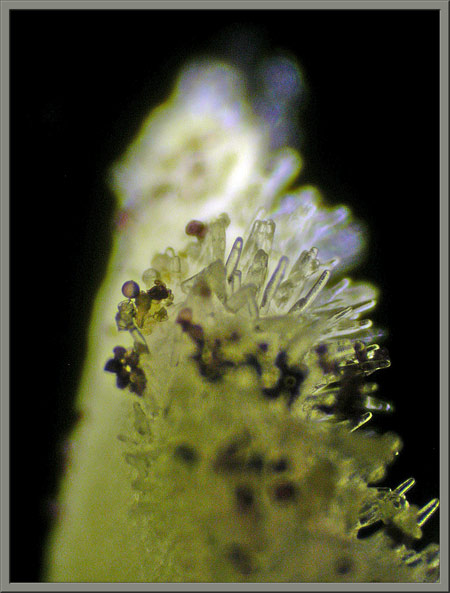

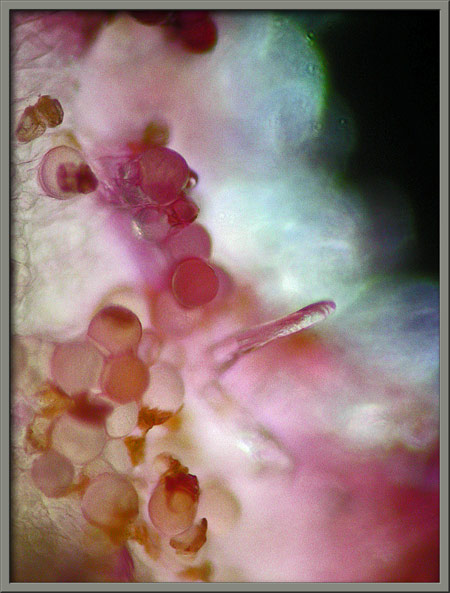

A Close-up View of Two "Parrot Tulips" Tulipa x hybrida Part 1

|

|

|

A Close-up View of Two "Parrot Tulips" Tulipa x hybrida Part 1

|

Published in the

December 2006 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .