|

A Microscopical Alphabet of Images

Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

I was cogitating (a fancy word for daydreaming) about how to present a series of interesting random images which were not organized according to some unifying theme. I thought of the title “ A Potpourri of Images”, but that made me think of poop and coprolites and that wasn’t at all appealing. “A Miscellany of Images”? Well, that sounded pretty pedestrian. And then I thought, what about an alphabetical treatment; that wouldn’t require a unifying theme, it would be a bit of challenge, and it would allow me to ramble all over the place about some images which I find interesting. So, that’s what you’re going to get–an alphabet soup of images of things that you mostly wouldn’t like to find in your soup.

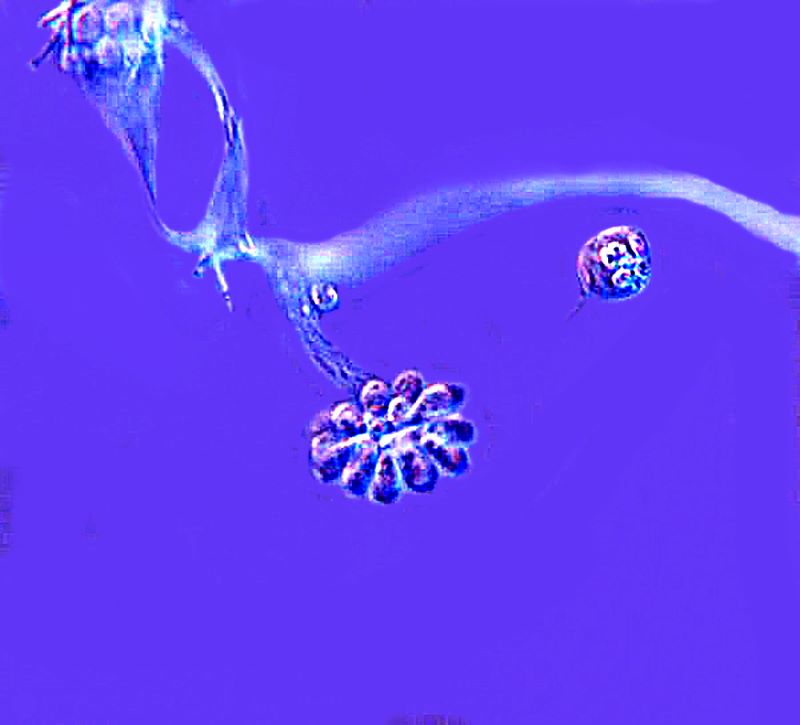

A is for Anthophysis vegetans–a colonial flagellate of extraordinary strangeness and a wonderful occasion to ramble–ramble, ramble, ramble. These remarkable little protists are a spheroidal cluster of flagellates with each individual having 2 flagella; the cluster is attached by a thin thread to a small brown branch which is attached to a little tree which is usually brown from absorbing iron in the water surrounding soil in the pond or lake. When you come across them in a dish of pond water and transfer some with a pipette to a slide, almost always one or more of the spherical colonies will be dislodged and go spinning off through the water to a destiny unknown. Do they attach and form new trees and colonies? I can’t find any record that anyone knows.–Listen up students; a good science project! There are many mysteries surrounding this wonderful little creature, but even if you’re not looking for a project, they are marvelous to observe and spend time with. I’ll show you 3 images. The first is a colony still attached to the branch; the second is the “invert” of the first, and the third shows a detached colony near a ciliate several times its size.

I am tempted to add an AA, and AB, etc. , but just allowing one entry for each letter is already going to make for a long adventure, so I will resist the temptation.

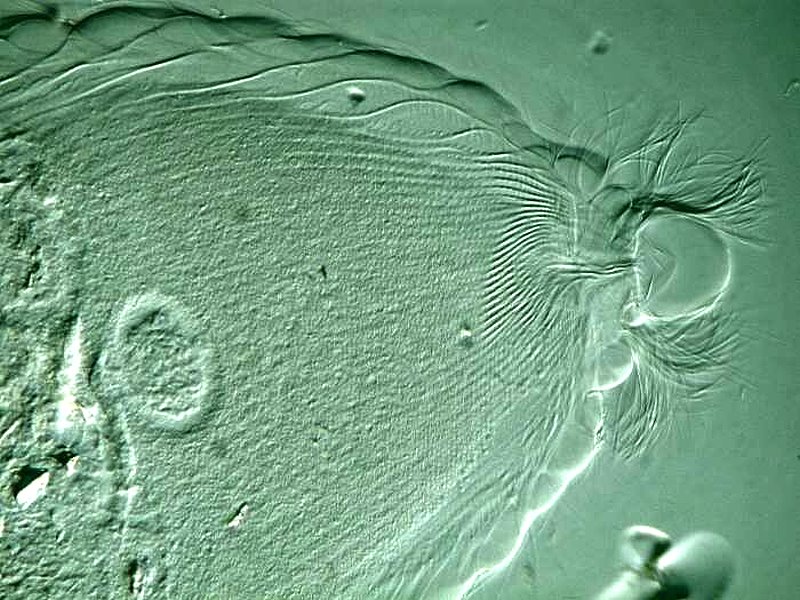

B is for Blepharisma. Here’s another opportunity for me to ramble on tediously, but I’ve already done that, so I’ll just provide some links to those previous articles and content myself here with showing you a couple of images with the briefest of comments.

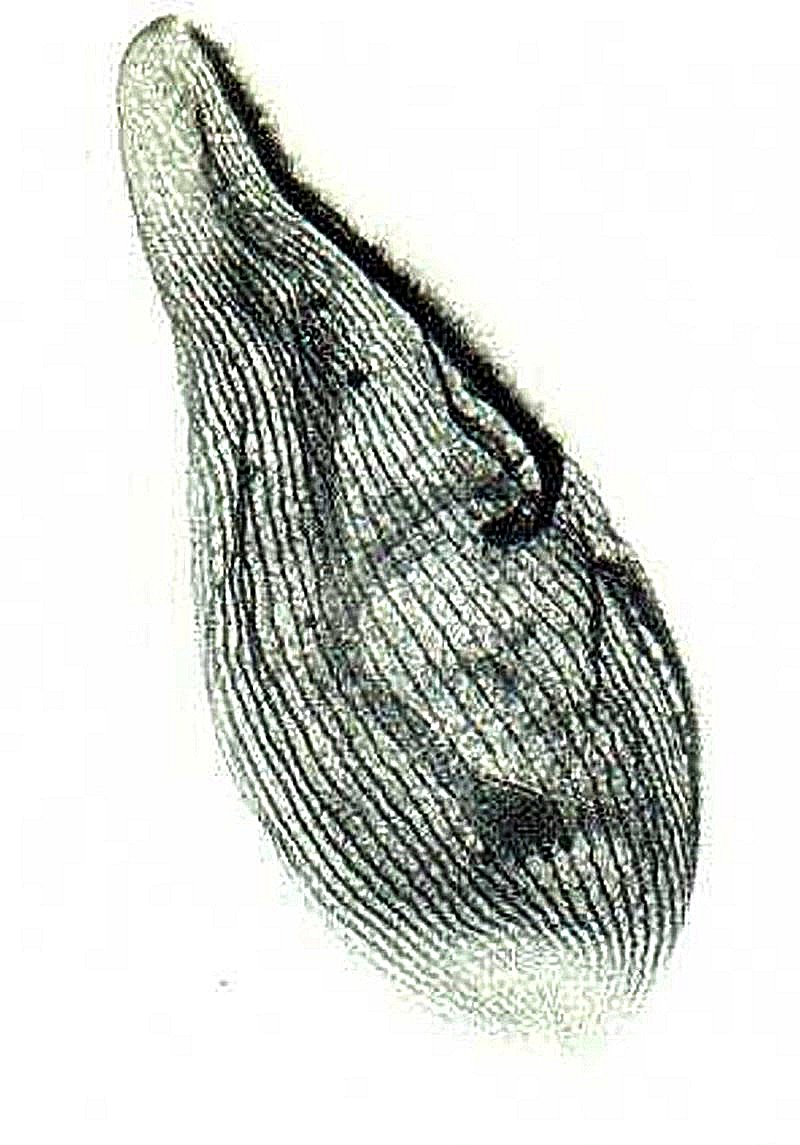

The first image is of a typical Blepharisma; notice that it has a distinct pinkish tinge which is typical of this species. It is a distinctive pigment called blepharismin and if exposed to too much light for a brief period turns out to be toxic to the organism, thus acting as mechanism to help it avoid areas of intense sunlight in the water column.

Blepharisma, for reasons not completely understood, will under certain conditions turn cannibalistic. Here is a so-called “cannibal giant” and the red clumps which you see inside are other Blepharisma that have been ingested and are now in the process of being digested.

Blepharisma, along with some other ciliates, possesses an elaborate system of fibrils known as the “silverline system”. They are visible only after the application of special staining techniques. This example used the Protagol silver staining method.

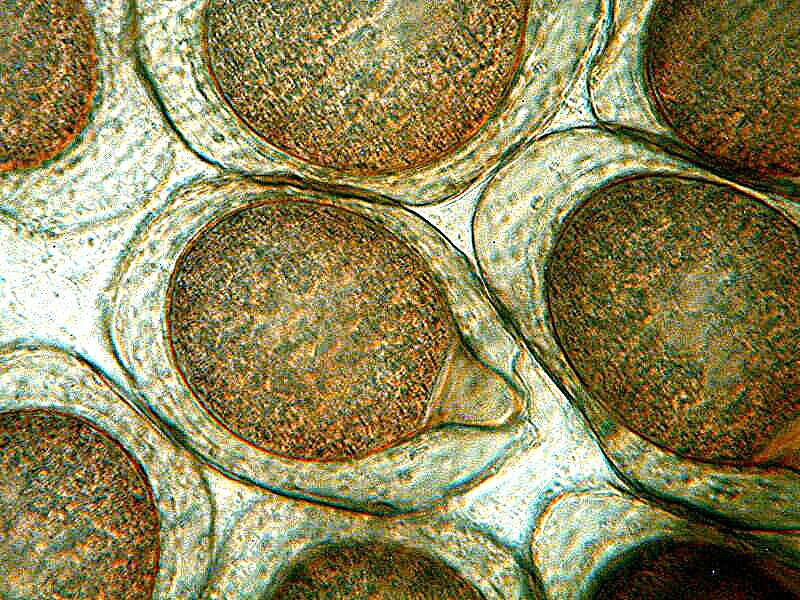

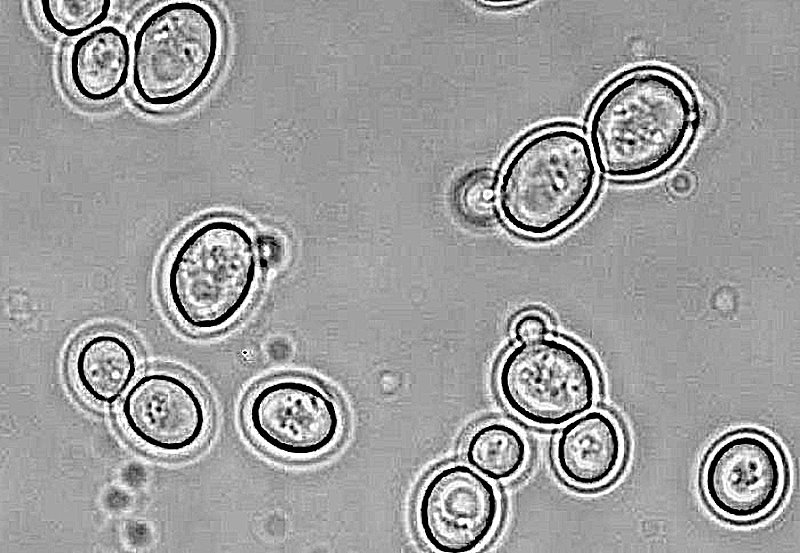

Finally, Blepharisma cysts are, in certain stages, highly distinctive as you can see in the images below showing what I refer to as the “nose cone” stage.

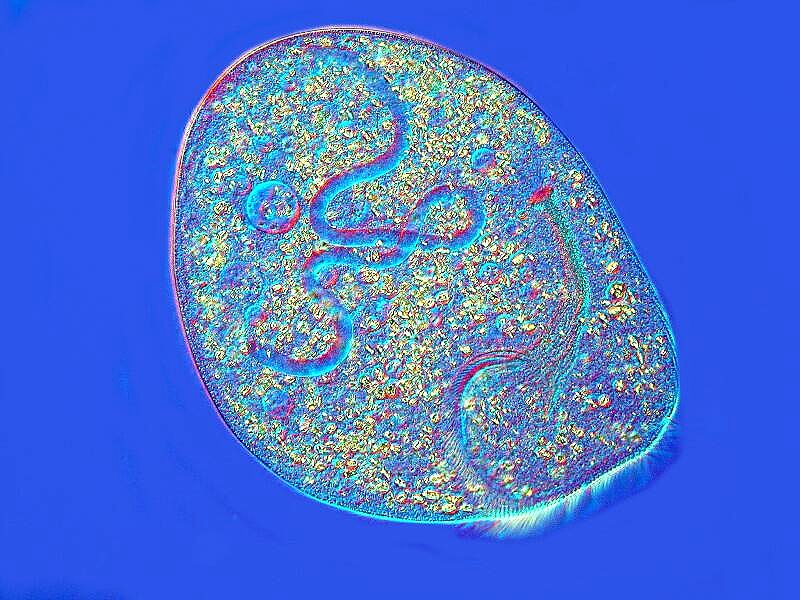

C is for Climacostomum, a large ciliate which I happened to find in a culture. They culture readily and are very interesting to examine. I was fortunate to find a specimen which was undergoing autogamy and I’ll show you a specimen of Climacostomum in its ordinary state and then when involved in autogamy which is the internal reorganization and repair of its genetic material. The images were taken using DIC and the second one was altered using graphics techniques to emphasize the nuclear material.

D is for Didinium nasutum, a medium-sized, incredibly voracious ciliate especially for Paramecia. It has a projecting proboscis which is lined with trichites and these can be moved to open and close the cytostome allowing it to engulf such sizeable prey as Paramecia. The 2 images were taken from a prepared slide with stained specimens. The first shows the organism alone and the second shows one engulfing a Paramecium.

E is for Euplotes patella which is a hypotrich with fused bundles of cilia called cirri. They can often be seen crawling around on the substrate or on vegetation; they look rather like little “bugs” with multiple legs.

The next image is Euplotes stained with silver, however, the initial image was not desirable since it produced an unpleasant orange color throughout. As a consequence, I altered it using the graphics program to increase contrast and show the cirri and a portion of the surface sculpting.

And in this one, I used a stain called Nigrosin to show the surface sculpting. Nigrosin is very good at showing such detail in those ciliates that don’t disintegrate on drying or get too distorted. I recommend trying it out on Paramecia.

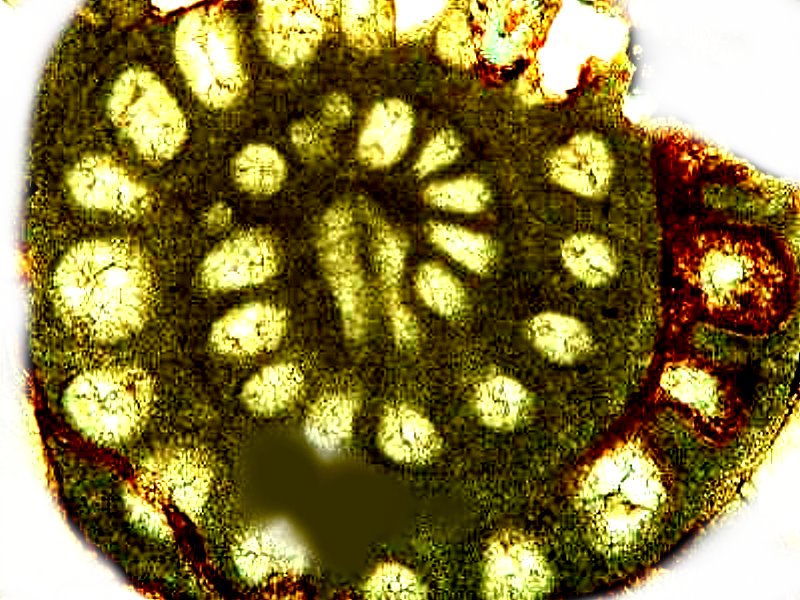

F is for Fusilinid. These are foraminifera, amoebae that formed stunningly complicated shells of Calcium chloride. They are extinct now and of special interest as an index fossil. They could get up to a size of over 2 inches. I will show you an image of the outer shell, then a cross section, and a diagram (from Google) demonstrating their complexity.

G is for Gromia. Here I am going to plagiarize myself from another article which I wrote recently and I don’t want to have to reconstruct it. A fascinating, very strange critter related to the foraminifera is Gromia, and there are at least a couple of freshwater species, although the vast majority are marine. For a bit over 2 years, I maintained a small marine aquarium and I found a few specimens and my friend, Mike Shapell and I, studied them in amazement. We looked at them using a Wild Heerbrugg inverted microscope and observed that these specimens of Gromia could extend their pseudopodia out to 8 or 10 times the length of their shell. At higher magnifications using phase contrast, we noticed that protoplasm was flowing in both directions along the pseudopodia in the manner of a 2-lane highway. We watched in astonishment as small diatoms would be transported back toward the “oral” aperture while protoplasm on the other side was flowing in the opposite direction. So, keeping a small marine aquarium to grow algae and protists without worrying about fish food and predators is enormously rewarding and relatively easy. It can be a source of many, many wonders for the microscopist.

H is for Howeyolozoon (A very large group of organisms not named after me). Actually, the entry for this letter is Halteria grandinella, a hypotrich with ductile, highly elastic cirri (bundles of fused cilia) which gives it the extraordinary ability to suddenly bounce out of your field of view, just when you have it in focus. As a consequence, I have managed to get just a single image of this little impish creature and you can see it below. If you look closely, you can see the macronucleus right at the center of the organism.

I is for Ichthyophthrisius multifiliis. You look it up. I couldn’t resist the name which is also known as “Ick” and as a hint, I’ll tell you that it’s an ectoparastic protozoan of a quite nasty sort. I don’t have any images of it but, I’m sure you can find some on the Internet.

J is for Jorunna, a lovely little nudibranch which looks like a tiny black and white bunny. I’ll show you an image from the Internet and suggest that you go to Google and type in “nudibranch” and then click on images and you will find a feast for your eyes in terms of color and diversity of these extraordinary little creatures.

K is for Kellicottia longispina a fascinating and elegant rotifer with long spines one or two of which may be longer than the body and 4 to 6 shorter spines, depending upon the species. This is such a remarkable creature that I will show you 4 images of it. The first 2 are of individual specimens.

This third image shows 2 specimens who may be just dancing or they may be mating.

Here again, we have 2 specimens and the one on the left has what is apparently an egg sac.

L is for Lycanthrope. (Sorry, but the full moon does strange things to me–Let’s try again.

L is for Litonotus, Loxophyllum, Lissothuria and a whole bunch of other stuff which I don’t have images of. So, let’s try once more.

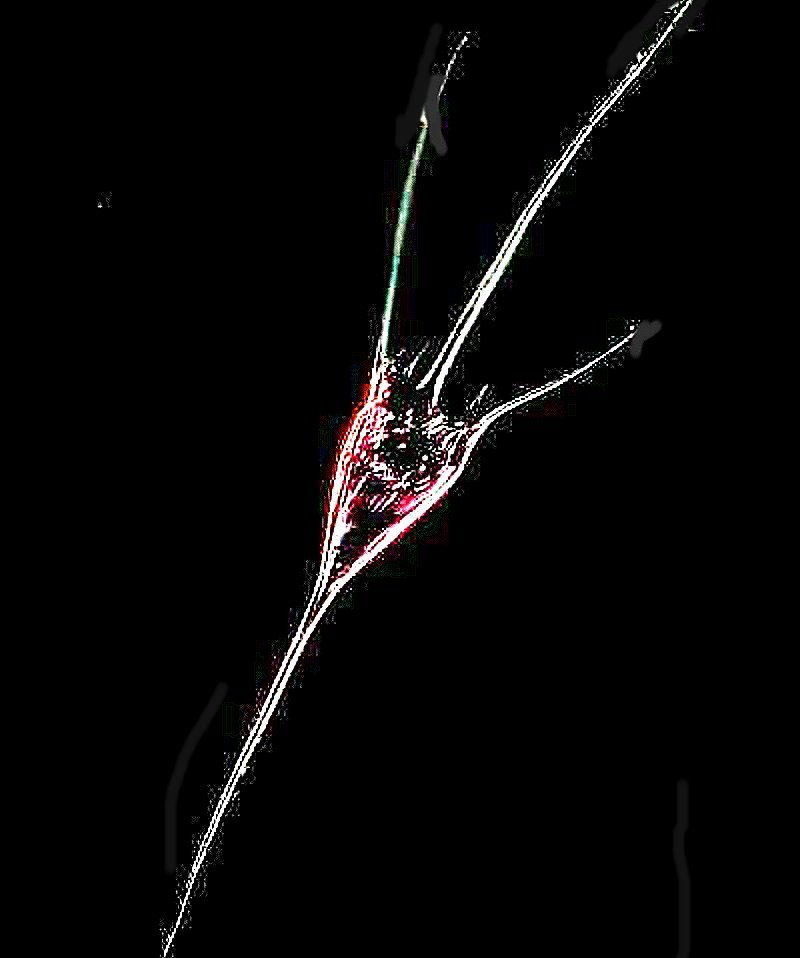

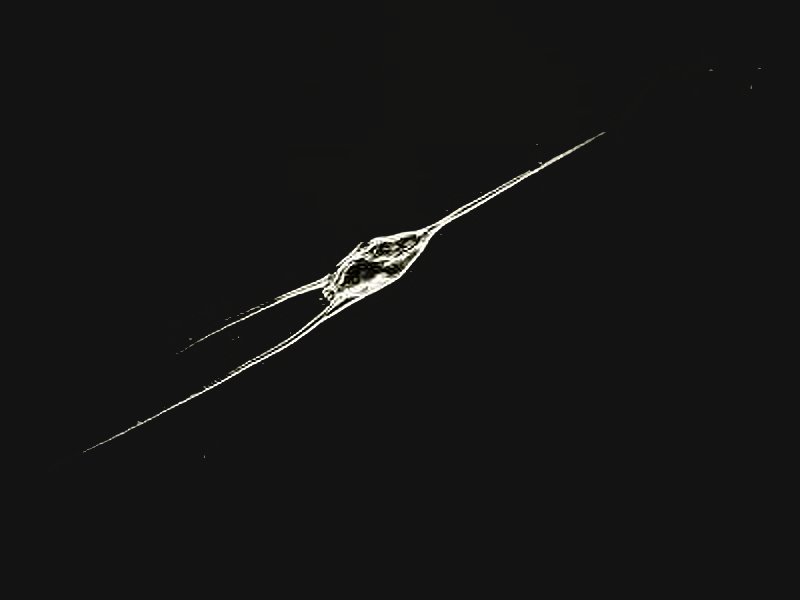

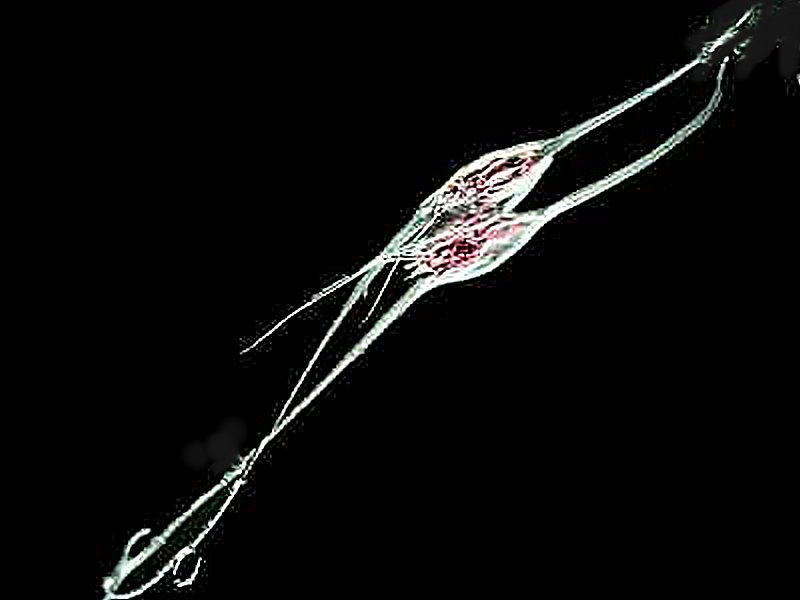

L is for Lacrymaria. Unfortunately, I only have one image of a contracted specimen. When I was doing the research on this incredible organism to eventually publish a little paper on culturing it, I didn’t have the kind of equipment which I have now. However, the extensility of the “neck” in this organism is so extraordinary that it challenges the norms of the limits of the ability of fibrils to extend and bend. It must be seen to be believed; fortunately, there are a number of microscopists who have been able to capture this marvel on video and I’ll give you links to a couple here. In the second one, there are some other organisms shown near the beginning, but keep on going, because there are some more remarkable views of Lacrymaria at link 1 and link 2.

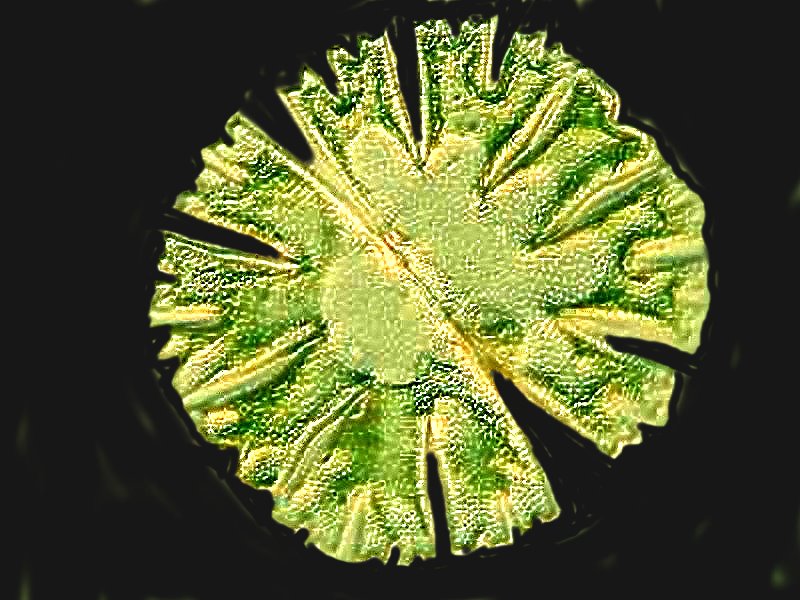

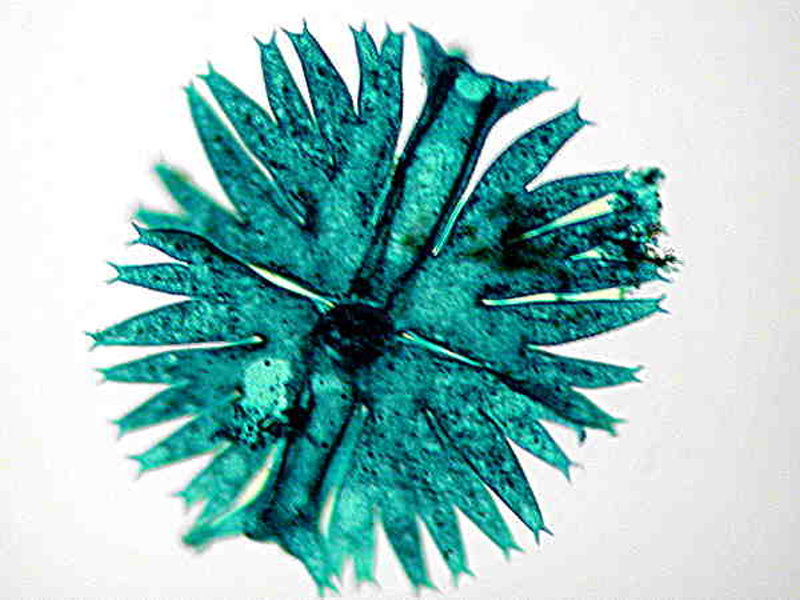

M is for Micrasterias, which is a beautiful desmid. Desmids are superb organisms that should rank high on every microscopist’s list. They are often elegant, deceptively simple looking, but they are remarkably complex and their forms are aesthetically pleasing. The wonderfully creative Polish microscopist Marek Miś has produced some of the most impressive images of desmids (among other things) that make my 2 images look quite plain. I will first show you an image taken with DIC and then one from a stained prepared slide. Also visit the site of Marek Miś.

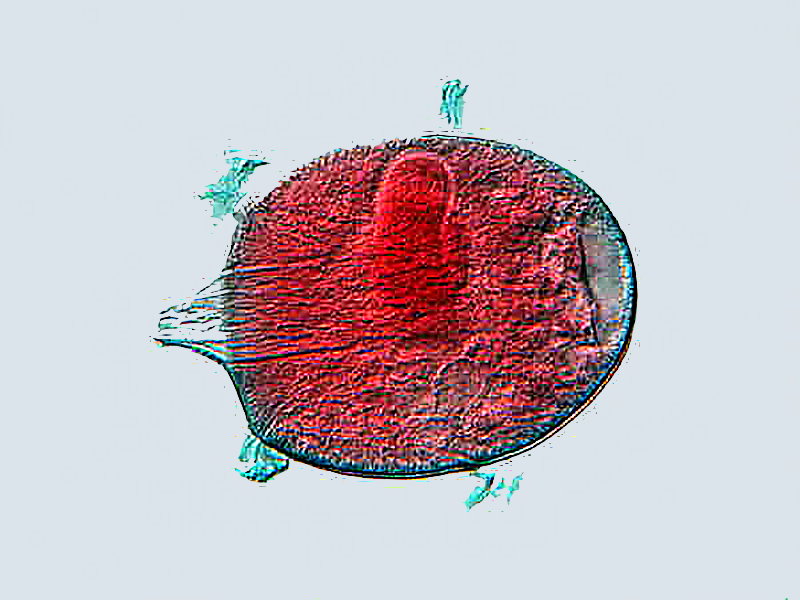

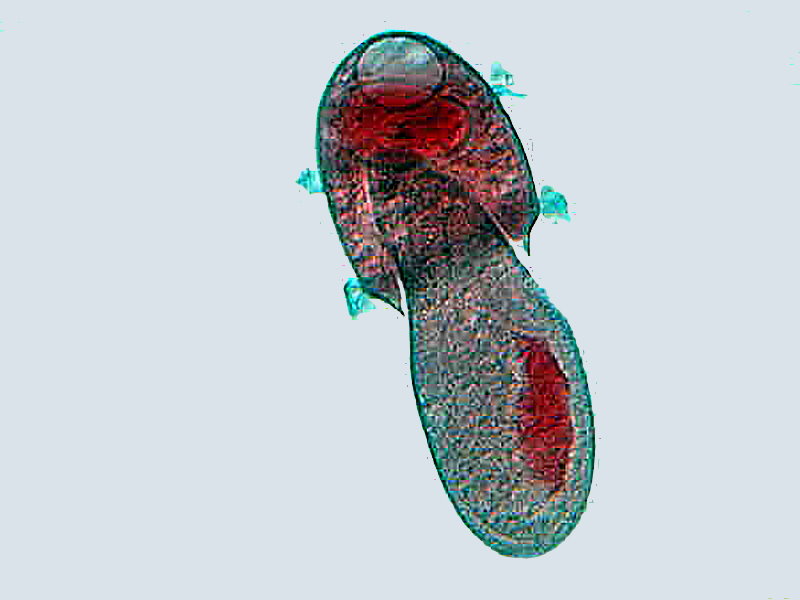

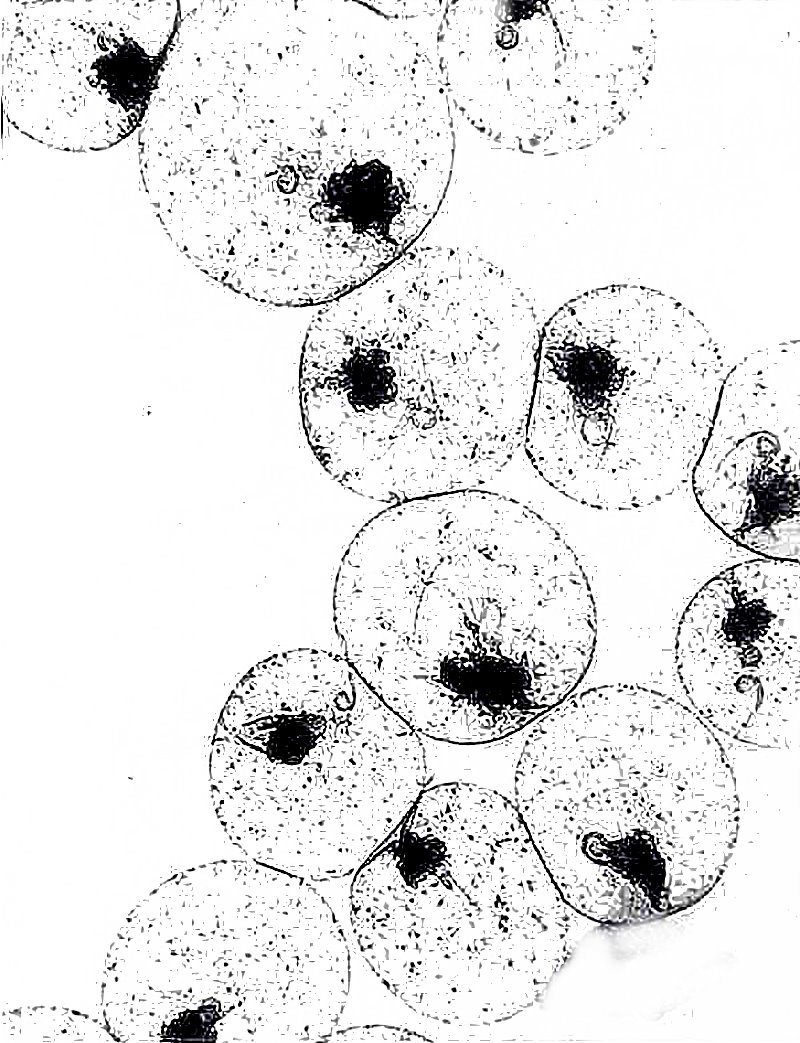

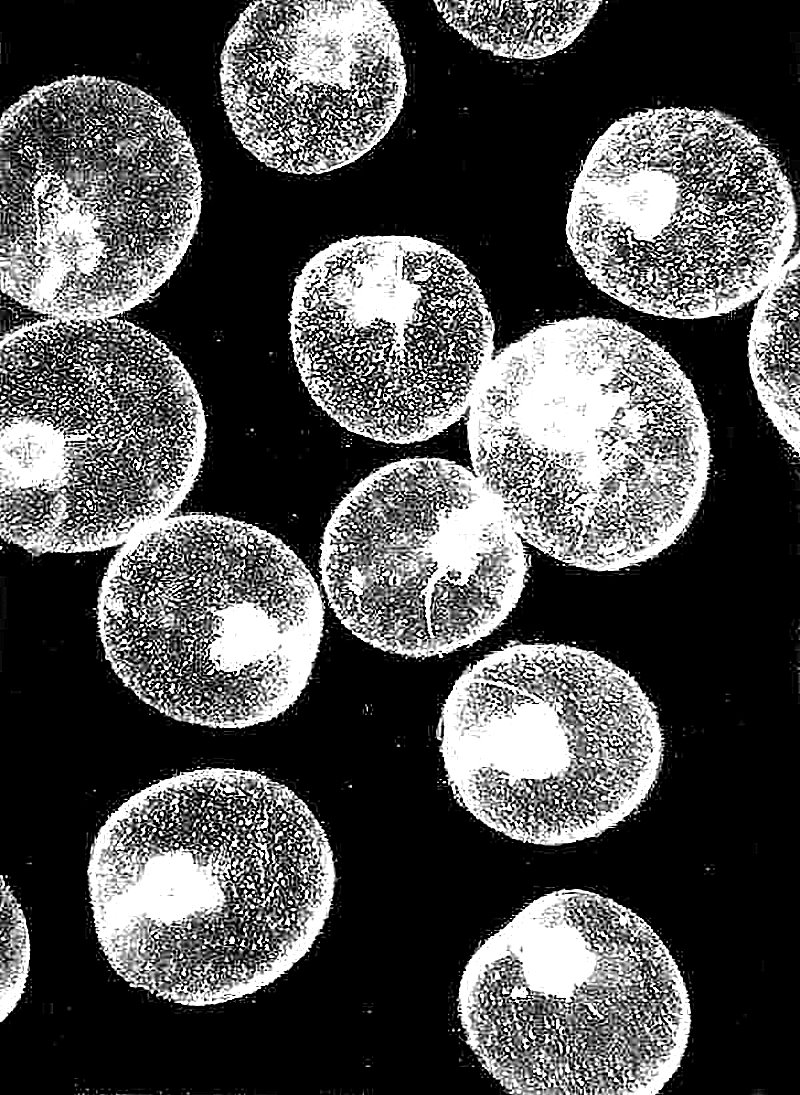

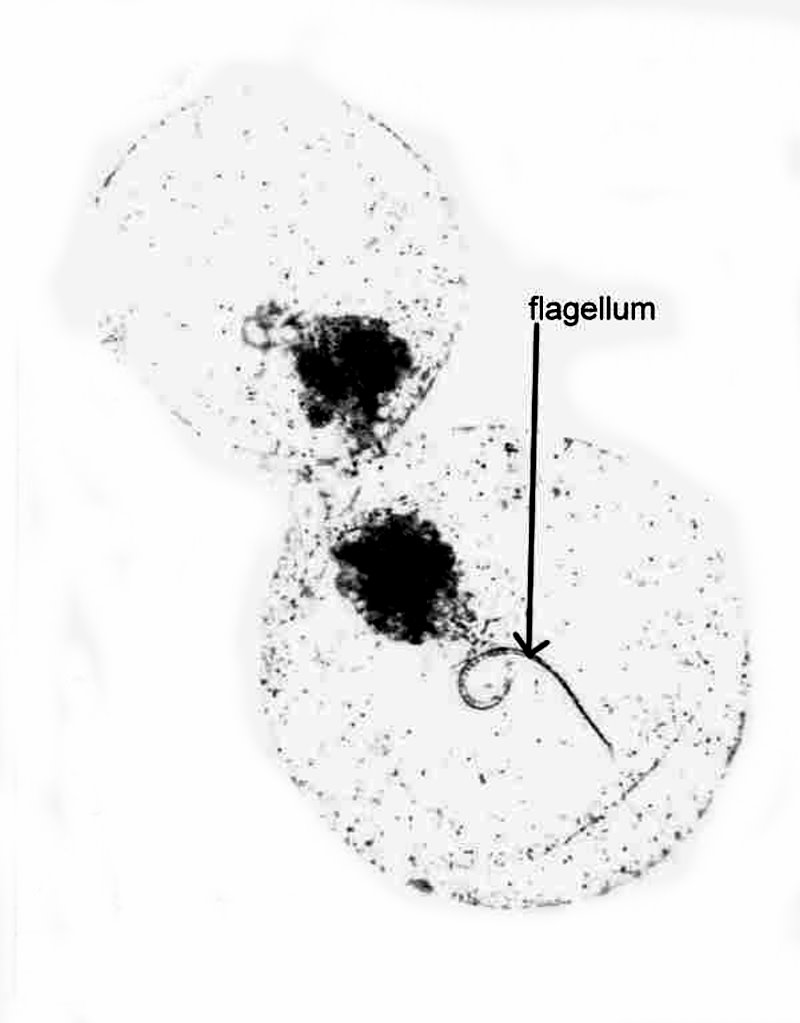

N is for Noctiluca scintillans. Most people who have been at sea at night for any length of time are familiar with the affects of this organism; when disturbed by a night diver or a boat, the blue light in the wake is due to Noctiluca which is thought to be a dinoflagellate, although taxonomists are still quibbling about that. This phosphorescence is often referred to as “sea sparkle”. There is a form that has a red pigmentation in its vacuoles and when the temperature conditions and nutrients are right, it can reproduce in such staggering numbers that it produces “red tide” which can be toxic to aquatic creatures and humans. The 3 images which I have were taken with a Polaroid microscope camera years ago, long before digital microscope cameras became affordable. As a consequence, the images are primitive, but show the basics. The organism is a flat disk with a “tail” which is its flagellum. First, I’ll show you a cluster of Noctiluca, then a darkfield image, and finally a closeup with a view of a flagellum.

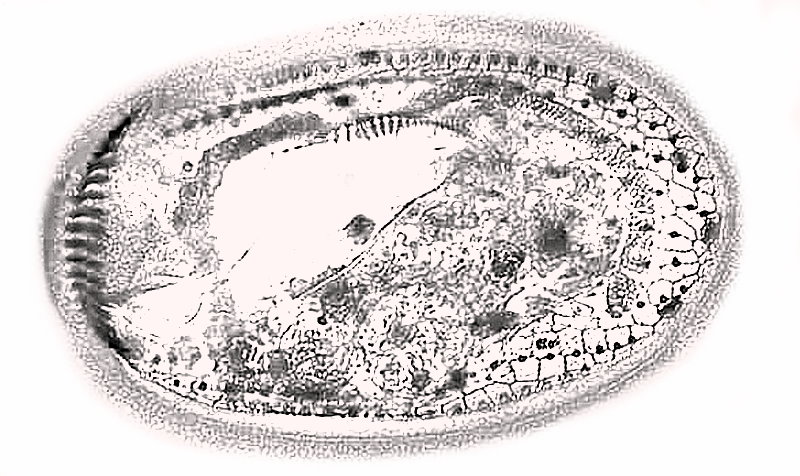

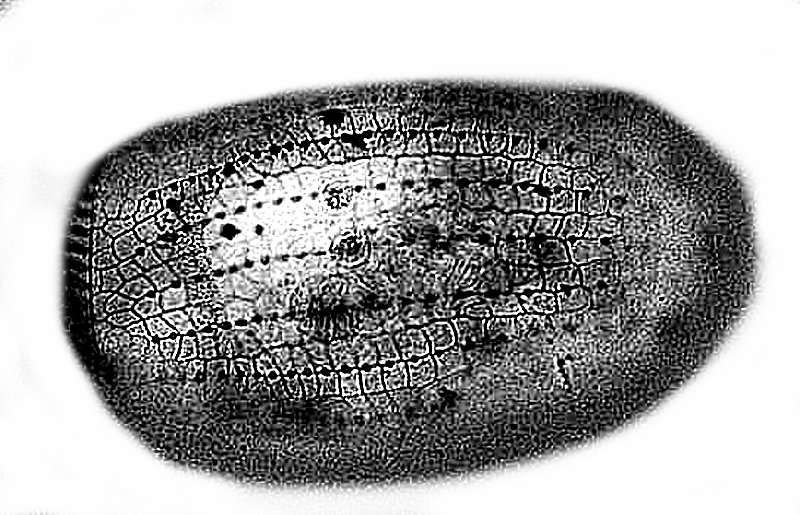

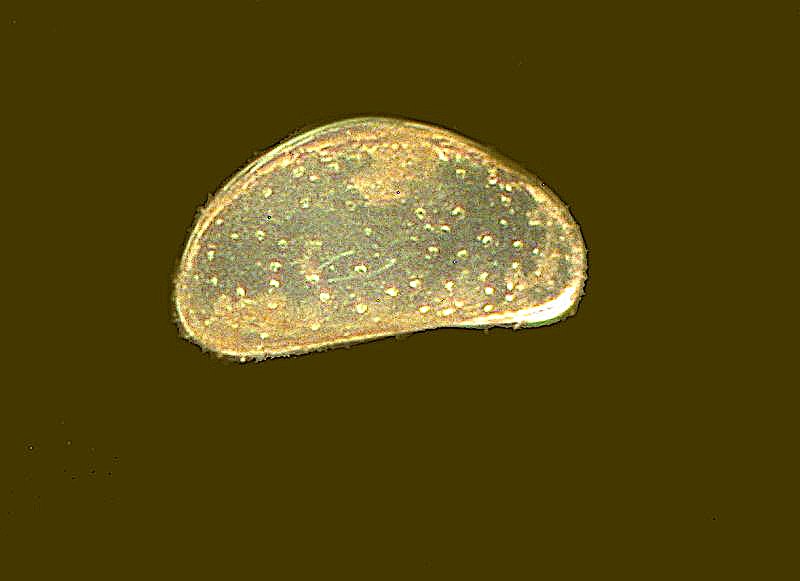

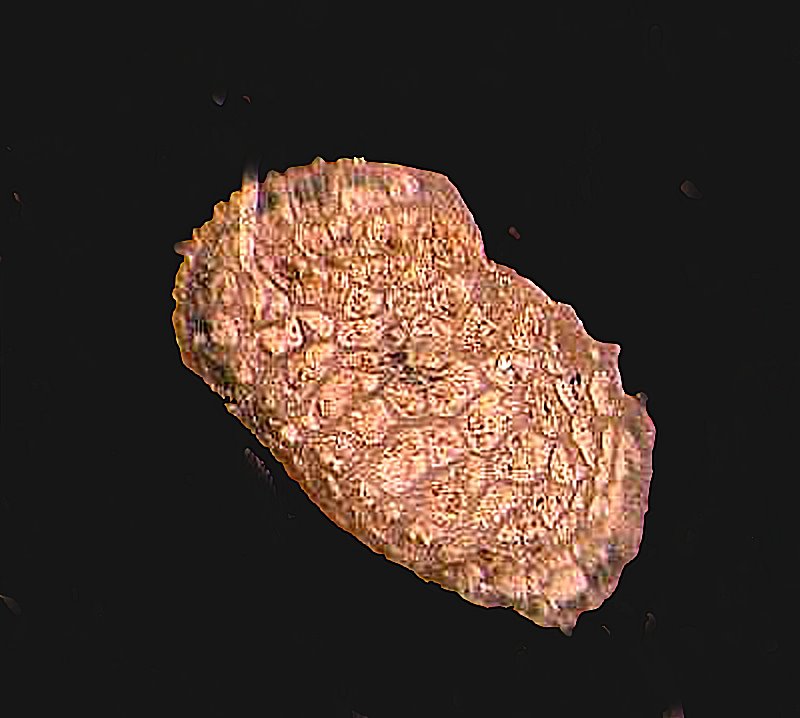

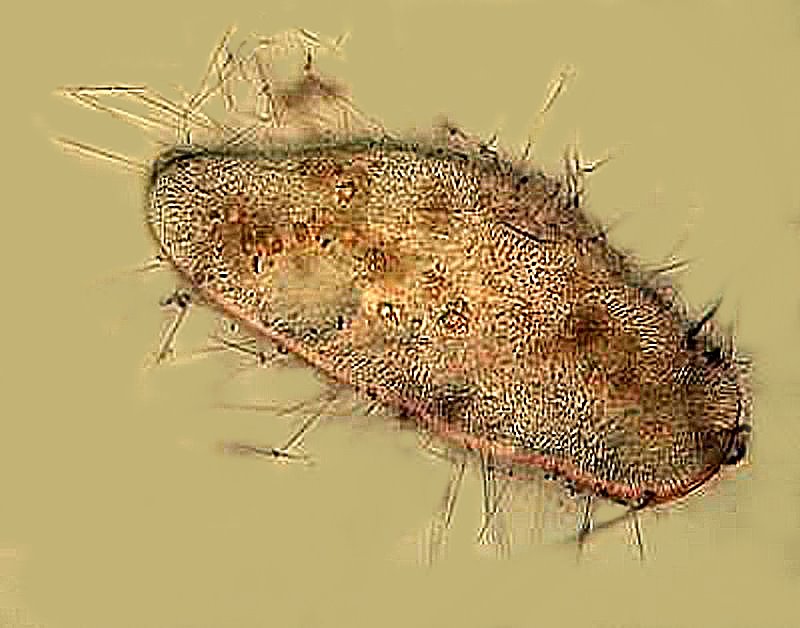

O is for Ostracoda. These are very small crustaceans which look like little seeds. They have a long fossil record–over 500 million years. The living ones can be found in marine, brackish, and freshwater environments. They boast the oldest known fossilized penis dating back 425 million years and living ostracods are sometime described as the “Don Juans” in the world of small creatures. They have 2 penises, actually 2 hemipenises and produce extraordinarily long sperms cells which in an Australian species measure up to over 11 and a half millimeters in length which is slightly over 3 and a half times their body length. First, I’ll show you the shell of what is likely a female; they are generally somewhat smaller and more rounded, whereas the male shells, as can be seen in the second image, tend to be more elongated to accommodate the large reproductive apparatus. Note that there is a kind of iridescence to this shell. The third image is of a fossil ostracod and is highly textured.

P is for Paramecium. Ho boy! Here comes a full-blown 90 page essay. No, no–just kidding. I’ll limit myself severely and just point out the paramecia are crucial in the history of protozoology. It’s highly likely that Leeuwenhoek observed them and Huygens described them in 1678. There is significant disagreement regarding the number of species which is, in part, due to the designation of subspecies and mating types. However, since, I have already written about paramecia on Micscape, I’ll let you look that up if you want more. Here I’ll content myself with showing you 4 images that show a few of the more interesting aspects of this extraordinary animalcule.

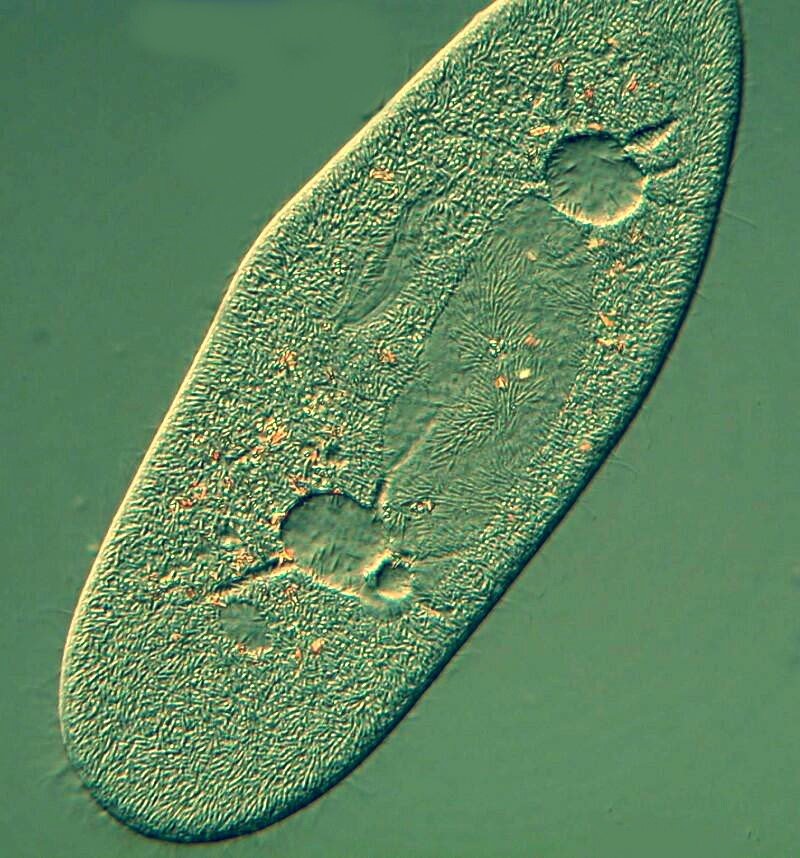

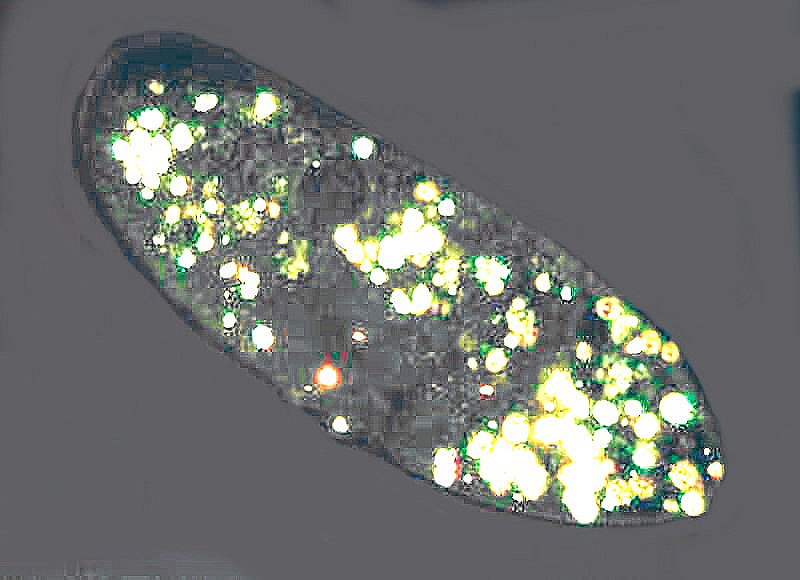

The 2 images give a general picture of the organism and were taken using DIC. In the first image, we see the typical oblong shape and a large number of vacuoles.

The second image reveals even more detail. We can observe 2 sizeable vacuoles with “canals” leading into them. These are the “contractile vacuoles” which help to regulate osmotic pressure. When Paramecia feed, extra fluid is taken in and accumulates; these structures collect the excess and periodically contract expelling the fluid they contain back into the surrounding environment. Running the distance below the 2 contractile vacuoles is a large ovoid mass which is the macronucleus.

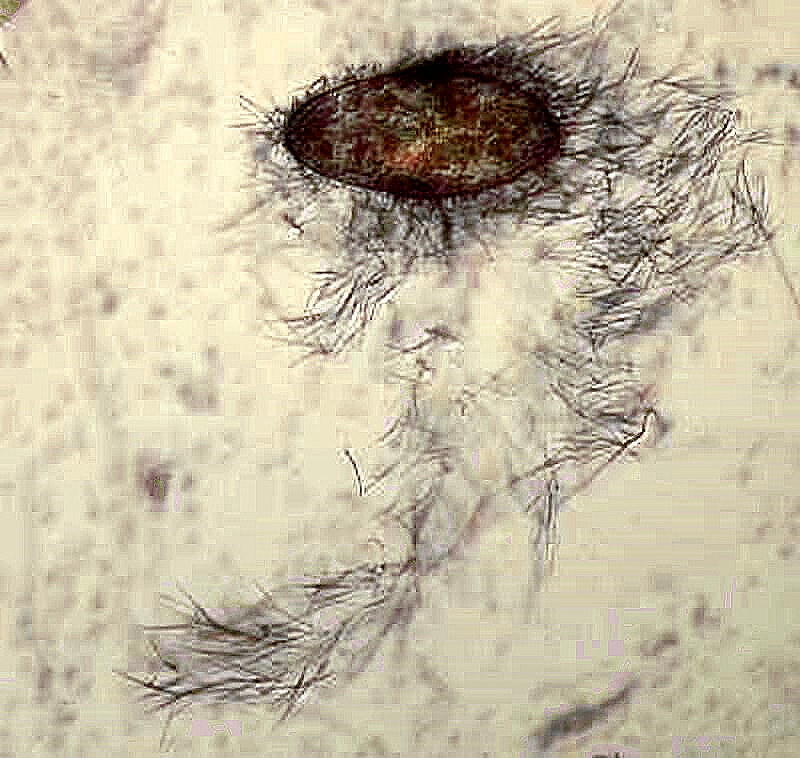

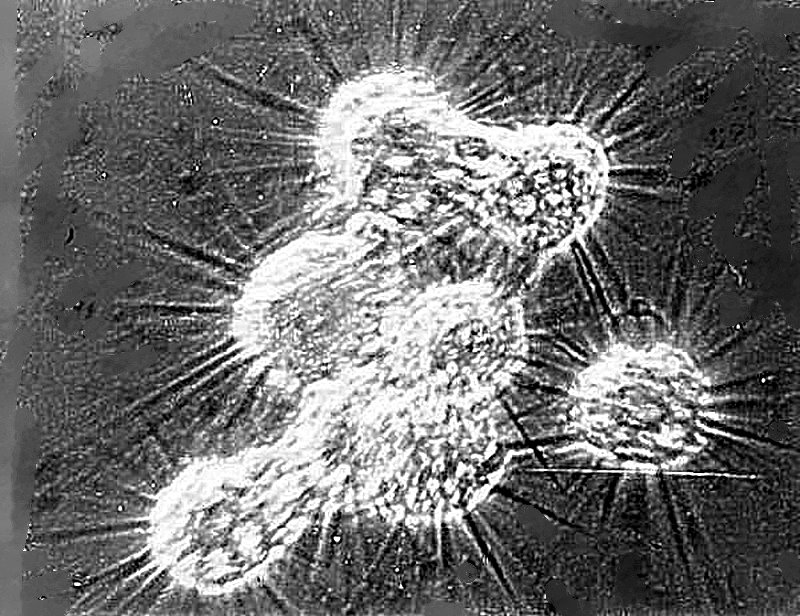

If you look very carefully at the area, especially on the left side, just inside the outer boundary or the pellicle or envelope, you can see hundreds of tiny yellow lines extending the length of the organism. As a matter of fact, if we remind ourselves that this is a 3-dimensional organism, these little “tubes” can be found all over the entire surface of the Paramecium. These “tubes” contain trichocysts which are minute threads with a pointed tip. Some researchers think that their primary function is defensive, although when a massive expulsion takes place, it might result in some damage to the Paramecium itself. I induced extrusion by using a toxic stain and the results are amazing in terms of the number of trichocysts and the distance which they can be “shot out”. This can be seen in the third and fourth images.

And finally on the Paramecium front, an image taken using polarized light. A number of ciliates and, quite prominently, Paramecia, have many crystal inclusions. These can consist of a variety of substances, among them, Calcium oxalate, Calcium carbonate, Silica, and Uric acid. A number of these are birefringent and so show up quite distinctly with polarized light as you can see below.

Q is for Quadrulella. Ha, you didn’t think I could up with a “Q”. I did think of using Quetzal and its feathers for a minute, but then I realized that it’s endangered, so I rejected that option. Quadrulella is a testate amoeba which constructs a shell which has the appearance of a series of rectangular plates. I don’t have any images, but here’s a nice one from the Internet (Microworld—Ferry Siemensma) .

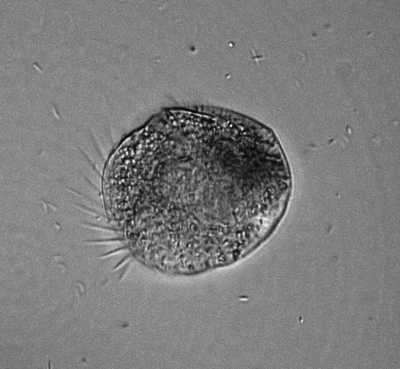

R is for Raphidophyrs. This is a bizarre amoeba which I found in a highly alkaline lake at an altitude of 7,200 feet. It has a spiny appearance from the pseudopodia which it extends from its sphere shaped body. Groups of these amoebae cluster and form sticky nets that are virtually certain to capture any small prey that happen to venture into their territory. Remarkably, after feeding, they separate and go back to their individual existence. Once again, my image is a very old one from back in those days when I only had a Polaroid microscope camera.

S is for Stentor. This protozoan is one of my wife’s favorites to take a look at when I’m examining pond samples. It is trumpet-shaped when extended, is highly contractile and, so far, about 25 species have been identified. The largest and most impressive is Stentor coeruleus which has a distinctive pigment known as stentorin giving it a blue-ish green color. First, I’ll show you another fairly common species largely extended except for the cytostome and then an image of it contracted.

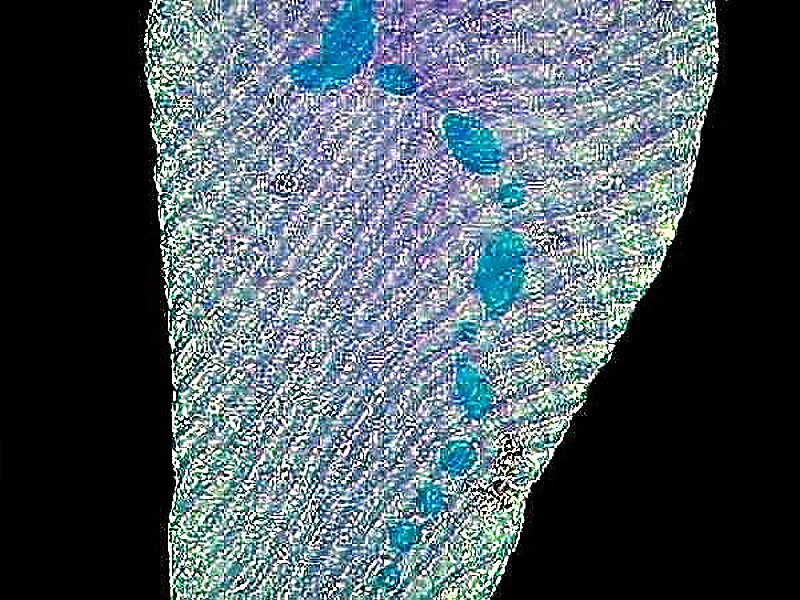

Now, I’ll show you a closeup of Stentor coeruleus which reveals the light pigment and the numerous fibrils. The macronucleus is a “beaded” or “chain” nucleus and its coloration, in this case, is due to my use of the nuclear stain Methyl Green-Acetic.

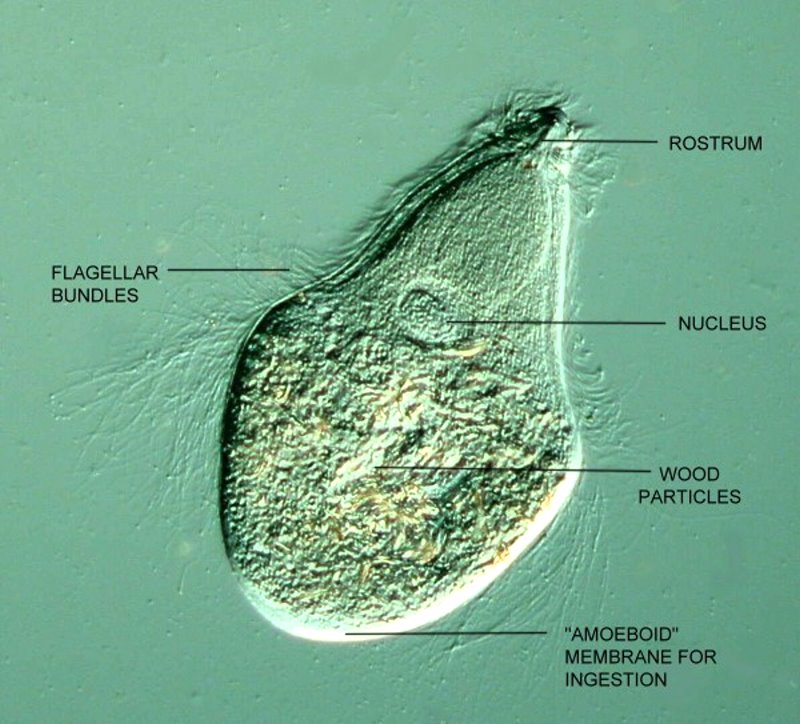

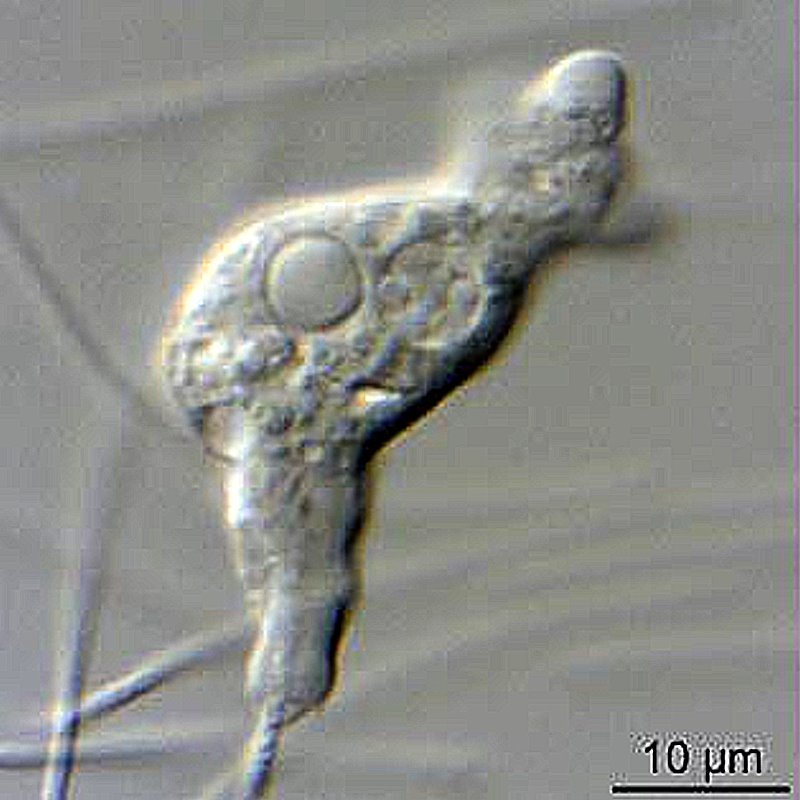

T is for Trichonympha. Trichonympha is a protozoan that belongs to the Order Hypermastigia; it possesses literally thousands of flagella, lives in the anaerobic conditions of the guts of termites, and, with the help of endosymbionts, digests cellulose, converting it into starches and sugars which the termite can metabolize. Without these and related protozoa, the termite would starve to death. The protozoa have a protected environment and a virtually endless supply of food.

The anterior end consists of a sort of “nose cone” called a rostrum, which has long, abundant flagella. The midsection is wider and has an abundance of medium length flagella which get very long at the end of the midsection and extend beyond the posterior end which is a wide blunt extension without flagella and which is soft and sticky. It is here that the ingestion of wood particles takes place! You’ve all heard of an upside-down cake; well, this is an upside-down critter. It “feeds” at the posterior end, but its morphology, arrangement of flagella, and hydrodynamics, dictate that the rostrum leads the procession when Trichonympha is swimming. However, getting a general sense of its shape is no easy, obvious task, since it possesses a highly flexible membrane which allows it to behave like a contortionist, especially under a cover glass.

First I’ll show you the organism in all its glory as photographed using DIC.

And as a sort of brief map, I’ll give that same image a few labels.

Finally, a closeup of the area around the rostrum.

U is for Urocentrum turbo. Now, we’re getting to that really difficult part of the alphabet where there are organisms that I have observed, but don’t have images of and, as a consequence, in several instances now, I shall have to rely on image and/or video clips from the Internet.

That is the case with this critter. I have observed it frequently, but trying to photograph it is a nightmare as you might gather from its species name. It is like a microscopic turbine. It is a rotund little organism with a pinched “waist” with ciliary bands. At its posterior end, it has a “tail-like” bundle of cilia which are capable of producing an adhesion which allows it to attach to substrates and then spin like a dervish. Here is a short video clip from YouTube showing that.

V is for Vorticella. This is another entertaining and interesting ciliate. It was first described by Leeuwenhoek in 1676. It is bell-shaped and has a stalk which is highly contractile when the organism is disturbed. It has a ring of cilia around the top area. If you look closely, you can see a fiber running through the inside of the stalk; this is the spasmonene (or myoneme) and is a highly complex apparatus. It coils and retracts the bell at great speed and energy. I will show you a specimen which is attached to a bit of debris and is extended.

W is for Willaertia. This is a tiny, free-living, thermophilic amoeba which has a temporary flagellar stage. I will have to give you an image from the Internet for this one.

Y is for yeast. This is again from the Internet and shows the yeast budding.

X is for Xanthidium, an intriguing little desmid. Back to the Internet for this one. It usually occurs in bundles of 2 or 4 and has spines radiating from the cells.

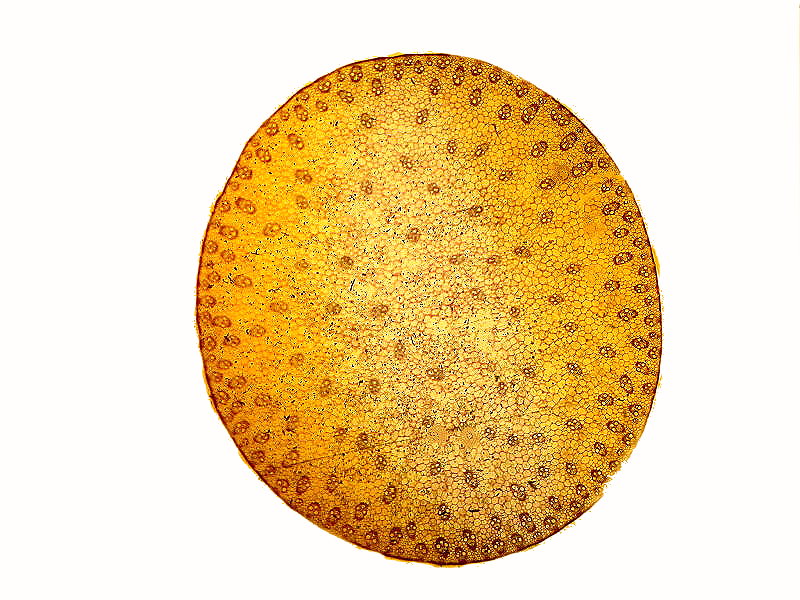

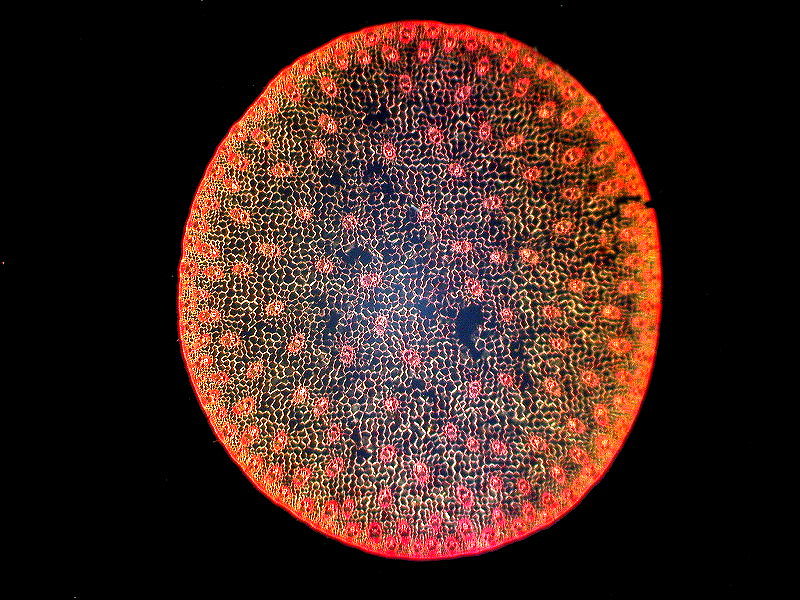

Z is for Zea mays. I could have stayed with micro critters and used Zoothamnium, a colonial peritrich in that group with Vorticella, however, I decided to climb up the ladder to a micro-section of the stem of a large plant, and go with Zea mays, which you may recognize as the common edible corn that’s “knee high on the fourth of July”–that is, if there’s no drought. So, finally, we’re at the very last 2 images. The first is a cross section of the stem in brightfield and then in polarized light to show you what wondrous results some specimens provide when so observed.

Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m exhausted from this alphabetical exercise; but don’t worry, I’m already recovering and planning a parallel alphabetical article on crystals in polarized light. So, have a good stiff drink before you start reading the new in one of the next few months. In the meantime, explore and write notes and articles and send them to Micscape so that I don’t have to keep going on in such a long-winded fashion.

All comments to the author Richard Howey

are

welcomed.

If email software is not linked to a browser, right click above link and use the copy email address feature to manually transfer.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the August 2022 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .