|

|

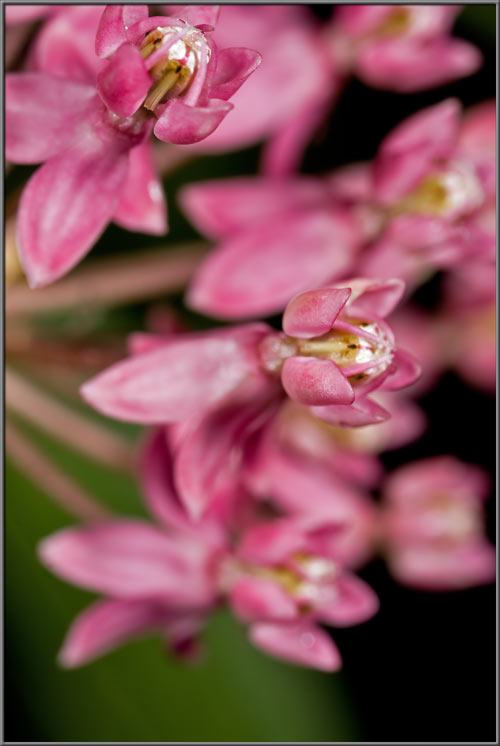

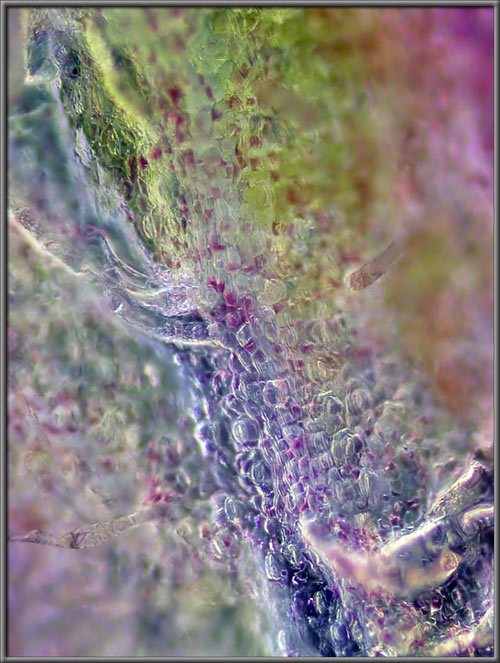

A

Close-up

View

of

a

Swamp Milkweed Cultivar

|

|

|

A

Close-up

View

of

a

Swamp Milkweed Cultivar

|

Published in the

August 2013 edition of Micscape.

Please report any Web

problems or

offer general comments to the Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine

of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .