CHARLES HENRY VANCE SMITH – MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE

Peter B. Paisley

Sydney, Australia

Charles Henry Vance Smith (“CVS”), was born in 1845 in Macclesfield, Cheshire, the eldest son of the Unitarian clergyman George Vance Smith, and died young, aged 39, in Wales in 1885. His work was admired, and successful, judging by the number of surviving slides, some with optical retail labels. He joined the Postal Micro-Cabinet Club, and probably sold slides through his reputation among members. In 1884, the outgoing president, Alfred Hammond, chose for special mention only a few members from some two hundred who had sent slides, and CVS was one. Less than a year later, CVS was dead.

From the Postal Microscopical Journal. Vol.3 (1884)

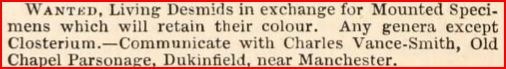

Smith read the botanical work of Julius von Sachs. Another influence was Leopold Dippel, director of famous botanical gardens in Darmstadt-Hesse (Germany) and Professor of Histology at the technical university - Smith translated his work on chlorophyll for the first issue of the Postal Microscopical Journal (1882). The name Dippel (coincidentally or not) has association with German Unitarianism. He also produced a series of slides illustrating Otto Thomé’s 1878 Textbook of Structural and Physiological Botany. CVS had already sought material for mounting outside the postal club, via Science Gossip, and evidently had confidence as a preparer.

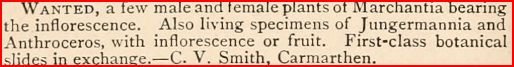

CVS’ advertisement in the Science Gossip exchange column, May 1881.

He was elected to the Quekett Club in July 1879, and several of his slides were exhibited at various club meetings. These mounts were of desmids, fungi, and vegetable cells – to which is added an enigmatic “etc.” - for his exhibits at the special exhibition meeting of April 1881. A selection of botanical slides is shown below.

Some slides, as above, carry small circular stickers referring to descriptions by Otto Thomé. Thomé’s great work of botanical illustration was not published until 1885, after CVS’ death: it was some years in preparation, and CVS may have corresponded with Thomé, his knowledge of German serving him well. That shown below has a reverse side square sticker typical of CVS, and like the circular stickers, refers to Thomé’s shorter book.

A CVS slide, and its sticker from the rear side, underneath the square sticker at the top.

Political and religious controversies

No-one exists divorced from immediate and larger social environments. Dissenters led educational reform, especially in giving “lower orders” scientific knowledge and skill. Unitarian clergy, notably, were activists, their best known example being Joseph Priestley. Andrew Pritchard the optical retailer was in the Newington Green Unitarian congregation (Priestley was once its minister), and may have given lay sermons (his wife chaired organisation of the chapel and its associated parkland). When in London, George Vance Smith probably visited this old established chapel. Mary Wollstonecraft had been a prominent feminist there: her daughter’s Frankenstein had leaned on work, with application to neurology – to the point of resurrection - suggested by experiments of Galvani and others. Later experimental advances by Michael Faraday – another regular visitor to Newington Green Park – added the physiology of “faradism”: higher life itself, dependent on oxygen as researched by Priestley, seemed to some within reach of human production, arousing suspicion of blasphemy among some more orthodox Christians. In Ireland, particularly in Belfast, Unitarians were educational leaders – founding the medical school there. Some were involved in seditious activities, applauding the French Revolution and seeking Irish independence, and were lucky to escape arrest after the failed revolt of Henry Joy McCracken. Hence, Unitarians’ struggle for a place in society was rarely without risk, anywhere in Britain, so they did not lack stamina. Our preparer’s father, George Vance Smith, was such an example.

Natural Theology, a dominant British ideology

One thing allied clergy of every stripe to scientific and political establishments – the idea of an ingenious creator. Science, particularly biology, was enrolled to show design in every plant or animal. This was no parallelism, as in Aquinan or Averroist traditions, between theological and empiricist truth, but an attempt to fuse them – for men like Andrew Pritchard, science was religion. Many clergy agreed, with gusto: the British Association was to no little extent the child of churchmen reacting against the Royal Society, which they saw as decadent, a club of dilettanti gentlemen with amateur fantasies. John Ray – regarded as father of many disciplines – had set the pace for scientific design analysis, and Paley’s later Natural Theology with its watchmaker analogy caught popular imagination (few dared point out that the book plagiarised Ray, and success at Cambridge in particular turned on familiarity with Paley). Editions of Natural Theology, and the Bridgewater Treatises it inspired, multiplied. Even evolution could be grist to the design mill – Robert Chambers’ Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was intended to illustrate divine design, as its (then) anonymous author later made quite explicit. Lord Brougham’s edition of Paley cemented its influence in high political circles, and included a long exegesis of design, Bell’s Animal Mechanics. Microscopy from around 1840 greatly refined observation of new biological worlds: the redoubtable Mrs.Somerville invoked St. Augustine’s aegis – God was great in great things, but greatest in the smallest. Baker had said the microscope revealed “the infinite Power, Wisdom and Goodness of Nature’s Almighty Parent”. Royal patronage was assured, with opticians in an important place – something not lost on the eldest Watson, who seems to have started as “George”, then switching to his second forename William with a change in monarch (another switch by some family member to Victoria might not have amused). Well before that, the most magnificent microscope yet had been made by Adams for the king: Adams’ son, succeeding him as the royal optician, declared that “the application of light” displayed “the energies of the Divine Mind”. That view continued through many editions of Jabez Hogg’s book on the microscope. By the time CVS was making slides, nineteenth century clerical households – dissenting or otherwise – had long since accepted the idea as a given.

George Vance Smith and his family

George was born around 1816 in the Irish midlands, at Portarlington, when his mother was on holiday there. The Vance and Hamilton families had dissenter associations in Ireland, and the names recur in Smith’s family. In Unitarianism, theological quarrels caused internal divisions: such may well have been the case within the Smith family, since both CVS and his brother, George Hamilton Vance Smith, renounced the Smith name for UK censuses, giving the surname “Vance”. George Vance Smith had three sons. CVS was odd man out: his brothers George and Philip were clergymen, but he was a commercial clerk. He is obliterated by an Oxford Dictionary of Biography entry – concocted perhaps by dissenters with strong views – where George Hamilton Vance is erroneously given as the eldest son.

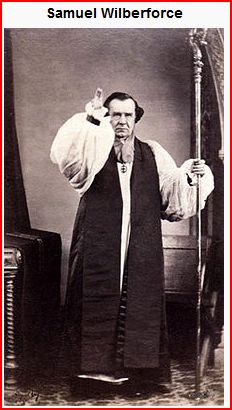

George Smith senior’s father had a joinery business near Newcastle on Tyne, but George went to work in Leeds and received education from Charles Wicksteed, minister of the Mill Hill Unitarian chapel, where Priestley was once the incumbent. The education was intense and successful: in 1836 Smith enrolled in the Manchester Unitarian College (by then moved to York) and while still a divinity student gave tutorials in mathematics. By 1841 the census shows him in a boarding house at 26 Hunter Way, Camden, awaiting graduation from London University’s New College (previously the Hackney College, which was affiliated – later fused - with the Manchester College). Later in 1841, he was ordained as a Unitarian minister at Chapel Lane church in Bradford. Two years after that he moved to a ministry in Macclesfield (not far from Manchester), at King Edward St. chapel: he married Agnes Fletcher in 1843, and our preparer CVS was born there in 1845. By 1846, the Manchester College had shifted from York back to Manchester, and George became its Professor of Theology and Hebrew, to which he later added Syriac, as well as principalship of the college. In 1857, he resigned: the family (now with four children) moved to Germany, and George obtained MA and PhD degrees from the prestigious university divinity faculty at Tubingen. Children readily acquire language, and young CVS’ German fluency later served him well, reading Sachs, Dippel and Thomé. By 1858 the family was back in England, and George succeeded Charles Wellbeloved as minister at St.Savioursgate Chapel in York, remaining until 1875. A near neighbour, Thomas Gough, belonged to the Postal Micro-Cabinet Club, and possibly introduced CVS to it. St.Savioursgate may also have exerted influence. Wellbeloved was a founder of the Yorkshire Philosphical Society and the York Mechanics Insititute, and a founding supporter of the British Association, whose first meeting was at York. Conversations in the Smith household would involve Latin, Greek, Syriac, Hebrew and German authors, but also science, including microscopy – to which the largest contributing societal group were the clergy, via dozens of societies, and journals like Science Gossip. Religious controversy was ever near: in 1870, George Vance Smith was appointed to the international New Testament Revision Company, but was denounced by Bishop “Soapy Sam” Wilberforce (he of the famous British Association exchange with Huxley) as an Arian heretic. CVS could not but notice Wilberforce’s two unsuccessful attempts to have his father removed from the company by decree of the Anglican Convocation: the formidable opponent however dislodged neither George from theology nor CVS from botanising. George was awarded a doctorate in divinity by the University of Jena, and CVS’ botanical slides continued in demand.

“Soapy Sam”- no doubt an imposing figure for CVS

Religious divisions often yielded to microscopy: lay dissenters like Pritchard and muscular Anglican clergy like Charles Kingsley could shelve theology to discuss details of microscopical findings. Dissenters, as previously mentioned, strove to dissolve class barriers to learning: Kenrick said of the York Mechanics Institute, “In common with all institutions for popularising knowledge, it was frowned upon by the higher classes of society in Church and State”. Unitarians were long themselves outsiders from the establishment, and what CVS learned of microscopy was doubtless enhanced by connection with the York Unitarian church, with its connections inherited from Charles Wellbeloved.

Adam’s successors, with God’s most sophisticated research tool

Not for nothing was Linnaeus nicknamed a “second Adam”. The Genesis myth assigned Adam to naming the living world, and accumulated confusion since then was seemingly dissolved by the Linnean scheme, resulting in explosion of taxonomic energy, re-kindled after Banks, Solander and others began bringing specimens from Australia. Enthusiasm for further scientific voyages, like those later led by Wyville Thomson, abounded. New herbariums sprang up like mushrooms. Microscopy boomed, and enlarged and refined an academic industry lampooned by Lewis Carroll as

"………….to describe each particular batch;

Distinguishing those that have feathers and bite and those that have whiskers and scratch."

Arthur Cole, in changing direction from church organist to commercial slide production, experienced no conflict of overall purpose: his familiar punning logo motto, Cole Deum (fear God), declares exactly that. Botanical taxonomy, and its detailed reification on microscope slides, seemed God-ordained activities, and were taken up by CVS (whether out of piety, or in reaction against religion, I have been unable to discover). He tended to eschew “common” names and prefer Linnean formulae. Getting everything correctly classified and in its place was a serious business, witness the proliferation of encyclopaedia editions. But Victorians were perfectly capable of laughing at themselves: The Pirates of Penzance ran for most of 1880 in London, with the “model major-general” delivering his patter song, one of its biggest hits: many amused clergy were among the packed audiences.

Microscopy and geology

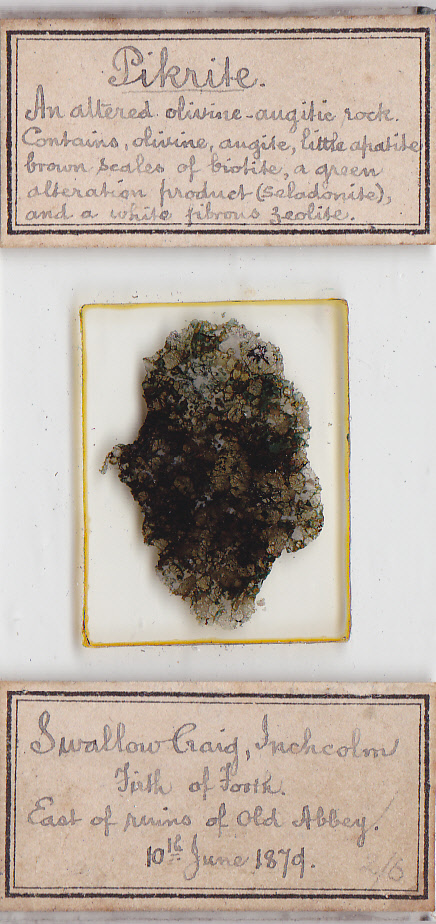

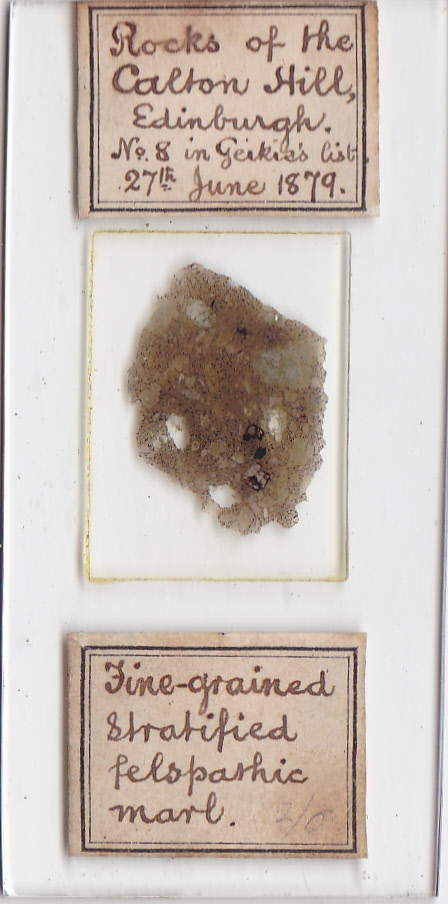

19th century English religion, where geology is concerned, stands in marked contrast to current fanatical fundamentalism. Genesis and geology were reconciled by reading Genesis as metaphor: P.H. Gosse seems alone - an FRS clinging to literal biblical chronology, by intellectual gymnastics which few regarded as sane. Murchison and Sedgwick fell out over religious adherence, not over Silurian geological chronology: Robert Chambers inserted his own chapter on recent geological knowledge, with multi-million year time scales, into his edition of Paley’s Natural Theology. The microscope brought greater accuracy, with increasingly fine rock sections. Fossils were integral to geological strata analysis, and fossil plants or diatoms, for instance, were grist to the mill of microscopical taxonomy. Small wonder that CVS took an interest in geology. Other than the slides shown below, I can find no rock sections by CVS, and other collectors have not heard of any. CVS perhaps envisaged a commercial series: these two, made in 1879, perhaps come from his personal cabinet – the glass is irregular in size and thickness, and annotations are too detailed for any series. They may imply a Scottish visit. The (Archibald) Geikie reference corresponds to lists in a small 1876 book “The Geology of the British Isles”, written to clarify his geological map. These were presumably read by CVS at home, in a college library, or both.

Scottish rock sections by CVS, with precise dates as labelled.

Smith’s first Science Gossip exchange advertisement in 1876: his name here is hyphenated: this may be intentional, or an editorial error.

He did not advertise again until 1881, in the May and June issues of Science Gossip, as shown below.

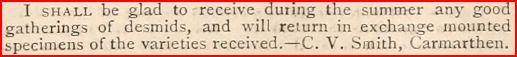

Between these dates – and one would not suspect it from those entries - Smith mounted his Scottish rock material. The entries evoke a preparer confident in technique, with a fairly large output of botanical slides. A further advertisement appeared in Science Gossip in 1882, as below, showing some increase of interests:

The slides shown below reflect this broader scope.

His pursuit of pleurogisma specimens was yielding results, and the starches may hint at a possible wider range of chemical subjects to come. The non-specific exchange offer of “mounted objects” may have included the rhinoceros horn shown here: very atypical subject matter on any conventional view of CVS as botanist, but we have already seen evidence of such divergence in his rock sections.

The travels and tribulations of CVS

The Science Gossip addresses conceal, but relevant census entries reveal, a complex history. Dukinfield was the address of CVS’ brother George, minister at the Unitarian Old Chapel by then. Both brothers had dropped Smith from their names (the journal advertisement did not, presumably for the sake of familiarity to readers.) George junior had returned from a stay in the USA with a divinity degree from Harvard, with its strong “transcendentalist” Unitarian tendency, graduating under the surname Vance. In the 1871 census, CVS was in Macclesfield as “Charles Henry Vance”, aged 25, as a household head, living with his mother in Mary Barber’s lodging house and working as a commercial clerk. Slide preparation on any large scale seems unlikely in a boarding house, hence his brother’s parsonage address, where presumably preparation took place, then or later: CVS probably moved in around 1873. In the 1871 census George senior was still at his church residence of St.Savioursgate chapel in York, at 36 Lord Mayor’s Walk, Bootham, with a housemaid, a cook, and his 25 year old daughter Agnes, now a governess – the youngest son Philip had by then left to pursue a career as a clergyman, and CVS’ mother was also absent. After a brief ministry in Sheffield in 1875, George moved to Wales. By late 1881, as reflected by the Science Gossip entries, CVS and his mother were in Wales, back with George senior, now principal of Carmarthen Presbyterian College, which had split from the Unitarian college there (some Unitarians, as today in Ireland, were “non-subscribing Presbyterians”). Meantime, the youngest brother, Philip, was now also ordained, and minister of the Hindley Unitarian church near Wigan – calling himself “Vancesmith”. Perhaps CVS was now reconciled with his father’s comparatively non hard line Unitarianism – at any rate he resumed his Smith surname for the census. Earlier in 1881 however the census shows that CVS and his mother were not in Carmarthen, but in Bilton, a Harrogate suburb, and they had probably been there for a considerable period.

Ill-starred children?

Between leaving Dukinfield (part of Greater Manchester) and reaching Wales, CVS abandoned occupation as a commercial clerk, and the 1881 census describes him as of “no occupation”. As far as microscopy was concerned, he was far from unoccupied, since both Science Gossip and the Postal Microscopical Society yield ample evidence of widening interests and activity, as does evidence from CVS slides. A catalogue of botanical slides was issued around this time (see Bracegirdle’s entry on CVS). Ergo, “no occupation” should be read as “with no full time salaried job”. Why? It’s possible Carmarthen offered no openings for a clerk, or if it did, CVS had not yet found such work, having returned from Harrogate only a few weeks before the census. More probably, full time occupation as a slide preparer was intended. But CVS must have been ill – he died young aged 39, in 1885, before his microscopy career could blossom fully.

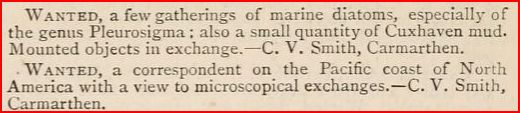

The Smith family did not lack longevity genes: Agnes survived until nearly eighty, and George lived longer, with sufficient energy to re-marry a wife some thirty years his junior in 1894, and did not die until 1902. George junior also lived to a ripe old age, and died in 1939. The two other sons, Charles and Philip, and the daughter Agnes, did not fare so well. All three died in early middle age. Philip died in Cannes in 1895 aged around 40: I have been unable to trace his precise date of death, which was reported in Wigan on January 14, nor his cause of death, but his move to the south of France from Hindley, Wigan (where he was the Unitarian minister) suggests that his state of health was thought to require a more salutary climate – a common recourse in chronic conditions, for those who could afford it. Sea baths at Cannes had been praised in the British Medical Journal in 1888 (Oct.27, pp. 931-2), and in various other articles since that.

From the Wigan almanac 1895

Early in the nineteenth century, the village of Lees produced bottled water of medicinal repute, and had ambitions to become a spa centre, as “the Lancashire Harrogate”. By CVS’ time it had been swallowed up by Manchester, its spa endeavour well nigh obliterated by the expanding cotton industry. The bottled water still existed though, and may have attracted CVS as a therapeutic agent obtainable at Dukinfield. In 1881, by contrast, the Harrogate suburb of Bilton offered a newly booming spa, not only with renowned water to drink, but also with lavish baths and all their associated paraphernalia. Around the same time, there was renewed emphasis on hydropathy for chronic diseases (many of which of course physicians could do little to help by “mainstream” therapy). Often, prestigious physicians co-operated with entrepreneurs who ran the facilities, some of which sported Byzantine grandeur. John Smedley, one such financier with premises in Derbyshire and elsewhere, oscillates between quoting testimonials from co-operative doctors and denigrating the methods of their sceptical colleagues: much is made in his book of his treatments’ worth for chronic conditions such as tuberculosis and neurological or psychiatric disorders, all whose aetiology remained obscure at the time.

“Healthy air” was another favoured general therapy, and if CVS got his Scottish rock material in person, the supposedly fresher northern air may have been a reason for the visit. Certainly, gentle hydrotherapy could alleviate conditions like arthritis, and as a “rest cure”, it could do little harm in other chronic conditions.

There seems little doubt that hydrotherapy was the major reason for CVS’ stay in Bilton. George Vance Smith’s predecessor as minister at St.Savioursgate, Charles Wellbeloved, had undergone prologed hydrotherapy, and put great faith in its efficacy. Alas, CVS died less than four years after his Bilton sojourn, with his slide preparing enterprise cut short. In 1888, George senior resigned from the Carmarthen College – and also from his ministry at the Parc-y-Felfed chapel - and moved to Bath with his wife Agnes and daughter, also Agnes. The move was, in all probability, again, “for the waters”. His daughter died in 1891, and his wife in 1893. George moved back north to Bowdon, Manchester, and acquired a new spouse, Elizabeth Todd (and yet another cook and housemaid.)

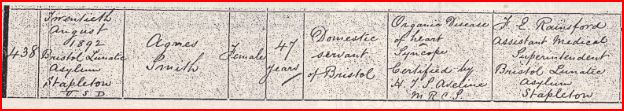

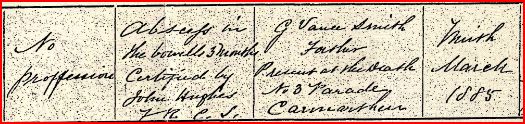

It may be that the three siblings all died young from separate conditions. But if some underlying common cause was involved, genetic aetiology is an obvious possibility. Agnes junior’s death certificate may contain a vital clue. Previously a governess, she was ominously described (presumably by George senior) as “of no occupation”, for the 1891 census. The same had been true ten years earlier for CVS. Depending on one’s attitude, a governess might be described as a domestic servant, but the entry below may well indicate some deterioration in Agnes’ capabilities, and the census entry suggests any work was impossible by 1891.

Agnes junior’s death certificate

One condition springs to mind which caused mysterious symptoms well before early death, often also brought embarrassment and shame to families, and usually involved fatal secondary disease: Huntington’s chorea. The place of Agnes junior’s death, rather than the stated cause, seems significant – the Stapleton lunatic asylum in Bristol. The waters of Bath had been of no avail. As often as not, mental asylums were the final abodes of sufferers from Huntington’s chorea. The insidious dementia involved was cruel to its victims, as was the interruption of ordinary activities by neuromuscular dysfunction. The Irish midlands, whence came CVS’ mother, is a well known focus of the mutation, and she may have carried the gene. Philip’s early exit from his Unitarian ministry may be suggestive: inappropriate eccentricity would be obvious to a Wigan congregation, but scarcely noticeable among the expatriate population of Cannes. Non-fatal in itself, Huntington’s disease is generally associated with other serious conditions: respiratory and cardiac pathology are at the top of the list, and gastrointestinal disease is also not infrequent. Death came quicker, from secondary disease, in an era lacking today’s antibiotics and range of cardiac treatments. Children of carriers have a 50-50 chance of succumbing to Huntington’s disease, and the Smith family fits the picture, with the lucky son George surviving into old age. In the absence of clinical records from doctors who attended the family, the possibility of Huntington’s disease must remain speculative – but if one had to describe a hypothetical family which fits the pattern, this could be it.

Whither CVS?

I have been unable to find evidence of microscopical activity by George Vance Smith, although as a clergyman it is virtually inevitable he took an interest in microscopical findings. Without family records such as diaries or correspondence, one cannot tell what theological differences may have existed within the family, and how these may have affected CVS. The CVS logo may be suggestive in this respect. As the odd brother out, CVS may have been regarded as a maverick in preferring commercial slide mounting to a career as a clergyman. It is certainly odd that his father, who was present at CVS’ death, stated for the certificate (below) that CVS had “no profession”. Mounting specimens, it seems, may have been considered unworthy of mention.

Without any evidence, I likewise cannot tell what discussions or disputes affected the Smith family regarding evolutionary theory, but it seems probable they occurred, perhaps reinforced by CVS’ involvement in taxonomy.

Vance or Smith? The lack of any dot after the logo’s S may indicate ambivalence. As in his Science Gossip advertisement, CVS may sometimes have hyphenated his name; he and his brother George dropped “Smith” and became “Vance”; and the youngest son Philip appears on record as minister of the Hindley Unitarian church as “Vancesmith”.

One can only speculate on where CVS’ mounting career might have led had he not died young. It is sure that it included more than botany, as evidence already shown indicates. The slides illustrated below may betoken series already begun, and one cannot but think there would have been more variety in this preparer’s output than his “standard botanical” work suggests. As old collections are dispersed, fresh evidence of his output may come to light.

More CVS variety: various series may have been planned, or already begun.

“Professional mounter of botanical material” is a usual description for Charles Henry Vance Smith. In CVS’ full context however, there is rather more to him than may hitherto have met the eye.

Comments to the author will be welcomed.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cliff Hobden of the NSW Police forensic handwriting section for authentication of the rhinoceros horn label writing, to Professor David Oldroyd for discussions regarding “Geikie’s list”, to Peter Hodds for locating the CVS slide with the reference to Thomé on CVS’ square label, to Brian Stevenson for sorting out some confusion with the GRO (UK), and to Rev. Alex Bradley (Principal, Manchester College, UK) for information on Philip Vancesmith.

Sources

www.ancestry.com

Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

William Paley, Natural Theology – umpteen editions, particularly those of Robert Chambers, and Lord Brougham/ Charles Bell

Hardwicke’s Science Gossip

Journal of the Postal Microscopical Society

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

John Kenrick (1860) Life of Charles Wellbeloved

Bracegirdle’s Microscopical Mounts and Mounters (1998)

Smedley’s Practical Hydropathy (17th edition, 1872)

Robert Chambers - Explanations – a Sequel (1845). Like the Vestiges, published anonymously.

(a work little quoted, but making natural theology intentions clear regarding the Vestiges.)

UK General Register Office

Quekett Club Journal

P.H. Gosse, Omphalos (1849)

John Ray, The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Creation (1691)

Wigan yearbook extracts for 1889, 1895 via www.wiganworld.com

British Medical Journal, October 1888

Microscopy UK Front

Page

Micscape

Magazine

Article

Library

Published in the September 2010 edition of Micscape Magazine.

Please report any Web problems or offer general comments to the Micscape Editor .

Micscape is the on-line monthly magazine of the Microscopy UK website at Microscopy-UK .

© Onview.net Ltd, Microscopy-UK, and all contributors 1995 onwards. All rights reserved. Main site is at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk .