|

A Trip Into The Past: Part 8 by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Part 1 : Part 2 : Part 3 : Part 4 : Part 5 : Part 6 : Part 7

I did come across another issue of The Taxidermist , Vol. I, No. 2, August 1892. I’m not going to discuss the articles nor natter on about the advertisements; I’m just going to share a few helpful hints provided to make your own ventures into taxidermy less difficult. They are very brief and we shall quickly move on to other magazines.

For

those of you mounting alligators, I’m certain it will be

invaluable to know that: “An alligator can be skinned only as

far as the occipital

bone.”

For the

ornithologically inclined: “Corn meal is a better absorbent to

use in skinning a bird than

plaster.”

And we

mustn’t neglect the mammalogist: “All mammal skins ought to be

well tanned in a brine of alum, salt, and saltpetre to set

before they are

mounted.

Finally,

for those of you who want to create landscape settings for the

mounting of your animals: “Artificial snow can be made by

crushing burnt alum with a

roller.”

You may recall that in the previous part, we found a notice

in

The West American

Scientist

that James P. Babbitt of Tauton, Massachusetts had suffered a

devastating fire, but now

in

The

Petrel

, Vol. 1, No. 1, January 1901, we find that he has apparently

recovered and rebuilt, for he is once more offering a wide

range of items for the taxidermist and

naturalist.

Moving on to yet another, and earlier publication, The Stormy Petrel of which I have Vol. 1, No. 3, June 1890 and Vol. 1, No. 5, August 1890, on the back cover of No. 3, we find an advertisement for The Farrago : “A monthly Literary Magazine for Boys and Girls, and one pound of well assorted Reading Matter for $1.00.” If, however, you were willing to forgo the extra pound of assorted stuff, you could get a year’s subscription to The Farrago for just 35 cents. The word “farrago” initially makes me think of a confused collection, a hodgepodge, but I take it that the publisher of this magazine intended it in its other sense of being a medley. I wonder what the assorted pound of reading material was like. I remember years ago, being in a very large, cluttered, and eclectic used bookstore in which the owner had come up with the clever notion of selling off his dross at $1.00 per pound. It’s absolutely amazing what people will buy when they think they’re getting a bargain. The front cover of this issue has a poem titled The Stormy Petrel without identifying the author which may convey to you something about the quality of the verse.

The front cover of No. 5 has a depressing, morbid poem titled: “On A Goldfinch” by William Cowper (pronounced “Cooper” I am told by one of my learned colleagues) whose work I was familiar with from a peculiar and rather boring little book called Table Talk which I had purchased as a guileless youth.

This

issue of the magazine has 6 items of special interest; 2

advertisements and 4 brief notes. Let’s consider the ads

first. M. Smith & Co. of Mendota, Illinois (not exactly a

coastal city) offers you the special opportunity of acquiring

leopard shark’s eggs for a mere 15 cents each. We are informed

that: “A curiosity collector should not rest nights, until one

of these eggs are [sic] in his cabinet.” At last, an

explanation for my

insomnia.

The

second ad is from the San Diego College of Letters which

already back in 1890 was employing clever marketing

strategies.

“The

Attention of parents is especially directed to the climatic

advantages enjoyed by this institution. Students unable to

attend schools in more rigorous climates, or too delicate in

health, may study here regain full health and compete in

scholarship with their stronger

associates.”

This

makes one wonder whether the institution was a college or a

tuberculosis sanatorium. In 1890, the air was probably clear

and clean; however, in 1960 when my wife and I moved to Los

Angeles to do graduate work, there were days when, in the

civic center, one couldn’t see the tops of the buildings

because of the smog. In fact, we would wake up in the morning

and hear the birds coughing. San Diego’s air may be marginally

better, but one has to remember that it is an enormous port

city with pollution not only from cars, but refineries, heavy

industry, and ships. Such a notice today would be blatant

false advertising of the most egregious

sort.

Today, there is much talk about urban myths, but in the 19th Century, one was just as likely to encounter rural myths. This first one is brief enough to quote in its entirety.

SQUIRRELS CROSSING RIVERS

Squirrels

will sometimes migrate from one place to another by the

thousands. It is said that neither rocks, nor rivers, nor

forests, nor mountains will stop them. If they find a river

too wide for them to cross, they will go back into the forest

and provide themselves with a piece of bark, and then they put

out to sea, making their tails serve as sail or rudder. It

often happens that they ventured too far, and cannot contend

against the waves, and therefore never reach the other

side.”

