|

|

| WALTER DIONI DURANGO (Dgo.) MEXICO |

|

|

| WALTER DIONI DURANGO (Dgo.) MEXICO |

|

|

When liquid or jelly mountants are used, to make a permanent, or at least a very durable preparation, nail polish is often recommended as a sealer for cover glasses. Its usefulness for this task depends on its special chemistry.

Don't worry. I won't of course discuss the ingredients of the many formulas that the "industry of beauty" has devised for the almost infinite variety of products that they sell.

My concern instead is with the characteristics that the good ones must have to give the nails of women their special appearance. It must be clear and transparent, easy to apply, rapid to dry, capable of developing a hard surface, not easy to peel apart from the surface to which it is adherent. (Yes, it must also develop a high luster, and in many cases must have a beautiful color, but really these qualities don't bother me.)

Of course, it's because of these properties that we use nail polish as a sealer; clear polish most of the time, or colored, for special applications. Additionally, when it dries, it is impermeable to water, and protects glycerin-jelly, for example, from desiccation and contraction, or inversely keeps water out of hygroscopic media like glycerin. It clings to glass and you can even use immersion oil without risking the displacement of the cover ruining the preparation.

This achievement the chemists accomplish by mixing plastic polymers, natural resins, many different solvents, plasticizers, and the like. The formulas are complex and intended to withstand long periods of storage in their glass containers, and the better manufacturers avoid unwanted thickening by designing hermetically sealed caps. Not crystallizing either or losing its transparency over time, are normal qualities of good products, even when the density increases due to some solvent evaporation.

All these features seem familiar to me. Aren't these the characteristics that we search for when we select a good resinous mountant?

Balsam, Permount, Euparal, Damar, PVA, and the like, remain liquid in their glass containers, flow easily when applied under a cover glass, dry along the borders of the cover by solvent evaporation and this prevents resin under the cover slip totally losing fluidity. The resins remain clear and do not crystallize under the glass.

All the above mentioned products, with the exception of some formulations of PVA mountants, are not miscible water. They turn milky when we try to mount an object with some remaining water, even if so little as 4%, as is the case with 96% ethyl alcohol. So, to use them, a thorough dehydration is needed, involving the use of several water-alcohol mixtures, and absolute alcohol, followed by clearing with some solvents and essential oils, and/or a final bath of xylene, before mounting.

Most of the products involved are expensive, or difficult to obtain in the small quantities an amateur needs, and some others are dangerous. And to ensure complete dehydration implies most of the time 5 or even 7 additional working steps to finish a resin mount preparation.

Thus I asked

myself whether the converging characteristics of nail polish and resinous

mountants qualified the former for the job.

|

|

|

Initially of course, I thought that to perform the experiments I would need some intermediate solvents and possibly a good dehydration. I was prepared to do that. But to my surprise objects from 96% alcohol mounted easily in the nail polish I used.

The nail polish directly receives the materials from the alcohol, maintains its fluidity for enough time to allow a careful arrangement of the objects, even to dissect some parts, and allows the cover to be put on without trapping air bubbles.

I use of course

the double drop method: Put one drop on the slide. Add the object but avoiding

air bubbles. Put another drop on a coverslip and invert it so the drop

is hanging. Now the drops are carefully put in contact. If the cover is

maintained parallel to the slide the mountant spreads evenly without trapping

air bubbles. The nail polish dries along the coverslip edges in one or

two hours, but remains fluid but viscous under the glass. If the subject

is thin and flat you can apply a certain pressure with an appropriate weight

(about 25 g is appropriate) to realize a very thin mountant layer, and

you can speed drying by putting the slides on a warm plate, in a laboratory

oven, or simply next to a desk lamp. In the last case be aware of the possibility

of excessive evaporation, and complete the mount by applying nail polish

in the voids that can appear along the borders.

|

Until now I have used the polish as it is. But I think that for certain applications, like mounting thick parts of arthropods, it could be thickened by opening the container to evaporate a portion of the solvent. Of course it would be more difficult to use it.

Any material that does not dissolve in the solvents of the mountant, can be mounted. I think it is very useful for chitinous materials, like micro arthropods, wings from diptera, other parts from insects, and some micro crustaceans, and for many other animal and plant materials. It is my favorite for mounting scales of small fish, scales from the wings of butterfly, mammal hairs and the like.

|

|

|

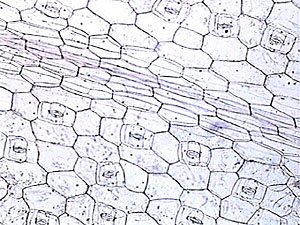

I tried with

less success two vegetable subjects. I peeled off a small square of Tradescantia

leaf epidermis, fixed it in a bath of 5% formalin for 1 hour, washed it

for 30 seconds in a water bath, and transferred to 96% alcohol for one

minute. When I mounted these materials in glycerin the result was a very

good preparation, and if you seal the borders it lasts a long time. When

I tried the NPM (Nail Polish Mountant) the immediate result was also fairly

good. But deteriorated after one or two additional days, the epidermis

became excessively transparent and showed a most unnatural appearance.

|

|

|

|

I have also mounted in glycerin by the same method some branches of the alga Cladophora with the same good results and the color of chlorophyll was conserved for months. Mounted in NPM the color fades, and the cylindrical branches collapse and became flat clear strips that appeared to be only the ghost of the live alga. |

Don't blame the NPM for the bad results. It is really difficult to mount those materials in any resinous mountant. Canada Balsam gives similar results.

|

But the mounting of other normal biological subjects needs more experimentation to see if they can be mounted in NPM in reasonably good condition. At least similar to the results obtained with Canada Balsam, Damar Balsam, and the like.

Dry objects or those with a minimum of water could be mounted directly. Other subjects such as minute larvae of insects must be dehydrated using one bath of 50% alcohol (in a graduated cylinder put 50 ml of 96% alcohol, and pour in water up to the 96 ml graduation) and another of 96% alcohol, both 5 to 10 to 20 minutes each. To avoid air bubbles I think it is better to give everything an alcohol bath before mounting it.

The use of alcohol is also needed, because what turns the new mountant milky is grease. The alcohol dissolves it out of the bulb of hairs for example. You must judge each situation. Indeed I think you could be pushed to use a more powerful degreaser. Ladies always have, next to the nail polish, a bottle of acetone, butyl alcohol (banana essence) or some trade mark solvent to wash it away. Feel free to experiment. Give the subjects a bath of solvent after the alcohol bath and before mounting. If you are not the husband it's possibly not your money.

As we gain experience with this new mountant, I think that we need to try more delicate methods to also mount delicate materials. The dehydration series used for balsam mounting can be a guide. Our solvents must be ethyl alcohol (ethanol) and acetone. Acetone (easily obtained over the counter in drugstores) mixes in all proportions with alcohol and with the NPM. So we could pass from water to alcohol and from alcohol to acetone and to NPM in a gradual way.

Don't worry if, when you think you have finished your slide and go in a hurry to the microscope, you see tiny (or not so tiny) pools of alcohol under, over, or around your subjects. Put it aside in a nonchalant manner, and continue with your days work. Next morning an almost perfect slide could be waiting for you. Sometimes the slide improves after one or two additional days.

One useful intermediate liquid is glycerin. You can put dry materials in glycerin, subjects coming from water, or from alcohol. If the subjects are soft and delicate, you could possibly use an intermediate step. Put the materials in a bath of enough 20% glycerin in water, and leave to evaporate for two or three hours. Take the object from the concentrated glycerin, but minimising any glycerin carry over, put it in the nail polish, and mount by the double drop method.

Other materials that are alive when you collect them, must be fixed, and variously treated before mounting them. But this needs that you read carefully other articles in the Micscape Library, in the books in your own library, or that you wait a further contribution from myself.

Specimens mounted with NPM are especially suitable for study with oblique illumination.

Time and experience will show us if the new mountant could preserve histological stains for any length of time. The NPM I use contains citric acid, and acids fade dye colors like haematoxylin. It remains to be seen if there is any one nail polish formula that is neutral or slightly alkaline.

Anyway I have carried out some experiments and am waiting for some months to pass to assess the results.

For the time being, thanks to the special chemistry of nail polish, it is a safe and easy to use mountant, cheap (especially if you borrow it from the ladies in the family), really easy to find and to buy, with very good optical qualities, that allows many interesting things to be prepared for microscopical observation, and photomicrography.

In summary, NPM is a very easy to acquire "resinous" mountant which deserves to be added to glycerin, karo, fructose, and glycerin-jelly, i.e. the "aqueous" mountants now used by many amateur (and professional) microscopists. Gum Damar, that is also easy to get and not expensive, is a resinous material that needs dissolution in xylene, toluene or benzene; all three are toxic solvents that the amateur (and the professional) must be wary of.

All comments to the author, Walter

Dioni, are welcomed.

Please report any Web problems

or offer general comments to the

Micscape

Editor,

via the contact on current

Micscape Index.

Micscape is the on-line monthly

magazine of the Microscopy UK web

site at Microscopy-UK