I was thrilled to hold a shell thought to be a million years old or perhaps much older. It is a bigger thrill, full of expectations, to posses a fossil shell that is matrix filled. I wondered what, if any, microscopic treasures were hidden within? From a friendly fossil collector in Florida I was able to acquire five matrix filled shells, the largest being 6 inches in length, approximately 15cm, and the smallest barley two inches, 5cm, from the Pliocene epoch, 5.3 to 1.8 mya. The Pliocene was a time of cooling after the warmer Miocene, cooler but still warmer than today's climate. Sea level of the Pliocene is thought to have been 30 meters higher then it is today. These shells were dug from a pit in Desoto County Florida, located more then twenty miles from the coast in an area now covered by citrus groves and pastures. Desoto County is well known for its marine fossils that span the Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene epochs.

Removing matrix from one of five shells.

After removing the matrix from the shells I had a pile of rubble consisting of small shells, broken bits of shells, lots of broken bits, and sand. To separate the macro material from the micro I manufactured an ad hoc sieve. This sieve was made using two plastic cups with their bottoms removed, a piece of nylon stretched across the bottom of one cup and then inserted into the other to hold the nylon in place. With this sieve I would defiantly flunk an introductory geology course but it worked well for the intended purpose. Now there are two piles of material, one with large pieces looking like a pile of shells and rubble and a second looking much like beach sand. I began my search with the larger material. I first removed the large shells some in good shape, most worn or broken, several with a single small circular hole drilled through the shell. I then searched the remaining material using a binocular microscope.

Macro photo of preditor Natica at top and prey

The binocular microscope revealed more shells some again with the single hole. The shells large and small with the drill hole were all bivalves. None of the gastropod shells exhibited any holes. I later learned that these holes were the result of predation by gastropods upon the bivalves. Carnivorous gastropods like Natica, informal name Moon shell, will drill a bevel-edged hole in other mollusks and suck out the contents. Other discoveries were fossilized fish teeth and coal black fossilized bits of teeth and bone. The real thrill was the discovery of foraminifera tests, not many, about two dozen in each of the first two shells examined, but very exciting.

Micro shells and foraminifera tests

Turning to the sand like material with the compound microscope I had great expectations of finding diatoms. I have come to believe, where there is water or where there was water, there is to be found diatoms or diatom frustules. Well, my theory about the presence of diatoms requires some modification. After several hours and many samples not a diatom was found. Instead I was delighted to find micro sized shells, sponge spicules a plenty, forams, and the exciting unknown. Careful searching first at medium power and then at high power was required but the effort was amply rewarded.

One of many microscopic foraminifera.

Foraminifera, Textularia type.

Triaxon Sponge Spicule.

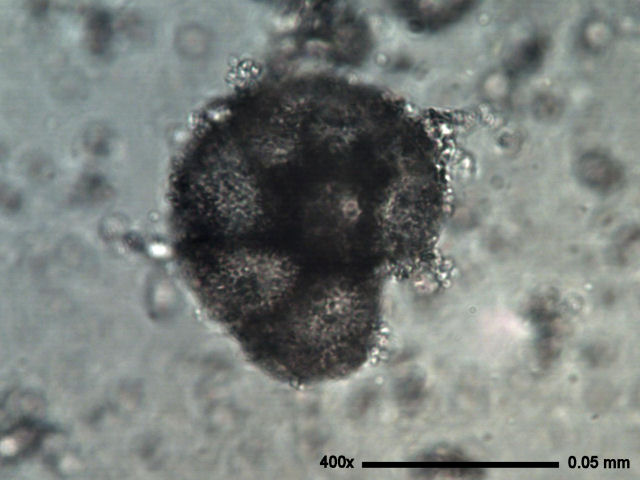

Unknown 1.

Unknown 1, pictured above, was a very exciting and puzzling find. The narrow depth of field of this picture hides four additional bullet shaped spines jutting out toward the viewer at an angle of approximately 30 degrees and I suspect that there are others on the reverse side. What could this defensive object be or be a part of? Did I find and observe a complete form or were additional spines missing? Finding and observing is great fun but attempting to identifying these microfossils is a real challenge for this novice.

Unknown 2.

Unknown 2 was also an exciting find. Again the limited depth of field of this image dose not show all the bullet shaped projections. This object strongly resembled a Christmas tree ornament of a multi faceted star. This may be a small part, possibly a siliceous spicule, of a larger host. The tired old saying, 'one man's junk is another mans treasure', can be very true. The five shells sent to me were of no value to a fossil or shell collector. The fossil hound I acquired these from was happy to part with them and I in turn was happy to accept them. These common poor quality shells turned out to be a treasure chest of microscopic gems.

The author welcomes comments or suggestions.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK web site at Microscopy-UK.