If in

1890, there had been the equivalent of the National Enquirer,

I would expect a

headline:

ATTACK SQUIRRELS BUILD BOATS:

INVADE MANHATTAN

Imagine

a squirrel using its tail as a

rudder!

The

second note also contains a couple of points which strain

credulity. The topic of the paragraph is strange marine fish.

The halibut’s strange feature of having both eyes on one side

of its head is mentioned–“a fish sometimes six feet long”.

Then, we are told that the much larger sword-fish–“often 20

feet long–sometimes attacks the side of a ship and runs its

sword deep into the timbers.” Now, swordfish are indeed

powerful, formidable creatures, but I suspect it is only

retarded specimens that attack ships. However, the next

example is a first-class aquatic myth. “The cuttle-fish has a

roundish body, a wicked-looking head and face, and eight long

arms, with which it catches its food, and has often been known

to catch sailors and squeeze them to death.” For starters,

whoever wrote this was apparently thinking of an octopus,

since cuttlefish have 8 arms and 2 longer tentacles, as do

squid. Further their body is elongated. Giant squid and octopi

devouring sailors and even pulling down entire ships are

classical parts of mariners’ lore. I vividly recall an old

drawing of a three-masted ship around which there were

gigantic tentacles extending up to the top rigging, pulling

the unfortunate vessel down into the

sea.

There

are indeed some giant squid, but they have turned out to be

quite elusive and scientists have been spending a great deal

of time and money trying to film and capture these fascinating

creatures. They are, of course, not so large that they would

attack large ships and they seem to be rather shy. Most large

specimens of cephalopods that scientists have been able to

study closely have been washed up on beaches. If a large

octopus were to attack a human, the greatest dangers would

be:

1) drowning from being held under water and 2) rending of the flesh by the powerful “beak” which the octopus uses for attacking and dismembering prey. Incidentally, there is in Australia, a small blue octopus which possesses a very dangerous toxin, but this doesn’t fit into the giant monster-of-the-sea myth. Our reporter tells us, however, that these great creatures often squeeze sailors to death–to which I reply–Yes, and Jonah was swallowed by a whale.

The next

little note is titled: “The Economy of Nature”. We are told

that a German professor spent 20 years studying a certain

snail “and learned this interesting fact concerning it.” (For

20 years of research, I hope he learned more than one fact.)

Unfortunately, we are not given a clue as to the identity of

this unusual gastropod. We are told that it occurs in coastal

areas on both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The intriguing

fact in the account is this: the Pacific snail is the prey of

“a certain fish” and so has evolved a third eye on the back of

its head. The predator fish is absent on the Atlantic coast

and so these snails have no posterior

eye.

I know

that nature produces incredible numbers of astonishing

adaptions and many of them seem so bizarre that, without

documentation, they seem hard to believe. I wish the anonymous

author had supplied a bit more information so that one could

track down this unusual

gastropod.

One of

the reasons that I find some of these accounts suspect is

amply illustrated in the next brief

note.

“A LIVE

SEA-FLOWER, named the opelot, which looks a good deal like the

China aster, is found blooming in the ocean. Its petals are

light green, glossy as silk, and each one is tipped with

rose-color. Little fish which are pleased with the bright

color of these waving, silky petals, swim around and look at

them. Soon one swims nearer and touches the rosy tips, when a

sharp pain goes through it, and in a few minutes, it turns

over and dies. It has been poisoned...The petals then prepare

to catch another; and so that plant lives and blossoms, fed

from the fish it catches so

strangely.”

I’m sure

that you have all figured out by now, that this organism is

not a plant at all, but a sea anemone and, of course, its very

name invites us to be misled. Apparently Edmund Gosse’s

beautifully illustrated work on anemones had not yet reached

Mendota, Illinois and today if you want a copy you’ll have to

pay anywhere from $185 to over $1,000! As an aside, I Googled

the term “opelot” and got pages of entries in Polish along

with a few in Russian and German. So, I have no idea where

that term came from. The conjectures in this little note,

though quite wrong, are understandable. There are

insectivorous plants that depend upon the animal kingdom for

nutrition and there are plants that exude some nasty

toxins–poison ivy and nettle being two common examples.

Nonetheless, were you to take this account as given, you would

be seriously misled. such errors have a very long and, one

might even say, distinguished history, since Aristotle, the

first real biologist thought that some kinds of sponges and

tunicates were

plants.

Next, I

would like to look briefly at several intriguing articles and

one advertisement in The Western Ornithologist (formerly The

Iowa Ornithologist), Vol. 5, No. 1, January-February, 1900,

published in Avoca, Iowa. I mentioned in a previous essay in

this series, that it was traditional in the period for

publications to offer premiums to entice subscribers and this

magazine was no exception. In a full page ad, one was offered

a choice of three premiums for a subscription, the price of

which was 50

cents.

I. 50

envelopes with your name and address bronzed in

the

corner.

II. 100

datas, size 3x5

inches.

III.

Your choice of any 6 of 26 Cuban views, size 2½ x 3¼

inches.

I won’t

bore you with the entire list, but I’ll give you a few choice

examples of these Cuban views, using their

numbers:

1.

Turkey Buzzards in the suburbs of a city (poor

negative).

8.

Driveway to a country

residence.

12.

Tombs in cemetery at Neuvitas,

Cuba.

15.

Block house, forming entrance to

dungeons.

21.

Cuban ox

cart.

16.

Cubans paving the

streets.

Who

selected these pictures–El

Sade?

I’ll

certainly want #13 to add to my collection of places of

execution and #1 for my huge display of photographs of turkey

buzzards. The more I know of humans, the less I understand

them.

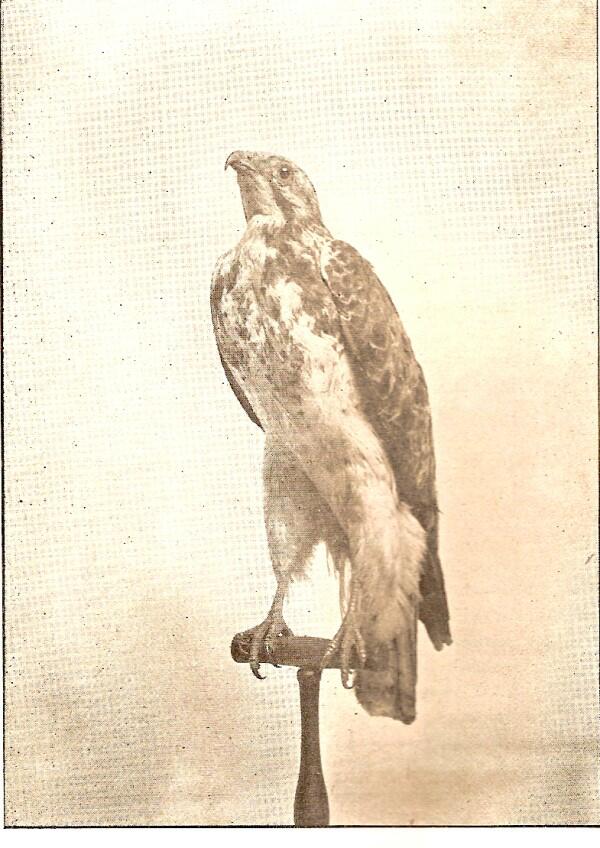

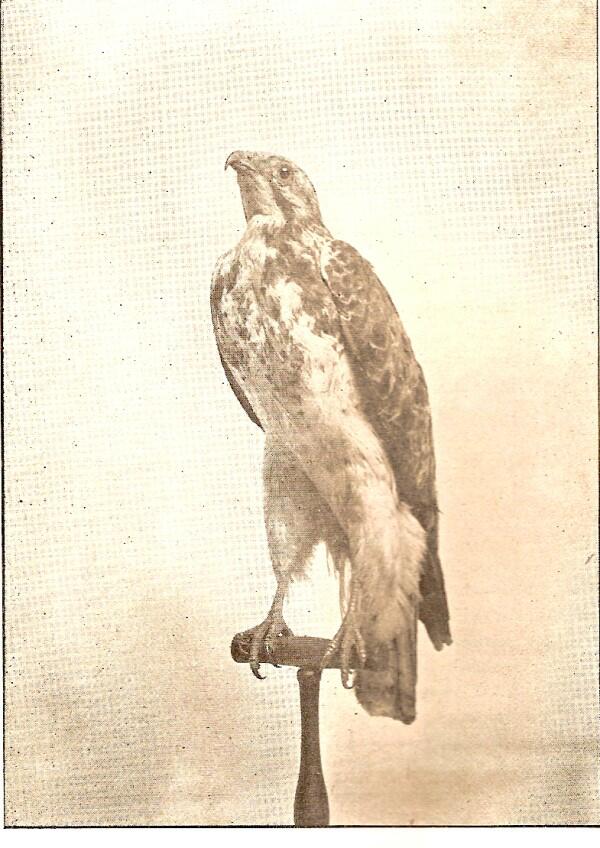

Actually

all of the articles in this issue are interesting and

well-written and there are some excellent drawings and a fine

photograph of a Swainson’s

Hawk.

The

article “Bird Life In The City” by Burtis H. Wilson is full of

interesting observations about both humans and birds. In the

first paragraph, he comments: “In the midst of the hurry and

bustle of life at the close of the nineteenth century, with

all the varied pursuits which go to make up the round of

existance [sic], it seems strange that so many people can find

time to take an interest in

ornithology.”

Oh, what

a difference a century makes! Since this was published in the

January/February issue of 1900, Mr. Wilson probably wrote this

in 1899. To us in 2007, it seems almost laughable that he

speaks of “the hurry and bustle of life”–no radios, no

televisions, no computers, no cinema, no bus lines, no

airplanes, no telephones, very limited electricity, limited

indoor plumbing (certainly in Iowa), no stereos, no cell

phones, no electron microscopes, and the list goes on. In

1900, many of the “labor-saving” devices we have now were not

yet invented and many tasks took much longer than they do now.

Yet, with all the distractions, many Americans are working

more hours than they did 25 or 50 years ago; parents organize

their children’s activities in team sports, dancing classes,

piano lessons, beauty pageants, and God knows what else.

Communing with nature has been redefined as taking your kids

to the park for soccer practice. “Roughing it” now often

amounts to loading up granny and the kids in an RV the size of

a Greyhound bus–with TV, DVD, stereo, cellphones, wireless

lapdog (sorry, laptop) computers, toilet, kitchen and

bedrooms–to go “plug in” at a campground in Yellowstone and ,

if you go in the winter, you can tow your snowmobiles behind

and then when you get there, you can ride around deafening all

the grizzlies, elk, antelope, and

skiers.

As you can tell, I have mixed feeling about all of these technological “advances” which we enjoy. Most of my reservations have to do with the fact that we have not, for at least two generations, taught either young people or adults how to properly utilize the magnificent resources at our disposal. I know of a beautiful spot 15 miles east of Laramie in the mountains. It is not easily accessible; there is a lovely little spring feeding a stream where I have found Lacrymaria and Planaria, a series of beaver ponds filled with wonderful micro-life, including the bryozoan Plumatella repens , pine and aspen groves surround the area, and I have found prickly pear cacti with their yellow and red flowers, a hummingbird’s nest with 2 tiny eggs, ducks on the pond, aluminum beer cans, styrofoam, plastic sacks, newspapers, condoms, a rusty knife, and other detritus of indifferent humans.

For many

dwellers in large cities, avifauna to them means pigeons which

are widely despised. In smaller, less populated communities,

there are still bird watchers and even clubs and many

individuals keep “life lists” to record every species they see

in their lifetime. I am fascinated by birds, but I am not O.O.

(ornithologically obsessed), but I must admit that in the

spring I look forward to driving out to some of the isolated

lakes where my only other human companions will be a few

fishermen basking in the silence and there I encounter blue

heron, pelicans, Canadian geese, red-wing blackbirds,

yellow-wing blackbirds, red-tailed hawks, occasionally an

eagle, and many busy little American avocets skittering around

the edge of the shore, probing the sand with their long beaks.

Here, in these special, secret places, there is a kind of

peace which allows me to lose my ego and expand out into the

immensity around me. There is a mixed sense of joy and

loss–joy in the freedom, a quickening of my senses, a

celebration of being both mind and body; loss, in the

realization that I have to return to a context of

responsibilities and obligations. I feel sorrow for the

technocrats and techno-teens who are either indifferent to

nature or know it only through television nature programs or

zoos.

Back to

Mr. Wilson’s essay. He, like many sensible persons of the

period, advocated responsible collecting of

specimens.

“

Of course these collections are of help to the real student,

as is also a scientific knowledge of the birds’ classification

and physical structure, but to the average observer they are

not necessary. And it is to this latter class of observers,

and they are far more numerous than the former, that this

article is addressed. The collection of eggs and birds is well

enough when it is done to add to one’s knowledge, but when, as

is usually the case, it is taken up in the same spirit as the

collecting of stamps or coins or autographs, merely to satisfy

the collector with the possession of them till he grows tired

and turns his attention to collecting something else, the true

bird lover will do his utmost to discourage

it.”

It is

discouraging to think of how many individuals end up

discarding natural history collections of all kinds, but even

more discouraging how high schools, colleges and universities

also either discard collections or let them fall into neglect

and no longer use them for instructional purposes. This is one

of the splendid things about the internet; it provides an

opportunity for the recycling of specimens. Last year on eBay,

I bought some wonderful Morpho butterflies which had been

mounted in the 1920s. Just last week, I bought some slides of

parasites from a scientist who is retired and wants to allow

others access to some of these unusual

organisms.

Several

years ago, I offered to donate to the university here a fairly

wide variety of duplicate preserved invertebrates. I was told,

rather bluntly, that using funds to maintain such a collection

was not a high priority. This experience got me to thinking

that it may well be better to offer such items for sale rather

than donate them since, if an individual is willing to spend a

modest bit of money to acquire them, then perhaps he or she is

more likely to make use of them than an institution

is.

Wilson

has some keen observations regarding how man’s intrusion with

his city-building has provided new options for birds in terms

of nesting. He remarks that the Purple Martin which

traditionally nested in cliff crevices now nests “in crevices

under the cornices of city buildings and in spaces between the

iron beams in the tops of bridges.” Chimney swifts have often

moved from hollow trees to–where else?–chimneys. The Night

Hawk moved from the bare ground or rock to the flat gravel

roofs of

buildings.

Equally

interesting are his reflections on the use of materials for

nest

building.

“

Not only has the location of nests been altered, but the

materials used in their construction have been changed from

natural to manufactured. For instance, paper, twine, hemp,

yarn, wire, and even lace are found in the nests of many

species.”

It is

rather a nice thought that our avian friends are recycling

some of our detritus. He further comments that our invasion

has provided a shift in food habits of many birds which “feed

almost exclusively on cultivated fruits and grains, and

insects that infest

them.”

Mr.

Wilson is clearly a keen observer and a devoted lover of

birds. His essay is largely directed at city and suburban

dwellers in an effort to encourage them to develop an interest

in the avifauna around them and to help protect and preserve

them. He also is disturbed by the wanton destruction of birds.

“Just across the street from the orchard a Bohemian Waxwing

was shot one November day in a mountain-ash tree by a boy with

a sling-shot. As far as is known to this writer this is the

only one of the species ever taken in the county.” The very

crafting of that first sentence reveals the expression of deep

sentiment verging on a brief

elegy.

Two

other articles, one by a man and one by a woman, express the

melancholy of winter in the beginning of the year. In the

first paragraph of his piece, “A New Year’s Day”, David L.

Savage

says:

“ANOTHER

year drops into the gulf of the past. The faces of the crowd

are all turned toward the future–mine ever toward the past.

Everyone smiles upon the new year; but, in spite of myself, I

think of her whom time has just wrapped in her winding sheet.

The past year! At least I know what she has, and what she has

given me; whilst this one comes with all the foreboding of the

unknown. Is it storm or is it sunshine? Just now it rains, and

I feel my mind as gloomy as the

sky.”

However,

he then hears the song of a Slate-colored Junco and

experiences a rapid transformation of mood. “This unexpected

soloist dispelled, as with sunshine, the kind of mist that had

gathered around my mind...A happy man is the bird-lover;

always another species to look for, another mystery to

solve.”

For

many, the long, bleak winters of the Midwest with their brutal

cold, howling winds, heavy snows, and seemingly endless days

of overcast skies were oppressive and depressing. Nonetheless,

the bird-lovers seemed to be able to maintain a special

reserve of emotional strength which allowed them to transcend

the gloom and rejoice in the wonderful small pleasures of

life.

In “A

Winter Reverie”, Mrs. Mary L. Rann presents us with an account

that parallels that of

Mr.Savage.

“Slowly,

silently, like the fluttering down of gold and crimson leaves,

do our summer guests gather for their long journey home. The

summer is ended, say we; the harvest is reaped and garnered.

We enclose the field glass and put aside notebook and pencil

till another season...As we reflect upon the unkindness of the

season, we turn to our bookshelves for solace,...But suddenly

the glint of a wing or the clear call of some winter-loving

bird remind us that on the sunnyside of yonder hill are

gathered Juncos, Canadian Tree Sparrows, Tits, and Chickadees,

and across the ravine in the grove, may be found Nuthatches,

Creepers, Jays, Crows and purchance [sic] a Robin or two

attempting to brave an Iowa

winter.”

In my

view, Mr. Savage and Mrs. Rann are wonderful examples of the

virtue of having a passion for some aspect of natural history

and it need not be birds. Over the years, I have accumulated a

considerable collection of preserved organisms, both marine

and freshwater and I maintain a few plants, small aquaria and

cultures, so that when the weather is such that I can’t get

out, I always have material to study and wonder at. Actually,

today is a good example. It’s 3:00 in the afternoon and the

temperature is 5 degrees F. and there is lots of snow and ice

on the ground and the

streets.

I was

amused by one paragraph in Mrs. Rann’s essay wherein she

indulges in some moralistic anthropomorphic

projections.

“There

is no more interesting study than the character of birds. One

sees the frivolous, the gay, the stupid, the shy and

apprehensive, the stolid and indifferent, as well as the high

bred and aristocratic. There is also the cruel murderous

character in birds, as well as in the human race. We learn to

love birds by their character or otherwise. The lack of

tenderness of the Rose-breasted Grossbeak destroys my pleasure

in his beauty and in his song. A bird that is so indifferent

to the comfort of its young as to build its nest of dead twigs

in an open slatternly manner, without lining of any kind, has

the instincts of the

aborigines.”

One can

almost see Mrs. Rann quivering with outrage as she pens these

remarks.

Almost

every summer, I find a few feathers scattered in the yard

which are, I suspect, the result of birds squabbling over food

or nesting territory. Feathers are remarkably complex

structures and can prove hours of challenge in the attempt to

unlock some of their secrets. In this issue, Mr. Morton E.

Peck examines the plumage of the Blue Jay. This is the first

of a series of articles in which he rather ambitiously

proposes a “comparatively full survey of the plumage of a

single representative bird as illustrative of the whole avian

class.” He adds that he will not address the issue of

coloration and admits that he has selected the Blue Jay

because it presents “no striking peculiarities of feather

structure.”

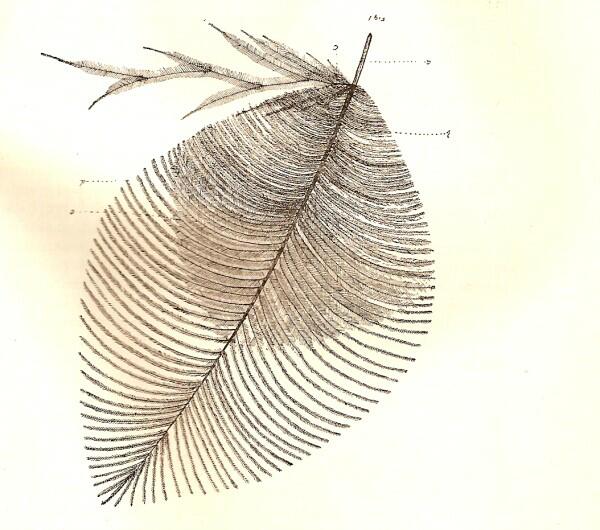

Such surveys can be quite helpful in a limited fashion, but they can also be misleading. Many biology texts present Paramecium as a typical example of a ciliated protozoan. The main reason for this is that it is ubiquitous, but just because an organism is abundant and cosmopolitan does not mean that it is typical. The “generic” models of a “typical” cell or feather are also problematic; useful if one understands the limits, misleading if one doesn’t. Nonetheless, Mr. Peck presents a very nice exposition with some fine drawings, one of which I’ll include here.

I am also including a closeup image which I took of a feather from an old feather duster. You can see all the tiny barbels extending from the shafts.

Finally, we get to the last of these early magazines with Vol. 1, No. 3, July and August 1903 of The Atlantic Slope Naturalist edited and published bi-monthly by W.E. Rotzell, M.D., of Narberth, Pennsylvania. There are three brief items I want to take a look at. The first is a letter with the heading:

A Critical Non-Supporter

Dear

Sir: Your little journal has been received and I would like to

be a subscriber but really do not approve of killing birds to

find out their names...The best way to study birds is by note

and not by shot gun. If you will make an effort to stop the

slaughter of birds you can put me down as a long

subscriber.

Very

truly,

D.

Minehan

A

devilish dilemma! From one perspective, I greatly admire the

doctrine of “reverence for life” as it develops from Spinoza

to Goethe to Albert Schweitzer. On the other hand, our

knowledge of the natural world would be much impoverished

without access to specimens. With adequate and proper

research, we can find ways to help preserve species and

protect them from radical threats of diseases, toxic

environments, parasites, and excessive predation. However,

this last must include human predation and the protection of

more of the environment from developers, many of whom are

predators of the worst sort. Humans have long sought gold,

silver, diamonds and other precious stones and metals, but

have all too often forgotten or ignored the biological

treasures of planet Earth. These are the sort of treasures

that can endure only if we understand that part of our role in

nature is to be the caretakers of

Earth.

This

little magazine also has an utterly delightful short piece

titled “Early Risers” by Thos. G. Gentry, Sc.D. and I am

sorely tempted to simply reproduce the whole thing here since

it is only 1 1/3 columns, but this essay has already gotten

quite long. However, I will give you a brief, pale summary

here. Dr. Gentry recounts how during a period of recovery from

typhoid pneumonia, he undertook a modest experiment which

raised his spirits and perhaps even aided his recuperation. He

had a clock and a lamp placed such that he could see the time

in his darkened room and he observed the time each day that he

could hear particular birds. He was a man with a rather

florid, but pleasing, style and I will quote one brief passage

to give you a sense of

it.

“The

hour of five found the summer yellowbird and the song sparrow

sufficiently awake to add their quota of

delight.

But

scarcely had they thrilled the fields and groves around with

their sweet cadences, than they were hushed by sounds more

shrill than jay or crow e’er uttered, for the sparrows–those

hateful, saucy gamins from Albion’s shores–had now essayed

their

matins.”

The final item I want to look at is an advertisement inside the front cover for a book by our good Doctor of Science, Thomas G. Gentry–yes, he of the purple prose above and this notice suggests that Dr. Gentry was a bit of a loon. His book is titled: Life and Immortality! or Soul in Plants and Animals . The purveyor, W. Aldworth Poyser, informs us that he has acquired the remaining copies of the author’s private edition (suggesting that perhaps Gentry paid to have it published) and further tells us that this “large octavo [of] 289 pages, cloth, profusely illustrated’ which previously sold for $2.50, he is now by special arrangement with the author, offering for $1.00 and furthermore that these are autographed copies. Apparently this volume didn’t make The New York Times bestseller list.

Here is

the description of the

book.

“The

intelligence of plants and animals is depicted as never

before. The work is not as one might suppose from the title–a

controversial treatise, packed with metaphysics, bristling

with thesis and theory with disputatious argument. The theme

is handled with skillful simplicity by a master

hand.”

I would love to find a copy of this “treatise”; in fact, I’d even be willing to pay the full price of $2.50 without the autograph–since it’s profusely illustrated, it would be worth it to get a glimpse of a diagram of the soul of a philodendron or petunia let alone a wildebeest or wallaby. Why not? After all the French philosopher, Jacques Maritain provided a diagram of the human soul in his book Creativity and Intuition in Art and Poetry .

Addendum

I decided to Google Gentry’s book and found used copies of it priced from $20 to $60. I also discovered that it has been reissued (2003) in a paperback which is also available for about $20. I checked the university library, but it doesn’t own a copy. So, I guess I’ll have to soldier on not knowing what the soul of a philodendron looks like as I’m not sure my curiosity extends to $20 in this case.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .