Recently I was going through some old image files and came across a collection of intriguing objects, all of them fossils and all of them older than me. These particular fossils came from samples which a generous colleague in the Geology department passed on to me. He was retiring and learned that his position in micro–paleontology was not going to be continued. Concerned that this material might simply be discarded, he passed it on to me knowing of my interest in things, micro, mini, and macro.

I will give you just a few examples from a collection of many thousands. As you might expect, there is a dominance of forams (or foraminifera, if you want to get picky); however, there are some really quite intriguing surprises as well. I am by no means a formaminiferologist nor even a fossilologist, but I’ll do my best. Let’s start with 2 examples that are rather “classical” forms with regard to forams and are quite lovely.

I quite like the texture surface of this specimen and one can get a good sense of the internal spiral morphology.

The suggestion of the spiral form is also evident here and this has a different, but nonetheless, pleasing surface texture. There are many other forms with radically different morphology. Next, I want to show you a couple of “palmate” forms. The first example is somewhat coarse in appearance, but a flattened, elongated spiral form is nonetheless discernible.

The next example is much more elegant and even has a “handle” so you can use it as a fan.

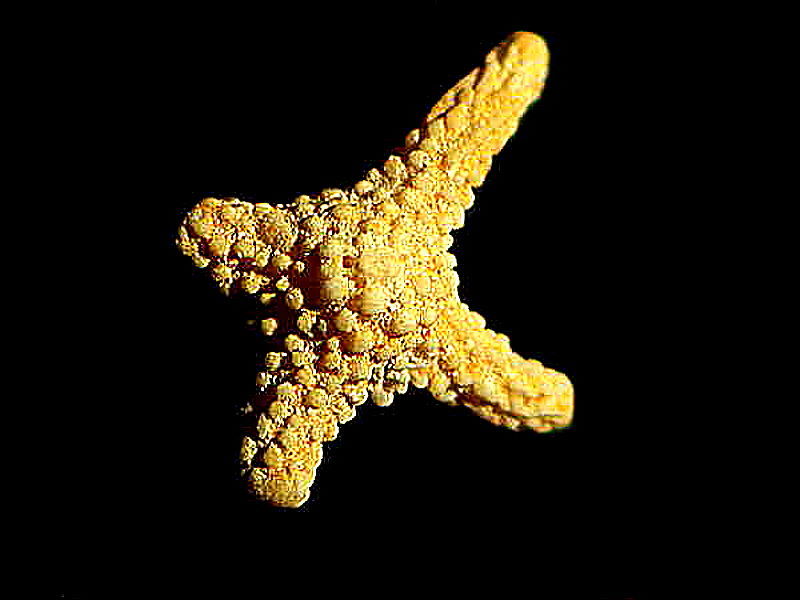

The world of forams is full of oddball forms, so let’s explore some of the unusual ones. The next two examples are roughly stellate and are tropical.

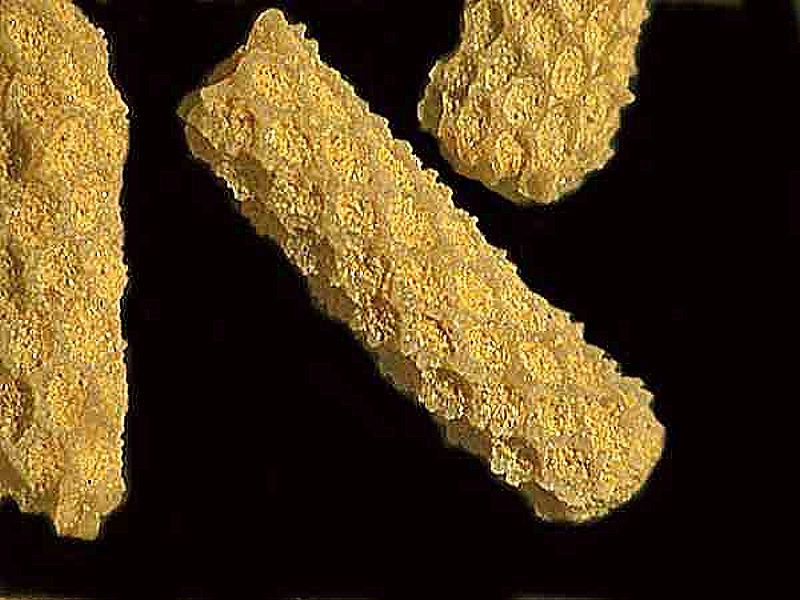

Now imagine a tiny elongated seed pod and this somewhat describes what a fusulinid foraminiferan looks like.

Now, if you are wondering, can a tiny blob of protoplasm, an amoeba, construct such a thing with an elaborate internal matrix of chambers; the answer is yes. Well, if we split one open to get an inside view, here is the result

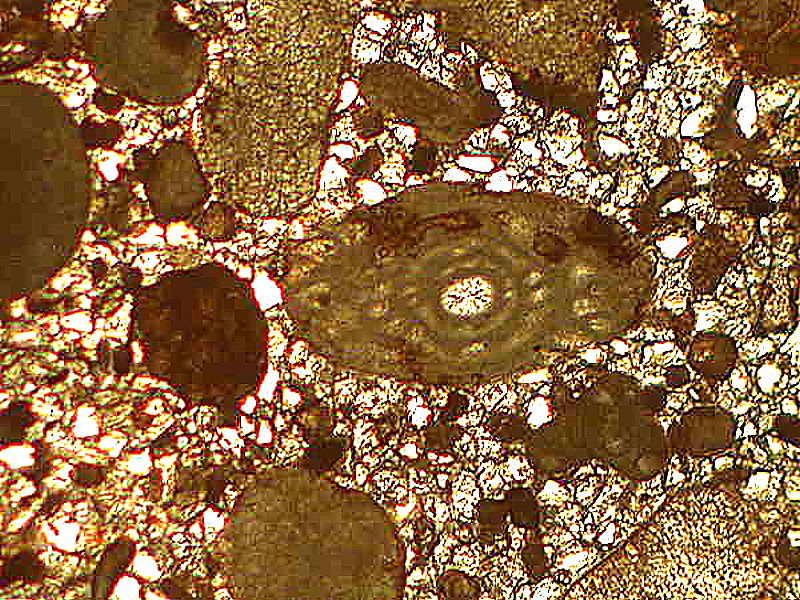

Again, there is the hint of spiral arrangement, but much depends on the cross section and to a certain extent the genus. The fusulinid genus Pseudoschwagerina can provide us with splendid examples. First, I’ll show you a section in matrix.

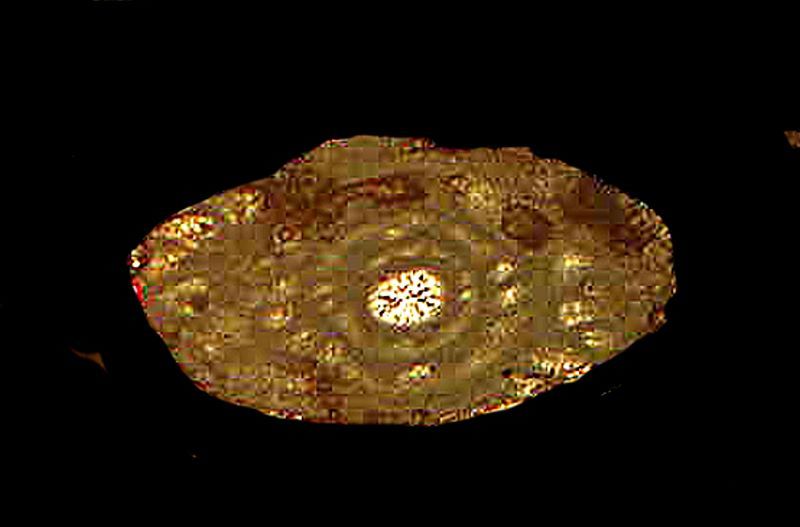

Next is the section isolated and slightly enlarged through computer magic.

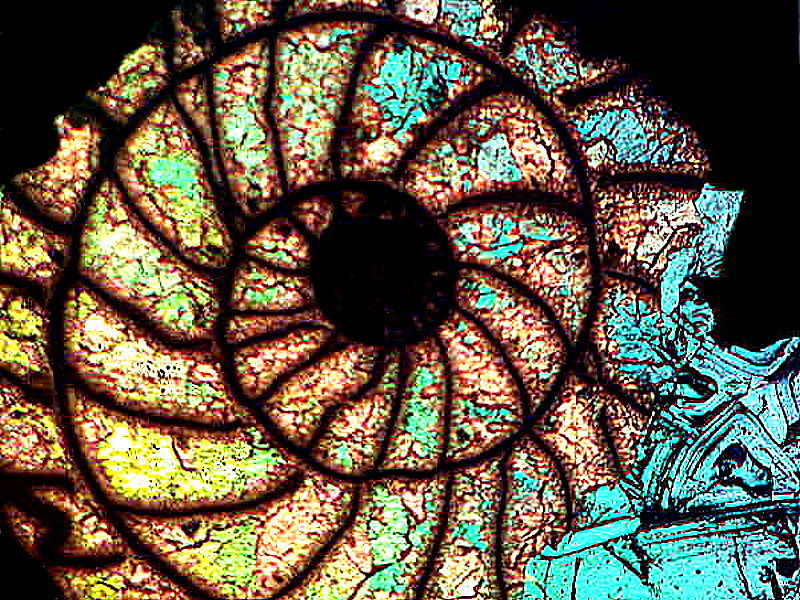

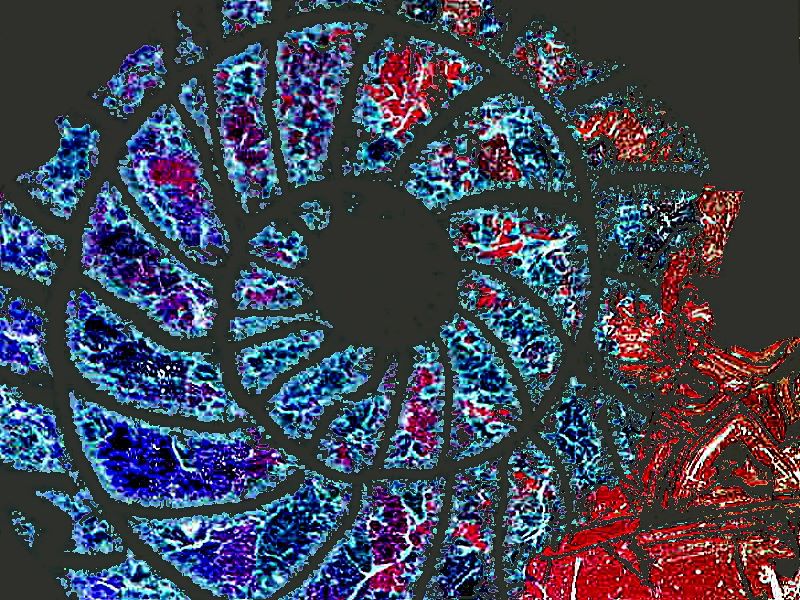

However, there are species which properly sectioned are quite spectacular. First, let’s look at a brightfield image of such a section.

A clear and striking example of the Fibonacci spiral.

However, using that brilliant technique of Nomarski Differential Interference Contrast (DIC), we can produce a “stained glass” spiral which, given the necessary accomplished artisans, technicians and benefactors, some cathedrals would love to have in their windows.

But, if you would like something more modern for your temple, using computer magic, we can, using the inverse graphics function, produce the following–rather exciting without being too distracting.

A beautiful, glass organism that “flies” through the water is the “sea butterfly” or pteropod, literally “wing-foot”. Naturally, taxonomists are quarreling as to where these extraordinary creatures “fit”. Traditionally, they have been regarded as mollusks or closely related thereto. However, with many of them, you look at them and say: “But, the emperor has no shell.” In most species, the shells are vestigial and rather small.

Here are a couple of elongated conical forms.

Odd little bits appear which at first glance don’t seem to be much at all, like this little white lump, which after closer examination of the surface and shape, I realized was the textured shell of an ostracod.

Ostracods have many extraordinary characteristics, but knowing your salacious natures, I”ll give you a remarkable fact about their “naughty bits”. I quote from Wikipedia (and, yes, you should donate to them–some good stuff there).

“Male ostracods have two penii, corresponding to two genital openings (gonophores) on the female. The individual sperm are often long and are coiled up within the testis prior to the mating; in some cases the uncoiled sperm can be up to six times the length of the male ostracod itself.”

This information must be kept secret among the fellowship of microscopists; imagine what a terrible blow this would be to the ego of the average human male!

Bryozoan (moss animal) fossils are also quite common micro-fossils. Some living forms are often mistaken for hydroids, but they generally don’t preserve well. The usual fossil forms have a robust, calcareous exoskeleton. I’ll show you 3 examples here. Each of the indentations is a place where a tiny zooid lived.

On the upper right in this last image, note the small spiral. This is not part of the bryozoan colony, but rather the remainder of a calcareous tube from a tube worm which had attached itself to the bryozoan. The tube worm was probably a relative of the genus Spirorbis and the protruding part of the tube has broken off showing how it was attached.

Next let’s look at a reproductive structure from a freshwater alga known as Chara (also known as a stonewort) which grow in hard water and are covered with calcareous deposits.

While this is a fossil specimen, I have collected Chara in ponds here and found precisely the same structures.

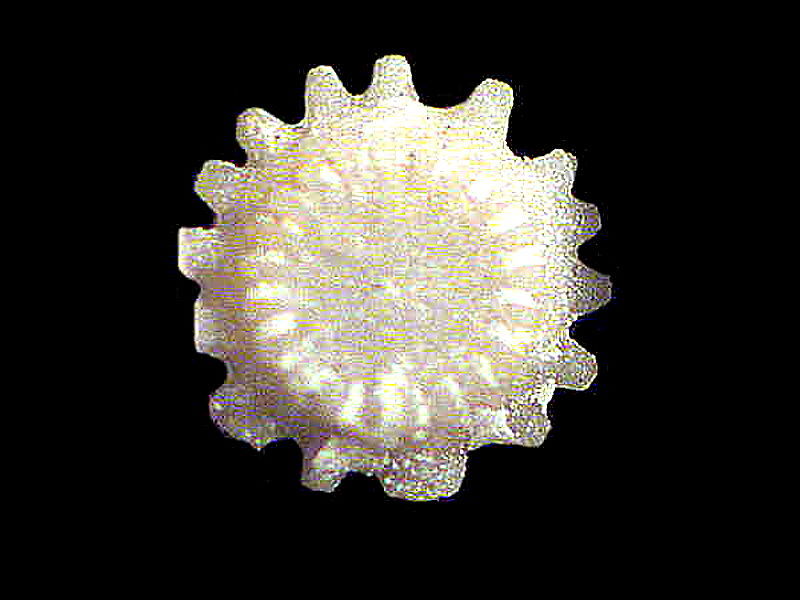

Now I would like to show you something that has a very pleasing symmetry. At one time, ancient seas were populated with enormous numbers of crinoids or “sea lilies” which are echinoderms and some of them had stems that exceeded 60 feet in length, although most were only about 1 to 3 feet. The stem is composed of stacks of ossicles or plates with tissue running through them binding them together. In some fossil beds enormous numbers of the plates are found. There are a number of different types of ossicles depending on the species, but this one I find particularly to my liking.

Finally, I will present you with some examples of micro-fossils that generated heated debate for decades. This was because since their discovery in 1856 by Pander, all that was known of them were the teeth and only, in the last 30 years or so, were 11 fossil imprints showing some of the soft tissue discovered. These showed animals ranging in size from 1 cm/ to 40 cm. The conodont is now thought to have been a small eel-like animal with ray shaped fins and a notochord. It is thus classified as a vertebrate of a very early and primitive type. However, for over 150 years, all that was known of it was the teeth of which I shall show you 5 examples.

This one looks like it would be very unpleasant to be impaled upon.

Perhaps for some hirsute micro-beastie, this might have made an acceptable comb.

So, the point of all this is, that if you get the chance to explore micro-fossils, by all means seize the opportunity. However, if you encounter some galumphing macro-fossil such as myself, then flee.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Editor's note: Visit Richard Howey's new website at http://rhowey.googlepages.com/home where he plans to share aspects of his wide interests.

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

© Microscopy UK or their contributors.

Published in the April 2020 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

©

Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995

onwards. All rights reserved.

Main site is at

www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .