A Dall-Type Diamond Microwriter

by Norman Groom, UK

Horace Dall was a slightly built man but a giant amongst those that new him. He was known in both the amateur and often in the professional world for his skills in optics, astronomy and microscopy. A search on the Internet under the name ‘Horace Dall’ brings up a wealth of information relating to his inventions and ideas. Horace died in 1986 which was a great loss to the world of astronomy and microscopy.

I was fortunate to have known Horace for some 20 years prior to his death and with a friend we used to visit him on many occasions as well as taking him to the Quekett Microscopical Club meetings during his later years.

In the 1980’s many enjoyable evenings were spent with him discussing matters relating to astronomy, microscopy and other scientific interests. Horace would discuss and demonstrate many of the ideas and projects he had worked on, virtually all of them trying to achieve the limits of what were obtainable during his lifetime. He was well known for many ideas and among his many well known inventions were the Dall Flow meter used in Industry, the Dall-Kirkham astronomical telescope, and the Dall null test for astronomical mirrors. Designs for other instruments and equipment have been reported in various scientific journals.

Amongst various projects discussed was his technique for producing diamond engraved micro-writings to be viewed under the microscope. I remember that we talked about many designs of reduction equipment made in the mid 19th and part way into the 20th century, usually based on large pantograph type reduction drawing equipment, to achieve microscopic diamond writings on 3” X 1” glass slides. There were several preparers of these slides. Some were simply distributed among friends or within societies but many were sold in the Victorian period as novelty items. The writings were not intended as test objects so in many cases were not the smallest achievable as they had to be viewed readily at lower power, higher powers not always being available to amateur microscopists. The other factor was that the smaller the writing the more expensive the slide.

All of these micro-writer machines relied on the lever principle. If a writing diamond was, for example, mounted a quarter-way from the pivot point along a pivoted arm, the end movement of the arm would be reduced at the diamond writing point by a factor of four, the ratios of the length of the arm to the distance of the diamond to the pivot point. If larger ratios were required, above say one hundred to one, then the length of the arm would become almost impracticable. An improvement on this by using a compound arm, i.e. one arm driving a second arm, gives a more compact arrangement with the overall reduction equal to the product of the reduction of the individual arms. Even this improved equipment could still be of considerable size in order to produce the large reduction desired. Errors due to flexibility, the physical size, play in the pivots used and other factors limited the reduction that could be achieved but even so letters as small as 10 microns could just be achieved.

My own interests were in both astronomy and microscopy but in the 1980’s microscopy was the greater interest, probably due to the weather conditions in the U.K. I had already mastered the art of making microphotographs (Ref 2) as well as having some success in making arranged diatom and butterfly scale slides and micro writing to me was the next challenge.

Horace was very generous with his ideas, especially to those that had interests like his own and had no commercial interests. He happily described his own design and like many of his inventions it was simple, eliminating the errors that may have occurred on the earlier machines. His own machine was based on sound engineering principles and is credited with producing, to my knowledge, the smallest diamond writings then known with letters of one micron or less.

After describing this equipment to me we went up into his loft to try to find his original equipment but all we could find was the base board with one or two parts still attached. His own micro-writings were made in the 1940’s (Ref 1). Judging by the remains of the equipment he had never used it since but it appeared that it had been partially stripped down to use the parts for other projects. This was typical of Horace because having achieved the ultimate limits on one project he would soon be working on the next. Horace never mentioned that anyone else was attempting micro-writing at any time since his work in the 40’s and he would certainly have told me if he or anyone else had ever made another micro-writer based on his principles.

Horace was always encouraging others to attempt the impossible and had a saying ‘If someone tells you that something is impossible, what they mean is they cannot do it’. Not only did Horace supply me with all the design principles needed to construct my own micro-writer but gave me a small quantity of industrial diamond to enable me to select a splinter of diamond suitable for use on the machine. He described the construction of the equipment in sufficient detail to allow me to design and construct my own micro-writer based on his design. Following the construction and use of my own machine and after his death, I was asked by an acquaintance who was already making arranged diatom slides, to make a second machine. This I did in exchange for some one or two of his slides. I suspect that the second machine was never used and I do not know if it is still in existence. I never saw Horace’s machine when it was complete, so it is impossible to make a comparison with my own, certainly the materials available in the 1980’s and the 1940’s would differ considerably. Unfortunately Horace became ill soon after the construction of my first machine and died in 1986, before I constructed my second machine from other materials to hand. From memory I do not think he ever saw my first version or the writings I had made.

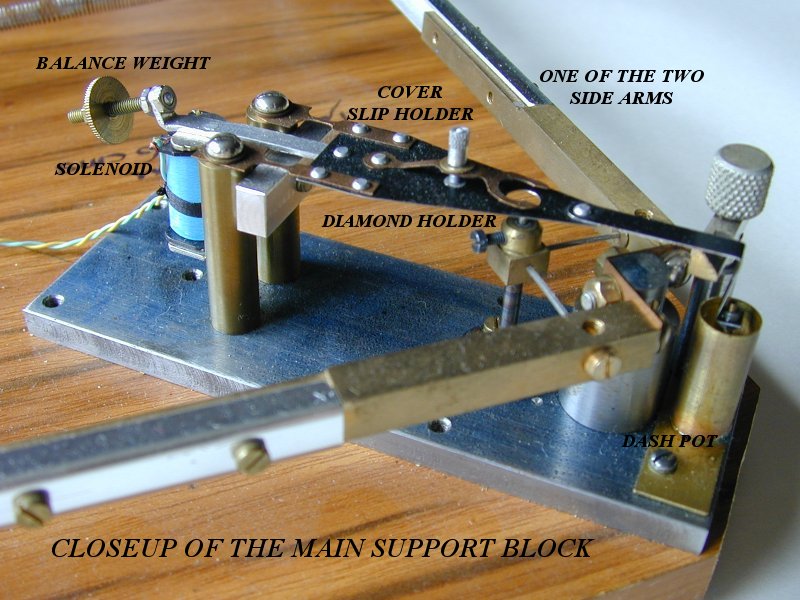

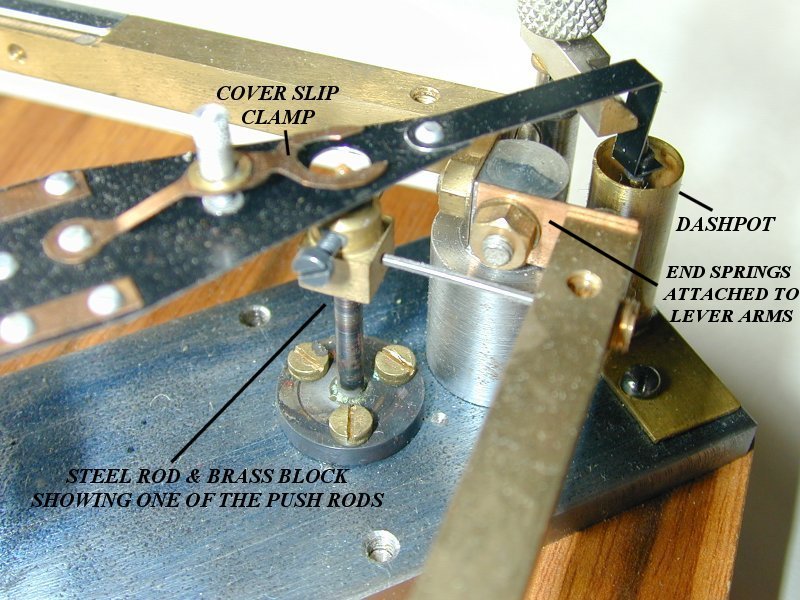

In Horace’s design the diamond writing is carried out in reverse on the underside of the cover slip rather than on the 3” X 1” slide itself. The cover slip is lowered onto the diamond, the slip being held in a fixed horizontal position in a balanced and very lightly constructed arm. The diamond writing being only a micron or two high requires a high power oil immersion microscope to see the final product properly and any excessive space between the writing and the front lens of the objective would make the use of oil immersion almost impossible. To protect the fine diamond point when contacting the glass cover slip a dash pot is required. This is a light weight piston fitted to the arm holding the cover slip, the piston being immersed in an oil filled cylinder that allows the arm holding the cover slip to be lowered slowly onto the diamond or raised carefully from the diamond after that section of the writing or a word is completed. Some means must be available of course for lowering and raising the arm and in my own case I used an electrically operated solenoid to carry out this function whilst Horace would have used some unknown mechanical arrangement.

Description of my machine.

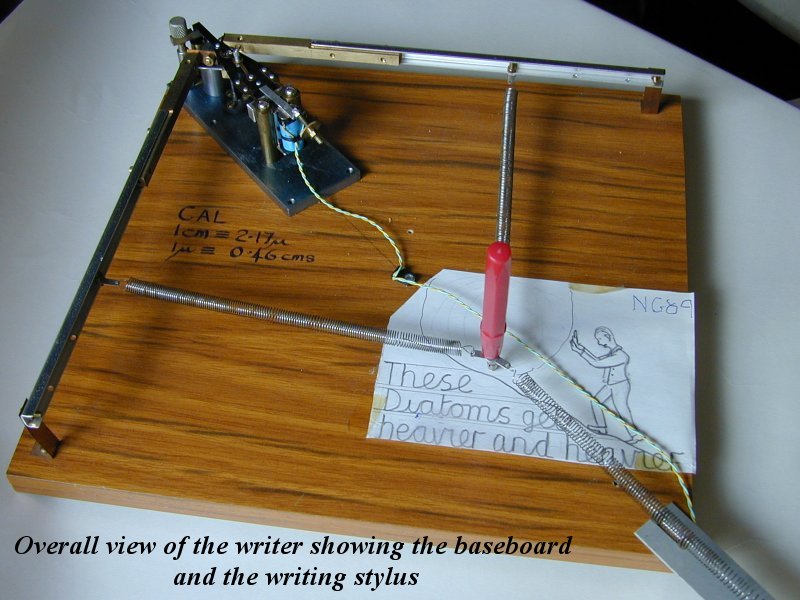

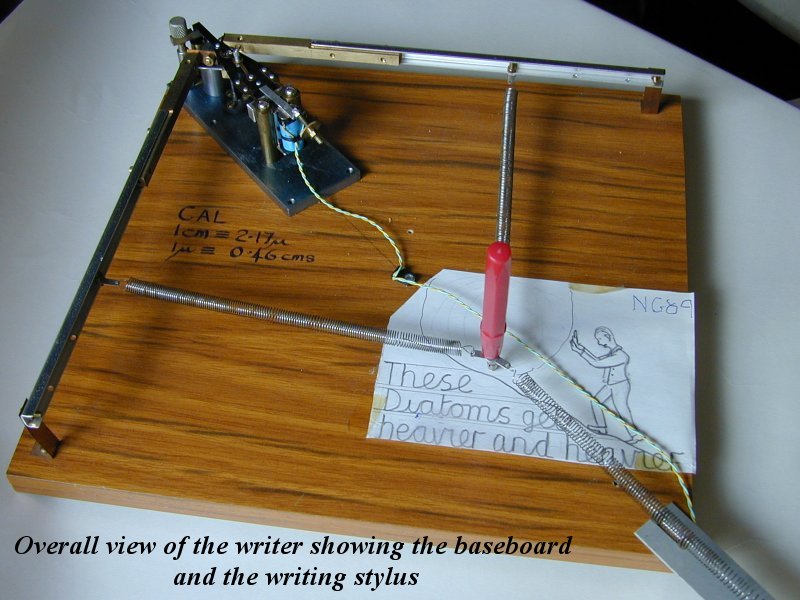

The writer is mounted on a chipboard base about 30 x 30cms (12” X 12”) that acts as the writing tablet and carries two arms joined by a spring bearing in one corner. The precision part of the writing apparatus is mounted on a steel plate fixed to the base in the same corner. The base board itself plays no part in the writing process, it only acts as a support for the arms which are held in place by 3/8” wide Beryllium Copper leaf springs and it also locates the writing point in an appropriate position by three quite weak and balanced coil springs, two of which are attached to the arms. The beryllium copper strip was ‘banding’ strip used to hold English Electric ‘C’ core transformer cores together and used extensively in the 1980’s. It was a valuable source of springy material and used extensively in the micro writer.

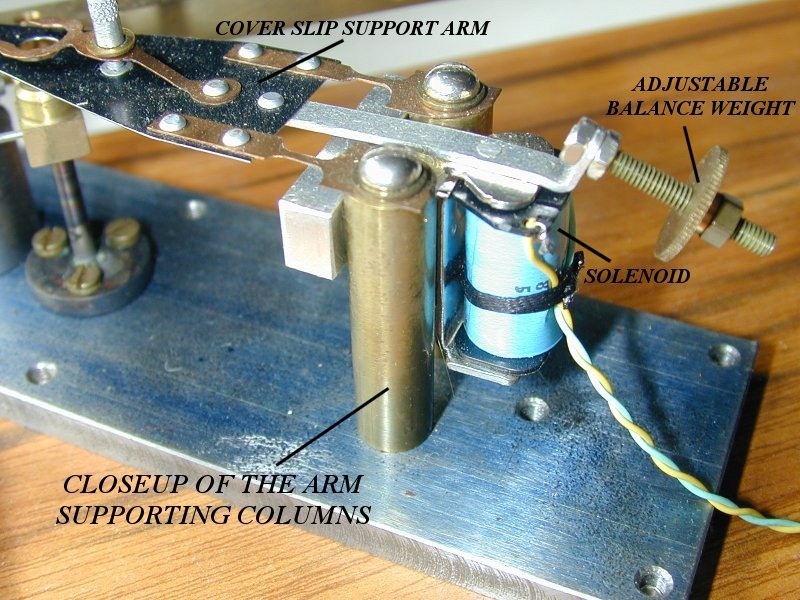

The precision parts are mounted on a 5” X 2” x Ľ” steel base plate. This base carries the bearing for the two arms, the oil-filled dashpot, the two supports for the arm that hold the cover slip and the solenoid that raises and lowers the arm' the solenoid coming from a dismantled low voltage relay.

The corner bearing support is a 1” aluminium block with flats milled at 90 degrees. Leaf springs are bolted onto these two faces, the other ends of the leaf springs being attached to the ends of 5/16” square bars forming part of the two arms. The diamond is mounted on the tip of a 1/16” diameter copper pin fitted vertically into a 5/16” X 5/16” brass block. The pin holding the diamond is held by a 6BA screw such that the diamond can be easily replaced if damaged. The brass block is silver soldered to the top of a 1” X 1/8” piece of silver steel rod, this in turn being silver soldered into a substantial steel disc at the bottom. The whole assembly, i.e. the pin holding the diamond, the brass block, the flexing silver steel rod and the mounting block, is then screwed rigidly to the base plate so that the only possible movement of the diamond is through the flexing of its mounting rod.

Movement of the writing stylus causes proportional elastic flexing of the vertical silver steel rod and hence reproduces the writing on a much reduced scale. The arm that carries the cover slip is attached to the supporting pillars by two very narrow Beryllium Copper leaf springs, the arm being counter balanced by a screwed weight running on a piece of 6BA threaded rod. The counter balance is needed to protect the diamond from excessive pressure on the point during engagement. A tiny steel disc riveted to this balance arm is pulled down magnetically by a solenoid located on the supporting columns. The very front of the arm, which is made of thin but hard anodised aluminium, is bent down at the end and carries a small disc immersed in the cylinder holding the damping oil. The hard anodised aluminium used for the arm was obtained from scrap Polaroid film containers used in industrial Polaroid cameras.

The two arms attached to the corner bearing only move by a few microns during writing process and their movement is carried through to the brass block that holds the diamond mounting pin by two push rods, at ninety degrees to one another, pointed and inserted in small indentations in both the arms and the brass block. The indentations in the two arms are set in two screwed plugs allowing for some adjustments to be made. The tiny load transmitted by the springs via the arms, flexes the silver steel rod, sufficient to follow the movement of the writing stylus and thus impart the writing onto the cover slip when it is lowered onto the diamond.

The machine as described is capable of writing letters only one or two microns high but was not designed to cover large sections of writing. There is some small curvature in lines of writing but my machine was designed to see how small diamond writing could be made rather than writing a larger amount of text. A simple test writing of a grid of lines would demonstrate the non linearity that can occur. To see the finished writing easily it helps to use oil immersion both on the objective and the sub-stage condenser of the microscope, especially if the letters are below 2 microns. With writing this small it must be appreciated that the grooves that make up the writing are extremely fine. Black Lead was traditionally used as infill in writings which for this application the Black Lead has a too coarse a grain structure. If these fine grooves are to be made visible they have to be filled with some form of grain-less dye that has a reasonable density. Horace spent some time on this investigation and came up with a solution; it was to use the ink from Bic Biro pens. The other problem arises that if the slides are not stored in the dark the ink can bleach out with time, making the writing almost invisible.

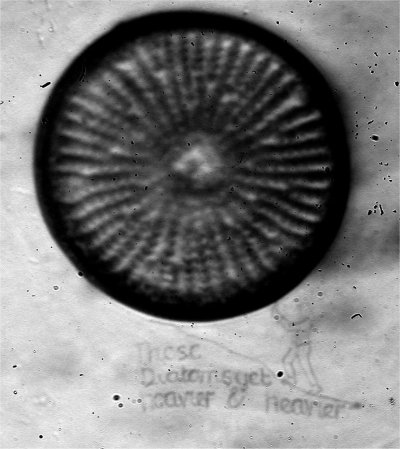

The engraving of the master drawing shown in the first figure was executed in 1989 and a recent digital image is reproduced in the following photograph as seen using a x40 dry objective with a x10 eyepiece and a further x1.6 from the binocular head. A stage micrometer calibrated to 100 micron divisions provided new estimates of 76 microns for the diameter of the diatom mounted in position on the slide and a height of 3 microns for the lower case letters in the text. Visual contrast under central stop illumination is better than as reproduced here and could be enhanced even further using, for example, oil immersion or possibly phase contrast. With this particular diamond point the scale of the master drawing could have been reduced to give individual small letters less than 2 micron in height whilst still retaining legibility.

The task of creating micro-writing involves much more than placing a cover slip on the writer and moving the stylus to follow the large scale text. The key to success is in the end patience and perseverance and the ability to handle delicate equipment. Previous experience in making arranged slides is also an asset. The diamond has to cut a grove probably only 0.1 micron wide and deep and the job of first selecting the diamond and adjusting the working pressure cannot be over emphasised. The diamond is the crucial item within the system. It is selected by crushing some industrial diamond and selecting a suitable point under a high power microscope. One has to remain perfectly still whilst carrying out the writing operation apart from steadily moving the stylus with the right hand and operating a small solenoid switch with the left hand to raise and lower the cover slip at the appropriate time.

Having succeeded in producing the writing, the first task is to find the writing on the cover slip and due to its tiny size it is like finding a needle in a haystack, especially has it has not yet been filled with dye. The next procedure is to ‘ring’ the writing so that it may be easily found again. It is then filled with dye by rubbing the dye over the surface and removing the surplus with a new razor blade. It is then mounted dry, on a ring of cement on a standard slide. One or two of my own writings involved placing a diatom near to the writing to demonstrate its size, after the writing was completed. My own diamond writer followed Horace’s layout, with spring pressures adjusted to produce the minimum size letters possible. I do not think I ever achieved quite the size Horace achieved but then I did not have the quality of the microscope that Horace had to see the final result. There is no reason why the machine could not be redesigned by varying the spring tension or the size of the rod supporting the diamond to give larger scale writings whilst still following the principles that Horace had laid down.

The machine is relatively simple to manufacture, anyone with model engineering experience could make one but using one is a different matter. I would advise anyone attempting micro-writing to first gain experience in making arranged slides using diatoms or butterfly scales. Also one needs a microscope capable of resolving micron-size images. Starting with diatoms or butterfly scales is a great way to learn how to work in the ‘small’ world. Selecting and mounting the diamond is not dissimilar to sticking a diatom on the top of a pinhead.

It was a great loss to many of his friends when Horace died in 1986 and I only regret that I did not have more time to discuss the matter in more detail with him. The only Horace’s diamond writings I know of are held at the London Science Museum and are dated in the 1940’s (Ref 1). The questions I still have are, did Horace carry out any writings after that date and if so when and where are they? Was Biro ink available in the mid 1940’s if not what did he use to fill his writings? He certainly told me about the ink when I spoke to him in the 1980’s. If anyone has any further information regarding Horace’s work relating to micro-writing I would be pleased to hear from them. It is some years now since I have used the micro-writer, the last time in about 1989 but coming across it recently in a storage box once again raised my interests and hopefully when the winter weather arrives I will try to get the writer operational once more. With the Internet now available I thought it is the ideal time to let others know more about the incredible world of Horace Dall.

© Norman Groom 2009

Comments will be welcomed by the author.

References

1) Diamond Writing 1853 - 1946, Brian Bracegirdle & Stanley E Warren, Quekett Journal of Microscopy 1996, issue 37, part 8, pp: 621 – 632

2) Microphotography - The Making of Microscopic Size Photographs by N G Groom. Microscopy, 1986, 35 (6), pp.445-450. (A modern practical guide to making microphotographs on microscope slides).

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the August 2009 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net .