|

|

A Close-up View of the Wildflower "Lesser Burdock" (Arctium minus) by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

|

|

A Close-up View of the Wildflower "Lesser Burdock" (Arctium minus) by Brian Johnston (Canada) |

A Burdock-clawed my Gown-

Not Burdock's-blame-

But mine-

Who went too near

The Burdock's Den-

Emily Dickinson

Lesser burdock is an extremely common weed in North America. The examples photographed in this article were found growing along an abandoned railway line and at the untended edge of a golf course. The name derives from the French word "bourre", which is from the Latin "burra" meaning a lock of wool, and the English "dock" referring to large leaves. (The lock of wool reference may be due to the fact that sheep often get burdock burrs caught in their coat.)

The image below shows the top of a typical plant with three flower heads in different stages of development. On the right is an immature head which consists only of hooked bracts. The left head is just beginning to bloom, while the central head is in full bloom. The leaves are spade-shaped or oval and are connected to the main stalk by short stems. The undersides tend to be whitish green and slightly woolly.

As can be seen in the following two images, the surface of the leaf is very three-dimensional.

The immature flower head is covered by many layers of thin green bracts tipped by pinkish-red hooks. Notice that the open side of the hooks face the centre of the flower head.

A higher magnification reveals the details of a hook. The base is green, the neck red, and the tip yellow. Insects often utilize these hooks as supports for their web construction. The Swiss inventor, George de Mestral studied the efficient clinging tendencies of burdock hooks in order to develop his brilliant and useful invention, the fastener VelcroTM.

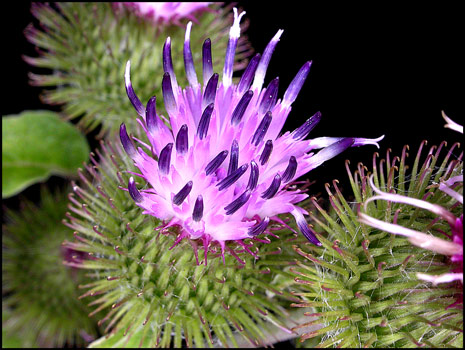

As the flower head begins to bloom, the topmost hooked bracts are pushed aside to reveal a vertical cluster of individual flowers with fused pink petals. The burdock is a member of the Aster family, and as such, displays composite flower heads. Each pink column in the head below is an individual disk-type flower. (There are no ray flowers in this species.) Projecting out of each flower is a deep purple column of fused stamens (the male, pollen producing organ). Flower heads are usually two to three centimetres in diameter.

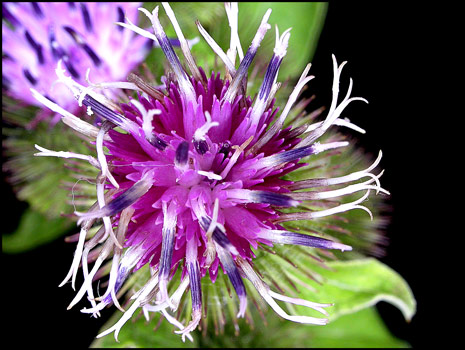

The flower head below is at a later stage of development, and the column of fused anthers has grown longer in each flower. Several flowers at the outer edge show the bi-lobed stigma, (the female, pollen accepting organ), that projects from the centre of the column of anthers.

At a higher magnification, the five fused pink petals with white bases can clearly be seen in each flower. Notice how the bract hooks have been splayed out away from the central column of flowers.

As the bloom matures, more flowers display the white bi-lobed stigma. Notice the white woolly texture of the bottom of the leaf on the right.

Eventually, these white stigmas grow so long that they may begin to tip over due to gravity. The great difference in appearance between mature (right) and immature (left) flower heads is striking.

Two views of a mature flower head can be seen below.

An extreme close-up of a flower head shows several flowers in various stages of development.

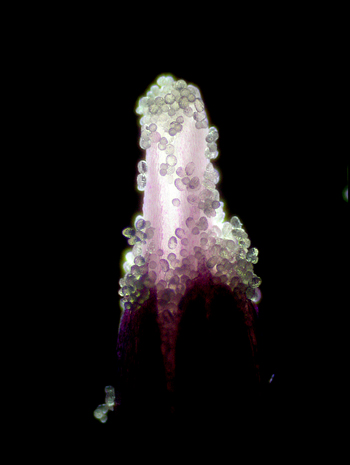

The photomicrograph below, taken using dark-ground illumination, shows the midsection of a single flower. At the bottom, the purple fused petals form a ring around the five purple anthers, each with a distinctive spike-shaped tip.

At an earlier stage, the light pink pistil (which will eventually show a definite stigma and style) has begun to protrude from between the anthers. This entire section of the flower is coated in pollen grains.

A higher magnification reveals the ellipsoidal, rough surfaced pollen grains more clearly.

As the pistil is forced farther out of the anther-formed tube, the two lobes become visible. This is the mature stigma. (Note that for the purpose of photographing it on the microscope slide, the stigma has been removed from the flower.)

The branching point of the stigma above is shown below, at a higher magnification.

When the blooming cycle has completed, the flower heads dry out to form the most recognizable part of lesser burdock - the burr. Since the connection of burr to stem is relatively weak, the burr hooks can become attached to clothing or animal fur when they are brushed against. Each dried flower head contains many seeds and may be carried great distances by this transportation technique.

During the Middle Ages, burdock was believed to be very valuable in the treatment of diseases and common ailments. Today burdock is often referred to as a coarse, unsightly weed. However, from a macroscopic or microscopic viewpoint, I think that it has many unique and interesting characteristics.

Photographic Equipment

The images were taken using a Sony CyberShot DSC-F717 equipped with a combination of achromatic close-up lenses (Nikon 5T, 6T and shorter focal length achromat) which screw into the 58 mm filter threads of the camera lens. (These produce a magnification of from 0.5X to 9X for a 4x6 inch image.) Still higher magnifications were obtained by using a macro coupler (which has two male threads) to attach a reversed 50 mm focal length f 1.4 Olympus SLR lens to the F 717. (The magnification here is about 13X for a 4x6 inch image.) The photomicrographs were taken with a Leitz SM-Pol microscope (using a dark ground condenser), and the Coolpix 4500.

All comments to the author Brian Johnston are welcomed.

Published in the August 2004 edition of

Micscape.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the

Micscape

Editor.

Micscape is the on-line

monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at

Microscopy-UK

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk with full mirror at www.microscopy-uk.net.