Humans have a near-infinite capacity for tolerance, even if it's not exercised very often. One thing is sure, we share a mutual bonding when experiencing something that is truly intolerable. The time is now upon us to seek shelter, wrap heads and wrists and ankles, try every kind of evil-smelling concoction, and employ a vocabulary best laid aside in company. It is blackfly season, the time of itching bites behind our ears, under watchbands and socks. Picnics are ruined and so are dispositions. We retreat to appreciate wildflowers, birds, and butterflies from behind closed windows and ineffectual screens. I even wear a bee-keeper's netted hat when spending long hours out of doors.

How can a biologist admit to a dual viewpoint of blackflies? To run from their hungry attacks, swatting away, yet to lie in quiet fascination upon a brookside rock, watching tiny creatures go about their business? It's all a matter of the insect's stage of life and degree or maturity, whether it is a youth or a grown-up—also whether it is a male or female. As a nostalgic septuagenarian, it may be natural for me to side with youth. But as a wary male, I dare make no comment about gender. All I can say about the adult female blackfly is that she is an efficient blood-sucker possessing a chemically sophisticated saliva that keeps my blood from clotting while she drinks her fill. It is this same saliva that arouses our own body chemistry to react with an extremely irksome inflammation. Having a highly-developed sense of survival, a female blackfly bites us precisely where we are least likely to notice her presence. After she has drunk her fill, she flies off to rest and digest her meal in an obscenely inflated body that is blood-red when seen by transmitted light. She is an elusive little Dracula. The males? Well, they are inoffensive creatures who sip only nectar from flowers. That's no surprise: males the world over are generally nice. (My wife has not proof-read this.)

It is the larval blackfly that is worthy of tolerant attention. Anyone who has looked closely at a brook will have noticed juvenile blackflies, but probably not known what they are looking at. Go to a riffle where the water flows rapidly over a flat rock before it plunges into a pool. On the brink of the rock, where water is swiftest, you'll find dozens of small black twiglike objects, bent downstream by the force of the current. Each is about a quarter of an inch long. As far as their appearance goes, they could be anything—plants perhaps. Now look more closely.

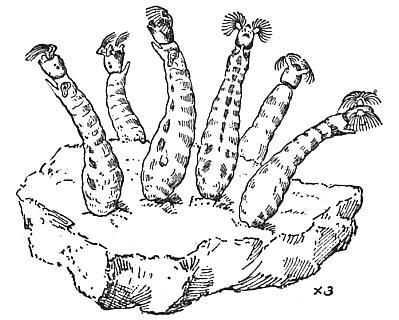

'Group of larvae of Simulium attached to a stone.' Figure 59 from 'Miall' (see picture credits). |

You will see an elongated, brownish insect larva, somewhat club-shaped with the bulbous end attached to the rock. At the narrower upper end is a small dark head from which two fringed appendages extend outward. You can't see the details, but hooks on the bottom of the larva hold it in place on a mat of silk that is firmly attached to the rock's surface. By weaving this silken mat, the insect establishes home base.

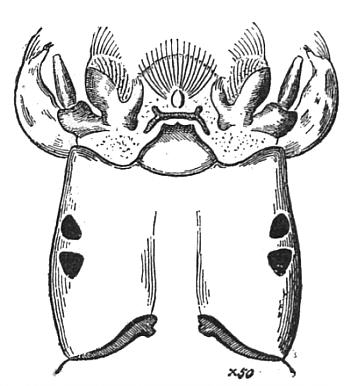

'Head of larva of Simulium, ventral view, showing mouth-organs. The eye-spots of the dorsal surface are seen through. Figure 61 from 'Miall'. |

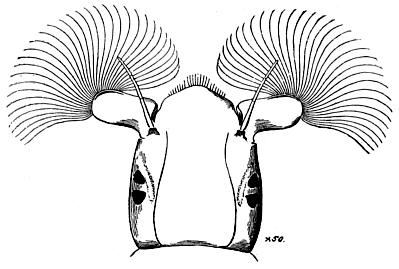

'Head of larva of Simulium, dorsal view, showing eye-spots, antennae, and fringed appendages.' Figure 60 from 'Miall'. |

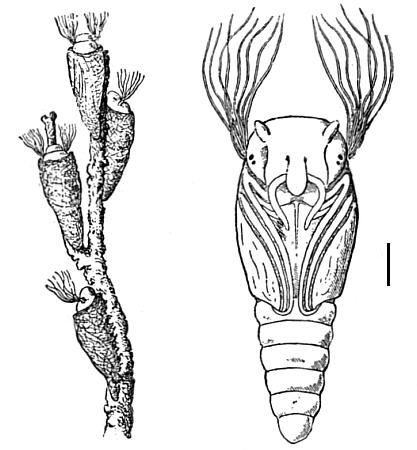

The life stages of a blackfly are like those of any other fly—or beetle or butterfly or moth: egg, larva, pupa, adult. A female blackfly may actually enter the water to lay up to 500 eggs, or choose a wet leaf along the stream bank on which to deposit them. By means of a pointed "egg burster" on its head, each tiny larva hatches, creeps carefully through the swift water to find a place of attachment where it feeds, molts up to nine times as it grows, then enters a non-feeding stage while it transforms into a flying insect. For the blackfly, this is accomplished underwater in a hump-backed little pupa securely inside a spun cocoon. Two sets of feathery gills extend from the pupa and trail downstream to extract oxygen from the water during this critical transformation.

Left: 'Four pupae of Simulium in their cocoons, attached to aquatic stem.' Right: 'Pupa of Simulium, removed from its cocoon.' Figure 65 from 'Miall'. |

Sing praises to this scourge of the north country, this highly-evolved little inhabitant of our upland brooks. If for no reason other than to witness an extraordinary specialty in a turbulent watery world, the blackfly is worth knowing about. And even if I swat a dozen (females), I'll still lie by my brook and marvel at these wondrous little creatures.

Comments to the author Bill Amos are welcomed.

© 2000 William H. Amos

Bill Amos, a retired biologist and regular contributor to Micscape, is an active microscopist, naturalist and author. He lives in northern Vermont's forested hill country colloquially known as the Northeast Kingdom.

Editor's notes: Other articles by Bill Amos are in the Micscape library (link below). Use the Library search button with the author's surname as a keyword to locate them.

Picture credits: Images

and captions are from the 1912 reprint of Professor L. C. Miall's book

'The Natural History of Aquatic Insects', Macmillan and Co., London, first

published 1895. The illustrations in this book are credited to A. R. Hammond.

Image scans by David Walker (Micscape Editor).