Sponge City |

|

Sponge City |

|

I was diving on Tobago's Buccoo Reef when I came across an enormous loggerhead sponge. Remembering what I had learned, I flippered up to it and slammed my fist into the solid mass. (Lest anyone accuse me of destructive action and cruelty to sponges, please know that a sponge of this sort is a lot tougher than I am.)

Instantly the sea around me exploded in noise. Sharp reports reminiscent of firecrackers on a Chinese New Year made my head ring. The noise continued for a bit, then abated. Another slam and the furious response was even louder. "Aha, Alpheus," I muttered into my mouthpiece, "I hear you." Alpheus is not the name of the sponge, but its irritable pistol shrimp inhabitants who live within its cavernous chambers and channels—over 15,000 individuals in a sponge this size. Pistol shrimp make their characteristic noise with one claw's movable finger snapping down into a socket. Once I placed a solitary pistol shrimp in a porcelain basin of sea water, left it in the kitchen of a seaside cottage, and went to bed in a nearby room. Alpheus was unhappy in its confinement; so unhappy, in fact, that after a few sleepless hours and fearing the bowl might crack (it has actually happened), I took the complainer back to the bay in the dark of night.

Sponges are animals, a truth difficult for many people to accept. If one focuses on creatures with legs and eyes and complex internal workings, sponges undeniably are odd forms of life. Despite the variety of their overall form—they can be flat, stringlike, treelike, drum-shaped, rigid, glassy, soft, hard, dull or brilliantly colored—all are basically alike with two layers of only a few kinds of cells, and numerous interior cavities and canals. Where the coral of a coral reef no longer grows, the stony surface is thickly covered with marine algae, sea anemones, flowerlike hydroids, sea squirts, and sponges in a bewildering array of form and color. Drabness in the sponge world may be assumed, but it's rare. I've seen and photographed scarlet sponges, yellow, green, orange, rose and blue sponges, and the most beautiful of all, deep, rich, purple sponges.

When we landlubbers speak of a sponge (as long as it's not artificial and produced by DuPont) we envision a rounded brownish mass of flexible fibers. This is the skeleton of a particular group of sponges fished in all parts of the world for their many commercial uses after the living tissue has rotted and dissolved away. The fibrous material is fittingly called spongin and is superior in strength and lasting power to any imitation coming out of a chemical factory.

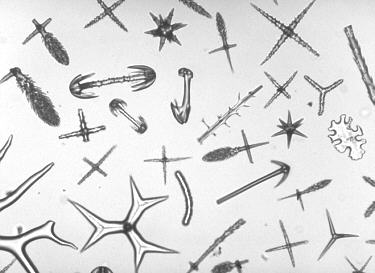

Other sponges have different kinds of skeletons made up of calcium carbonate or silica arranged in pretty little structural elements known as spicules. Some are needlelike, others are crescents, stars, knobs, hooked at one or both ends, and still others are the original Mercedes-Benz symbol—biologists call this design a triaxon spicule. A sponge biologist uses spicule shapes to identify his animals, not their overall appearance. When I look at the cluttered, tightly woven mass of spicules binding a sponge together, I am reminded of pickup sticks, a child's game where colored sticks lie in a tangled heap. You can hardly remove one stick without disturbing the rest. This sort of sponge skeleton looks like a hodgepodge when divested of living tissue, but when the sponge is alive, it hangs together very well and is enormously tough.

A variety of spicules from different species

of sponge.

Brightfield illumination

A sponge's life isn't very exciting by our standards. It sits on the bottom of the sea or in a lake (yes, there are freshwater sponges) and draws in water, extracts oxygen and microscopic food, then expels the water and with it carbon dioxide and other wastes. Our local lake and pond sponges are sometimes bright green, rather than their usual dun color, for this signifies the presence of symbiotic algae (Zoochlorella) that in exchange for having a good place to live and lots of necessary carbon dioxide, produce carbohydrates that the sponge uses as food. The bright colors of marine sponges have other poorly understood origins, mostly the result of their particular metabolism.

No matter what the sponge, even the simplest have internal canals and cavities through which currents of water continually pass. The flow is driven by tiny cells lining the internal spaces; they have whiplike flagella beating in a crude sort of synchrony. Each of these cells also has a meshed collar surrounding its flagellum, and the dynamics of propulsion and water movement result in microscopic food being drawn to the outside the collar. It is here that morsels are trapped on the mesh and ingested by the underlying cell.

How much water flows through a sponge? A single sponge about the size of your middle finger may pass 22 liters through its body in a single day, while a large sponge will pump over 1500 liters in twenty-four hours. The volume flowing through tens of thousands of sponges on a coral reef is prodigious—several millions of liters at the very least. Such transfer of water with its biological consequences has a profound influence upon a reef ecosystem.

All this is the sponge's business, but if various sizes of internal cavities are available, why not colonize them? So says Alpheus the pistol shrimp and a host of other small creatures—many kinds of shrimps and crabs, segmented worms, roundworms, flatworms, skinny little fish, one-celled animals—you name it, and it's there. What a fine place to live! Large predators are denied entrance, there is plentiful food coming by, lots of oxygen, waste products are promptly flushed away, and one's own kind is nearby for convenient procreation. Some inhabitants grow so large they can never again leave the sponge, but that doesn't seem to bother them overmuch. Their eggs and larvae easily escape to join the outside world of plankton and, if they survive, they'll eventually be drawn into another sponge during their travels.

I wonder if there are sponges anywhere in the world that do not support a community of residents? Not far from my house is a nice little pond that neighbors created thirty or so years ago. Because it is clear and sunlit, it supports many bright green sponges in branched array. Most visitors to the pond assume they are only stubby little plants, for they grow among algae and pondweeds that also depend upon photosynthesis. When I remove one of these sponges to study under magnification, I find all kinds of small creatures darting among the pores that take in and expel water. Once in a while I come across a minute green insect with lovely golden bristles. It is the larval stage of the spongefly and lives only on the surface of a freshwater sponge until it matures and flies away to another pond where it lays eggs, hoping (if insects hope) sponges are present.

My plea is only this: don't denigrate the lowly sponge. It works hard, night and day, cleansing water by sifting particles from the constant flow it creates with its tiny cells. Its lifestyle and oddly unexciting body structure create opportunities for a host of other lives who would sing its praises—if they could.

Comments to the author Bill Amos welcomed.

© 1999 William H. Amos

Bill Amos, a retired biologist and frequent contributor to Micscape, is an active microscopist and author. He lives in northern Vermont's forested hill country colloquially known as the Northeast Kingdom, and takes delight in studying the several ponds on his land.

Editor's note: Other articles by Bill Amos are in the Micscape library (link below). Use the Library search button with the author's surname as keyword to locate them.

Images by Dave Walker of a prepared slide of spicules from Oamaru, New Zealand. Slide prepared by Richard Suter a famous British slide mounter earlier this century.

Published in the August 1999 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor,

via the contact on current Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK