|

A Close-up View of the Wildflower by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

|

A Close-up View of the Wildflower by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

As summer turns to fall, the roadsides of southern Ontario are coloured with the yellow blooms of Goldenrod and the purple flowers of New England Aster. The Aster family is the second largest on a global scale, with only the Orchids surpassing it in terms of number of species. Although some Asters are cultivated, most, like the one discussed in this article, are true wild flowers.

The photograph above shows the characteristic purple rays surrounding a yellow disk. Most blooms are two to three centimetres in diameter, with from fifty to one hundred rays. The one shown is a particularly fine example. Many blooms are less symmetrical, and have rays which are twisted and partially folded back. The image below of a portion of the main stem, shows this clearly. Most of the plants that I have observed are from one-half to one metre in height, with very strong stalks, and have a profusion of blooms at the tips of branches.

A closer view of several buds in the process of blooming reveals another characteristic of this plant; the pointed purple-green bracts (modified leaves) surrounding the rays.

Notice that the edge of the lance-shaped (lanceolate) leaves is also purple, and has very fine hairs around its perimeter.

The next image clearly shows the ring of bracts surrounding the bloom. Notice that they overlap in several layers - another characteristic of this family.

The flowers of New England Aster are wonderful, but in my view, it is the buds about to bloom that are particularly beautiful. Notice the contrast between the very rough surface of the bracts and the purple smoothness of the opening rays.

If you look closely at the image above, you will notice that the body of each bract is covered with what look like tiny hairs. Under the microscope, dark ground illumination reveals these to be glandular sticky protuberances. There are so many of these that the base of the flower may actually feel slippery to the touch. The image below shows the surface of one of the lower (greener) bracts.

The upper (purple) bracts have similar glandular protuberances.

At the very tip of each bract there are spiny protuberances in addition to the glandular ones. The image below shows these at the same magnification as the two earlier images. If you look carefully at the image of the bud about to bloom (third above), both types can be seen.

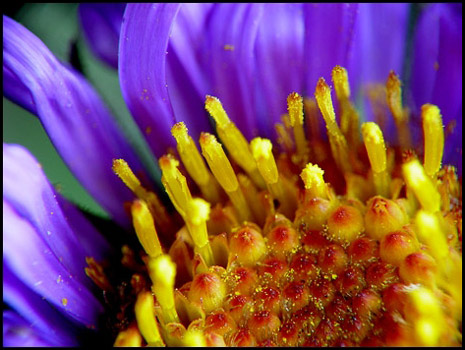

It may appear, when looking at the first photograph in the article, that the Aster is a single flower. In fact, it is a composite of many small flowers. Perhaps the most well known composite flowers are the Dandelion and Sunflower. Like the Sunflower, the Aster is composed of two types of flowers: disk flowers and ray flowers. The central circle of the bloom is made up of many disk flowers. In the image below, the red tipped disk flowers at the centre have yet to bloom. A little further from the centre, some have bloomed, and the tube-like corolla can be seen with the anther protruding. At the very edge of the central disk are the ray flowers. Each ray flower has a petal attached, so if you count the number of petals, this will be the number of ray flowers in the bloom.

If we move in closer, the individual disk flowers can be observed. Out of each tubular corolla a stamen protrudes. (The stamen is the pollen-bearing, or male organ of a flower.) Although hard to see, there are four or five stamens which are fused together by their anthers to form the protruding cylinder.

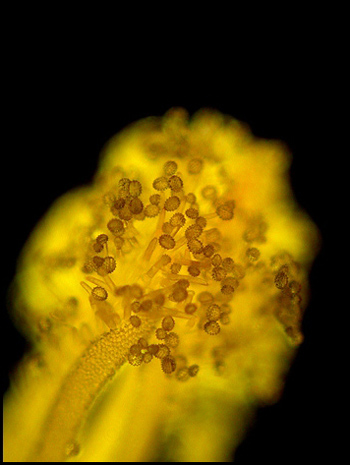

Under the microscope, (again using dark ground illumination), you can see one of the anthers in focus, covered with pollen.

At the edge of the central disk are many ray flowers. Protruding from each, in the image below, are two long stigma lobes. (The stigma is the female organ where the pollen lands.)

When observed under the microscope, a portion of one of these ray flowers reveals the purple "petal" (which should really be called the "ray"). To the right is the branching point of the two lobes of the stigma.

Using a higher magnification, the prickly yellow pollen grains of the New England Aster are visible sticking to a portion of a yellow-brown lobe.

Once pollination has finished, the rays of the bloom begin to turn brown and curl up like a party whistle.

Eventually the ovary transforms into a kind of fruit called an achene. (Non botanists call this the "seed".)

Photographic Equipment

The low magnification photographs in the article were taken using a Nikon Coolpix 4500 with natural light and the Nikon Cool light SL-1. Higher magnification images were taken using a Sony CyberShot DSC-F 717 equipped with an accessory achromat which screws into the 58 mm filter threads of the camera lens. (This produces a magnification of from 7X to 9X for a 4x6 inch image.) Still higher magnifications were obtained by using a macro coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4 Olympus SLR lens to the F 717. (The magnification here is about 13X for a 4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix 4500. The image below shows the Sony with the reversed SLR lens and the photographic setup.

For the macro photographs, aperture priority was used, with an f-stop of 8.0 to maximize the depth of field. Centre-weighted exposure determination was utilized in most images.

Conclusion

Although this exploration of a common wildflower will appear in a winter issue of Micscape, I hope that it will bring fond memories of the cool days of the early fall, and perhaps anticipation for the return of wildflowers next spring!

All comments to the author Brian Johnston are welcomed.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy

UK web

site at Microscopy-UK