Revisiting an old illumination technique.

Improving a Jessops slide viewing panel for use with the microscope.

By Ian Walker. UK.

Fig 1. Box re-assembled with the diffuser panel removed showing the small fluorescent tube and original curved silver reflector, the tube is showing its age by the dark grey banding at the bottom end but are reasonably cheap to replace.

Fig 2. shows a new thick cardboard panel accurately cut to fit the original surround and reduces glare, the large aperture is of sufficient diameter when using low power objectives with the diffuser back in place.

Behind the aperture there is a slightly smaller ring stuck to the back this allows an accessory disk to be fitted from the front without it being accidentally pushed all the way through. Referring to Fig 2. the first improvement noticed when using medium to high power objectives over the unmodified version is light output which is about doubled in brightness but more importantly is the 'quality' of light which has more penetrating power compared to the diffuser and gives a significant improvement in contrast and fine detail especially diatom structure. The tube width is sufficiently wide to allow complete illumination over the field with a 40x objective and simply holding a narrow object at the bulb surface allows focus of the condenser.

Fig1. Fig 2.

Fig3.

Fig 4.

Fig 4. Detail of 'slot illumination' accessory panel fitted to the aperture hole with diffuser removed, to remove the panel I simply pull it out with the edge of one of my metal dark field stops. A smaller cardboard ring fitted behind the main aperture overlaps by about 1mm preventing the panel pushing through and importantly removes light escaping at the perimeter.

Lamp in action with 'slot illumination', the lamp box is placed around 9" away from the mirror of the microscope just out of view at the right and here the lamp is being powered by the low voltage mains adapter with the wire trailing off at the top of the box. By careful placement of small feet the enclosure points slightly downwards without being too excessive to cause instability.

Fig 6.

With the demise of decent external Kohler lamps many years ago and the difficulty now of getting hold of them a simple light source like this can work well and is a big improvement over the unmodified version of the Jessops light box and is certainly worth experimenting with. LED illumination can work well but I never got it to work to my total satisfaction for both low and high power objectives when I optimized it for one the other would get worse in consequence but this is most likely down to optical components available to make both work equally satisfactory.

Whilst I carried out these tests I borrowed my brother's LOMO external 15 Watt filament lamp and power supply for the LOMO Biolam microscope with the same objectives and my old microscope. I have always been rather indifferent about this lamp it seems you are forever fiddling around with clear blue filters [sometimes one, sometimes two] ground glass [sometimes with, sometimes without] and have enough range on the illumination level plus sufficient aperture for low power work but I persevered to compare results with my lamp. I was pleased to find out that my simple illuminator stands up well against this lamp without the heat, better white balance without the need of filters and a big improvement when using low power objectives using the original diffuser. Regards flare and the 40x objectives the LOMO doesn't seem any better even though it has a condensing lens and diaphragm, also filament 'colour abnormalities' can be seen even when using these objectives so I dutifully gave him it back and went back to mine. Even though it uses a fluorescent bulb most digital cameras can cope with this either by using a dedicated setting on the white balance menu or auto mode works well on my Sony.

Fig 7.

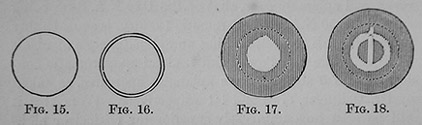

'The last point before the appearance of the black spots furnishes the position in which the condenser has the largest aperture consistent with its outstanding spherical aberration not too much interfering with the highest results, and is the limit of the condenser for critical work. Any further advance of the condenser gives merely annular illumination, which, of course, is to be avoided, excepting when stops are used.'

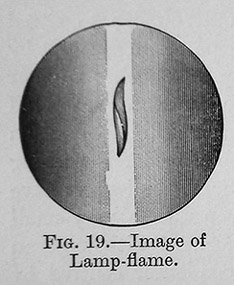

And on using the edge of the flame for illumination, an extract taken from 'The Microscope - A Practical Handbook' by A. H. Drew D.Sc. F.R.M.S. and Lewis Wright 1927 [who also details the use of the edge of flame to determine the aplanatic cone of the condenser shown in Fig 17. and Fig 18]:

'The partially illuminated field often seems strange to the beginner, but he should bear in mind that our object is to secure the finest definition and illumination in the centre of the field and the rest is neglected.'

I have found this method quite useful sometimes in obtaining a little more aperture from the Abbe condenser compared to its usual position but only a small deviation is required to obtain a brighter image consistent with a slight improvement in definition of fine detail excepting the edge of the focused slot is more diffused compared to Fig 6. above.

Fig 8.

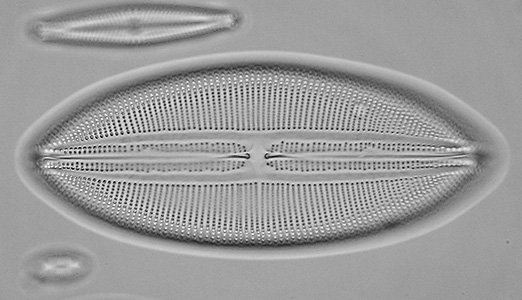

Navicula henndyi.

Fig 9.

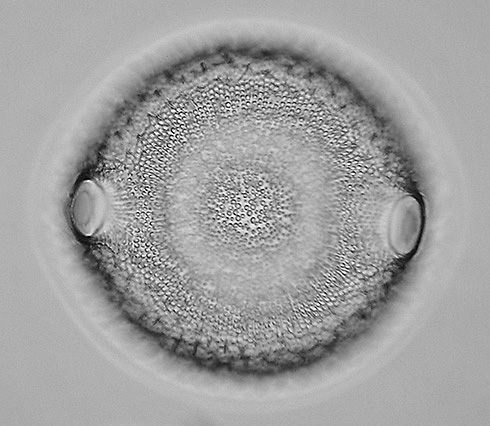

Biddulphia edwardsii.

This little fellow could do with image stacking but shows good definition in the focus plane.

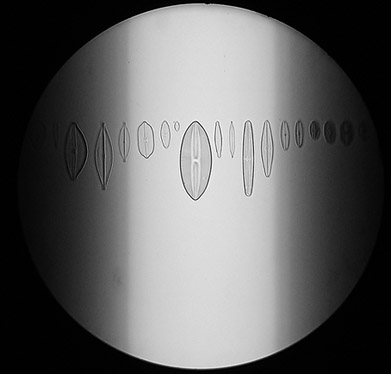

Fig 10.

Group diatoms.

Very old John Browning 1/4" objective the illuminating section can be narrowed by movement of the lamp, compare this to Fig 6.

Conclusion.

Reference: Jessops 5"x4" [lit area] slide viewing panel can still be obtained from their website [www.jessops.com] for £14.99 inc VAT at the time of writing this article with spare daylight corrected tubes for £6.50 they also sell the matching 240V ac mains adapter which also has various preset output voltage settings making it quite versatile, I also noticed a more expensive slimmer version of light panel with 'new technology' [whatever that means, but possibly using LED's which could be interesting].

Note: Their search engine is poor and at first I thought they had stopped selling them but the search engine doesn't find their own product, its under the main heading of accessories > enthusiast products > projection/viewer > light boxes.

Comments to the

author,

Ian

Walker,

are welcomed.