|

Resinous History: Insects in Amber by Richard L. Howey, Wyoming, USA |

Since the appearance of the film Jurassic Park, almost everyone knows about the farfetched possibility of extracting dinosaur DNA from mosquitoes preserved in amber. Amber is the fossilized resin of certain conifers. The resin is extremely sticky stuff, has a wonderfully pungent pine odor, and if you are in a coniferous forest, it won’t take you long to collect hardened lumps of the resin. Some people like to chew it–definitely an acquired taste. If you’re lucky, you may happen across an unlucky insect struggling to free itself from this trap of natural super glue and get to observe a re-enactment of this ancient process. Every microscopist is familiar with the resin from the Canadian Balsam tree, since that resin has been used as a mountant for specimens on slides for a couple of centuries. These resins are exceptionally durable as is evidenced by the fact that in their fossilized forms, they may contain insects, plant parts, pollen; in fact, anything that is airborne and might get trapped in the resinous secretions. Pieces of amber containing insects and plant parts allow us glimpses into the distant past, in fact, millions and millions of years into the past.

It is extraordinary to think that we can get a look at creatures that existed when human beings were still just a gleam in nature’s eye. Wonderful pieces of amber have been found along the Baltic coast, in Russia, in the Dominican Republic, and in South America. And the good news is that you can buy polished pieces containing insects or plant parts for modest prices. The prices will, of course, depend upon the quality of the material, but a nice sample containing 1, 2, or 3 insects can be purchased for between $5 and $25. I bought a 4 inch polished cylinder for $40 which contains between 30 and 40 insects.

Amber can vary considerably in terms of color, size, and types of inclusions. If you don’t have the means to cut and polish pieces, you may find yourself in the frustrating situation of having 3 or 4 insects in a piece with only one of them close enough to the polished surface to observe clearly. I have a couple of such pieces and one of these days, I plan to get out my hand jeweler’s saw and some diamond files with very fine grit and try my hand at increasing the observability of a couple of insects. In my estimation--founded solely on ignorance, since I haven’t tried it yet–I think that the best results will probably be obtained by doing this all by hand. Small motorized tools can be hard to control and can lead to the damage of specimens.

Inclusions can include dirt, bits of bark, and unidentifiable debris, but even with good pieces the most common and disruptive problem is air bubbles trapped in the resin. Anyone who has made slides, using Canada Balsam as a mountant, is well acquainted with this difficulty and with amber, the techniques that one might employ to eliminate such bubbles on slides, are not useable. To the rescue: Sir Digital and his trusty companion, Friar Software. The new technologies allow us remarkable possibilities for eliminating clutter in an image so that the subject of interest stands out as one would like.

You can see air bubbles with a great deal of background debris and light reflection which distract significantly from the insect. Consider the next image.

This is the same image in which the background has been “painted” using computer graphics software. The process is often time-consuming and tedious, requiring meticulous attention to fine detail. However, it will not always be successful and one needs to select one’s image carefully before investing a considerable amount of time on one. Certainly this second image is a major improvement over the first, but it is by no means ideal. There are problems with resolution and pixellation if one tries to increase the size in any large measure but, even more vexing, is the problem of working around the extremely fine details, such as hairs or any type of minute projections around the edges of organisms. Nonetheless, the effort is worthwhile because, in the first image, there is so much distracting clutter that one can only get a vague sense of the insect.

The way in which you process an image depends in large part on the details which you want to present. Consider the following image of a beetle which illustrates not only problems related to the processing of the images, but problems involved in the original image captures. All of the images in this essay were taken with an Olympus SZ III stereo zoom microscope.

As you can see, the magnification is too low and the background clutter is seriously distracting.

A slight shift in the angle of illumination reveals that this critter has some wonderfully metallic green coloration. Here the distraction from the clutter below the specimen is minimal. In this particular piece of amber, there is, in addition to the air bubbles, a problem created by a large number of small reflective disks as seen in the image below.

I have no idea what these disks are, but they create added complications in photographing the insects.

I made an additional attempt to bring the beetle into the fore by painting in a black background.

To my eye, this image is not successful. In this instance, I prefer some of the background color provided by the amber.

In some cases, one may be primarily interested in only a part of an insect and this may simplify dealing with the problem of background.

Here the background is distracting, especially in the lower half of the image. By cropping the image to include only the upper half, the resulting image can be painted fairly readily, since one doesn’t have to deal with the very fine lines of the lower legs. Once the image is painted, it is a very simple matter to change the background as you can see in the two images below.

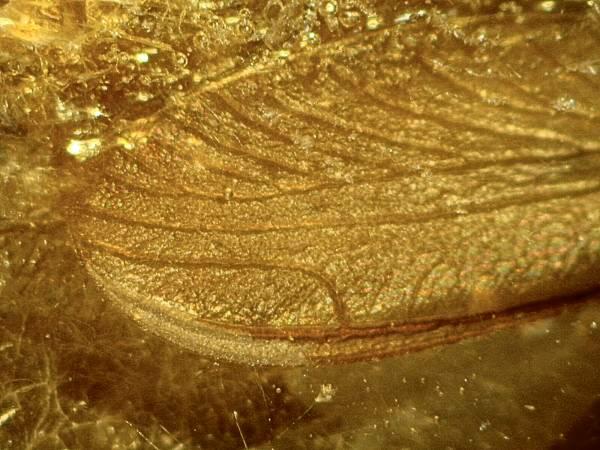

Another object that shows up with some regularity in amber is insect wings.

In this instance the clutter is sufficiently distracting that it is somewhat difficult to make out the definition of the wing.

Here the black background enhances some of the finer detail of the wing.

There are some images which it is simply a waste of time to try to process. Consider the three insect wings in the image below.

Even though I took several images of this grouping, there was very little that could be done to make this group more useful in presenting detail.

This can be especially frustrating when you find a specimen that looks particularly intriguing, but either is positioned in such a way as to make it nearly impossible to focus fully or is surrounded by clutter that obscures a nice, clear view.

This ant or termite is a good example.

However, when you find a really intriguing specimen, don’t give up too easily. The critter below is, as you can see, surrounded by clutter.

However, its bizarre character and my eccentric curiosity drove me to take over a dozen images until I found one that I thought I could work with. I painted the background with a light gray color to increase the contrast and, I must admit, the process was time-consuming, but the result was considerable improvement.

I have no idea what this creature is, but it certainly presents a formidable, perhaps even demonic, appearance.

Occasionally nature takes pity on us poor mortals and gives us glimpses that make being human joyous for a few moments, but who would ever think that a tiny gnat-like creature, millions of years old, preserved in resin could be the source of such a joyous moment?

Here, frozen in time, is a being that looks as though it were making a celebratory leap in some grand cosmic dance.

All comments to the author Richard Howey are welcomed.

Microscopy

UK Front Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor.

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK